The Variable

advertisement

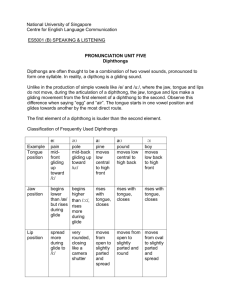

Background The Variable a) Yod-dropping (Carey 2009) Yod-dropping is a term used to describe the deletion of the first element of the sequence /ju/ in words such as tune thus [tjun] becomes [tu:n]. It is a salient dialect feature when it occurs as it is easily recognisable. In the case of the Norfolk dialect, it has become iconic due to the most part to the advertisement for Bernard Matthews Turkey products and the word “bootiful” (Amos, Britain and Spurling 2008) b) Yod-coalescence Yod-coalescence occurs when the [j] from the sequence /ju/ palatalises and coalesces with the preceding consonant to become an affricate e.g. tune [tjun] becomes [ʧun] or duke [djuk] becomes [ʤuk], if the preceding consonant is alveolar (Britain and Johnson 2009). Trudgill (1984:59) states that after /t/ or /d/, “yodcoalescence is in competition with yod-dropping” and is “more widespread” than its yod-dropping counterpart in England. c) The Phonological Perspective (Carey 2009) /j/ is the first segment of the sequence of the variable /ju/ and is a coronal glide. Although it has characteristics associated with high vowels e.g. [i] it cannot be viewed as a true vowel as it cannot bear mora and in the onset position (without its companion [u]) will pattern like a consonant and may be followed by any vowel. However if /j/ is preceded by a consonant then the nucleic vowel must be [u], producing the /ju/ sequence. There is an ongoing debate amongst phonological theorists as to the exact nature of /ju/, in that some view it as a diphthong, others as a CV sequence and some as a unique entity which can affiliate to either camp. Briefly then here is a selection of the some arguments for /ju/ as a diphthong and conversely for /j/ being split from the /u/ and positioned in the onset: i) Violation of Onset Constraints Amos (2007: 21) notes that /ju/ can follow coronals such as in lewd [ljud] and nude [njud]. This would make it unacceptable in the onset position as it violates both MSD and OCP and thus it must take the nucleic position as a diphthong. However the constraint of binarity provides an argument against the diphthong status of /ju/. /j/ does not occur after a branching onset (apart from after /s/ e.g. in slew but this will be disregarded due to the “specialness” of /s/) so although lewd is acceptable, blue *[blju] is not because of the binarity constraint. This indicates that the /j/ from the sequence will position in the onset as it complies with the binarity ruling. However it does appear that some speakers do produce a [blju] – like word, particularly in ultra RP or where they are hypercorrecting1 (Britain and Johnson 2009). ii) Lexical Derivations 1 Hypercorrection is a term used to describe a phenomenon whereby speakers over-use a particular feature in order to converge to a speech form that is viewed as carrying more prestige (Romaine 2000:75) In some lexical derivations, vowel shortening occurs in Class 1 morphemes e.g. deprive ~ deprivation (diphthong [аɪ] to monophthong [ɪ]). As this shortening also occurs in the pair produce ~ production where /ju/ is shortened to [ʌ]. This supports the view that the /ju/ sequence is in fact a diphthong as in this context its behaviour patterns as diphthong (Britain and Johnson 2009). iv) Re-syllabification Borrowsky (1984 and 1986) considers the/ju/ sequence as evolving from a complex /iu/ unit. However she is referring only to cases where the preceding consonant is a coronal, as in Gen Am (General American). In the East Anglian dialect the deletion of the /j/ can occur in all post consonantal environments (see Section 2.1 d). Borrowsky describes the process thus; at the point of syllabification /iu/ splits as illustrated below: Fig i) Diagram of Borrowsky’s Re-syllabification i split from u 1. takes onset position as/ j/ takes nucleus position or 2. becomes deleted if blocked by an onset constraint She goes on to say that in the case of polysyllabic words in a Ci sequence, the (coronal) C will be re-syllabified to the coda of the preceding syllable. Amos (2007:21) illustrates this using value, which is initially syllabified as /væ.liu/. Then after the detachment of /i/ /l/ re-syllabifies to the coda of the first syllable and /i/ reemerges as /j/ producing /væl.ju/. Thus /j/ is in the onset position and the first syllable will gain bimoracity through the filling of the coda position and be capable of stress bearing. v) Article Selection When examining article selection, it is the usual rule that nouns stating with a vowel will select the definite article pronunciation [ði] e.g. the apple as opposed to those nouns starting with a consonant which select [ðə] e.g. the cat. Similarly with the indefinite article a versus an. Nouns such as ewe /ju/, select the consonantal articles that is the [ðə] ewe and a ewe, thus the word initial /j/ is treated as a consonant and will take onset position (Britain and Johnson 2009). d) History of Yod-dropping and Geographical Distribution (Carey 2009) Wells (1982:206-208) describes the historical development of yod-dropping in three stages: i) Early yod-dropping [ju] developed from the rising diphthong [ɪŭ] in the mid to late 17th century. In certain environments, palatals, /r/ and C+/l/ the /j/ was lost e.g. chew [ʧju] became [ʧu:] and so on. However certain varieties of English including Welsh, some Northern dialects and some varieties of American English retained the original [ɪŭ] and thus do not yod-drop. ii) Later yod-dropping /j/ was dropped after coronals but retained after labials and velars. This may explain the prevalence of yod-dropping in London English (Cockney) after nasal coronals e.g. news [nu:z] (Trudgill 1999:58-61). iii) Generalised yod-dropping Loss of /j/ can occur in all post consonantal environments. It would seem from Wells’ theory that East Anglia then has moved furthest along the yod-dropping continuum to the “Generalised” stage, as in many parts of this region, dialectal varieties demonstrate this pattern. This would make East Anglia the innovator of the yod-dropping feature. However there may be another explanation as at around the time the [ɪŭ] was developing to [ju] the region saw an influx of Dutch and French migrants. There is a view then that due to reasons of ease of acquisition, [ɪŭ] was simplified to the monophthong [u] (Britain and Johnson 2009). e) History of Yod coalescence and Geographical Distribution As previously mentioned Trudgill (1984:59) considers yod coalescence to be “widespread” throughout England. Wells (1982) when referring to London speech, says that although yod-dropping still features in working class speech post /n/, the palatalised form following /t/ and /d/ is now more common than /j/ deletion after these consonants.