Utilitarianism Background

advertisement

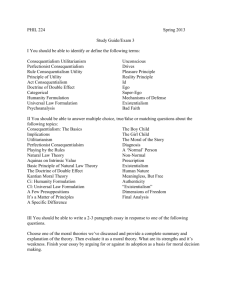

ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS Applied Ethics 1. How can we define “good” actions? What is the good life? How do human beings actually think about and make moral decisions? 2. How can short pieces of literature -- through narrative structure (flashback, pacing, frames), plot (exposition, conflict, rising action, resolution), imagery, narrative point of view, metaphor, characterization, setting, irony – suggest, describe, exemplify, and/or add complexity to ethical dilemmas? ESSENTIAL SKILLS 1. Paraphrasing 2. Analysis 3. Use of literary elements in writing 4. Transitions and Recursivity 5. Comparison and Connection Utilitarianism The Pursuit of Happiness 18th century – David Hume Classical utilitarianism's two most influential contributors are Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill. Bentham, who takes happiness as the measure for utility, says, "it is the greatest happiness of the greatest number that is the measure of right and wrong".[1] Foundational Utilitarianism The moral quality of action should be judged by its consequences on human happiness – the sum of pleasures and pains. We should aim at the ‘greatest happiness for the greatest number’. Ethics should be studied rationally, like a science. When making a decision the happiness of all people must be considered, not just the individual directly making the decision. Moral decision-making involves adding up the likely pleasure and pain that will likely be a consequence of the action. The fancy term for this is consequentialism. It is possible that the exact same action – say, killing a man – can be moral in one instance – shooting an unarmed Hitler in 1939 – because it overall increases the pleasure and minimizes the pain of the most number of people and immoral in another instance – shooting an unarmed pedestrian. Bethem proposed something called Hedonic Calculus – to consider how ultimately pleasurable an action is, and thus how moral, Benthem proposed we work our way through this formula. Benthem even came up with a new word for the goal – something “felicific” brings the greatest happiness to the greatest number. Here’s are two examples of this: Action # 1: eating a Scapp’s Chicken Parm sandwich for lunch Intensity – how strong is the pleasure? reasonably pleasurable Duration – how long will the pleasure last? the way I eat, five minutes Certainty – how certain is it that pleasure will result from the action? those sandwiches are pretty good, but sometimes I eat too fast and get hearburn. Propinquity – how soon will the pleasure occur? Immediate Fecundity – How probable is it that the action will be followed by more pleasure, for you and for others? Very slim. Once it is gone, I’m left with nothing. Purity – How free from pain is the action, for you and for others This is pretty benign – I guess it causes pain to the chicken killed and maybe to the wage -workers who process the chicken. Extent – How many people will be impacted by this action? Me and the Scapp’s family, the chickens, and the workers (although minimally – if I stopped eating the sandwich, it would probably make no difference) RESULT This action is basically felicific and thus reasonably moral. Action # 2: State’s decision to execute a murderer. Action # 3: Decision to save the baby’s life. Utilitarianism The Pursuit of Happiness (note sheet) Foundational Utilitarianism Major Figures and Time Period = Moral Action = How should morality be assessed? Consequentialism = Are any actions universally good? Hedonic Calculus = Applied Ethics ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS 1. How can we define “good” actions? What is the good life? How do human beings actually think about and make moral decisions? 2. How can short films -- through narrative structure, point of view, titling, characterization, plot (exposition, conflict, rising action, resolution), setting, atmosphere, soundtrack, cinematography (movement, framing, focus, color, composition) -- suggest, describe, exemplify, and/or add complexity to complex ethical dilemmas? 3. How can short pieces of literature -- through narrative structure (flashback, pacing, frames), plot (exposition, conflict, rising action, resolution), imagery, narrative point of view, metaphor, characterization, setting, irony – suggest, describe, exemplify, and/or add complexity to ethical dilemmas? ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS Applied Ethics 1. How can we define “good” actions? What is the good life? How do human beings actually think about and make moral decisions? 2. How can short films -- through narrative structure, point of view, titling, characterization, plot (exposition, conflict, rising action, resolution), setting, atmosphere, soundtrack, cinematography (movement, framing, focus, color, composition) -- suggest, describe, exemplify, and/or add complexity to complex ethical dilemmas? 3. How can short pieces of literature -- through narrative structure (flashback, pacing, frames), plot (exposition, conflict, rising action, resolution), imagery, narrative point of view, metaphor, characterization, setting, irony – suggest, describe, exemplify, and/or add complexity to ethical dilemmas? ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS Applied Ethics 3. How can we define “good” actions? What is the good life? How do human beings actually think about and make moral decisions? 4. How can short pieces of literature -- through narrative structure (flashback, pacing, frames), plot (exposition, conflict, rising action, resolution), imagery, narrative point of view, metaphor, characterization, setting, irony – suggest, describe, exemplify, and/or add complexity to ethical dilemmas? Utilitarianism The Pursuit of Happiness Foundational Utilitarianism The moral quality of action should be judged by its consequences on human happiness – the sum of pleasures and pains. We should aim at the ‘greatest happiness for the greatest number’. Ethics should be studied rationally, like a science. When making a decision the happiness of all people must be considered, not just the individual directly making the decision. Moral decision-making involves adding up the likely pleasure and pain that will likely be a consequence of the action. The fancy term for this is consequentialism. It is possible that the exact same action – say, killing a man – can be moral in one instance – shooting an unarmed Hitler in 1939 – because it overall increases the pleasure and minimizes the pain of the most number of people and immoral in another instance – shooting an unarmed pedestrian. Bethem proposed something called Hedonic Calculus – to consider how ultimately pleasurable an action is, and thus how moral, Benthem proposed we work our way through this formula. Benthem even came up with a new word for the goal – something “felicific” brings the greatest happiness to the greatest number. Here’s are two examples of this: Action # 1: eating a Scapp’s Chicken Parm sandwich for lunch Intensity – how strong is the pleasure? reasonably pleasurable Duration – how long will the pleasure last? the way I eat, five minutes Certainty – how certain is it that pleasure will result from the action? those sandwiches are pretty good, but sometimes I eat too fast and get hearburn. Propinquity – how soon will the pleasure occur? Immediate Fecundity – How probable is it that the action will be followed by more pleasure, for you and for others? Very slim. Once it is gone, I’m left with nothing. Purity – How free from pain is the action, for you and for others This is pretty benign – I guess it causes pain to the chicken killed and maybe to the wage -workers who process the chicken. Extent – How many people will be impacted by this action? Me and the Scapp’s family, the chickens, and the workers (although minimally – if I stopped eating the sandwich, it would probably make no difference) RESULT This action is basically felicific and thus reasonably moral. Action # 2: State’s decision to execute a murderer. Action # 3: Decision to save the baby’s life. Utilitarianism The Pursuit of Happiness (note sheet) Foundational Utilitarianism Major Figures and Time Period = Moral Action = How should morality be assessed? Consequentialism = Are any actions universally good? Hedonic Calculus =