Module Guide Template

advertisement

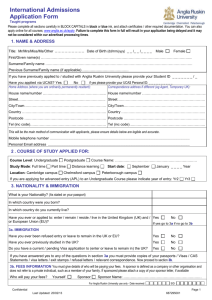

Faculty of Arts’ Law and Social Sciences Writing for Images Department: Cambridge School of Art Module Code: MOD000157 Academic Year: 2012/13 Semester 2 1 Contents Writing for Images 1 1. Key Information 2 2. Introduction to the Module 2 3. Intended Learning Outcomes 3 4. Outline Delivery 3 4.1 Attendance Requirements 3 5. Assessment 4 6. How is My Work Marked? 5 7. Assessment Criteria and Marking Standards 7 8. Assessment Offences 8 9. Learning Resources 10 9.1. Library 10 9.2. Other Resources 12 10. Module Evaluation 12 11. Module anthology . 13 1 1. Key Information Module/Unit title: Writing for Images Module Leader: Mick Gowar Ruskin 128, Cambridge School of Art. Extension: 2741 Email: mick.gowar@anglia.ac.uk Module Tutors: John Clarke Every module has a Module Definition Form (MDF) which is the officially validated record of the module. You can access the MDF for this module in three ways via: the Virtual Learning Environment (VLE) the My.Anglia Module Catalogue at www.anglia.ac.uk/modulecatalogue Anglia Ruskin’s module search engine facility at www.anglia.ac.uk/modules All modules delivered by Anglia Ruskin University at its main campuses in the UK and at Associate Colleges throughout the UK and overseas are governed by the Academic Regulations. You can view these at www.anglia.ac.uk/academicregs. A printed extract of the Academic Regulations, known as the Assessment Regulations, is available for every student from your Faculty Office (all new students will have received a copy as part of their welcome pack). In the unlikely event of any discrepancy between the Academic Regulations and any other publication, including this module guide, the Academic Regulations, as the definitive document, take precedence over all other publications and will be applied in all cases. 2. Introduction to the Module Writing for Images enables you to explore the relationships between texts and images through your own creative practice. In the contemporary world of art and design, the practitioner is often called upon to accompany images with texts, written in a variety of voices. The module is specifically designed to prepare you for these professional expectations and is intended to inform and complement your work in studio specialisms, such as illustration, photographic and digital media, video, animation and fine art. The process of writing for images is addressed in a series of seminars and writing workshops led by a professional author. Assessment centres on a project combining text and image and a selection from the pieces of written work produced during the module. You should note that this is a module intended to develop skills in creative writing, and is not a study skills module to improve basic written and spoken English. 2 3. Intended Learning Outcomes Anglia Ruskin modules are taught on the basis of intended learning outcomes and on successful completion of the module, students will be expected to be able: 1. Demonstrate a critical understanding of the creative and professional processes associated with writing for images 2. Display an ability to write texts in a variety of styles and types to accompany illustrations, prints, moving images and photographs 3. Communicate clearly and appropriately, in writing, demonstrating a sense of audience 4. Demonstrate critical self-awareness, situating their own practice within professional and critical contexts 4. Outline Delivery A weekly series of practical, two-hour writing workshops. Over the course of the semester students will build up a portfolio of a variety of different types of writing which might include: Short verse forms – senryu, haiku, triolet etc Short fiction written in response to photographs and still images Writing for children – fiction and non-fiction Short pieces arising from writing games and techniques – for example cut-ups, and the surrealist game‘The Exquisite Corpse’ etc. This portfolio will form the basis for selecting work for assessment: one piece to be developed into a visual project combining text and images, which might consist of a dummy for a children’s picture book with a sample spread; a short film or animation, or a storyboard and script; detailed plans for an installation or performance; a 3-D work; a piece of packaging or promotional/advertising material; a selection of photographs with accompanying texts etc. a selection of two other pieces written during the course Students will have the opportunity to read their work and receive feedback during many of the sessions. Students will also be introduced to the work of a number of leading modern authors and poets, pioneering animators and musicians involved in music theatre and performance and video art, such as Luciano Berio, Harrison Birtwistle and Steve Reich. 4.1 Attendance Requirements Attending all your classes is very important and one of the best ways to help you succeed in this module. In accordance with the Student Charter, you are expected to arrive on time and take an active part in all your timetabled classes. If you are unable to attend a class for a valid reason (eg: illness), please contact your Module Tutor. Anglia Ruskin will closely monitor the attendance of all students and will contact you by e-mail if you have been absent without notice for two weeks. Continued absence can result in various consequences including the termination of your registration as you will be considered to have withdrawn from your studies. International students who are non-EEA nationals and in possession of entry clearance/leave to remain as a student (student visa) are required to be in regular attendance at Anglia Ruskin. Failure to do so is considered to be a breach of national immigration regulations. Anglia Ruskin, like all British Universities, is statutorily obliged to inform the UK Border Agency of the Home Office of significant unauthorised absences by any student visa holders. 3 5. Assessment Assessment will be in two elements, as outlined above: 70% of the marks will be for a visual project: one piece to be developed into a visual project combining text and images, which might consist of a dummy for a children’s picture book with a sample spread; a short film or animation, or a storyboard and script; detailed plans for an installation or performance; a 3D work; a piece of packaging or promotional/advertising material; a selection of photographs with accompanying texts etc. Your visual project must also be accompanied by a 1,000 word statement briefly explaining how you developed your project, what creative decisions you made and why you made the choices you did. 30% of the marks will be for a text portfolio: a selection of two other pieces written during the course All coursework assignments and other forms of assessment must be submitted by the published deadline which is detailed above. It is your responsibility to know when work is due to be submitted – ignorance of the deadline date will not be accepted as a reason for late or non-submission. All student work which contributes to the eventual outcome of the module (ie: if it determines whether you will pass or fail the module and counts towards the mark you achieve for the module) is submitted to the designated room using the formal submission sheet. Academic staff CANNOT accept work directly from you. If you decide to submit your work to the Departmental office by post, it must arrive by midday on the due date. If you elect to post your work, you do so at your own risk and you must ensure that sufficient time is provided for your work to arrive at the Departmental office. Posting your work the day before a deadline, albeit by first class post, is extremely risky and not advised. Any late work (submitted in person or by post) will NOT be accepted and a mark of zero will be awarded for the assessment task in question. You are requested to keep a copy of your work. All coursework assignments and other forms of assessment must be submitted by the published deadline which is detailed above. It is your responsibility to know when work is due to be submitted – ignorance of the deadline date will not be accepted as a reason for late or non-submission. Your work will be handed in on the same day as your studio modules: Wednesday May 15. You will be given notice of the room to which you should hand your work. Academic staff CANNOT accept work directly from you. Any late work (submitted in person or by post) will NOT be accepted and a mark of zero will be awarded for the assessment task in question. You are requested to keep a copy of your work. Feedback You are entitled to feedback on your performance for all your assessed work. For all assessment tasks which are not examinations, this is provided by a member of academic staff completing the assignment coversheet on which your mark and feedback will relate to the achievement of the module’s intended learning outcomes and the assessment criteria you were given for the task when it was first issued. Examination scripts are retained by Anglia Ruskin and are not returned to students. However, you are entitled to feedback on your performance in an examination and may request a meeting with the Module Leader or Tutor to see your examination script and to discuss your performance. 4 Anglia Ruskin is committed to providing you with feedback on all assessed work within 20 working days of the submission deadline or the date of an examination. This is extended to 30 days for feedback for a Major Project module (please note that working days excludes those days when Anglia Ruskin University is officially closed; eg: between Christmas and New Year). Personal tutors will offer to read feedback from several modules and help you to address any common themes that may be emerging. At the main Anglia Ruskin University campuses, each Faculty will publish details of the arrangement for the return of your assessed work (eg: a marked essay or case study etc.). Any work which is not collected by you from the Faculty within this timeframe is returned to the iCentres from where you can subsequently collect it. The iCentres retain student work for a specified period prior to its disposal. On occasion, you will receive feedback and marks for pieces of work that you completed in the earlier stages of the module. We provide you with this feedback as part of the learning experience and to help you prepare for other assessment tasks that you have still to complete. It is important to note that, in these cases, the marks for these pieces of work are unconfirmed. This means that, potentially, marks can change, in either direction! Marks for modules and individual pieces of work become confirmed on the Dates for the Official Publication of Results which can be checked at www.anglia.ac.uk/results. 6. How is My Work Marked? After you have handed your work in or you have completed an examination, Anglia Ruskin undertakes a series of activities to assure that our marking processes are comparable with those employed at other universities in the UK and that your work has been marked fairly and honestly. These include: Anonymous marking – your name is not attached to your work so, at the point of marking, the lecturer does not know whose work he/she is considering. When you undertake an assessment task where your identity is known (eg: a presentation or Major Project), it is marked by more than one lecturer (known as double marking) Internal moderation – a sample of all work for each assessment task in each module is moderated by other Anglia Ruskin staff to check the marking standards and consistency of the marking External moderation – a sample of student work for all modules is moderated by external examiners – experienced academic staff from other universities (and sometimes practitioners who represent relevant professions) - who scrutinise your work and provide Anglia Ruskin academic staff with feedback, advice and assurance that the marking of your work is comparable to that in other UK universities. Many of Anglia Ruskin’s staff act as external examiners at other universities. Departmental Assessment Panel (DAP) – performance by all students on all modules is discussed and approved at the appropriate DAPs which are attended by all relevant Module Leaders and external examiners. Anglia Ruskin has over 25 DAPs to cover all the different subjects we teach. This module falls within the remit of the Cambridge School of Art DAP. The following external examiners are appointed to this DAP and will oversee the assessment of this and other modules within the DAP’s remit: External Examiner’s Name Academic Institution Position or Employer Norwich University College of Supervisor, Graduate Studies Arts The above list is correct at the time of publication. However, external examiners are appointed at various points throughout the year. An up-to-date list of external examiners is available to internal browsers only at www.anglia.ac.uk/eeinfo. Dr. George Maclennan 5 Student submits work / sits examination Work collated and passed to Module Leader Work is marked by Module Leader and Module Tutor(s)1. All marks collated by Module Leader for ALL locations2 Internal moderation samples selected. Moderation undertaken by a second academic3 Any issues? YES NO Students receive initial (unconfirmed) feedback External Moderation Stage Internal Moderation Stage Marking Stage Flowchart of Anglia Ruskin’s Marking Processes Unconfirmed marks and feedback to students within 20 working days (30 working days for Major Projects) External moderation samples selected and moderated by External Examiners4 Any issues? YES NO DAP4 Stage Marks submitted to DAP5 for consideration and approval 1 2 3 4 5 Confirmed marks issued to students via e-Vision Marks Approved by DAP5 and forwarded to Awards Board All work is marked anonymously or double marked where identity of the student is known (eg: in a presentation) The internal (and external) moderation process compares work from all locations where the module is delivered (eg: Cambridge, Chelmsford, Peterborough, Malaysia, India, Trinidad etc.) The sample for the internal moderation process comprises a minimum of eight pieces of work or 10% (whichever is the greater) for each marker and covers the full range of marks Only modules at levels 5, 6 and 7 are subject to external moderation (unless required for separate reasons). The sample for the external moderation process comprises a minimum of eight pieces of work or 10% (whichever is the greater) for the entire module and covers the full range of marks DAP: Departmental Assessment Panel – Anglia Ruskin has over 25 different DAPs to reflect our subject coverage 6 1. Assessment Criteria and Marking Standards LEVEL 5 (was level 2) Level 5 reflects continuing development from Level 4. At this level students are not fully autonomous but are able to take responsibility for their own learning with some direction. Students are expected to locate an increasingly detailed theoretical knowledge of the discipline within a more general intellectual context, and to demonstrate this through forms of expression which go beyond the merely descriptive or imitative. Students are expected to demonstrate analytical competence in terms both of problem identification and resolution, and to develop their skill sets as required. Generic Learning Outcomes (GLOs) (Academic Regulations, Section 2) Mark Bands Outcome Characteristics of Student Achievement by Marking Band Knowledge & Understanding 90-100% Exceptional information base exploring and analysing the discipline, its theory and ethical issues with extraordinary originality and autonomy. 80-89% Outstanding information base exploring and analysing the discipline, its theory and ethical issues with clear originality and autonomy 70-79% Achieves module outcome(s) related to GLO at this level Excellent knowledge base, exploring and analysing the discipline, its theory and ethical issues with considerable originality and autonomy Intellectual (thinking), Practical, Affective and Transferable Skills Exceptional management of learning resources, with a higher degree of autonomy/ exploration that clearly exceeds the brief. Exceptional structure/accurate expression. Demonstrates intellectual originality and imagination. Exceptional team/practical/professional skills. Outstanding management of learning resources, with a degree of autonomy/exploration that clearly exceeds the brief. An exemplar of structured/accurate expression. Demonstrates intellectual originality and imagination. Outstanding team/practical/professional skills Excellent management of learning resources, with a degree of autonomy/exploration that may exceed the brief. Structured/accurate expression. Very good academic/ intellectual skills and team/practical/professional skills 60-69% Good knowledge base; explores and analyses the discipline, its theory and ethical issues with some originality, detail and autonomy Good management of learning with consistent selfdirection. Structured and mainly accurate expression. Good academic/intellectual skills and team/practical/ professional skills 50-59% Satisfactory knowledge base that begins to explore and analyse the theory and ethical issues of the discipline Satisfactory use of learning resources. Acceptable structure/accuracy in expression. Acceptable level of academic/intellectual skills, going beyond description at times. Satisfactory team/practical/professional skills. Inconsistent self-direction Basic knowledge base with some omissions and/or lack of theory of discipline and its ethical dimension Basic use of learning resources with little self-direction. Some input to team work. Some difficulties with academic/ intellectual skills. Largely imitative and descriptive. Some difficulty with structure and accuracy in expression, but developing practical/professional skills Limited knowledge base; limited understanding of discipline and its ethical dimension Limited use of learning resources, working towards selfdirection. General difficulty with structure and accuracy in expression. Weak academic/intellectual skills. Still mainly imitative and descriptive. Team/practical/professional skills that are not yet secure Little evidence of an information base. Little evidence of understanding of discipline and its ethical dimension Little evidence of use of learning resources. No selfdirection, with little evidence of contribution to team work. Very weak academic/intellectual skills and significant difficulties with structure/expression. Very imitative and descriptive. Little evidence of practical/professional skills Inadequate information base. Inadequate understanding of discipline and its ethical dimension Inadequate use of learning resources. No attempt at self-direction with inadequate contribution to team work. Very weak academic/intellectual skills and major difficulty with structure/expression. Wholly imitative and descriptive. Inadequate practical/professional skills No evidence of any information base. No understanding of discipline and its ethical dimension No evidence of use of learning resources of understanding of self-direction with no evidence of contribution to team work. No evidence academic/intellectual skills and incoherent structure/ expression. No evidence of practical/ professional skills 40-49% A marginal pass in module outcome(s) related to GLO at this level 30-39% A marginal fail in module outcome(s) related to GLO at this level. Possible compensation. Satisfies qualifying mark 20-29% 10-19% 1-9% 0% Fails to achieve module outcome(s) related to this GLO. Qualifying mark not satisfied. No compensation available Awarded for: (i) non-submission; (ii) dangerous practice and; (iii) in situations where the student fails to address the assignment brief (eg: answers the wrong question) and/or related learning outcomes 7 8. Assessment Offences As an academic community, we recognise that the principles of truth, honesty and mutual respect are central to the pursuit of knowledge. Behaviour that undermines those principles diminishes the community, both individually and collectively, and diminishes our values. We are committed to ensuring that every student and member of staff is made aware of the responsibilities s/he bears in maintaining the highest standards of academic integrity and how those standards are protected. You are reminded that any work that you submit must be your own. When you are preparing your work for submission, it is important that you understand the various academic conventions that you are expected to follow in order to make sure that you do not leave yourself open to accusations of plagiarism (eg: the correct use of referencing, citations, footnotes etc.) and that your work maintains its academic integrity. Definitions of Assessment Offences Plagiarism Plagiarism is theft and occurs when you present someone else’s work, words, images, ideas, opinions or discoveries, whether published or not, as your own. It is also when you take the artwork, images or computer-generated work of others, without properly acknowledging where this is from or you do this without their permission. You can commit plagiarism in examinations, but it is most likely to happen in coursework, assignments, portfolios, essays, dissertations and so on. Examples of plagiarism include: directly copying from written work, physical work, performances, recorded work or images, without saying where this is from; using information from the internet or electronic media (such as DVDs and CDs) which belongs to someone else, and presenting it as your own; rewording someone else’s work, without referencing them; and handing in something for assessment which has been produced by another student or person. It is important that you do not plagiarise – intentionally or unintentionally – because the work of others and their ideas are their own. There are benefits to producing original ideas in terms of awards, prizes, qualifications, reputation and so on. To use someone else’s work, words, images, ideas or discoveries is a form of theft. Collusion Collusion is similar to plagiarism as it is an attempt to present another’s work as your own. In plagiarism the original owner of the work is not aware you are using it, in collusion two or more people may be involved in trying to produce one piece of work to benefit one individual, or plagiarising another person’s work. Examples of collusion include: agreeing with others to cheat; getting someone else to produce part or all of your work; copying the work of another person (with their permission); submitting work from essay banks; paying someone to produce work for you; and allowing another student to copy your own work. 8 Many parts of university life need students to work together. Working as a team, as directed by your tutor, and producing group work is not collusion. Collusion only happens if you produce joint work to benefit of one or more person and try to deceive another (for example the assessor). Cheating Cheating is when someone aims to get unfair advantage over others. Examples of cheating include: taking unauthorised material into the examination room; inventing results (including experiments, research, interviews and observations); handing your own previously graded work back in; getting an examination paper before it is released; behaving in a way that means other students perform poorly; pretending to be another student; and trying to bribe members of staff or examiners. Help to Avoid Assessment Offences Most of our students are honest and want to avoid making assessment offences. We have a variety of resources, advice and guidance available to help make sure you can develop good academic skills. We will make sure that we make available consistent statements about what we expect. You will be able to do tutorials on being honest in your work from the library and other central support services and faculties, and you will be able to test your written work for plagiarism using ‘Turnitin®UK’ (a software package that detects plagiarism). You can get advice on how to honestly use the work of others in your own work from the library website (www.libweb.anglia.ac.uk/referencing/referencing.htm) and your lecturer and personal tutor. You will be able to use ‘Turnitin®UK’, a special software package which is used to detect plagiarism. Turnitin®UK will produce a report which clearly shows if passages in your work have been taken from somewhere else. You may talk about this with your personal tutor to see where you may need to improve your academic practice. We will not see these formative Turnitin®UK reports as assessment offences. If you are not sure whether the way you are working meets our requirements, you should talk to your personal tutor, module tutor or other member of academic staff. They will be able to help you and tell you about other resources which will help you develop your academic skills. Procedures for assessment offences An assessment offence is the general term used to define cases where a student has tried to get unfair academic advantage in an assessment for himself or herself or another student. We will fully investigate all cases of suspected assessment offences. If we prove that you have committed an assessment offence, an appropriate penalty will be imposed which, for the most serious offences, includes expulsion from Anglia Ruskin. For full details of our assessment offences policy and procedures, see the Academic Regulations, section 10 at: www.anglia.ac.uk/academicregs To see an expanded version of this guidance which provides more information on how to avoid assessment offences, visit www.anglia.ac.uk/honesty. 9 9. Learning Resources 9.1. Library Library Contacts Faculty of Arts, Law and Social Sciences libteam.alss@anglia.ac.uk Lord Ashcroft International Business School libteam.aibs@anglia.ac.uk Faculty of Health, Social Care and Education libteam.fhsce@anglia.ac.uk Faculty of Science and Technology libteam.fst@anglia.ac.uk Reading List Template – Anglia Ruskin University Library Resources Notes Key text Hughes, Ted (2008) Poetry In The Making, London: Faber & Faber. Books Allen, D M (ed) (1999) The New American Poetry 19451960: San Francisco: University of California Press. A classic anthology of creative writing by a 'guardian spirit of the land and language.' (Seamus Heaney) 'In a series of chapters built round poems by a number of writers including himself... [Ted Hughes] explores, colourfully and intensively, themes such as 'Capturing Animals', 'Wind and Weather' and 'Writing about People'. The purpose throughout is to lead on, via a discussion of the poems (which he does with riveting skill) to some direct encouragement to [pupils and students]to think and write for themselves. He makes the whole venture seem enjoyable, and somehow urgent...' Times Literary Supplement" A classic anthology of covering an extraordinarily creative period in the arts in the USA – includes poems by all the major ‘Beats’, the ‘San Francisco Renaissance ‘ and the New York School. Copies available form the university library. Alvarez, Al (2006) The Writer’s Voice, London: Bloomsbury. Frank Kermode described this book as ‘An impressive performance by a poet who allows nothing to come between him and the literature he loves’. A series of essays many of which seek to understand the mysterious idea of writer’s personal ‘voices’. A book that addresses both how one should write and how one should read. Copies available from the university library. Brotchie & Gooding (eds) (1995), A Book Of Surrealist Games, New York: Shambhala Publications. This is exactly what it claims to be: a guide to some of the games played by surrealist writers and artists to provide starting points for their work – games such as The Exquisite Corpse and ‘automatic’ writing and drawing, plus examples of what the surrealists produced. Copies available from the 10 university library. Ford, Richard (ed) (2008) The Granta Book of The American Short Story Vol 1, London: Granta Books. An excellent introduction to modern American short fiction, including stories by John Cheever, Eudora Welty, Raymond Carver and Ford himself. Copies available from the university library. Hughes, T & Heaney, S (eds) (2005) The Rattle Bag, London: Faber & Faber. The Rattle Bag, London: Faber & Faber. Originally marketed as a book for young readers, but now recognised as one of the most eclectic and stimulating selection of poems for any age of reader. Poems are arranged alphabetically by title, which leads to the most surprising juxtapositions and discoveries. Copies available in the university library. Hughes, T & Godwin, Fay (1995) Elmet, London: Faber & Faber. A fascinating collaboration between poet and photographer, which produced an extraordinary portrait of the Calder Valley, and especially its community’s roots in history and myth. Copies available from the university library. 52 Ways of Looking At A Poem, London: Vintage. A collection of a year’s worth of Padel’s weekly poetry column in The Independent on Sunday . Extremely good on describing different poets’ techniques in plain language. Copies available from the university library. Padel, Ruth (2004) 52 Ways of Looking At A Poem, London: Vintage. An extraordinary fifty year project in which Phillips is transforming a Victorian novel into decorated pages of found text telling a new story of Bill Toge’s pursuit of art and love. Copies available from the university library. (See also internet resources below). Phillips, Tom (2005) A Humument, London: Thames & Hudson. Reynolds, Kimberley (2011) Children’s Literature: a very short introduction, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Another of the excellent very short introduction series, which as with the other titles gives a remarkably good overview of the topic by a worldleading scholar in the field. Copies ordered for the library, but available to buy from John Smith. Sweeney, M (ed) & Fanelli, S (ill.) (2003) The New Faber Book of Children’s Poems, London : Faber & Faber. An excellent selection of children’s poetry, including many poems that aren’t included in other anthologies of children’s poetry. Very interesting graffiti-style illustrations, interrogating and sometimes lampooning the texts, by Sara Fanelli. One copy available from the university library. Online Journals and other online resources Mslexia: http://www.mslexia.co.uk/ Website of the established magazine for women writers. However, the advice and tips on the site and in the magazine are extremely useful for any writer – male or female. Narrative: http://www.narrativemagazine.com A free online magazine for writers, containing fiction, poetry and with regular competitions. Very worthwhile subscribing. Wordfest: http://www.cambridgewordfest.co.uk/ For the programme and booking details for 11 Cambridge’s own literature festival, held every year towards the end of March. Tom Phillips: http://humument.com Official site for A Humument, includes pages from previous editions and the latest pages. George Szirtes: http://www.georgeszirtes.co.uk George is a Hungarian-born poet who teaches Creative Writing at UEA. A very good site with an excellent blog that George keeps as a true diary – it’s frank, intelligent and updated daily! Additional notes on this reading list Additional reading will be recommended weekly in class. Link to the University Library catalogue and Digital Library http://libweb.anglia.ac.uk/ Link to Harvard Referencing guide http://libweb.anglia.ac.uk/referencing/harvard.htm 9.2. Other Resources 10. Module Evaluation During the second half of the delivery of this module, you will be asked to complete a module evaluation questionnaire to help us obtain your views on all aspects of the module. This is an extremely important process which helps us to continue to improve the delivery of the module in the future and to respond to issues that you bring to our attention. The module report in section 11 of this module guide includes a section which comments on the feedback we received from other students who have studied this module previously. Your questionnaire response is anonymous. Please help us to help you and other students at Anglia Ruskin by completing the Module Evaluation process. We very much value our students’ views and it is very important to us that you provide feedback to help us make improvements. In addition to the Module Evaluation process, you can send any comment on anything related to your experience at Anglia Ruskin to tellus@anglia.ac.uk at any time. 12 11. Module anthology . Elmore Leonard's Rules of Writing These are Elmore Leonard's famous Ten Rules of Writing. Leonard is an American crime writer, much praised for his ‘gritty realism’ and use of dialogue over exposition or description to keep the action of his stories moving. to quite possibly among my top three favourite writers ever. His novels include Valdez is Coming, Hombre, Get Shorty and Rum Punch (filmed as Jackie Brown). Elmore Leonard's Ten Rules of Writing Easy on the Adverbs, Exclamation Points and Especially Hooptedoodle from the New York Times, Writers on Writing Series. By ELMORE LEONARD These are rules I’ve picked up along the way to help me remain invisible when I’m writing a book, to help me show rather than tell what’s taking place in the story. If you have a facility for language and imagery and the sound of your voice pleases you, invisibility is not what you are after, and you can skip the rules. Still, you might look them over. 1. Never open a book with weather. If it’s only to create atmosphere, and not a character’s reaction to the weather, you don’t want to go on too long. The reader is apt to leaf ahead looking for people. There are exceptions. If you happen to be Barry Lopez, who has more ways to describe ice and snow than an Eskimo, you can do all the weather reporting you want. 2. Avoid prologues. They can be annoying, especially a prologue following an introduction that comes after a foreword. But these are ordinarily found in nonfiction. A prologue in a novel is backstory, and you can drop it in anywhere you want. There is a prologue in John Steinbeck’s “Sweet Thursday,” but it’s O.K. because a character in the book makes the point of what my rules are all about. He says: “I like a lot of talk in a book and I don’t like to have nobody tell me what the guy that’s talking looks like. I want to figure out what he looks like from the way he talks. . . . figure out what the guy’s thinking from what he says. I like some description but not too much of that. . . . Sometimes I want a book to break loose with a bunch of hooptedoodle. . . . Spin up some pretty words maybe or sing a little song with language. That’s nice. But I wish it was set aside so I don’t have to read it. I don’t want hooptedoodle to get mixed up with the story.” 3. Never use a verb other than “said” to carry dialogue. The line of dialogue belongs to the character; the verb is the writer sticking his nose in. But said is far less intrusive than grumbled, gasped, cautioned, lied. I once noticed Mary McCarthy ending a line of dialogue with “she asseverated,” and had to stop reading to get the dictionary. 13 4. Never use an adverb to modify the verb “said” . . . . . . he admonished gravely. To use an adverb this way (or almost any way) is a mortal sin. The writer is now exposing himself in earnest, using a word that distracts and can interrupt the rhythm of the exchange. I have a character in one of my books tell how she used to write historical romances “full of rape and adverbs.” 5. Keep your exclamation points under control. You are allowed no more than two or three per 100,000 words of prose. If you have the knack of playing with exclaimers the way Tom Wolfe does, you can throw them in by the handful. 6. Never use the words “suddenly” or “all hell broke loose.” This rule doesn’t require an explanation. I have noticed that writers who use “suddenly” tend to exercise less control in the application of exclamation points. 7. Use regional dialect, patois, sparingly. Once you start spelling words in dialogue phonetically and loading the page with apostrophes, you won’t be able to stop. Notice the way Annie Proulx captures the flavor of Wyoming voices in her book of short stories “Close Range.” 8. Avoid detailed descriptions of characters. Which Steinbeck covered. In Ernest Hemingway’s “Hills Like White Elephants” what do the “American and the girl with him” look like? “She had taken off her hat and put it on the table.” That’s the only reference to a physical description in the story, and yet we see the couple and know them by their tones of voice, with not one adverb in sight. 9. Don’t go into great detail describing places and things. Unless you’re Margaret Atwood and can paint scenes with language or write landscapes in the style of Jim Harrison. But even if you’re good at it, you don’t want descriptions that bring the action, the flow of the story, to a standstill. And finally: 10. Try to leave out the part that readers tend to skip. A rule that came to mind in 1983. Think of what you skip reading a novel: thick paragraphs of prose you can see have too many words in them. What the writer is doing, he’s writing, perpetrating hooptedoodle, perhaps taking another shot at the weather, or has gone into the character’s head, and the reader either knows what the guy’s thinking or doesn’t care. I’ll bet you don’t skip dialogue. My most important rule is one that sums up the 10. If it sounds like writing, I rewrite it. 14 Or, if proper usage gets in the way, it may have to go. I can’t allow what we learned in English composition to disrupt the sound and rhythm of the narrative. It’s my attempt to remain invisible, not distract the reader from the story with obvious writing. (Joseph Conrad said something about words getting in the way of what you want to say.) If I write in scenes and always from the point of view of a particular character—the one whose view best brings the scene to life—I’m able to concentrate on the voices of the characters telling you who they are and how they feel about what they see and what’s going on, and I’m nowhere in sight. What Steinbeck did in “Sweet Thursday” was title his chapters as an indication, though obscure, of what they cover. “Whom the Gods Love They Drive Nuts” is one, “Lousy Wednesday” another. The third chapter is titled “Hooptedoodle 1” and the 38th chapter “Hooptedoodle 2” as warnings to the reader, as if Steinbeck is saying: “Here’s where you’ll see me taking flights of fancy with my writing, and it won’t get in the way of the story. Skip them if you want.” “Sweet Thursday” came out in 1954, when I was just beginning to be published, and I’ve never forgotten that prologue. Did I read the hooptedoodle chapters? Every word. The Thought-Fox I imagine this midnight moment's forest: Something else is alive Beside the clock's loneliness And this blank page where my fingers move. Through the window I see no star: Something more near Though deeper within darkness Is entering the loneliness: Cold, delicately as the dark snow A fox's nose touches twig, leaf; Two eyes serve a movement, that now And again now, and now, and now Sets neat prints into the snow Between trees, and warily a lame Shadow lags by stump and in hollow Of a body that is bold to come Across clearings, an eye, A widening deepening greenness, Brilliantly, concentratedly, Coming about its own business Till, with a sudden sharp hot stink of fox It enters the dark hole of the head. The window is starless still; the clock ticks, The page is printed. Ted Hughes 15 Words Axes After whose stroke the wood rings, And the echoes! Echoes traveling Off from the center like horses. The sap Wells like tears, like the Water striving To re-establish its mirror Over the rock That drops and turns, A white skull, Eaten by weedy greens. Years later I Encounter them on the roadWords dry and riderless, The indefatigable hoof-taps. While From the bottom of the pool, fixed stars Govern a life. Sylvia Plath Animals There are nights when we cannot name the animals that flit across our headlights even on moonlit journeys, when the road is eerie and still and we smell the water long before the coast road, or those lamps across the bay, they cross our path, unnameable and bright as any in the sudden heat of Eden. Mostly, it’s rabbit, or fox, though we’ve sometimes caught a glimpse of powder blue, or Chinese white, or chanced upon a mystery of eyes and passed the last few miles in wonderment. It’s like the time our only neighbour died on Echo Road, leaving her house unoccupied for months, a darkness at the far end of the track that set itself apart, the empty stairwell brooding in the heat, 16 the blank rooms filling with scats and the dreams of mice. In time, we came to think the house contained a presence: we could see it from the yard shifting from room to room in the autumn rain and we thought it was watching us: a kindred shape more animal than ghost. They say, if you dream an animal, it means “the self” - that mess of memory and fear that wants, remembers, understands, denies, and even now, we sometimes wake from dreams of moving from room to room, with its scent on our hands and a slickness of musk and fur on our sleep-washed skins, though what I sense in this, and cannot tell is not the continuity we understand as self, but life, beyond the life we live on purpose: one broad presence that proceeds by craft and guesswork, shadowing our love. John Burnside The Little Box The little box gets her first teeth And her little length Little width little emptiness And all the rest she has The little box continues growing The cupboard that she was inside Is now inside her And she grows bigger bigger bigger Now the room is inside her And the house and the city and the earth And the world she was in before The little box remembers her childhood And by a great longing She becomes a little box again Now in the little box You have the whole world in miniature You can easily put in a pocket Easily steal it lose it Take care of the little box Vasko Popa 17 Poem In the stump of the old tree, where the heart has rotted out, there is a hole the length of a man's arm, and a dank pool at the bottom of it where the rain gathers, and the old leaves turn into lacy skeletons. But do not put your hand down to see, because in the stumps of old trees, where the hearts have rotted out, there are holes the length of a man's arm, and dank pools at the bottom where the rain gathers and old leaves turn to lace, and the beak of a dead bird gapes like a trap. But do not put your hand down to see, because in the stumps of old trees with rotten hearts, where the rain gathers and the laced leaves and the dead bird like a trap, there are holes the length of a man's arm, and in every crevice of the rotten wood grow weasel's eyes like molluscs, their lids open and shut with the tide. But do not put your hand down to see, because ... ... in the stumps of old trees where the hearts have rotted out there are holes the length of a man's arm where the weasels are trapped and the letters of the rook language are laced on the sodden leaves, and at the bottom there is a man's arm. But do not put your hand down to see, because in the stumps of old trees where the hearts have rotted out there are deep holes and dank pools where the rain gathers, and if you ever put your hand down to see, you can wipe it in the sharp grass till it bleeds, but you'll never want to eat with it again. Hugh Sykes Davies Opening the Cage: 14 variations on 14 words “I have nothing to say and I am saying it and it is poetry.” I have to say poetry and is that nothing and I am saying it I am and I have poetry to say and is that nothing saying it I am nothing and I have poetry to say and that is saying it I that am saying poetry have nothing and it is I and to say And I say that I am to have poetry and saying it is nothing I am poetry and nothing and saying it is to say that and it Saying nothing I am poetry and I have to say that and it is It is and I am and I have poetry saying say that to nothing It is saying poetry to nothing and I say I have and am that Poetry is saying I have it and I am nothing and to say that And that nothing is poetry I am saying and I have to say it Saying poetry is nothing and to that I say I am and have it Edwin Morgan 18 The Sea Is History Where are your monuments, your battles, martyrs? Where is your tribal memory? Sirs, in that gray vault. The sea. The sea has locked them up. The sea is History. First, there was the heaving oil, heavy as chaos; then, likea light at the end of a tunnel, the lantern of a caravel, and that was Genesis. Then there were the packed cries, the shit, the moaning: Exodus. Bone soldered by coral to bone, mosaics mantled by the benediction of the shark's shadow, that was the Ark of the Covenant. Then came from the plucked wires of sunlight on the sea floor the plangent harp of the Babylonian bondage, as the white cowries clustered like manacles on the drowned women, and those were the ivory bracelets of the Song of Solomon, but the ocean kept turning blank pages looking for History. Then came the men with eyes heavy as anchors who sank without tombs, brigands who barbecued cattle, leaving their charred ribs like palm leaves on the shore, then the foaming, rabid maw of the tidal wave swallowing Port Royal, and that was Jonah, but where is your Renaissance? Sir, it is locked in them sea sands out there past the reef's moiling shelf, where the men-o'-war floated down; strop on these goggles, I'll guide you there myself. It's all subtle and submarine, through colonnades of coral, past the gothic windows of sea fans to where the crusty grouper, onyx-eyed, blinks, weighted by its jewels, like a bald queen; and these groined caves with barnacles pitted like stone 19 are our cathedrals, and the furnace before the hurricanes: Gomorrah. Bones ground by windmills into marl and cornmeal, and that was Lamentations that was just Lamentations, it was not History; then came, like scum on the river's drying lip, the brown reeds of villages mantling and congealing into towns, and at evening, the midges' choirs, and above them, the spires lancing the side of God as His son set, and that was the New Testament. Then came the white sisters clapping to the waves' progress, and that was Emancipation jubilation, O jubilation vanishing swiftly as the sea's lace dries in the sun, but that was not History, that was only faith, and then each rock broke into its own nation; then came the synod of flies, then came the secretarial heron, then came the bullfrog bellowing for a vote, fireflies with bright ideas and bats like jetting ambassadors and the mantis, like khaki police, and the furred caterpillars of judges examining each case closely, and then in the dark ears of ferns and in the salt chuckle of rocks with their sea pools, there was the sound like a rumour without any echo of History, really beginning. Derek Walcott 20 Bye Bye Blackbird For Douglas Oliver over the clay-laden estuary a soft grey light comes sneaking it is the spirit of Coln Spring & all along the shoreline an oyster-catcher dips & bobs a splashing blur of black & white against the easterner curlews ghosting above the fleet fly our souls out of perversity Brightlingsea has grown where it is the sepia gaff-rigged sails of the smacks manoeuvre away into the Dutch hinterspace beyond Mersea Island a rich alluvium gets itself laid over years as we mooch along towards a frith dreaming of sprats and opals John James Personal Helicon for Michael Longley As a child, they could not keep me from wells And old pumps with buckets and windlasses. I loved the dark drop, the trapped sky, the smells Of waterweed, fungus and dank moss. One, in a brickyard, with a rotted board top. I savoured the rich crash when a bucket Plummeted down at the end of a rope. So deep you saw no reflection in it. A shallow one under a dry stone ditch Fructified like any aquarium. When you dragged out long roots from the soft mulch A white face hovered over the bottom. Others had echoes, gave back your own call With a clean new music in it. And one Was scaresome, for there, out of ferns and tall Foxgloves, a rat slapped across my reflection. Now, to pry into roots, to finger slime, To stare, big-eyed Narcissus, into some spring Is beneath all adult dignity. I rhyme To see myself, to set the darkness echoing. Seamus Heaney 21 The Skunk Up, black, striped and damasked like the chasuble At a funeral mass, the skunk's tail Paraded the skunk. Night after night I expected her like a visitor. The refrigerator whinnied into silence. My desk light softened beyond the verandah. Small oranges loomed in the orange tree. I began to be tense as a voyeur. After eleven years I was composing Love-letters again, broaching the word 'wife' Like a stored cask, as if its slender vowel Had mutated into the night earth and air Of California. The beautiful, useless Tang of eucalyptus spelt your absence. The aftermath of a mouthful of wine Was like inhaling you off a cold pillow. And there she was, the intent and glamorous, Ordinary, mysterious skunk, Mythologized, demythologized, Snuffing the boards five feet beyond me. It all came back to me last night, stirred By the sootfall of your things at bedtime, Your head-down, tail-up hunt in a bottom drawer Seamus Heaney Punishment I can feel the tug of the halter at the nape of her neck, the wind on her naked front. It blows her nipples to amber beads, it shakes the frail rigging of her ribs. I can see her drowned body in the bog, the weighing stone, the floating rods and boughs. Under which at first she was abarked sapling that is dug up oak-bone, brain firkin: her shaved head like a stubble of black corn, 22 her blindfold a soiled bandage, her noose a ring to store the memories of love. Little adultress, before they punished you you were flaxen-haired, undernourished, and your tar-black face was beautiful. My poor scapegoat, I almost love you but would have cast, I know, the stones of silence. I am the artful voyeur of your brain’s exposed and darkened combs, your muscles webbing and all your numbered bones: I who have stood dumb when your betraying sisters, cauled in tar, wept by the railings, who would connive in civilized outrage yet understand the exact and tribal, intimate revenge. Seamus Heaney Warming Her Pearls for Judith Radstone Next to my own skin, her pearls. My mistress bids me wear them, warm them, until evening when I´ll brush her hair. At six, I place them round her cool, white throat. All day I think of her, resting in the Yellow Room, contemplating silk or taffeta, which gown tonight? She fans herself whilst I work willingly, my slow heat entering each pearl. Slack on my neck, her rope. She´s beautiful. I dream about her in my attic bed; picture her dancing with tall men, puzzled by my faint, persistent scent beneath her French perfume, her milky stones. I dust her shoulders with a rabbit´s foot, watch the soft blush seep through her skin like an indolent sigh. In her looking-glass my red lips part as though I want to speak. 23 Full moon. Her carriage brings her home. I see her every movement in my head.... Undressing, taking off her jewels, her slim hand reaching for the case, slipping naked into bed, the way she always does.... And I lie here awake, knowing the pearls are cooling even now in the room where my mistress sleeps. All night I feel their absence and I burn. Carol Ann Duffy The Day Lady Died It is 12:20 in New York a Friday three days after Bastille Day, yes it is 1959, and I go get a shoeshine because I will get off the 4:19 in East Hampton at 7:15 and then go straight to dinner and I don't know the people who will feed me I walk up the muggy street beginning to sun and have a hamburger and a malted and buy an ugly NEW WORLD WRITING to see what the poets in Ghana are doing these days I go on to the bank and Miss Stillwagon (first name Linda I once heard) doesn't even look up my balance for once in her life and in the GOLDEN GRIFFIN I get a little Verlaine for Patsy with drawings by Bonnard although I do think of Hesiod, trans. Richmond Lattimore or Brendan Behan's new play or Le Balcon or Les Nègres of Genet, but I don't, I stick with Verlaine after practically going to sleep with quandariness and for Mike I just stroll into the PARK LANE Liquor Store and ask for a bottle of Strega, and then I go back where I came from to 6th Avenue and the tobacconist in the Ziegfeld Theatere and casually ask for a carton of Gauloises and a carton of Picayunes, and a NEW YORK POST with her face on it and I am sweating a lot by now and thinking of leaning on the john door in the 5 SPOT while she whispered a song along the keyboard to Mal Waldron and everyone and I stopped breathing. Frank O’Hara 24 The Twenty-Sixers We are the twenty-sixers: Gypsies, jugglers, necromancers. Here, sir, here we come: Fortune-tellers, cheapjack tricksters. Cross our palm, sir. Join our dance, sir, Or we’ll strike you dumb. An Angel Arguing with an Angry Ape… A Bishop Breaking Bread with a Baboon… A Carrion Crow Clad in a Crimson Cape… A Doctor of Divinity who Dreams of Doom… We are the twenty-sixers: Gypsies, jugglers, necromancers. Here, sir, here we come: Fortune-tellers, cheapjack tricksters. Cross our palm, sir. Join our dance, sir, Or we’ll strike you dumb. An Eccentric Earl with Eagles to Exhibit… A Fund to Finance Fiends who Fail to Fall… A Goblin Gabbling Grace beneath a Gibbet… The Hounds of Hopelessness who Howl around the Hall… An Intellectual Imp Inventing Interesting Ills… A Jumped-up Judge who Jokes about the Jews… The Kids in Khaki every Kind of Kingdom Kills… Lieutenant Luck who Lends them Lives to Lose… We are the twenty-sixers: Gypsies, jugglers, necromancers. Here, sir, here we come: Fortune-tellers, cheapjack tricksters. Cross our palm, sir. Join our dance, sir, Or we’ll strike you dumb. The Monstrous Maybes in the Mire of Might-Have-Been… The Nevermores that Nag you in the Night… The Odd One Out who’s Only Out at Hallowe’en… The Princess Pretty-Please who’s Painfully Polite… The Questionmark that can’t Quite Quench your Quest… The Ringing of a Right and Royal Rhyme… The Silent Song that cannot be Suppressed… The ticks and Tocks that Take their Toll of Time… We are the twenty-sixers: Gypsies, jugglers, necromancers. Here, sir, here we come: Fortune-tellers, cheapjack tricksters. Cross our palm, sir. Join our dance, sir, Or we’ll strike you dumb. The Undertakers Ugly Understudy Ulf… The Violent Vicar whom his Victims Vex… The Woman Who Went Walking With a Wolf… 25 The letter the unlettered sing with: X The Youth who Yawns but Yearns to Yell out: Yes!… The Zombie with his Zip stuck in the Zoo… But without a twenty-seventh we are less Than breaths of wind. So we have come for you We are the twenty-sixers: Gypsies, jugglers, necromancers. Here, sir, here we come: Fortune-tellers, cheapjack tricksters. Cross our palm, sir. Join our dance, sir, Or we’ll strike you dumb. Philip Gross The Instruction Manual As I sit looking out of a window of the building I wish I did not have to write the instruction manual on the uses of a new metal. I look down into the street and see people, each walking with an inner peace, And envy them--they are so far away from me! Not one of them has to worry about getting out this manual on schedule. And, as my way is, I begin to dream, resting my elbows on the desk and !!!!!!! leaning out of the window a little, Of dim Guadalajara! City of rose-colored flowers! City I wanted most to see, and did not see, in Mexico! But I fancy I see, under the press of having to write the instruction manual, Your public square, city, with its elaborate little bandstand! The band is playing Scheherazade by Rimsky-Korsakov. Around stand the flower girls, handing out rose- and lemon-colored flowers, Each attractive in her rose-and-blue striped dress (Oh! such shades of rose and blue), And nearby is the little white booth where women in green serve you green !!!!!!! and yellow fruit. The couples are parading; everyone is in a holiday mood. First, leading the parade, is a dapper fellow Clothed in deep blue. On his head sits a white hat And he wears a mustache, which has been trimmed for the occasion. His dear one, his wife, is young and pretty; her shawl is rose, pink, and white. Her slippers are patent leather, in the American fashion, And she carries a fan, for she is modest, and does not want the crowd to see !!!!!!! her face too often. But everybody is so busy with his wife or loved one I doubt they would notice the mustacioed man's wife. Here come the boys! They are skipping and throwing little things on the sidewalk Which is made of gray tile. One of them, a little older, has a toothpick in his teeth. He is silenter than the rest, and affects not to notice the pretty young girls in white. But his friends notice them, and shout their jeers at the laughing girls. Yet soon this all will cease, with the deepening of their years, And love bring each to the parade grounds for another reason. But I have lost sight of the young fellow with the toothpick. Wait--there he is--on the other side of the bandstand. Secluded from his friends, in earnest talk with a young girl Of fourteen or fifteen. I try to hear what they are saying But it seems they are just mumbling something--shy words of love, probably. 26 She is slightly taller than he, and looks quietly down into his sincere eyes. She is wearing white. The breeze ruffles her long fine black hair against her olive cheek. Obviously she is in love. The boy, the young boy with the toothpick, he is in love too; His eyes show it. Turning from this couple, I see there is an intermission in the concert. The paraders are resting and sipping drinks through straws (The drinks are dispensed from a large glass crock by a lady in dark blue), And the musicians mingle among them, in their creamy white uniforms, and talk About the weather, perhaps, or how their kids are doing at school. Let us take this opportunity to tiptoe into one of the side streets. Here you may see one of those white houses with green trim That are so popular here. Look--I told you! It is cool and dim inside, but the patio is sunny. An old woman in gray sits there, fanning herself with a palm leaf fan. She welcomes us to her patio, and offers us a cooling drink. "My son is in Mexico City," she says. "He would welcome you too If he were here. But his job is with a bank there. Look, here is a photograph of him." And a dark-skinned lad with pearly teeth grins out at us from the worn leather frame. We thank her for her hospitality, for it is getting late And we must catch a view of the city, before we leave, from a good high place. That church tower will do--the faded pink one, there against the fierce blue of the sky. Slowly we enter. The caretaker, an old man dressed in brown and gray, asks us how long we have been in the city and how we like it here. His daughter is scrubbing the steps--she nods to us as we pass into the tower. Soon we have reached the top, and the whole network of the city extends before us. there is the rich quarter, with its houses of pink and white, and its crumbling, leafy terraces. There is the poorer quarter, its homes a deep blue. There is the market, where men are selling hats and swatting flies And there is the public library, painted several shades of pale green andbeige. Look! There is the square we just came from, with the promenaders. There are fewer of them, now that the heat of the day has increased. But the young boy and girl still lurk in the shadows of the bandstand. And there is the home of the little old lady-She is still sitting in the patio, fanning herself. How limited, but how complete withal, has been our experience of Guadalajara! We have seen young love, married love, and the love of an aged mother for her son. We have heard the music, tasted the drinks, and looked at colored houses. What more is there to do, except stay? And that we cannot do. And as a last breeze freshens the top of the weathered old tower, I turn my gaze Back to the instruction manual which has made me dream of Guadalajara. John Ashbery 27 A Martian Sends A Postcard Home Caxtons are mechanical birds with many wings and some are treasured for their markings-they cause the eyes to melt or the body to shriek without pain. I have never seen one fly, but sometimes they perch on the hand. Mist is when the sky is tired of flight and rests its soft machine on the ground: then the world is dim and bookish like engravings under tissue paper. Rain is when the earth is television. It has the property of making colours darker. Model T is a room with the lock inside -a key is turned to free the world for movement, so quick there is a film to watch for anything missed. But time is tied to the wrist or kept in a box, ticking with impatience. In homes, a haunted apparatus sleeps, that snores when you pick it up. If the ghost cries, they carry it to their lips and soothe it to sleep with sounds. And yet, they wake it up deliberately, by tickling with a finger. Only the young are allowed to suffer openly. Adults go to a punishment room with water but nothing to eat. They lock the door and suffer the noises alone. No one is exempt and everyone's pain has a different smell. At night, when all the colours die, they hide in pairs and read about themselves -in colour, with their eyelids shut. Craig Raine. 28 Fishbones Dreaming Fishbones lay in the smelly bin. He was a head, a backbone and a tail. Soon the cats would be in for him. He didn’t like to be this way. He shut his eyes and dreamed back. Back to when he was fat, and hot on a plate. Beside green beans, with lemon juice Squeezed on him. And a man with a knife And fork raised, about to eat him. He didn’t like to be this way. He shut his eyes and dreamed back. Back to when he was frozen in the freezer. With lamb cutlets and minced beef and prawns. Three months he was in there. He didn’t like to be this way. He shut his eyes and dreamed back. Back to when he was squirming in a net, with thousands of other fish, on the deck Of a boat. And the rain falling Wasn’t wet enough to breathe in. He didn’t like to be this way. He shut his eyes and dreamed back. Back to when he was darting through the sea, past crabs and jellyfish, and others like himself. Or surfacing to jump for flies and feel the sun on his face. He liked to be this way. He dreamed hard to try and stay there. Matthew Sweeney. 29