What support will the UK provide? - Department for International

advertisement

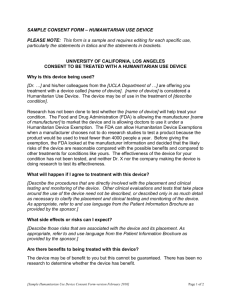

Business case and intervention summary: emergency humanitarian response Libya February – December 2011 Business case and intervention summary: emergency humanitarian response Libya, February – December 2011. Intervention summary What support will the UK provide? In Libya, the protection of civilians was a key concern. The UK, together with international partners, was committed to supporting Libyan efforts to meet basic humanitarian needs and save lives. Strong coordination amongst key humanitarian partners was critical to ensure a timely and effective response, based on international humanitarian needs. The UK’s humanitarian response to the crisis in Libya has saved lives, prevented suffering and maintained the dignity of about 1.6 million civilians affected by the conflict. What support the UK provided The UK humanitarian response has focused on three priority areas: a) b) c) Protection of civilians - to protect those caught up in the conflict; Assistance for survival - to deliver life-saving interventions and reduce suffering; Effective international humanitarian coordination – especially through the UN. Protection of civilians: We ensured civilians were protected from violence, abuse and exploitation and supported awareness-raising on international humanitarian law and human rights. The UK provided support to repatriate 12,700 people from the borders and evacuate 4,800 people from Misrata. Our support also helped to protect over a million people from mines and unexploded ordinance. Assistance for survival: We provided for immediate humanitarian needs (health, food, shelter, water and sanitation) for Libyans and third country nationals (TCNs) through international humanitarian agencies. UK support enabled 2,500 trauma related surgeries to be performed, provided emergency health supplies for 30,000 people, food for 690,000, water purification for 7,000 people and emergency shelter for the vulnerable, including 2,110 tents and 7,700 blankets. Effective International Coordination: We supported the leadership, coordination, preparedness, response and forward planning of international humanitarian agencies. The overall result was an effective UN led and coordinated humanitarian response, which provided timely assistance based on humanitarian needs. How support was provided The UK has delivered humanitarian aid in a fast and flexible way, on the basis of needs, value for money and focused on delivering results and impact. The delivery of our support has been channelled in large part through multilateral humanitarian partners, who are best placed to deliver aid quickly to respond to urgent needs. We built on our knowledge of effective agencies and the results of the recent DFID Multilateral Aid Review, which enabled Ministers to rapidly allocate support to effective agencies such as the International Committee of the Red Cross and UN High Commission for Refugees. The UK has provided humanitarian support in a range of ways including: Technical Assistance: DFID humanitarian advisers on the Tunisian and Egyptian borders, in Malta, Cairo and Libya itself and air operations advisors seconded to UNHCR; In kind support: We provided tents, blankets and flights directly to humanitarian agencies dealing with those in need of shelter and repatriation at the borders; Partner funding: We contributed to the UN emergency appeals, including funding for IOM, UNHCR, ICRC, UNICEF, MAG, WHO and IMC; Advocacy: We have called for free and unfettered humanitarian access to affected populations and lobbied other donors to support humanitarian efforts in Libya. Total funding An allocation of £18.4 million for humanitarian assistance. Period of funding: February 2011 – December 2012. Why is UK support required? The uprising that began in February 2011 triggered a political and security crisis across Libya. A timely response from the UK helped to prevent a logistical problem from developing into a humanitarian emergency when large numbers of people fled over the borders. The UK response was instrumental in galvanising action from the rest of the international community. As the crisis unfolded, humanitarian needs emerged and the situation evolved from a border problem to a focus on areas of conflict in Libya, which required a range of needs to be met. The east of the country quickly regained a degree of normal life (though pockets of need remained), but conditions in the west were difficult as fighting intensified and access was restricted. In particular, urgent relief was required in the city of Misrata which had been under siege by Qadhafi’s forces for several weeks. Other areas affected by conflict such as the Nafusah Mountains, Tripoli and Sirte, also required humanitarian assistance. From the onset, the UK took a leadership role in responding to the humanitarian situation through its role in the UN and in leading the humanitarian response with the US, Australia and the EU. The UK was one of the first to respond and support the ICRC and other specialised agencies such as IMC, UNICEF and WHO. This included support for the provision of doctors, medical supplies, medical equipment and food. The UK also directly provided 2,110 tents and 7,700 blankets to shelter Libyans driven out of their homes by the fighting, and supported IOM to evacuate 4,800 vulnerable migrant workers and injured civilians from Misrata. The UK focused on areas where it could add value, using our comparative advantage as a fast, flexible donor and ensured that we supported interventions that offered a timely, appropriate and high quality response. We worked to identify and meet gaps in the humanitarian response that others were not able to address. We were well placed to do this through our advisers on the ground, who assessed and monitored the humanitarian situation. Post-conflict, DFID humanitarian activities continue to play an important role in supporting early recovery efforts. Our support for demining will help protect over a million civilians from death or injury from unexploded ordnance and will help thousands of people return safely to their homes. The ICRC continues to work with the Libyan authorities in order to support returnees to Sirte and Bani Walid, to address the protection needs of vulnerable minority groups, and to address other residual humanitarian needs in areas including health and shelter. WHO continues to work with DFID funds to provide medical teams and support. We will facilitate a smooth transition from humanitarian aid to early recovery, by supporting local Libyan authorities to provide services and phase out humanitarian assistance quickly. What are the expected results? The UK Government’s humanitarian response to the crisis in Libya has saved lives, prevented suffering, and supported the dignity of civilians affected by the conflict. Overall, the range of UK interventions has supported up to 1.6 million people. The results in the priority areas set out in the Strategic Humanitarian Framework were: (a) Protection of civilians We ensured civilians were protected from violence, abuse and exploitation and supported awareness-raising on international humanitarian law and human rights. The results were to provide the vulnerable with life-saving emergency shelter (2,110 tents and 7,700 blankets), to repatriate 12,700 third country nationals from the Tunisian border and evacuate 4,800 migrant workers and injured civilians from Misrata. We also helped to protect over one million people (including 450,000 children) from the dangers of mines and unexploded ordinance in Misrata, Benghazi, Adjabiya, Brega, Ras Lanuf and the Western Mountains. (b) Assistance for Survival We provided for immediate humanitarian needs (health, food, shelter, water and sanitation) for Libyans and Third Country Nationals through support to ICRC, WHO, UNICEF, WHO, IMC and UNHCR. The results on health include over 20,000 patients treated, over 2,500 surgical operations and over 450 patients medically evacuated, the provision of emergency health supplies for 30,000 people and early development support for 3,750 children. Food was provided for 690,000 people and water distribution and purification for 7,000 people. (c) Effective International Coordination The UK supported the leadership, coordination, preparedness, response and planning of international humanitarian agencies, including through the in-country cluster system. The overall result was an effective UN led and coordinated humanitarian response, which ensured contingency plans were in place and provided timely assistance based on humanitarian need. UK humanitarian assistance to the Libya Crisis 2011 One humanitarian advisor to Ankara as part of UK-Turkey-US planning cell 26 February DFID deploys humanitarian advisers to Libyan borders with Egpyt and Tunisia 8 April DFID deploys humanitarian adviser to Benghazi, Libya ICRC - Food, medical support, protection and other emergency assistance £5,000,000 Shelter - tents and blankets £1,480,000 Repatriation of third country nationals - in-kind donation of flights £2,600,000 18 April Support evacuation of 4,800 migrants and injured people from Misrata port (IOM) 18 April Medical staff, supplies and evacuations in Misrata and Nafusah Mountains (IMC) 9 March Medical and other essential assistance to vulnerable people at borders (ICRC) Uprising begins mid-February Medical supplies, staff and coordination and emergency food and non-food items £1,030,000 2 April Further tents and blankets displaced people at borders and in Libya (UNHCR) 2 and 18 March Repatriation of 12,700 migrants from the borders (IOM) Mar Humanitarian coordination and deployment of humanitarian teams £1,025,000 Repatriation and evacuation of third country nationals by IOM £6,000,000 for 4 March 3 Air Operations specialists to facilitate repriations (UNHCR) Feb UK Humanitarian Spend 7 April Medical, food and other emergency supplies to Misrata (UNICEF) 1 March Tents and blankets for displaced people at borders (IOM/UNHCR) Jan Total UK humanitarian support to the Libya crisis £18.4 million Apr May Siege of Misrata 4 June Clearance of explosive remnants of war in Misrata, Ajdabiya and other areas (MAG) Jun Jul Clearance of explosive remnants of war £1,267,995 27 August Medical, food, protection and other help to western Libya including Tripoli (ICRC) Aug Sep 15 Sept and 17 Oct Further support to clearance of September DFID deploys humanitarian explosive remnants of war eastern and western Libya, team to Tripoli including newly accessible areas (MAG and UNMAS) Oct Nov Dec Emerging peace in eastern Libya Thousands flee across Libya’s borders Conflict focuses on Nafusah Mountains and Misrata, then Tripoli, Sirte and Bani Walid Libya’s liberation declared, interim government in place NTC forces take control of Tripoli and other parts of western Libya – basic services temporarily disrupted in Tripoli Transitional Government Declared Strategic case A. Context and need for DFID intervention The political context The Libyan crisis began in February 2011 when Colonel Qadhafi’s regime responded to a series of peaceful protests with military force. The United Nations Security Council passed an initial resolution (UNSCR 1970) on 26 February 2011 which, amongst other things, froze the assets of the Qadhafi regime and referred the actions of his government to the International Criminal Court for investigation. On 17 March 2011 the Security Council passed a further resolution (UNSCR 1973) which authorized member states to establish and enforce a no-fly zone over Libya and to use all necessary measures to protect civilians. The need for humanitarian intervention Humanitarian impact at Libya’s borders In February 2011 large numbers of people including migrant workers began to leave the country to escape the conflict, putting great pressure on Libya’s borders with Egypt and Tunisia. Camps were established at the borders to shelter those fleeing the conflict and many people were hosted by local families. By the end of February, over 147,000 people had left Libya to neighbouring countries, including over 75,000 to Tunisia and 69,000 to Egypt, and the flow of this exodus was continuing. OCHA reported that over 7,000 third country nationals (TCNs) crossed the Libya-Tunisia border on 1 March 2011, and over 24,000 were waiting for onward transfer from the border. Humanitarian impact within Libya Sustained fighting in areas such as the Nafusah mountains and Misrata led to the deaths and injuries of civilians, as well as combatants. Sieges of the city of Misrata and of towns in the Nafusah mountains restricted the channels for delivery of food and medical supplies. In areas such as the Nafusah mountains power and water supplies were also cut, as reported in UN assessment missions in June and July 2011. Many medical and other key workers had fled as a result of the conflict. Property, infrastructure and livestock were damaged. In the wake of the conflict in Tripoli and the surrounding towns in August 2011, high numbers of war-wounded put pressure on hospitals which were short of staff and supplies. The main water supply to Tripoli and other parts of western Libya was cut for several weeks during the fighting. In areas of conflict and areas under the control of the Qadhafi regime, access for humanitarian actors was constrained. The conflict caused many people to be displaced within Libya. The fall of Tripoli in August 2011 led to a significantly improved security situation in most parts of Libya, although there was a protracted battle for Sirte and Bani Walid which continued until mid-October. Humanitarian agencies, including the UN, were able to operate and lead their responses from Tripoli. Ongoing challenges The conflict has left significant contamination from explosive remnants of war and unsecured munitions in many areas, as highlighted by the Joint Mine Action Coordination Team (JMACT). There have been some reports of migrants and vulnerable groups (such as tribes accused of supporting the Qadhafi regime) being subject to abuse and arbitrary detention. Global response and burden-sharing The UN led the coordination of humanitarian assistance to Libya. The UN released in March 2011 a three month Flash Appeal (including UN agencies and NGOs) for Libya for $160m (£97.9m) which was revised in May up to $408 million. In September following the NTC taking control of Tripoli, OCHA published a 30-day humanitarian action plan for Libya, which was followed by a 90-day plan for UN/NGO support until the end of 2011. The ICRC also made emergency appeals (total of 77 million Swiss francs by May). Throughout the crisis, the top four humanitarian donors were the US, EU, Australia and UK (providing a total of $234 million between them). Regional partners have provided significant humanitarian donations. United Arab Emirates (9th largest donor), Turkey, Kuwait and Qatar have made both in-kind and financial contributions and the Organisation of Islamic Conference has contributed $5 million. Rationale for international action Providing food and clean water, medicines and shelter saves lives. Furthermore, a population that has been fed, sheltered and kept free from sickness during a conflict is better able to start work again when it comes to post-conflict recovery. As well as the humanitarian imperative to provide assistance, UN resolutions on Libya authorised member states to use all necessary measures to protect civilians. UK’s Strategic Framework for Libya DFID developed a ‘Strategic Humanitarian Framework’ for the Libya Crisis which set out the approach and principles of the UK’s humanitarian response, consistent with the HERR. In light of the needs emerging on the ground, the UK focussed on three main areas: Protection of civilians Assistance for survival Effective international humanitarian coordination The following diagram “UK humanitarian assistance to the Libya Crisis 2011” depicts the development of the conflict over time and the corresponding humanitarian assistance provided by the UK. UK humanitarian assistance to the Libya Crisis 2011 Support provided (dates announced) and context Uprising begins midFebruary Conflict in Nafusah Mountains and Misrata, and other areas of western Libya 18 April Medical staff, supplies and evacuations in Misrata and Nafusah Mountains (IMC) 26 February DFID deploys humanitarian advisers to Libyan borders with Egpyt and Tunisia Thousands flee across Libya's borders 1 March Tents and blankets for displaced people at borders (IOM/UNHCR) 2 and 18 March Repatriation of 12,700 migrants from the borders (IOM) 4 March 3 Air Operations specialists to facilitate repriations (UNHCR) 9 March Medical and other essential assistance to vulnerable people at borders (ICRC) Emerging peace in eastern Libya 8 April DFID deploys humanitarian adviser to Benghazi, Libya 4 June Clearance of explosive remnants of war in Misrata, Ajdabiya and other areas (MAG) 2 April Further tents and blankets for displaced people at borders and in Libya (UNHCR) NTC forces take control of Tripoli and other parts of western Libya - basic services temporarily disrupted in Tripoli 27 August Medical, food, protection and other help to western Libya including Tripoli (ICRC) Siege of Misrata 7 April Medical, food and other emergency supplies to Misrata (UNICEF) Emerging peace in most areas of western Libya 15 Sept and 17 Oct Further support to clearance of explosive remnants of war eastern and western Libya, including newly accesible areas (MAG and UNMAS) 18 April Support evacuation of 4,800 migrants and injured people from Misrata port (IOM) Libya's liberation declared 23 Oct January February March April May June July August September October November B. Impact and outcome expected The UK Government’s humanitarian response to the crisis in Libya has saved lives, prevented suffering, and supported the dignity of civilians affected by the conflict. Overall, the range of UK interventions has supported up to 1.6 million people through the three areas of our Strategic Framework: protection of civilians, assistance for survival and effective international humanitarian coordination. Protection of civilians The pressure of migrants on Libya’s borders with Egypt and Tunisia presented a logistical problem which threatened to develop into a humanitarian emergency if swift action was not taken. The UK was one of the first to respond, repatriating over 12,700 migrant workers and providing tents and blankets for emergency shelter. This action helped prevent a wide scale humanitarian crisis and led the way for other members of the international community to assist with evacuations and repatriations. Within Libya, the UK provided tents and blankets to give emergency shelter to people driven out of their homes by ongoing fighting. Through the IOM we also helped evacuate 4,800 migrant workers and injured people from Misrata during a two month siege by Qadhafi’s forces. DFID humanitarian support continues to play an important role in protecting civilians and supporting early recovery efforts. Funding to Mines Advisory Group (MAG) is enabling the clearance of explosive remnants of war in different areas of Libya to protect up to one million people from unexploded devices. Further support to UNMAS for de-mining activities will enable them to expand emergency mine clearance work, including in the areas of Sirte and Bani Walid, and will contribute to assisting thousands of people to return to their homes. Assistance for survival Meeting the emergency survival needs of those within Libya during the conflict was critical. The UK supported the IMC to supply urgently needed medical supplies and medical personnel to treat wounded and other patients in areas most affected by the fighting and therefore least able to cope. The UK funded the WHO to provide medicines and training to support the provision of medical care in Libya. We also supported UNICEF to bring vital supplies into Misrata by ship, such as food, water and hygiene kits. In support of both protection and assistance for survival, the UK provided humanitarian support through the ICRC regional appeal, both at the outset of the crisis to meet immediate humanitarian needs, and again in August to help to deal with the new challenges including on health and further protection of civilians. Results expected from the ICRC’s overall appeal include: treating 5,000 war-wounded patients; providing food and household items to 690,000 people, enabling access to water for 5,000 people and providing hygiene items for 84,000 people. Effective international humanitarian coordination The UK supported the leadership, coordination, preparedness, response and forward planning of international humanitarian agencies. The outcome was an effective UN led and coordinated humanitarian response, which ensured contingency plans were in place and provided timely assistance based on humanitarian needs. More specifically, DFID staff in London and deployment of DFID humanitarian teams in Tunisia, Egypt and Libya helped to: promote effective contingency planning for possible scenarios during the conflict, including movement of people across the Libyan borders; facilitated the coordination of repatriations from the Tunisian border, through the secondment of three air operations advisors; and promoted dialogue in key humanitarian agencies on their staffing plans, including skills mix and staffing levels. For a thematic breakdown of UK humanitarian assistance to the Libya crisis, please see Pie Chart below. For a full list of results by intervention, please see the Cost/Benefit/Value for Money section within the Appraisal Case below. UK humanitarian support to the Libya crisis Humanitarian coordination and deployment of humanitarian teams £1,025,000 Repatriation and evacuation of third country nationals by IOM £6,000,000 Medical supplies, staff and coordination and emergency food and non-food items £1,030,000 Total UK humanitarian support to the Libya crisis £18.4 million ICRC - Food, medical support, protection and other emergency assistance £5,000,000 Shelter - tents and blankets £1,480,000 Repatriation of third country nationals - in-kind donation of flights £2,600,000 Clearance of explosive remnants of war £1,267,995 Appraisal case A. Proposal DFID developed a ‘Strategic Humanitarian Framework’ for the Libya Crisis which set out the approach and principles of the UK’s humanitarian response. The UK proposed to focus on three main areas: Protection of civilians Assistance for survival Effective international humanitarian coordination Counterfactual Without the live-saving and protection interventions described above, the humanitarian impact on the civilian population of Libya would have been much greater: o Protection of civilians: Without repatriations from the borders and evacuations from Misrata, the number of TCNs left without shelter, food and water would have been much higher. Without repatriations from the borders, numbers in the camps would have built up and a humanitarian crisis may have developed. o Assistance for survival: Without providing emergency health support, morbidity rates from the conflict would have been higher. o Effective international humanitarian coordination: Without an effective early humanitarian response, integrated with HMG’s wider political and economic actions, unrest in Libya and on its borders could potentially have been worse and more destabilising for the region. Full appraisal of each of the intervention options is included in Intervention Review Sheets. The Theory of Change diagram overleaf shows the chain of causality from inputs (funding, goods in kind, staff resources) to impacts on people affected (such as lives saved and people protected from explosive remnants of war). Theory of Change for Libya Humanitarian Response Funding: An allocation of £18.4 million. Goods in Kind: to humanitarian agencies dealing with those in need of shelter or repatriation Inputs Process Outputs Engagement with international h’tarian agencies in country and at HQ level Protection of Civilians from violence, abuse and exploitation, ensuring basic human rights are respected. Assumptions Outcomes Impact Both parties to the conflict are willing to accept and abide by IHL. •Repatriations of migrant workers from the borders. •Support to evacuate nearly 5,000 civilians and migrant workers from Misrata. •Protection for over 1m people from unexploded ordnance. Technical Assistance: deployment of humanitarian experts on the Tunisian and Egyptian borders, Cairo, Benghazi and Tripoli. Secondment of Air Operations experts. London Staff Time: Team of between 4 and 10 humanitarian advisers, information officers, programme managers and managerial staff. Engagement with other donors: Regular telcons to coordinate support Assistance for Survival: Providing for immediate needs (health, water, sanitation, shelter, food) for Libyans and TCNs. Effective International Coordination: Improved leadership, coordination, preparedness and response by international agencies. Access for humanitarian agencies is possible. Information on needs is triangulated and reasonable estimates of need are made. UN able to scale up and gain access and permanent presence in Libya. Provision of life-saving shelter to people at the borders. Through support to the ICRC, contributed to: •Treating 5,000 warwounded; •Reuniting families •Providing food and other items to 690,000 people. Through support to WHO, UNICEF and IMC, saved lives and eased suffering. Promotion of contingency planning at the Libyan borders. Help to facilitate coordination of repatriations from Tunisian border, through secondment air operations advisors. Support to key humanitarian agencies on their staffing plans. Lives saved, suffering reduced and dignity maintained of over 1.6 million people affected by the Libya crisis. B. Strength of the evidence base Evidence rating Medium Likely impact on climate change and environment Risks and impacts (negatives) Opportunities (positives) There is an environmental impact from conducting the evacuation of Third Country Nationals (TCN) by air. However, this was the only viable option. More people could be moved much faster by air than any other means, meaning also that logistical problems – including any health, hygiene and sanitation issues associated with build up of people - were avoided at border areas. DFID also ensured that larger groups of people from the same country were repatriated at the same time, thus reducing the number of flights taken. Risk of adverse environmental The Mines Advisory Group responsible for mines impact from procedures used clearance has a policy of minimising environmental to clear unexploded remnants impact from clearance by ensuring that environmental of war. impacts are addressed in detailed clearance plans. The Mines Advisory Group has stated that standards and learning from other programmes on environmental management will be used in Libya. There are risks to human health, biodiversity and other natural resources (e.g. soils/land) posed by the toxic substances that are associated with explosive remnants of war. Clearance of these remnants has a positive environmental impact. Risk that the activities of DFID is working with all those agencies to ensure that partner organisations (e.g. there is adequate environmental awareness and a UNICEF, ICRC, WHO, IMC proportionate response to potential environment impacts and UNHCR) have an adverse in humanitarian situations. All these partners have environmental effect. For climate and environment policies and procedures and example, providing medical have experience of applying these in humanitarian and sanitation support can situations. When the opportunity arises we will have an effect on the investigate how these climate/environment policies and environment. procedures were applied, with a view to identifying any lessons learnt for the future. Temporary camps and UNHCR recognises the potential damage that camps settlements can have an and settlements can have on the environment, as well as adverse effect on the on the local economy and relations with host environment. communities. To this end, the refugee agency has developed an overarching policy to deal with environmental issues. Equally important, UNHCR develops and supports a range of field projects that help reduce or overcome some of the damage caused by humanitarian operations. UNHCR also responds to new, emerging threats such as climate change. A full environment assessment is attached at Annex 2. C and D. Costs, benefits and value for money assessment Total Costs £18.4m Total Benefits Approximately 1.55 million direct and indirect beneficiaries of repatriation and evacuation, food and medical assistance, shelter, protection from explosive remnants of war and other emergency assistance due to UK support. Approximate average cost per person assisted/expected to be assisted: £12. Breakdown of costs, benefits and summary value for money assessment by humanitarian intervention: Partner Costs WHO Total: £400,000 Expected benefits/ beneficiaries Support the deployment of external medical teams. Approx. cost per beneficiary: £33 Provide essential drugs, medical supplies and equipment to help treat 4,000 to 5,000 trauma patients 2,000 chronically ill patients 180-200 TB patients 43 HIV patients 5,000 to 6,000 pregnant women and new born babies Build the capacity of local health staff. Help coordinate the overall emergency health response for Libya. Total beneficiaries expected: Approx. 12,233 WHO medical support value for money summary: o Salaries provided are in line with the UN salary scale. o Cost of capacity building activities are reasonable ($100 per person trained) o Costs per unit of output are clear. o The MAR assessment (see below) of WHO was variable. The MAR states that for WHO “there is evidence that procurement is driven by value-for-money”. o WHO is a well-placed agency to provide quality assured medicines, appropriate training and supervision of medical staff due to their mandate of co-working with the MoH. o Overall, the cost of £33 per beneficiary represents good value for money. ICRC For full results expected see ICRC’s Budget Extension Appeal dated 20 May 2011 for Libyan Armed Conflict REX 2011/277. Examples of results DFID has for the whole appeal include the following. Actual funded approx. activities may change depending on needs 8% of ICRC’s throughout the crisis: Appeal for the By end of April, 89,195 persons/17,839 Libya households had received a one-month food Crisis. ration. By the end of April, some 42,000 persons/8,400 Approx cost per households had received essential household beneficiary due items. to DFID funding: By the end of April, some 84,000 persons had approx/less than received essential items, in particular hygiene £31. items. Provide up to 500,000 conflict-affected people (100,000 households), including IDPs, their host families and foreigners affected by the situation and awaiting repatriation, with a single one-month food ration (or for fewer people, repeated rations). Provide up to 390,000 conflict-affected people (78,000 households), including IDPs, their host families and foreigners affected by the situation and awaiting repatriation, with essential household items. Provide up to 280,000 foreigners along the Libyan border with one-off kits of essential household and hygiene items; support the management of one kitchen in Choucha camp (more than 375,000 hot meals served to some 187,000 people) until mid-April. At the Egyptian border, as from May, provide regular breakfasts to a daily average of 1,100 people fleeing the situation in Libya and awaiting their transfer, repatriation or resettlement; be ready to provide bottled water, food items and other emergency essential items to cover a temporary shortfall in supply by other organizations (new). In Libya, help up to 500,000 people access the water they need. In Tunisia, build and maintain the water supply and sanitation equipment at Choucha camp (hosting up to 20,000 people) and help the local water boards in towns along the border (Ben Guerdane and Tataouine), hosting most of the people arriving from Libya, to improve the water supply and distribution network to the benefit of some 100,000 people. Total: £5,000,000 In Libya, on the basis of needs, help health facilities provide services, in particular those that face an increased number of patients because of the presence of IDPs and those isolated by the armed conflict and therefore not receiving their regular medical supplies. In Tunisia, provide basic medical supplies and consumables to health facilities providing services to people fleeing the situation in Libya and to Tunisians to help them cope with the increased number of patients. Total beneficiaries expected: Approx/over 2,000,000 Total beneficiaries attributable to DFID contribution (~8%): Approx/over 160,000. ICRC appeal value for money summary: o The MAR gave the ICRC a very strong rating for their value for money. It has strong systems for financial accountability and the ability to change the focus of project activities to ensure that they are always appropriate to the context and needs based. o ICRC does not present a detailed budget with its appeals and no procurement specifics are given. DFID accepts this under its framework agreement with the ICRC. o In Libya, the ICRC was one of the few agencies on the ground from the early stages of the conflict. It had also strong links with the Libyan Red Crescent. These factors put it in a unique position to identify and respond to humanitarian needs and to scale up operations effectively. o The cost per beneficiary of £33 is modest compared to the benefits and results. Repatriations and evacuations (IOM), including in-kind donation of flights Total: £8,600,000 Total average cost per beneficiary: £491 Repatriation of 12,700 TCNs from the Tunisian border by air Supported the evacuation of approximately 4,800 TCNs from Misrata (by sea). Total expected beneficiaries: 17,500 Repatriations/evacuations value for money summary: o Of the flights procured by DFID, flights to Egypt were at a cost of approximately £430 (US$700) per person, and flights to Bangladesh were approximately £960 (US$1,500) per person. IOM costs were comparable to this, equating to US$1,000 per person repatriated, based on an average cost of US$1,500 for a person repatriated to Asia and US$900 for a person repatriated to Africa. o This is a very high cost per capita for a humanitarian intervention. However, the cost of supporting someone in a camp, combined with an estimated opportunity cost of lost incomes, is at least US $580 per capita per month for the first month, with the cost rising the longer the situation continues. Paying camp costs would still leave the problem of getting people home eventually. o IOM looked at options for repatriation by sea too and used the option which provided best value for money in terms of cost, speed and effectiveness. Evacuations from Misrata were conducted by sea. o We considered the option of charging beneficiaries for flights. However, this would have been administratively complex and could have contributed to law and order issues in camps. There was also little evidence that most people in the camps were able to get home unaided. UNICEF £130,000 Total approx. cost per beneficiary: £2-4 High energy protein biscuits for 10,000 people Emergency health kits including obstetric equipment (for health centres) for 30,000 people 5,000 family hygiene kits for 10,000 people 700 water purification kits- enough for 7,000 people 2 midwifery kits to cover 100 deliveries (including surgery) 75 early childhood development kits to benefit 3750 children. Total expected beneficiaries: Approx 60,850 UNICEF supplies value for money summary: o Because the cost of transporting these supplies into Misrata by boat was covered by WFP, DFID funds only paid for the UNICEF supplies themselves and the Libyan Red Crescent distributed items. o As a result, this was an extremely low cost method of getting important supplies into Misrata. The cost of the package is approximately £4 per person. o The MAR highlighted that UNICEF provides good value for money. UNHCR/ in-kind donation of shelter items £1,480,000 Approx cost per beneficiary: £23-£86 2,110 tents (for approx 10,500 people) and 7,700 blankets delivered to coastal areas including Tobruk and Misrata 38,000 blankets and 1,400 tents (for approx 7,000 people) delivered to the Tunisian border camp Total expected beneficiaries: up to 63,200. UNHCR shelter value for money summary: o The quickest way to provide immediate shelter for up to 2100 families in Eastern Libya was to fly tents from DFID warehouses in Dubai . Tents cost approximately £70 per head or £360 per family, at a ratio of 5 persons per family. o The tents were specialist winterised tents which are necessary for North African conditions at that time of year, and DFID is the only agency with a stockpile. o There were no better ways of providing immediate and appropriate shelter quickly and flexibly. o Shelter items had been procured directly by DFID CHASE which ensures value for money through its procurement processes. IMC medical support £500,000 Approx cost per beneficiary: £20 464 medical evacuations Total of 20,976 consultations and 2,684 surgeries provided in Misrata and the Western Mountains Total expected beneficiaries: Up to approx 24,000. IMC value for money summary: o DFID scrutinised IMC’s budget carefully and the costs are appropriate and proportional given the goods and services delivered and the intended impact. o IMC was the first international organisation into Benghazi and has been extremely active and successful in reaching populations where there were medical needs. At the time that funds were committed, no other organisation was proposing these activities. o IMC’s prior set up in Libya reduced the need for start up costs in this proposal, such as staff, office space in Benghazi etc. MAG UXO clearance £767,995 Up to 1,000,000 people (directly and indirectly) made safer by clearance of unexploded ordnance (UXO) and risk education Approx. cost per beneficiary (direct and Total expected direct and indirect beneficiaries: Up to indirect): 1,000,000 £1 MAG UXO clearance value for money summary: o DFID assessed the intervention would be at a cost of about £1.00 per person directly or indirectly affected. Value for money considerations include not only lives and limbs that can be saved but also ongoing economic benefit of usable land. For example, the value of agricultural production from cleared land can be between $13,000 to over $500,000 per square kilometre per year. o MAG is a globally recognised agency with an excellent track record for mine/UXO clearance with a clear expertise in awareness campaigns which provide essential safety to local populations. o The mobilisation and deployment of staff was expected to be swift as MAG had a well established operational presence in Benghazi and was already working with the National Transitional Council (NTC) and Joint Mine Action Coordination Team (JMACT). Economies of scale have helped minimise costs contributing additional value for money. UNMAS UXO clearance £500,000 Approx cost per beneficiary (direct and indirect): £2 200,000 people (directly and indirectly) made safer by UXO clearance and risk education Reduction in the number of reported injuries and deaths as a percentage of the baseline (produced in May 2012) of 25%. Mines risk education to 16,000 people Support to coordination of UXO clearance activities in Libya, including set up of a countrywide clearance coordination unit to work with NGOs and private sector companies. Total expected beneficiaries (direct and indirect): Approx. 216,000 UNMAS value for money summary: o UNMAS engaged UNOPS to manage competitive procurement and tendering processes for clearance work to ensure maximum value for money. o Value for money considerations include not only lives and limbs that can be saved but also the ongoing economic benefit of usable land. For example, the value of agricultural production from cleared land can be between $13,000 to over $500,000 per square kilometre per year. o UNMAS leads on coordinating explosive remnants of war (ERW) work in Libya through the joint UN/NGO Joint Mine Action Coordination Team (JMACT) as well as directing the implementation of some of this work. o UNMAS will also work with local authorities to build up local capacity with a view to handing over UXO clearance responsibility to a national body. o Cost per beneficiary is higher than MAG because the UNMAS project includes start up and coordination costs which will provide a foundation for further work and ensure effective longer term mines clearance coordination and scale up. In view of these wider benefits the intervention demonstrates good value for money. Deployment of humanitarian teams £920,000 DFID humanitarian teams were deployed to the Tunisian and Egyptian borders and to Benghazi and Tripoli as access allowed. This enabled policy and programming decisions taken by Ministers to be based on clear and timely evidence of needs on the ground; Humanitarian specialists were contracted through DFID CHASE contracting procedures therefore ensuring value for money. The deployment of humanitarian teams provided effective support across all UK humanitarian interventions at a cost of 5% of the total humanitarian spend, which represents good value for money. UNHCR Air Operations specialists £105,000 Three air operations specialists for one month, followed by two for a further month, assisted with large scale air evacuation of third country nationals from Libya and its borders. Specialists were contracted through DFID CHASE contracting procedures which ensure value for money in procurement. The cost of seconding the air operations specialists was less than 2.5% of the UK contribution to the repatriations and helped ensure that this funding was used effectively. NB: Value for money considerations include cost, speed/timeliness, and quality/effectiveness of intervention. There may be overlap in numbers of beneficiaries but it is not possible to determine whether this is the case given the nature of the crisis. Processes for determining value for money UK support for the Libya humanitarian response has been delivered using three mechanisms: 1. Arrangements with multilateral humanitarian agencies (MoUs) 2. Arrangements with international NGOs (Accountable Grants) 3. Direct DFID CHASE procurement. 1. MoUs/contribution arrangements with multilateral agencies 2. Accountable grants 3. Direct DFID procurement WHO medical supplies, staff and coordination IMC UK - medical assistance to Northern Libya In-kind donation of flights for repatriation of third country nationals ICRC Libya Crisis: food, NFIs, medical supplies, and assistance to national societies MAG clearance of explosive remnants of war Provision of shelter (tents and blankets) UNICEF Emergency Supplies to Misrata, Libya. Deployment of Humanitarian Teams Repatriation and evacuation of third country nationals through IOM Secondments to UNHCR Air Operations UNHCR distribution of tents and blankets UNMAS clearance of explosive remnants of war 1. Contributions to multilateral agencies Five of the agencies to whom we are providing support (IOM, UNHCR, UNICEF, ICRC and WHO) were extensively reviewed under the Multilateral Aid Review (MAR). The MAR examined more than 40 multilaterals receiving funds from DFID against a set of criteria. The MAR drew on a range of evidence including: survey data; other studies of effectiveness; external evaluations; reporting by the multilaterals; visits by DFID staff; consultation with developing country partners; and submissions to the review from UK civil society and the organisations themselves. The MAR provides DFID with the evidence needed to take decisions on how to deliver funding through multilaterals to make the greatest possible impact on poverty. o IOM – In Libya, the IOM was the best placed organisation to support the movement of people affected by the conflict. Although the MAR rated the IOM as weak overall, it also noted that it had largely good results on delivery against project targets. UK support to IOM’s response to events in Libya was targeted specifically for evacuations and repatriations, taking advantage of the IOM’s strength. o UNHCR - the MAR highlighted the expertise that UNHCR has in providing assistance to displaced persons, although experience in supporting air operations is more limited. It needed additional air operations capacity urgently to support the scaling up of evacuations from the Libyan borders, and DFID was able to provide this rapidly in order to ensure that the large scale logistical challenge was met effectively. o UNICEF - the MAR highlighted that UNICEF provided good value for money, that UNICEF plays a unique role in addressing the issue of children in conflict, which involves monitoring, reporting and responding. UNICEF is one of the few organisations working on child protection, which is a rapidly expanding area of its work. o ICRC - the MAR gave the ICRC a very strong rating for their value for money. The MAR said ICRC manages limited resources effectively and allocates aid according to agreed schedules. Its built up reserves allow it to pre-fund operations before donor funds have been made available. It has strong systems for financial accountability and the ability to change the focus of project activities to ensure that they are always appropriate to the context. o WHO – The MAR assessment of the WHO was variable. WHO has systems in place to review organisation effectiveness, and there is evidence that procurement is driven by value for money. It also found that WHO works well with partner governments. We are cognisant of these issues with WHO and have spent sometime extracting assurances from them that they have these issues addressed for the Libya context. As well as utilising the information provided by the MAR, we have ensured that humanitarian agencies provide detailed budgetary information in their proposals and used this to conduct value for money analysis as per DFID’s humanitarian funding guidelines. Value for money and other information is included in Intervention Review Sheets for each intervention. In addition, we have used the lessons learnt from previous crises to help inform funding decisions. 2. Accountable grants We work particularly closely with partners receiving funding through accountable grants to scrutinise budgets and project plans to ensure that value for money considerations are being effectively addressed. 3. Direct DFID procurement Where goods and services have been procured directly by DFID, value for money is obtained through the CHASE-OT contracting process and that of allied elements (eg Air Service). The Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI), the independent body responsible for the scrutiny of UK aid has indicated its intentions to carry out a VfM assessment of emergency response to crises such as Libya. ICAI is focused on delivery of VfM for the UK taxpayer and maximising the impact and effectiveness of the UK aid budget. They have a remit to scrutinise and evaluate all ODA spend. Commercial case Direct procurement A. Procurement and commercial requirements for intervention Direct procurement is through the CHASE-OT contract and other existing and competitively tendered contracts (e.g. Air Services). £5.1 million will be spent on direct procurement. B. How does the intervention use competition to drive commercial advantage for DFID? Given the need for time critical rapid intervention, organising a competitive procurement process is not an option during a humanitarian response. In order to ensure a rapid humanitarian response DFID has arranged service contracts with partners, including Crown Agents and Air Partners. They were both selected through open competition processes. C. How do we expect the market place will respond? There is a competitive market for these types of services and DFID ensures that our service contracts and pre-qualifying arrangements offer value for money and are open to competition when the contracts come up for renewal. D. What are the key cost elements that affect overall price? How is value added and how will we measure and improve this? Logistics can account for as much as 80% of the effort of humanitarian organisations during relief operations. (HERR, page 37) DFID is commissioning a study into the main cost drivers in order to establish a baseline and work on improving this. E. What is the intended procurement process to support contract award? Service contracts are in place with partners where direct procurement was used. F. How will contract and supplier performance be managed? The performance of partners is being managed through the existing service contracts where direct procurement was used. Indirect procurement A. Why is the proposed funding mechanism/form of arrangement the right one for this intervention, with this development partner? Indirect procurement will account for £13.3 million. Choice of development partners for the Libya response For further information on value for money provided for each agency (including Multilateral Aid Review “MAR” results), please see section D of the appraisal case. IOM – IOM has a clear role to support migration management and to help prevent this from causing a humanitarian crisis. Although the MAR rated the IOM as weak overall, it also noted that it had largely good results on delivery against project targets, which was key to its work of coordinating repatriations of third country nationals from the Libyan border, and evacuations from Misrata. UNHCR – UNHCR has a clear mandate and experience of providing assistance to displaced persons. UNHCR’s experience in supporting air operations was more limited. Given this relative inexperience there is a compelling case for DFID to provide additional capacity support which we did with the secondment of three air operations advisors. ICRC - As set out above, the MAR gave the ICRC a ‘very strong’ rating for their value for money. ICRC was well placed to deal with the issue of limited humanitarian access to areas of Libya during the crisis, as it has experience of dealing with such challenges and also had strong links with the Libyan Red Crescent, one of the few humanitarian agencies with an established presence on the ground. UNICEF –The UNICEF proposal to ship goods to Misrata was a specific proposal to meet identified needs in a critical area of concern. WHO – WHO was in a unique position in Libya because it had a positive relationship with the authorities on both sides of the conflict, making it well placed to perform a coordination role and to assess humanitarian needs, particularly in the health sector. For example, WHO worked closely with the local authorities in Misrata when this city was under siege, and DFID was able to provide specific support to WHO to meet identified needs. IMC - IMC were already on the ground meeting critical medical needs in Libya. They had the capacity and willingness to scale up. MAG - MAG is a globally recognised agency with an excellent track record for mine/UXO clearance and with a clear expertise in awareness campaigns which provide essential safety to local populations. UNMAS - UNMAS is located in the United Nations Department of Peacekeeping Operations. It is responsible for ensuring an effective, proactive and coordinated UN response to landmines and explosive remnants of war through collaboration with 13 other UN departments, agencies, funds and programmes, as well as other humanitarian agencies and the private sector. Funding arrangements in place for the Libya response To formalise arrangements with partner governments and multilateral organisations DFID normally signs a Memorandum of Understanding (“MoU”) or an equivalent non-legally binding formal exchange. With a number of multilaterals, DFID has signed a formal exchange called a Framework Arrangement (“FA”). For arrangements with “not for profit” (“NfP”) organisations, Accountable Grant (“AG”) letters are drawn up. This is a funding mechanism used to fund specific, focussed, project activities with NfP organisations, for example to non-governmental organisations (“NGOs”), civil society organisations (“CSOs”) or universities. The AG includes coverage on Fraud & Corruption, Security, Intellectual Property Rights and UKaid Branding, plus a record asset / inventory management. The following arrangements have been put in place for the Libya response: IOM: Funding was through an MoU arrangement – allowing quick release of funding to support the evacuation. We also provided in-kind support to IOM by chartering flights through our contract with Air Partners. UNHCR: We have a DFID/UNHCR Global Standby Arrangement. On this occasion, DFID provided in-kind support (shelter items and secondment of three air operation specialists). ICRC: DFID has a standard MoU developed with ICRC to allow quick release of funds to replenish emergency funds ICRC has drawn down on. UNICEF: Overarching Framework Arrangement is in place so it was possible to provide funding quickly through a Contribution Arrangement. WHO: MoU has been drawn up. MAG and IMC: Accountable Grants were set up for NGOs and there was agreement for funds to be provided in advance and to facilitate swift operations. UNMAS: An MoU is being finalised with UNMAS. B. Value for money through procurement Please see section D in the appraisal case above. Financial case A. What are the costs, how are they profiled and how will you ensure accurate forecasting? Profiling: Component WHO 2022339-101 Deployment 202339-102 of Budget (£) 400,000 hum teams 920,000 UNHCR (shelter) 2022339–103 1,480,000 ICRC 202339-104 2,000,000 UNICEF 202339-105 130,000 UNHCR air operations 202339- 105,000 106 IOM 202339-107 8,600,000 IMC 202339-108 500,000 MAG 202339-109 182,216 + 585,779 (cost extension) Deployments 202339-110 776,751 ICRC 202339-111 3,000,000 UNMAS 202339-112 500,000 Total 18.4 million As this was a crisis response, it was not possible to predict ahead of time what needs on the ground would be. Once commitments had been made, we were able to forecast well. Forecasting was simplified by the fact that the nature of the response meant that most payments were appropriately made in one tranche rather than a number of instalments. B. Funding the proposal DFID staff are funded by the admin budget, from existing budgets. The funding for interventions comes from programme resources. There are two budget centres associated with the funding, CHASE budget centre P0138 and Libya Humanitarian P0362. C. Payment of funds For funding via multilateral organisations payment arrangements are set out clearly in Framework Arrangements – for those agencies with whom no such prior agreement exists, MoUs have been set up. Accountable Grant arrangements have been agreed with the two NGOs we are funding (MAG and IMC) including payment details. Since many NGOs do not hold large funding reserves, DFID has secured HM Treasury approval to pay advances to NGOs for up to three months. IMC and MAG provided letters of justification explaining why the advance payment was necessary and these requests were approved. D. Assessment of financial risk and fraud For direct procurement, financial risk and fraud is dealt with in the CHASE-OT contracting process and that of the allied elements (e.g. Air Service). For contributions to partner organisations, DFID will rely on DFID programme staff analysis of partner financial and narrative reporting as well as the monitoring, reporting and anti-fraud policies and systems of trusted partners. E. How will expenditure be monitored, reported, and accounted for? Audit, accounting and monitoring arrangements have been clearly specified in each MOU and Accountable Grant. We have requested mid term activities and finance reports and maintain continuous dialogue with agencies and donors (at the Field and HQ level) to monitor progress. Final reports are requested within three months of the project completion. Where possible we have opted to provide funding in tranches and future payments are conditional. DFID requires partners to provide a copy of their certified Annual Audited Accounts (AAA) and that they clearly show DFID funding as a distinct line of income. Management case A. Management arrangements for implementing the intervention Management of the programme will be through DFID Libya Crisis Unit. This includes a range of advisory and admin support. Primary stakeholders include the operational agencies (UN, ICRC and NGOs), beneficiaries and other donors. Contacts with operational agencies will inform DFID’s overall picture of the evolving response. B. Risks and how these will be managed Risk Mitigation Rating Probability/Impact 1. Humanitarian crisis worsens. Close liaison with humanitarian agencies to ensure that sufficient contingency plans are in place. DFID ready to respond should more support be needed. High/Medium High 2. Conflict worsens. Constant monitoring to manage impact as needs arise. High/Medium High 3. Lack of humanitarian access in parts of Libya, leaving protection needs unmet. High High 4. Outflow of refugees to borders, particularly Tunisia, sees host countries close borders/camps overwhelmed. International lobbying for humanitarian access. DFID prepared to support ICRC and other mandated partners work to meet protection needs. Humanitarian diplomacy to keep borders open and support to partners to provide for camp capacity. Humanitarian actors provide support to areas in need where access allows. Medium/low High 5. Insufficient capacity of organisations to scale up quickly and with appropriate staff. Close liaison with humanitarian agencies to ensure capacity and appropriate contingency are in place. Medium High C. Conditions that apply (for financial aid only) Not applicable. D. How will progress and results be monitored, measured and evaluated? Measurement At project set-up, a logframe is prepared for each arrangement which sets out the impact, outcome, outputs and inputs expected for the project, showing targets, milestones and baselines where available for each. The project is then designed in a way which allows measurement of these indicators, for example numbers of medical consultations delivered, or sites cleared of explosive remnants of war. In a humanitarian crisis situation it can be difficult to gather accurate data on impact, so logframes are designed to capture the data that is possible to measure. Monitoring Specific reporting requirements are covered in the: (i) MoUs with IOM, ICRC, UNHCR, WHO and UNMAS; (ii) Contribution Arrangement with UNICEF; (iii) Accountable Grants with MAG and IMC; and (iv) the service contracts in place with Crown Agents and Air Partners. Reporting requirements include monthly/quarterly reporting of progress towards logframe targets, quarterly/mid-term financial and progress reporting, and a final financial and progress report within three months of the closure of the project. Reporting requirements are agreed in line with DFID guidelines on humanitarian funding. DFID London-based staff are responsible for monitoring reporting provided by partners. Information from reports is complemented by situation reports from partner agencies, media reports and frequent dialogue with funded partners. Where the security situation permits, our field teams on the ground also monitor progress and liaise with project partners if any concerns arise. The DFID Senior Representative in Tripoli and the Libya Unit in London will retain oversight for ongoing funded programmes (WHO, UNMAS, MAG and ICRC). Evaluation Following the receipt of a project’s final report, DFID staff complete a File Closing Note which records and evaluates the success of the project against the results and impact expected and assesses its value for money. In the year following the end of the project, we also check project/partner audit reports. Humanitarian assistance to Libya is in accordance with DFID corporate procedures and could be subject to an Independent Commission for Aid Impact evaluation. At this point in time, taking into account all relevant circumstances (including the amounts involved and the level of scrutiny of humanitarian spend throughout) an evaluation visit to Libya is not planned but we will keep this under review. E. Logframe Quest number of logframe for this intervention: 3327857 Annex 1: List of Abbreviations Used DFID: UK Department for International Development HERR: Humanitarian Emergency Response Review HMG: Her Majesty’s Government ICRC: International Committee of the Red Cross IDP: Internally Displaced Person IMC: International Medical Corps IOM: International Organisation for Migration JMACT: Joint Mine Action Coordination Team MAG: Mines Action Group MAR: Multilateral Aid Review NTC: National Transitional Council OCHA: UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs TCN: Third Country National UN: United Nations UNHCR: UN Refugee Agency. UNICEF: UN Children’s Fund UNMAS: UN Mine Action Service UNSCR: UN Security Council Resolution UXO: Unexploded Ordnance WHO: World Health Organisation Annex 2: Full Environmental Assessment The table below scores the DFID intervention for its climate/environment risks and impacts, and opportunities. the quality of evidence for each option is rated as either Strong, Medium or Limited, the likely impact on climate change and environment is categorised as A, high potential risk / opportunity; B, medium / manageable potential risk / opportunity; C, low / no risk / opportunity; or D, core contribution to a multilateral organisation. Climate and Environment Assessment Scoring Table Option Evidence Rating 1 Provide humanitarian Medium assistance Limited 2 Do not intervene Climate change and environment risks and impacts, Category (A, B, C, D) C Climate change and environment opportunities, Category (A, B, C, D) C B C Option 1 scores C because our assistance was channelled through a series of multilateral organisations and on reviewing their procedures these were found sufficient for the humanitarian context this programme is working within. However, in time, there will be need for a more thorough review of how these procedures are applied in such situations. Some of the specific climate and environment issues identified include: Climate/environment issues associated with assistance provided to address protection from violence The evacuation of Third Country Nationals (TCN) was conducted by air. This was the only viable option as the emergency situation necessitated expediency. More people could be moved much faster in this way than any other means, meaning also that logistical problems – including any health, hygiene and sanitation issues associated with build up of people were avoided at border areas. DFID also ensured that larger groups of people from the same country were repatriated at the same time, thus reducing the number of flights taken. With regard to reducing the risks to people from explosive remnants of war, there are also risks to human health, biodiversity and other natural resources (e.g. soils/land) posed by the toxic substances that are associated with such remnants. The Mines Advisory Group responsible for this work has a policy of minimising environmental impact from clearance by ensuring that environmental impacts are addressed in detailed clearance plans. The Mines Advisory Group has stated that standards and learning from other programmes on environmental management will be used in Libya. Climate/environment issues associated with assistance for survival DFID has provided support through a series of our multilateral partners for immediate humanitarian needs (UNICEF, ICRC, WHO, IMC and UNHCR). DFID, through its strategic engagements with these agencies, is working with all agencies to ensure that there is adequate environmental awareness and a proportionate response to potential environment impacts in humanitarian situations. All these partners hold climate and environment policies and procedures and have some experience of applying these in humanitarian situations. Activities funded under this programme,that have a bearing on climate/environment, include providing essential drugs, medical supplies and equipment to strengthen health care and emergency treatment facilities. Other environment impacts are associated with provision of water supplies, which will be largely positive environmental impacts from a human health perspective, but depending on means of installation and technologies adopted can have some implications for the environment. We have to assume that these policies and procedures were applied as appropriate by our multilateral partners in Libya. However, when the opportunity arises it would be worth investigating how these climate/environment policies and procedures were applied, with view to identifying any lessons learnt for the future. DFID Partner Environmental Policies International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) operates within the Framework for Environmental Management in Assistance Programmes (FEMAP) which was approved in December 2009 and provides detailed guidance on the environment and how to manage environmental impacts. The Multilateral Aid Review (MAR) suggests that while there are guidelines, the extent of implementation still remains unclear. DFID is working with ICRC at an organisational level to understand how FEMAP is being applied, what environmental issues arise from its interventions, and how they are being addressed. ICRC has made a commitment to the Sphere standards (a set of internationally recognised Minimum Standards for Disaster Response), to ensure appropriate levels of service to reduce the environmental impact by displaced populations, and to minimise environmental health outbreaks. World Health Organisation (WHO): has published guidelines for safe disposal of unwanted pharmaceuticals in and after emergencies. A number of methods for safe disposal of pharmaceuticals are described, which involve minimal risks to public health and the environment. Pharmaceuticals are ideally disposed of by high temperature (i.e. above 1,200ºC) incineration. International Medical Corps (IMC): environmental aspects are taken into consideration at each of IMC’s interventions. This is in particular with regards to provision of health services – attention is paid in particular to cleanliness of the place, availability of running water, access to toilets for male and female, respecting the protocols for dealing with body fluids, disposables, used medical items and tools, as well as medical waste. In Misrata major challenges are reported regarding sanitation and the availability of clean water. IMC undertakes to provide as much support to environmental and sanitation requirements as is possible in this environment. UNICEF all programmes and projects have to complete an environmental impact assessment (EIA). UNHCR recognizes the potential damage that camps and settlements can have on the environment, as well as on the local economy and relations with host communities. To this end, the refugee agency has developed an overarching policy to deal with environmental issues. Equally important, UNHCR develops and supports a range of field projects that help reduce or overcome some of the damage caused by humanitarian operations. UNHCR also responds to new, emerging threats such as climate change.