View/Open

advertisement

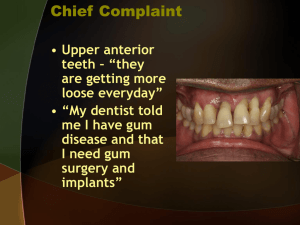

Treatment of aggressive periodontitis For figures, tables and references we refer the reader to the original paper. Aggressive periodontitis comprises a group of rapidly progressing forms of periodontal disease that occur in otherwise clinically healthy individuals. It is accepted that, compared with patients with chronic periodontitis, patients with aggressive periodontitis show a more rapid attachment loss and bone destruction that occurs earlier in life. The patient's age when attachment loss is detected is often the criterion used by clinicians to diagnose aggressive periodontitis and to distinguish aggressive periodontitis from chronic adult periodontitis [reviewed by Albandar in this volume of Periodontology 2000 [3]]. Typically, aggressive periodontitis runs in families (familial aggregation), pointing towards a genetic predisposition. These three features (i.e. rapid attachment loss, bone destruction that occurs early in life and familial aggregation) are considered to be the primary features of this disease. In the Workshop for a Classification of Periodontal Diseases and Conditions, the secondary features of aggressive periodontitis were identified as (i) relatively low amounts of bacterial deposits despite severe periodontal destruction, (ii) presence of hyper-responsive macrophage phenotypes, and (iii) increased portions of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans and Porphy-romonas gingivalis [46]. Recently an entire volume of Periodontology 2000 was devoted to the differences in clinical [5] and histopathological [93] features, epidemiological patterns [24], microbiological [4] and immunological [29, 81] aspects, and genetic and environmental risk factors [94] between aggressive periodontitis and chronic periodontitis. From these reviews it becomes clear that there are indeed major differences between aggressive periodontitis and chronic periodontitis. Despite these major differences, it is not always easy to differentiate these two disease entities clinically. However, from a research perspective, it is essential that these diseases can be, and are, clearly distinguished in order to gain a complete understanding of their etiology and pathogenesis [5]. Also, as pointed out throughout this review, from a treatment perspective, distinction is of major importance. Additionally, patients with aggressive periodontitis are often diagnosed as having a localized form or a generalized form of disease. Each form has its own typical clinical features. The relative lack of clinical inflammation, often associated with the localized molar-and-incisor form of aggressive periodontitis, has been recognized for almost 100 years. It is generally accepted that this form of the disease is most often associated with a thin biofilm, at least in its early stages. In contrast, the presence of clinical inflammation in generalized aggressive periodontitis appears to be similar to that observed in chronic periodontitis. In this situation, age of onset and familial aggregation are important additional criteria for either diagnosis or classification. It is also becoming more commonly recognized that chronic periodontitis may occur simultaneously with both localized and generalized forms of aggressive periodontitis (reviewed in reference [5]). The overall treatment concepts and goals in patients with aggressive periodontitis are not markedly different from those in patients with chronic periodontitis. Therefore, the different treatment phases (systemic, initial, re-evaluation, surgical, maintenance and restorative) are similar for both types of periodontitis. However, the considerable amount of bone loss relative to the young age of the patient and the high rate of bone loss warrants a well-thought-through treatment plan and an often more aggressive treatment approach, in order to halt further periodontal destruction and regain as much periodontal attachment as possible. The ultimate goal of treatment is to create a clinical condition that is conducive to retaining as many teeth as possible for as long as possible. Diagnosis and treatment planning Given the rapid progression of the disease and the high degree of difficulty in gaining control of the disease, diagnosis and treatment of aggressive periodontitis should preferably be carried out by a periodontist. However, the general practitioner does play an essential role in the early detection of patients who potentially have aggressive periodontitis. For a proper diagnosis, a thorough review of the patients' medical history, medications, family history and social history is required. In addition to an anamnesis, screening tests can be performed to establish systemic modifying factors such as diabetes and hematological conditions. Should a systemic disease be present, for instance poorly controlled diabetes, specialist medical consultation should be sought. Furthermore, risk factors, such as smoking and stress, must be identified. The diagnosis should be made based on the above-mentioned criteria and considerations, together with a thorough mapping of the periodontal condition, which includes the recording of probing pocket depths, clinical attachment levels, bleeding on probing, furcation involvement, suppuration and tooth mobility, and an assessment of the patients' level of oral hygiene. These data, together with a radiological analysis, are of utmost importance for screening and for establishing the proper diagnosis and a differential diagnosis. The diagnosis will also be a clear starting point for proper treatment planning, for evaluating and explaining treatment effects to the patient and for patient education. It is important to realize that even the most aggressive and advanced cases of periodontitis are treatable. Case reports have been published with a follow-up of up to 19 years for patients with localized aggressive periodontitis [65] and a follow-up of up to 40 years for patients with generalized aggressive periodontitis [67]. However, it is essential for the patient to be highly compliant and highly motivated to do his part in order to gain control of the disease. A concerted effort must therefore be made by the clinician to inform the patient about the severity of the disease and the risk factors, and the role of the patient in the treatment. Also, the patient must be instructed very precisely about the necessary oral-hygiene measures. Furthermore, the clinician must assist the patient in controlling risk factors, such as smoking. Considerable evidence points to a familial aggregation of aggressive periodontitis [discussed by Vieira & Albandar in this volume of Periodontology 2000 [104]]. Therefore, it is the practitioners' duty to inform the patient of this aspect and at least suggest screening other family members once the diagnosis has been established. The patient should be asked about the periodontal condition of their close relatives and, if possible, these relatives should seek consultation with a periodontist [11, 66]. Initial phase Treatment of aggressive periodontitis starts with patient education and ensuring patient compliance. A considerable amount of time should be invested in establishing a good patient–clinician relationship. The time devoted to this, before commencing any form of active treatment and during the whole process of periodontal therapy, will have an impact on treatment success that should not be underestimated. The patient should be clearly informed about the disease process, contributing factors, the different phases and goals of the treatment, the predictability of treatment success and the patient's own crucial role in the treatment. The patient should be aware that, for success, it is essential for optimal compliance in plaque control and maintenance and for possible modifiable risk factors to be addressed. If the clinician doubts the compliance of the patient, several pretreatment visits could be included in the treatment plan, in which compliance with oral-hygiene instructions can be monitored and enhanced, together with compliance towards, for example, a smoking-cessation protocol. Owing to the aggressive nature of the disease, clinicians are often faced with teeth that are severely periodontally compromised. The prognosis of these teeth needs to be discussed with the patient when setting up a treatment plan [8]. One of the most difficult aspects is whether or not to extract a tooth. It is often stated that retention of hopeless teeth, but also of teeth with a doubtful prognosis, can compromise the treatment outcome. Leaving residual pockets of ≥6 mm is a risk factor for the progression of periodontal disease after active treatment [57]. Residual deep pockets are niches in the mouth where considerable numbers of pathogenic bacteria can remain, even after treatment. Earlier studies have reported the disappearance of pathogenic bacteria from the mouth after extraction of compromised teeth, thus preventing recolonization of other teeth [19]. A protective effect of extracting such compromised teeth has been identified in young children [78]. It is therefore suggested that a more radical extraction protocol is justified when treating patients with aggressive periodontitis. However, the use of high-sensitivity bacterial-detection techniques has indicated that even after a full-mouth tooth extraction, periodontal pathogens remain in the mouth. Van Assche et al. [100] performed a full-mouth tooth extraction in nine patients and took microbial samples of subgingival plaque, the tongue dorsum and the saliva before extraction, and samples of the tongue dorsum and the saliva 6 months after extraction. Using a quantitative PCR analysis, the authors showed that, although tooth extraction resulted in significant reductions in the numbers of periodontal pathogens, it failed to eliminate the pathogenic species from the mouth [100]. A study by the same authors investigated the microbial ecology in the newly formed pockets around implants placed in patients 3–6 months after a full-mouth tooth extraction. They showed that as soon as 1 week after abutment connection, the detection frequencies of pathogenic bacteria around the newly placed implants had risen to detection frequencies comparable with those before extraction. The bacterial numbers, however, were lower than before extraction [77]. As a full-mouth extraction of periodontally compromised teeth does not result in the elimination of pathogens from the mouth, the extraction of compromised teeth in the dentate patient will probably not result in sufficient protection from recolonization around other teeth. Thus, extraction of teeth should not be advocated for preventing colonization around other teeth in the mouth. Although the ultimate goal in the treatment of aggressive periodontitis is to create a clinical condition that is conducive to retaining as many teeth as possible for as long as possible, this is obviously difficult because patients with aggressive periodontitis are considerably younger than the average patient with chronic periodontitis. This age aspect interferes with treatment and treatment planning at different levels, some of which are not often considered. One level is the psychological impact of the message that multiple teeth need to be extracted in young patients. Whilst there are currently no studies that address this aspect in patients with aggressive periodontitis, there are some indications that the impact of tooth loss on people and their lives should not be underestimated. Davis et al. [20] reported that in a cohort of 94 fully edentulous patients, 45% reported retrospectively to have experienced difficulties in accepting their tooth loss. In the cohort of Naik & Pay [66], which comprised 400 fully and partially edentulous patients, ‘only’ 25% of the patients reported having difficulties in accepting the loss of their teeth. One of the major differences between both studies was the age of the patients, which was above 60 years in the study by Naik & Pay [66] but of a wider range (31 years and older) in the study by Davis et al. [20]. It cannot be directly derived from the latter paper whether younger patients experience more coping problems than do older patients, but it could be a reasonable hypothesis. Additionally, one should take into account that the patient's attitude toward tooth loss might be different in different parts of the world. Similarly, one could hypothesize that the compromised esthetics after periodontal therapy might have a significant effect on the general and psychological well-being, self-esteem and daily social life of younger patients. Another level on which age impacts treatment in aggressive periodontitis is the prosthetic rehabilitation. Obviously, when teeth are extracted, the patient will seek adequate prosthetic rehabilitation. Although teeth can have a life expectancy of over 80 years, there is currently no single type of prosthetic device with a similar life expectancy. This means that the age of the patient when a tooth/teeth are extracted can play a decisive role in the patient's quality of life. Early extraction of a putatively questionable tooth in a 40-year-old patient with a life expectancy of 80 years could mean the start of time-consuming and expensive prosthetic treatment for the next 40 years [30, 51, 74]. However, when considering that several studies have demonstrated that compromised teeth can survive for decades, given that a proper maintenance program is followed. In this regard, Graetz et al. [30] followed 34 patients with aggressive periodontitis and 34 patients with chronic periodontitis, who had two or more teeth with alveolar bone loss of ≥50%, for 15 years. After 15 years they found that in the patients with aggressive periodontitis, 88.2% of the teeth with a questionable prognosis and 59.5% of the teeth with a hopeless prognosis had survived [30]. These authors did not find any significant difference in tooth-survival rate between patients with aggressive periodontitis and patients with chronic periodontitis. It has been suggested that teeth with a predicted questionable prognosis as a result of severe bone loss should not be treated periodontally, but rather extracted early to avoid possible involvement of neighboring teeth. In regard to this aspect, it has been shown that long-term preservation of hopeless teeth is an attainable goal with no detrimental effect on the adjacent teeth [53]. The treatment of periodontally compromised teeth that have advanced bone loss is a meaningful, therapeutic approach to prevent tooth loss with the consequence of prosthetic rehabilitation. Several studies have been performed in which the prognosis of dental implants in periodontally healthy subjects has been compared with the prognosis of dental implants in subjects with aggressive periodontitis. De Boever et al. [21] placed implants in, and followed up, 110 patients. Sixty-eight of these patients had suffered from chronic periodontitis and 16 from generalized aggressive periodontitis. After a follow-up period of 100 months in which the patients were enrolled in a maintenance program, there was a significant difference in implant survival between the chronic periodontitis and generalized aggressive periodontitis groups, with implant-survival rates of 96% and 80%, respectively [21]. Swierkot et al. [96] evaluated the prevalence of mucositis and peri-implantitis, implant success and implant survival in patients treated for generalized aggressive periodontitis, over a period of 5–16 years, comparing them with periodontally healthy subjects. They found that patients with generalized aggressive periodontitis had a five times greater risk of implant failure, a three times higher risk of developing mucositis and a 14 times greater risk of developing periimplantitis [96]. Similarly to these studies, Mengel & Floris-de-Jacoby [60] studied 39 patients over a 3-year period following implant placement: 15 patients were treated for generalized aggressive periodontitis, 12 for chronic periodontitis and 12 patients were periodontally healthy. The results showed that the increase in pocket depth and attachment loss was greater, and the implant-survival rate was lower, for subjects with generalized aggressive periodontitis than for periodontally healthy subjects or patients with chronic periodontitis [60]. From the aforementioned studies it can be concluded that implant survival in patients with generalized aggressive periodontitis is lower than in periodontally healthy subjects, or even in patients with chronic periodontitis. For localized aggressive periodontitis specifically there is very little evidence on which to base any conclusions. Clinicians should be aware of this when they consider implant-supported restorations for replacing teeth in patients with aggressive periodontitis, especially as patients with aggressive periodontitis are generally of a younger age than are patients with chronic periodontitis. This means that dental restorations need to remain functional and retain good esthetics for a longer period of time in these patients. Consulting with other dental specialists to assess the strategic restorative value of certain teeth or to assess alternative restorative options, such as orthodontic treatment, might help in the final decision of whether to extract or to retain. Active periodontal treatment Despite better insights into the etiology of aggressive forms of periodontitis, initial treatment is directed toward the bacterial load in the periodontal pockets. As such, there is no difference between the treatment concepts used for treating chronic periodontitis or aggressive periodontitis. However, the clinical response to nonsurgical therapy is much less documented for aggressive periodontitis than for chronic periodontitis. The number of studies assessing the effect of periodontal treatment on aggressive periodontitis is limited and they often report on only a small number of patients. This primarily relates to the low prevalence of this disease, and this hampers the execution of comparative clinical trials. Nonsurgical therapy Although the effect of nonsurgical treatment on chronic periodontitis is well documented [39], its effect on aggressive periodontitis is much less clear. In relation to the effect of nonsurgical therapy alone as a treatment for aggressive periodontitis, two aspects seem of importance. The first aspect relates to the question of whether, and to what extent, scaling and root planing alone can result in the desired clinical changes, such as probing pocket-depth reduction, gain in clinical attachment and reduction in bleeding on probing. Ideally, this aspect is derived from data on the magnitude of the effect on the clinical parameters (e.g. the amount of probing pocket-depth reduction) combined with data on the predictability (e.g. the proportion of patients responding to treatment). Unfortunately, the latter is often not reported. The second aspect relates to the long-term stability of the results obtained. For this, longitudinal data are necessary. For localized aggressive periodontitis, the effect of nonsurgical therapy alone can be derived from studies in which scaling and root planing represent the first phase of a staged combination therapy. In this regard, Slots & Rosling [92], evaluated 20 deep pockets in six patients with localized aggressive periodontitis and reported a small reduction of 0.3 mm in the probing pocket depth 16 weeks after scaling and root planing. However, this reduction was accompanied by a small average loss, of 0.05 mm, in clinical attachment. Similarly to these observations, Kornman & Robertson [44] reported an average probing pocket-depth reduction of 0.1 mm in eight patients, 2 months after scaling and root planing. This virtual absence of clinical response is, however, contradicted by data from comparative studies in which scaling and root planing alone represented the control treatment of the study. Reporting on 19 patients with localized aggressive periodontitis, Palmer et al. [72] showed an average reduction of approximately 0.8 mm in probing pocket depth and an average gain in clinical attachment of approximately 0.3 mm for the affected teeth, 3 months after scaling and root planing. Also, a reduction in bleeding on probing was observed. Asikainen et al. [6] even reported an average probing pocket-depth reduction of 1.4 mm in eight patients, 2 months after scaling and root planing. Unfortunately, none of the above-mentioned studies performed a statistical analysis of the observed effects. However, Ünsal et al. [99] analyzed the clinical effect of scaling and root planing alone in nine patients with localized aggressive periodontitis included in the control group of their study. Three months after performing scaling and root planing, pocket-depth reduction of 1.8 mm and clinical attachment gain of 1.2 mm was recorded. These effects were accompanied by a significant reduction in bleeding on probing, from 47.1% to 10.1%. Although the average probing pocket depth was not provided by Saxén et al. [83], it is interesting to note that the four patients with localized aggressive periodontitis in the control group of the study who did not receive surgery, showed a significant reduction in the percentage of sites with a probing pocket depth of >4 mm, from 19.4% at baseline to 2.8% 20 months after scaling and root planing. These findings are in line with those reported by Gunsolley et al. [35], who recalled 19 treated and 21 untreated patients with localized aggressive periodontitis, approximately 4 years after initial therapy. Some of the treated patients also received open flap curettage but, according to the authors, there was no significant difference in response between both groups of treated patients. Although no statistical comparison between the baseline and the recall data (approximately 4 years after baseline) was performed, the clinical data show, for the treated patients, a reduction in probing pocket depth of 0.2 mm and a gain in clinical attachment of 0.3 mm. Interestingly, probing pocket depth was increased by an average of 0.2 mm, and an additional loss of attachment of 0.3 mm was recorded for the untreated patients with localized aggressive periodontitis. These limited data and statistical analyses on the effect of scaling and root planing in patients with localized aggressive periodontitis hamper a solid conclusion on its effectiveness and long-term stability. However, based on these data, it seems that scaling and root planing improves the clinical parameters in patients with localized aggressive periodontitis, which contradicts the reports from the 1980s. Its predictability is unknown, but the clinical effects can be recorded for up to 3 years after treatment. The effect of root planing alone on generalized aggressive periodontitis is much better documented, although only one study has been specifically designed to assess the effect on clinical parameters. Hughes et al. [38] re-evaluated 79 patients with generalized aggressive periodontitis, 10 weeks after scaling and root planing. They reported statistically significant mean changes in overall probing pocket depth of 0.4 ± 1.7 mm, and of 2.1 ± 2.0 mm for initially deep pockets. An overall gain in clinical attachment of 0.2 ± 1.93 mm was also recorded, and for deep sites this was 1.77 ± 2.15 mm. The percentage of bleeding on probing was reduced by 34%. Interestingly, the authors reported that 32% of the patients did not respond to treatment. Probably, this large proportion of nonresponders can explain the large standard deviation values observed in this study. The nonresponding patients were primarily smokers. The observation that scaling and root planing indeed reduces clinical probing pocket depth and bleeding on probing, and results in a gain of attachment, is also confirmed by several comparative studies investigating the adjunctive effect of antimicrobials where the control group was treated with scaling and root planing alone [1, 7, 12, 34, 36, 37, 62, 76, 82, 88, 103, 106, 107] (Table 1). These studies show average whole-mouth probing pocket-depth reductions ranging from 0.7 to 1.5 mm, and average gains in clinical attachment ranging from 0.2 to 1.4 mm. For the majority of these studies the clinical changes were statistically significant. These results confirm the effectiveness of scaling and root planing in patients with generalized aggressive periodontitis, at least for the short term. In most of these studies the outcome of scaling and root planing was assessed, for the first time, 2–6 months after the baseline measurements had been performed. However, some studies followed the clinical results over time, up to 24 months after scaling and root planing, and the data from these studies can provide important information on the stability of the clinical results obtained. The majority of these studies show that the probing pocket-depth reductions [1, 12, 36, 37, 88, 103, 107] and gains in clinical attachment [1, 12, 34, 36, 37, 88, 103] remain stable or improve, up to 6 months after the initial therapy (Table 1). However, in some studies, there is already a small relapse in probing pocket-depth reduction [34, 82, 106] or a gain in clinical attachment [82, 106, 107] between 3 and 6 months after scaling and root planing. Studies with longer follow-up [36, 88] show that after 6 months, probing pocket depths start to increase and the obtained gain in clinical attachment starts to decrease (Table 1). These findings are again in agreement with those reported by Gunsolley et al. [35] who recalled 28 treated and 20 untreated patients with generalized aggressive periodontitis, approximately 4 years after initial therapy. Although no statistical comparison was performed between the baseline data and the recall data, the clinical data show an increase in probing pocket depth of 0.3 mm and a loss in clinical attachment of 0.4 mm for the treated patients. Based on these observations, it seems that generalized aggressive periodontitis responds well to scaling and root planing in the short term (up to 6 months). However, after 6 months, relapse and disease progression is reported, despite frequent recall visits and oral-hygiene reinforcements. Systemic antibiotics Treating patients with aggressive periodontitis is challenging. The disease responds less predictably to conventional mechanical periodontal therapy than chronic periodontitis [11, 90], the disease progression is rapid and severe and patients are generally of a younger age. Hence, scientists and clinicians have been exploring adjunctive treatments to enhance the outcome, stability and predictability of conventional mechanical therapy. In view of the specific microbiological nature of both types of aggressive periodontitis, the use of chemotherapeutics and, more specifically, of systemic antibiotics, could play an important role in the treatment of these diseases. Although it is currently well established that antibiotics should not be administered without prior disruption of the bacterial biofilm [64], at least two studies have evaluated the effect of systemic antibiotics as the sole form of therapy in patients with localized aggressive periodontitis [17, 69, 70]. These studies show that tetracycline, systemically administered over a period of at least 6 weeks, in combination with supragingival plaque control, decreased the probing pocket depths and resulted in gains in clinical attachment for up to at least 24 months. In addition, this regimen may lead to some repair of the alveolar bone defects. These data were largely confirmed by Slots & Rosling [92] who administered 1 g of tetracycline for 2 weeks after completion of an initial phase of scaling and root planing. The scaling and root planing reduced the total subgingival bacterial counts and the proportions of certain gram-negative bacteria, but no periodontal pocket became free of A. actinomycetemcomitans, and the study reported small clinical changes after debridement. However, the administration of tetracycline, 6 weeks following scaling and root planing, and in the absence of a new phase of instrumentation, resulted in a gain in clinical attachment level of 0.27 ± 0.45 mm and suppression of A. actinomycetemcomitans, Capnocytophaga and spirochetes to low or undetectable levels in all test periodontal pockets. Although these were important observations in relation to our understanding of aggressive periodontitis, and although they were recently confirmed in patients with chronic periodontitis using metronidazole and amoxicillin [50], newer data do not validate the treatment approach that was used in the latter study. There is currently a clear consensus that mechanical instrumentation must always precede antimicrobial therapy. One should first mechanically reduce the subgingival bacterial load, which might otherwise inhibit or degrade the antimicrobial agent. Furthermore, one should mechanically disrupt the structured bacterial aggregates that can protect the bacteria from the agent [64]. Insufficient concentrations of the active agent may favor the emergence of resistant bacterial strains. Surprisingly, little investigation has been carried out into the adjunctive effect of systemic antibiotics on the outcome of mechanical instrumentation in patients with localized aggressive periodontitis. The first reports can be traced back to the end of the 1970s [91]; however, few studies have focused specifically on localized aggressive periodontitis. It is obvious that this hampers our current understanding of the use of systemic antibiotics in the treatment of this patient group. Furthermore, the approach, in terms of the set-up of the studies, the combination of different treatments used and the way of reporting data, was markedly different in these older papers from what is now considered to be the standard. Even more importantly, the development and the exponential increase of antibiotic resistance over the past two decades should increase our awareness that the antibiotic regimens used then might no longer be as effective. It must be considered that the absence of clinical trials addressing the issue of adjunctive systemic antibiotics in the treatment of localized aggressive periodontitis does not reflect a lack of interest in this disease. However, the low prevalence of localized aggressive periodontitis makes it hard to find sufficient numbers of patients, which might be a reason for this lack of new studies. On the other hand, this lack might reflect a publication bias owing to the absence of any significant adjunctive effect of systemic antibiotics. There is therefore an urgent need for new clinical trials addressing this issue. Although the adjunctive effect of tetracycline on scaling and root planing was observed by Slots et al. in 1979 [91], the limited number of patients in the study does not allow a definitive conclusion to be reached. Kornman & Robertson [44] reported on the administration of systemic tetracycline (1 g/day for 28 days) as an adjunct to scaling and root planing, starting on the first day of scaling and root planing. It is assumed from their article that scaling and root planing was completed within the 28day period in which the patients were taking the systemic antibiotics. Although this study was not placebo controlled, the eight patients included served as their own controls because they received scaling and root planing without tetracycline 2 months before receiving scaling and root planing supplemented with systemic tetracycline. The authors concluded that scaling and root planing alone had essentially no effect on either clinical or microbiological parameters. The mean probing pocket depth was reduced from 8.0 ± 1.1 mm to 7.9 ± 1.1 mm in this study. However, when scaling and root planing was repeated in conjunction with systemic tetracycline, an additional mean reduction in probing pocket depth to 6.4 ± 1.3 mm was recorded. Despite several reports on the adjunctive use of systemic antibiotics during periodontal treatment (including surgery) of localized aggressive periodontitis [45, 56, 84], none of these studies actually evaluated the effect of antibiotics relative to scaling and root planing alone. The first actual randomized placebo-controlled study was published by Asikainen et al. in 1990 [6]. Sixteen patients were randomized into a placebo group and a group that received systemic doxycycline at a loading dose of 200 mg and doses of 100 mg daily for 14 days thereafter. All patients received scaling and root planing as part of their treatment. Scaling and root planing was performed over an 8-week period, although the systemic antibiotic or placebo was only used during the first 2 weeks of the scaling and root planing. No significant differences were found between groups in probing pocket depth and bleeding on probing, during and at the end of the study. These results encouraged the researchers to explore the effect of other systemic antibiotics. Saxén & Asikainen [83] randomized 27 patients into a placebo group, a tetracycline group (1 g/day for 12 days) and a metronidazole group (600 mg/day for 10 days). Scaling and root planing was performed at baseline and was repeated at 3 months. At 6 months postoperatively, the periodontal condition had improved in all groups. However, in the metronidazole group the percentage of pockets deeper than 4 mm was reduced more than in the other groups. Additionally, only one patient was still positive for A. actinomycetemcomitans, whereas in the tetracycline and control groups, four and six patients, respectively, were still positive for the bacterium. Whilst no statistical analysis was performed, the authors concluded that there was a higher predictability of the treatment results of scaling and root planing when the treatment was performed with adjunctive use of metronidazole than with tetracycline. In contrast to these results, Palmer et al. [72] evaluated the effect of adjunctive tetracycline (1 g/day for 14 days) in 38 patients. Scaling and root planing was performed within 7 days, and the antibiotics were administered starting from the last scaling and root planing session. Three months after baseline the improvements in probing pocket depth, clinical attachment level and bleeding on probing were significantly better in the tetracycline group. These results, in relation to the whole study, which also included a surgical phase, led the authors to conclude that systemically administered tetracycline is a useful adjunct in the nonsurgical treatment phase of localized aggressive periodontitis. However, administering the antibiotic at the surgical phase did not provide any further, statistically significant, advantage. Tinoco et al. [98] evaluated the effect of metronidazole (750 mg/day for 8 days) combined with amoxicillin (1500 mg/day for 8 days) as an adjunct to scaling and root planing in a randomized, placebo-controlled study involving 20 patients with localized aggressive periodontitis. Although 1 year after treatment, both groups showed significant clinical benefits, patients who had received systemic antibiotics adjunctively showed better results regarding probing pocket depth, clinical attachment level, gingival bleeding index and radiological bone fill. As it seems, from the above-mentioned studies, that adjunctive systemic antibiotics improve the clinical outcome in patients with localized aggressive periodontitis, the question arises of whether the type of antibiotic is of importance. This aspect was addressed by Akincibay et al. [2], who compared the clinical outcome of systemic doxycycline vs. systemic metronidazole combined with amoxicillin during scaling and root planing. They randomly divided 30 patients into two treatment groups. The first group received 100 mg of doxycycline for 10 days and the second group received 375 mg of amoxicillin and 250 mg of metronidazole three times a day for 10 days. They found that both groups showed significant improvements in plaque index, gingivitis index, periodontal probing depth and clinical attachment level values. The metronidazole plus amoxicillin group showed significantly more improvement in plaque index and gingivitis index. Although the authors reported no statistically significant differences in probing pocket depths and attachment levels between both groups at the end of the study, there was at least a clear tendency for more improvement in the metronidazole plus amoxicillin group. In contrast to localized aggressive periodontitis, the effect of systemic antibiotics as an adjunct to scaling and root planing in generalized aggressive periodontitis has been subjected to many more randomized, placebo-controlled studies. Among a variety of antibiotics that can be used and have been tested as adjuncts in generalized aggressive periodontitis, the combination of amoxicillin and metronidazole is becoming advocated to an increasing extent. The rationale behind combining both antibiotics has found its origin in the observation that A. actinomycetemcomitans was resistant to tetracycline, the antibiotic of choice in the 1990s [83, 105]. The failure of tetracycline to suppress A. actinomycetemcomitans, together with in-vitro data showing the synergistic effect of metronidazole and amoxicillin on A. actinomycetemcomitans [73] instigated van Winkelhoff et al. [101] to study the efficacy of this antibiotic combination to eliminate A. actinomycetemcomitans from subgingival sites. The combination of 250 mg of metronidazole and 375 mg of amoxicillin, three times a day for 7 days, as an adjunct to scaling and root planing, was found to be very effective in suppressing subgingival A. actinomycetemcomitans [101]. Both microbiological and clinical effectiveness of this combination therapy has been shown for patients with chronic periodontitis [86]. Recently, Sgolastra et al. [87] performed a meta-analysis of the effectiveness of the adjunctive use of amoxicillin and metronidazole in patients with generalized aggressive periodontitis and included six randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials [7, 34, 62, 103, 106, 107] published up to September 2011. The study results clearly showed an adjunctive effect of the amoxicillin–metronidazole combination in patients with generalized aggressive periodontitis. Despite the fact that the majority of the included studies individually failed to show a statistically significant effect, significant mean differences in clinical attachment gain of 0.42 mm, pocket-depth reduction of 0.58 mm, bleeding on probing changes of 14.95% and gingival bleeding changes of 21.44% were calculated in favor of the antibiotics. It is interesting to note that the mean differences for clinical attachment gain, probing pocket-depth reduction and bleeding on probing in patients with aggressive periodontitis were higher than the mean differences reported in another meta-analysis by the same authors, which investigated the adjunctive effect of the amoxicillin–metronidazole combination in patients with chronic periodontitis [86]. This may suggest that patients with generalized aggressive periodontitis benefit more from an adjunctive combination therapy than do patients with chronic periodontitis. Since September 2011, two additional randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials have largely confirmed the outcome of the meta-analysis of Sgolastra et al. [1, 12]. It should be noted that in these studies, a variety of dosages for both antibiotics were used (between 750 mg and 1500 mg/day), as were a variety of administration regimens in terms of duration (between 7 and 14 days) and how scaling and root planing was performed (see Table 1). As no comparative data are available, it is currently impossible to define a clear protocol. However, data are available on the optimal timing of the use of amoxicillin and metronidazole in relation to nonsurgical therapy. It has been suggested that patients with aggressive periodontitis should initially be treated with scaling and root planing alone and then be clinically monitored, and only in refractory cases should systemic antimicrobial therapy be used as an adjunct to re-instrumentation [91]. Thus, antimicrobials are more likely to be used at the retreatment visit rather than as part of the initial therapy [31]. Although this is a reasonable approach, it can only hold if patients who receive antibiotics at the retreatment show at least the same benefits compared with those who receive the same regimen at the initial therapy. Recently, in a retrospective study [43] as well as in a prospective study [31], it has been shown that there is a clear clinical benefit of using antibiotics at the initial therapy compared with using them at retreatment. Despite the fact that the combination of metronidazole and amoxicillin has shown additional clinical benefits beyond those of scaling and root planing alone in patients with generalized aggressive periodontitis, it is still not clear whether this combination is more effective than other antibiotics because few comparative studies have been performed. Sigusch et al. [88] compared the effects of metronidazole, clindamycin and doxycycline with a control group treated without antibiotics. It should be noted that the antibiotics were used at retreatment as an initial scaling and root planing procedure had been performed 3 weeks before re-instrumentation and antibiotic administration. The authors reported that the use of metronidazole or clindamycin was more effective in reducing probing pocket depth and gaining attachment compared with the control or the use of doxycycline, indicating the superiority of these two antibiotics. Similarly, also using a retreatment approach, 6 weeks after initial therapy, Xajigeorgiou et al. [106] assessed the effect of adjunctive use of metronidazole plus amoxicillin, metronidazole alone or doxycycline alone, compared with a control group. Presumably owing to the small number of patients in each group, no statistically significant differences could be shown. However, it is interesting to note that for probing pocket-depth reduction and clinical attachment gain, the largest additional benefit after retreatment was seen for the metronidazole alone and metronidazole plus amoxicillin groups. A smaller benefit was noted for the doxycycline group, and no benefit of retreatment was seen for the control group [106]. Similar results, albeit reaching statistical significance, were recently obtained by Baltacioglu et al. [7] when the antibiotics were administered at initial therapy. In a study comparing the effectiveness of the adjunctive use of metronidazole plus amoxicillin, doxycycline, or scaling and root planing alone, the authors found that the combination of metronidazole plus amoxicillin resulted in a significantly greater probing pocket-depth reduction and gain in clinical attachment compared with the use of doxycycline or with the control treatment. However, doxycycline also showed a statistically significant additional probing pocket-depth reduction and clinical attachment gain vs. the control. In contrast to these studies, Machtei & Younis [54] could not find differences in clinical outcome between patients receiving either metronidazole combined with amoxicillin or doxycycline as adjuncts to first-phase therapy. In their study, 24 patients with generalized aggressive periodontitis and five patients with localized aggressive periodontitis were divided over the two test groups. Patients received a quadrant-wise scaling and root planing at weekly intervals and were given oralhygiene instructions. They were placed into one of two treatment groups: 1500 mg/day of amoxicillin and 750 mg/day of metronidazole for 14 days; or a 200-mg loading dose of doxycycline followed by 100 mg of doxycycline, daily, for 30 days. During the 3-month follow-up period, patients were recalled biweekly for oral-hygiene reinforcement and motivation. The authors found that under these conditions, both regimes provided clinical improvements and that the differences in the results between both groups were not significant. However, it should be borne in mind that the duration of the doxycycline therapy was much longer than for the regimen with other antibiotics. Taking this limited number of comparative studies together, it appears that the adjunctive use of metronidazole plus amoxicillin, metronidazole alone or clindamycin in patients with generalized aggressive periodontitis results in more pronounced clinical improvements when compared with the use of doxycycline for a similar amount of time or with scaling and root planing alone. Recently, the effectiveness of azithromycin in the treatment of aggressive periodontitis was also tested. Compared with other antibiotics, azithromycin has the advantage of having a long half-life. As azithromycin only needs to be administered once a day for 3 days, one could assume that patient compliance would be better compared with other antibiotic regimens. Compliance to an adjunctive antibiotic regimen seems to be an important aspect for the clinical outcome in aggressive periodontitis. In a retrospective analysis, Guerrero et al. [33] demonstrated that incomplete adherence to a metronidazole plus amoxicillin regimen resulted in significantly less probing pocketdepth reduction and less gain in clinical attachment. Therefore, Haas et al. [36] compared the clinical effect of the adjunctive use of azithromycin with scaling and root planing in aggressive periodontitis. One year after treatment, a significant additional 1 mm reduction in probing pocket depth and 0.7 mm gain in attachment was evident, which shows the potential of azithromycin in the treatment of aggressive periodontitis. In this study, localized and generalized periodontitis patients were pooled. Local antimicrobials Although there is a clear rationale for the use of local antimicrobials, which is based on the emerging antibiotic resistance, the possibility to achieve maximum antibacterial concentrations and the reduction of systemic side effects, the effectiveness of local antimicrobials in aggressive periodontitis has barely been investigated. However, especially for localized aggressive periodontitis, the localized character and limited number of diseased sites would in theory favor their use. Surprisingly, hardly any study has investigated, in a controlled manner, the possible adjunctive effect of local antimicrobials in localized aggressive periodontitis. To the best of our knowledge, only Ünsal et al. [99] have performed a comparative study. In this study, 26 patients with localized aggressive periodontitis were randomized, after scaling and root planing, into a control group, a group receiving 1% chlorhexidine gel (subgingivally administered) and a group receiving a 40% tetracycline gel (subgingivally administered). The local subgingival administration of either of the two antimicrobial agents did not result in a significant additional improvement of the clinical parameters in these patients after the 12-week observation period. The use of local antimicrobial agents has also been tested in generalized aggressive periodontitis. However, only one study actually compared the adjunctive use of a local antimicrobial vs. scaling and root planing alone [82]. In this study, the effect of tetracycline fibers was investigated, in a split-mouth design, over a 6-month follow-up period in 10 patients with generalized aggressive periodontitis. The adjunctive use of tetracycline fibers resulted in statistically significant additional probing pocket-depth reductions of 0.6 mm and in gains of clinical attachment of 0.7 mm, up to 6 months after therapy. On the other hand, the effect of local antimicrobials has been compared with the effect of systemic antibiotics in patients with generalized aggressive periodontitis. Purucker et al. [76] compared the effect of tetracycline fibers with systemically administered amoxicillin/clavulanic acid over a 52-week period in 28 patients. Both adjuvants were applied 15 weeks after initial therapy (8 weeks after the completion of initial therapy) without additional scaling and root planing. Under these conditions, no statistically significant differences between either treatment modalities were recorded in probing pocket depth and clinical attachment level. A significant difference in bleeding on probing was recorded at week 54 in favor of the systemic antibiotic. The study authors stated that, because of the relatively small number of patients included, the claim that both antibiotic treatment modalities are equivalent cannot be made. Moreover, based on the data described above, the timing of usage of both antibiotic modalities might not have been optimal. Additionally, although the data were not statistically analyzed in this way, when the event of antibiotic application (week 15, 8 weeks after completion of initial therapy) is used as the baseline, there seems to be at least a numerical tendency that the systemic antibiotic provided a better clinical adjunctive effect for probing pocket depth, clinical attachment level and bleeding on probing compared with the local antibiotic modality. Similarly, Kaner et al. [41] recently compared the effect of a chlorhexidine chip with systemically administered amoxicillin (1500 mg/day) plus metronidazole (750 mg/day), both applied 1 week after the completion of scaling and root planing. Over the 6-month observation period, the results show that scaling and root planing plus adjunctive chlorhexidine chips provided clinical improvements, but these were not maintained in full over the entire observation period. In the chlorhexidine chip group, probing pocket depth significantly increased again between 3 and 6 months. Scaling and root planing plus systemic amoxicillin/metronidazole was more effective with regard to reduction of pocket depth and gain in clinical attachment. In conclusion, in patients with aggressive periodontitis, the adjunctive effects of local antimicrobials, which have been reported in the literature, do not seem to improve on the adjunctive effect of systemic antibiotics. Only for generalized aggressive periodontitis has an adjunctive clinical effect for tetracycline fibers compared with scaling and root planing alone been shown. How local antimicrobials compare with systemic amoxicillin plus metronidazole with regard to both cost– benefit and effectiveness is currently unknown. Therefore, it seems plausible that the decision to use this type of treatment modality should be made on an individual basis rather than be evidencebased. Surgical treatment of aggressive periodontitis The diagnosis of aggressive periodontitis is often made at an advanced stage of the disease, which means that clinicians will have to treat severely compromised teeth. Consequently, after initial nonsurgical therapy, residual pockets will remain, and these may require surgical treatment. Surgery provides the practitioner with direct access to root surfaces and furcation areas, thus permitting a more thorough debridement. It has also been suggested that because A. actinomycetemcomitans can invade the pocket epithelium, placing itself out of reach of scaling and root planing, the removal of pocket epithelium can help in controlling the disease. Furthermore, intrabony defects can be addressed by either bone-recontouring or regenerative techniques. Although few studies have specifically addressed surgery in aggressive periodontitis, those that have often report positive results. If risk factors, such as smoking, can be controlled, the level of maintenance therapy is high and the patient is compliant, the outcome of periodontal surgery in aggressive periodontitis can be comparable with that in chronic periodontitis. Different surgical techniques are possible in patients with aggressive periodontitis. Access surgery The effectiveness of a modified Widman flap procedure in reducing probing pocket depths is shown in several small-sample-size studies. Christersson et al. [15] treated 25 deep periodontal lesions in seven patients with localized aggressive periodontitis using one of three treatments: scaling and root planing alone; scaling and root planing with additional soft-tissue curettage; or modified Widman flap surgery. Microbiological and clinical effects were monitored up to 16 weeks after treatment. The results showed that scaling and root planing alone did not effectively suppress A. actinomycetemcomitans in periodontal pockets, whereas scaling and root planing combined with soft-tissue curettage and modified Widman flap surgery did. Furthermore, the clinical response to treatment was significantly better for scaling and root planing combined with soft-tissue curettage and for modified Widman flap surgery [16]. Lindhe & Liljenberg [49] treated 16 patients with localized aggressive periodontitis by means of tetracycline administration, scaling and root planing and modified Widman flap surgery, after which the patients were enrolled in a maintenance program for 5 years. Lesions at first molars and incisors in a group of patients with chronic periodontitis were treated in an identical manner and served as controls. The treatment resulted in the resolution of gingival inflammation, gain of clinical attachment and bone refill in angular bony defects. The healing of the lesions in the patients with aggressive periodontitis was similar to the healing observed in patients with chronic periodontitis [49]. In another study, performed by Mandell & Socransky [55], eight patients with localized aggressive periodontitis were treated using modified Widman surgery and a doxycycline regimen. Twelve months after surgery the treatment had been effective in eliminating A. actinomycetemcomitans from the pockets and obtaining mean probing pocket-depth reductions of approximately 3.6 mm, as well as a mean attachment gain of 1.3 mm [55]. Aside from these aforementioned studies there are many case reports in which modified Widman surgery helped to accomplish a stable periodontium [75, 80]. Buchman et al. [10] enrolled 13 patients with aggressive periodontitis in a prospective case series and reported gains in clinical attachment for up to 5 years after initial treatment. Treatment consisted of a combination of scaling and root planing, together with access surgery, without osseous recontouring for pockets deeper than 6 mm. All patients received amoxicillin combined with metronidazole systemically. A significant 2.3-mm gain in clinical attachment was recorded 3 months after therapy. These improvements were maintained for up to 5 years after treatment during which the patients were enrolled in a supportive periodontaltherapy program. In this study, periodontal-disease progression was successfully arrested in 95% of the initially compromised lesions, whilst 2–5% experienced discrete or recurrent episodes of loss of periodontal support [10]. Regenerative surgery An alternative to access surgery to resolve residual periodontal pockets is the use of regenerative techniques in an attempt to resolve intrabony defects. Many different techniques (such as bone grafting, guided tissue regeneration using membranes, the use of biologic modifiers and combinations of the above) have been developed over the years to regenerate vertical bone defects. These techniques were designed for the regeneration of steep vertical defects and have very specific indications, and their effectiveness is dependent on the defect morphology, tooth mobility and furcation involvement. Poor results are expected in the treatment of horizontal bone loss, furcation defects and increased tooth mobility [18]. Bone grafting Bone grafting can lead to regeneration by providing a scaffold for the ingrowth of bone. There are different types of grafts. Autografts are grafts that are harvested from the patient's own body and as such do not cause much tissue reaction during healing. Theoretically, the autograft contains viable bone cells, giving it osteogenic qualities aside from osteoconductive qualities. However, it has been shown that few bone cells survive the harvesting procedure. The autograft is the graft of choice when available, but there are limitations in obtaining it. Alternatives are allografts (e.g. freeze-dried bone allograft), xenografts (bovine or corral derived) and alloplastic materials (e.g. bioactive glass, hydroxyapatite and beta-tricalcium phosphate). Although case reports have been published on their utility in patients with aggressive periodontitis [22, 28, 95], very few controlled studies have been conducted using adequate numbers of patients or in which treatments were compared. Using freezedried bone allografts, Yukna & Sepe [108] reported an average defect fill of 80% in 12 patients with localized aggressive periodontitis at re-entry after 12 months. In addition to this study, using a splitmouth approach, Mabry et al. [52] demonstrated significantly greater bone fill (mean = 2.8 mm) and resolution of osseous defects (mean = 72.7%) in allogeneic freeze-dried bone-grafted osseous bone defects in 16 patients with localized aggressive periodontitis when compared with defects that were treated with debridement only. The best results were obtained when adjunctive systemic tetracycline was administered using the surgical procedure. Evans et al. [27] evaluated a 4:1 (volume by volume) ratio combination of beta-tricalcium phosphate/tetracycline, hydroxyapatite/tetracycline or freeze-dried bone allograft/tetracycline in a split-mouth study of 10 patients with localized aggressive periodontitis. At re-entry, significant decreases in defect depth and pocket depth were detected for each graft material. No significant differences between the different grafting materials were found in terms of hard-tissue or soft-tissue changes. However, a greater percentage of defect fill was demonstrated for hydroxyapatite/tetracycline compared with beta-tricalcium phosphate/tetracycline. The results of these studies show that the use of these grafting materials in combination with tetracycline can result in additional bone fill and resolution of the residual osseous defects in patients with localized aggressive periodontitis. Guided tissue regeneration using membranes Membranes are used to influence the ingrowth of different tissues into intrabony defects. By holding off the ingrowth of epithelium and connective tissue, cells from the periodontal ligament are allowed to grow into the defect, resulting in regeneration of the periodontal attachment. There are nonresorbable and resorbable membranes. Nonresorbable membranes provide a marginally greater attachment gain, but a second procedure is necessary for removing them. Resorbable membranes are biodegradable and do not require a second procedure to remove them; however, they do cause a greater inflammatory response. The use of nonresorbable expanded polytetrafluoroethylene membranes has been shown to be effective for regenerating intrabony defects in aggressive periodontitis in case reports [25, 61, 89, 109]. Using a split-mouth approach, Sirirat et al. [89] compared the effect of a polytetrafluoroethylene membrane with osseous surgery in six patients with aggressive periodontitis. Whilst both treatments were effective 1 year following surgery, probing depth reduction and clinical attachment gain were significantly greater in the polytetrafluoroethylene membrane-treated defects than in the osseous surgery-treated defects, reaching a mean probing pocket-depth reduction of 2.6 mm and a gain in clinical attachment of 2.2 mm. The base of the polytetrafluoroethylene membrane-treated defects showed a significant increase in bone fill. Zucchelli et al. [89] treated similar intrabony defects in 10 patients with localized aggressive periodontits and in 10 patients with chronic periodontitis using titanium-reinforced polytetrafluoroethylene membranes. After 1 year there were no significant differences in the amount of clinical attachment gain, reduction of probing pocket depth or increase in gingival recession between chronic periodontitis and localized aggressive periodontitis groups. DiBattista et al. [25] treated seven patients with intrabony defects on first molars using surgical debridement, polytetrafluoroethylene membrane, polytetrafluoroethylene membrane with root conditioning or polytetrafluoroethylene membrane plus root conditioning and composite graft, consisting of calcium-sulfate, freeze-dried bone allograft and doxycycline. A significant gain in attachment and bone fill was observed for all techniques. There were no significant differences in results between the techniques. The average gain in attachment for all sites combined was 3.2 mm. The number of patients in relation to the number of tested treatments in this study is low and does not permit reasonable conclusions to be made on the effect of the separate techniques. Mengel et al. [61] performed a comparative study on the regeneration of one- to three-wall bony defects in 12 patients with generalized aggressive periodontitis using a bioresorbable membrane or with bioactive glass. They treated 22 defects using a membrane and 20 defects using the alloplastic graft. Both treatment modalities resulted in significant changes in probing pocket depth and in clinical attachment gain of about 4 mm and 3 mm, respectively. No significant differences between the two treatments were found. Biological modifiers The use of enamel matrix proteins (amelogenin) attempts to recreate the physiological environment for the development of the periodontal ligament. This allows the regeneration of new cementum and the formation of new attachment in periodontal defects. The use of enamel matrix protein results in more attachment gain than open-flap debridement in patients with chronic periodontitis [26]. There is, however, little evidence for an advantage in patients with aggressive periodontitis. Most published articles on the use of enamel matrix protein in patients with aggressive periodontitis are case reports [9, 42]. In this regard, Vandana et al. [102] published a case series involving four patients with chronic periodontitis and four patients with aggressive periodontitis. Sixteen intrabony defects were surgically treated with either enamel matrix proteins or surgical debridement alone using a splitmouth design. The mean pocket-depth reduction and amount of defect fill were significant in both treatments, 9 months postsurgery, in both groups of patients. No significant differences in mean pocket-depth reduction, clinical attachment level gain, amount of defect fill or defect resolution were detected between the two treatments, in both groups of patients. This study failed to demonstrate an advantage of using enamel matrix proteins compared with surgical debridement alone. Growth factors and differentiation factors also play an import role in tissue development and healing and are therefore used as tools for gaining attachment. Mediators such as platelet-derived growth factor, insulin-like growth factor, fibroblast growth factor, bone morphogenetic protein and transforming growth factor-beta have shown promising results in animal studies and in vitro [71, 79, 97]. Platelet-rich plasma has been shown to improve clinical and radiographic parameters for compromised teeth [58]. Their disadvantages are the low tissue specificity and unknown systemic effects. At present, their effectiveness in patients with aggressive periodontitis is unknown [23, 80]. There is, however, a case series published by Mauro et al. [58] on the regenerative surgery of intrabony defects with platelet gel. Three patients, who had shown a refractory response to previous treatments, were treated and followed for 15 months. The operated sites showed a reduction of pocket depth and a gain in attachment. Moreover, the effect remained stable during the 15-month follow up, whereas previous treatments had not been as effective [58]. Maintenance therapy Once treatment has resulted in a stable and healthy periodontium, the patient should enter a maintenance program. The purpose of this supportive periodontal therapy is to ensure that periodontal health is maintained after active therapy [40], so that no additional teeth are lost and disease recurrence is prevented. Supportive periodontal therapy should therefore be directed towards risk factors for disease recurrence and tooth loss. Several factors (such as smoking, diabetes mellitus, age, irregular supportive periodontal therapy and ineffective plaque control) have been shown to increase the risk for tooth loss during supportive periodontal therapy in patients with chronic periodontitis [13-15, 48, 59]. A higher risk for disease recurrence and tooth loss after active periodontal therapy can be anticipated in patients with aggressive periodontitis than in patients with chronic periodontitis because of a higher susceptibility for disease progression in patients in the former group. However, the risk factors for tooth loss and/or recurrence of periodontitis in patients with aggressive periodontitis have only recently been investigated. Few studies have assessed the mean tooth loss in patients with aggressive periodontitis during supportive periodontal therapy [8, 35, 85]. The mean annual tooth loss for these patients seems to range from 0.11 [85] to 0.29 [35] teeth, although in the latter study also untreated patients were included. In the recent retrospective study of Baumer et al. [8], tooth loss of 0.13 teeth/year was calculated in patients with aggressive periodontitis. Interestingly, when the authors differentiated between the different types of aggressive periodontitis, patients with generalized aggressive periodontitis exhibited a higher tooth loss, of 0.14 teeth/year, whereas patients with localized aggressive periodontitis only lost 0.02 teeth/year. An additional analysis showed that patients with aggressive periodontitis who followed the supportive periodontal care regularly had a tooth loss of 0.075 teeth/year, whereas patients with irregular periodontal care had a tooth loss of 0.15 teeth/year, stressing the importance of regular periodontal supportive therapy. Age, low educational status and absence of the interleukin-1 composite genotype were significantly correlated with tooth loss and could be defined as risk factors. Nearly significant correlations could be found for smoking, type of aggressive periodontitis, irregular supportive periodontal therapy and the plaque-control record. In terms of risk factors for disease recurrence (defined as the occurrence of probing pocket depths of 5 mm or more at 30% or more of the teeth), Baumer et al. [8] also identified smoking as the main significant risk factor, thereby confirming the data from Kamma & Baehni [40]. In the latter study, the authors also identified stress as a significant predictive factor for future clinical attachment loss. The type of aggressive periodontitis was a nearly significant risk factor for which patients with generalized aggressive periodontitis showed an odds ratio of 35.2 for recurrence and which confirms the results of studies showing long-term stability of the disease in patients with localized aggressive periodontitis [35, 65]. Additionally, an elevated gingival bleeding index and a high plaque-control record showed odds ratios of 31.1 and 63.8, respectively, for disease recurrence. No statistical analysis could be performed for supportive periodontal treatment as a risk factor for disease recurrence because none of the patients receiving regular supportive periodontal therapy experienced recurrence of the disease. However, this stresses the effectiveness of this risk factor. In summary, age, educational status, generalized aggressive periodontitis (vs. localized aggressive periodontitis), absence of the interleukin-1 composite genotype, irregular supportive periodontal therapy, smoking, high mean gingival bleeding index and high plaque-control records are important risk factors for disease recurrence or tooth loss in patients with aggressive periodontitis. Of these, maintenance of supportive periodontal therapy, smoking, high mean gingival bleeding index and high plaque-control records are modifiable risk factors, and the latter two are correlated with the patient's oral hygiene. Therefore, it seems tempting to support the daily oral hygiene of aggressive periodontitis patients with antiseptics as part of the supportive periodontal therapy. To date, only one trial, performed by Guarnelli et al. [32] in 18 patients, has evaluated the effect of an amine fluoride/stannous fluoridecontaining mouthrinse in patients with aggressive periodontitis. In a crossover clinical trial this mouthrinse was effective for reducing the amount of supragingival plaque deposits. However, there was no significant difference compared with the placebo mouthwash on the gingivitis index. The impact of these results on disease progression and tooth loss has not been determined. Regular supportive periodontal therapy has been shown to be effective in controlling the progression of aggressive periodontitis. Maintenance therapy is considered to be a lifelong requirement, but the frequency of recall visits is unclear. The use of many different protocols is being reported in the literature. Deas & Mealey [23] stated that monthly intervals are advisable during the first 6 months of maintenance. Some studies have reported an effective control of disease progression using three to four recall visits per year. To date there are no studies comparing the effect of different follow-up intervals in patients with aggressive periodontitis. In order to define such intervals for patients with chronic periodontitis, the periodontal risk assessment, which estimates the patient's risk profile for the progression of periodontitis, based on six risk factors, was created [47]. Meyer-Baumer et al. [63] recently attempted to confirm the prognostic value of the model in aggressive periodontitis. When the interleukin-1 composite genotype was not taken into account, the impact of this model could be shown to be statistically significant and allowed patients with aggressive periodontitis to be characterized into different risk groups. Finally, needless to say, each visit for supportive periodontal treatment should consist of a thorough medical review, an inquiry into recent periodontal problems, an extensive oral examination, a renewal of oral-hygiene instructions, debridement of residual pockets and prophylaxis. Also, the need to control modifiable risk factors, such as smoking, must be stressed to the patient.