The Legacy Of The Sea Empress

advertisement

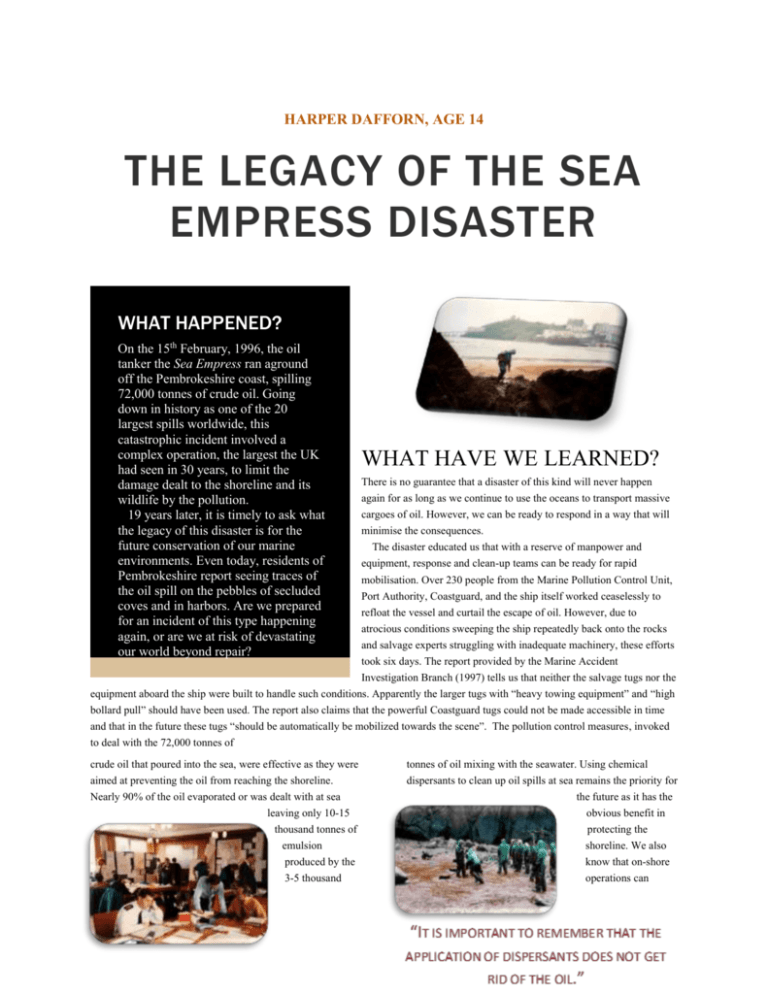

HARPER DAFFORN, AGE 14 THE LEGACY OF THE SEA EMPRESS DISASTER WHAT HAPPENED? On the 15th February, 1996, the oil tanker the Sea Empress ran aground off the Pembrokeshire coast, spilling 72,000 tonnes of crude oil. Going down in history as one of the 20 largest spills worldwide, this catastrophic incident involved a complex operation, the largest the UK had seen in 30 years, to limit the damage dealt to the shoreline and its wildlife by the pollution. 19 years later, it is timely to ask what the legacy of this disaster is for the future conservation of our marine environments. Even today, residents of Pembrokeshire report seeing traces of the oil spill on the pebbles of secluded coves and in harbors. Are we prepared for an incident of this type happening again, or are we at risk of devastating our world beyond repair? WHAT HAVE WE LEARNED? There is no guarantee that a disaster of this kind will never happen again for as long as we continue to use the oceans to transport massive cargoes of oil. However, we can be ready to respond in a way that will minimise the consequences. The disaster educated us that with a reserve of manpower and equipment, response and clean-up teams can be ready for rapid mobilisation. Over 230 people from the Marine Pollution Control Unit, Port Authority, Coastguard, and the ship itself worked ceaselessly to refloat the vessel and curtail the escape of oil. However, due to atrocious conditions sweeping the ship repeatedly back onto the rocks and salvage experts struggling with inadequate machinery, these efforts took six days. The report provided by the Marine Accident Investigation Branch (1997) tells us that neither the salvage tugs nor the equipment aboard the ship were built to handle such conditions. Apparently the larger tugs with “heavy towing equipment” and “high bollard pull” should have been used. The report also claims that the powerful Coastguard tugs could not be made accessible in time and that in the future these tugs “should be automatically be mobilized towards the scene”. The pollution control measures, invoked to deal with the 72,000 tonnes of crude oil that poured into the sea, were effective as they were tonnes of oil mixing with the seawater. Using chemical aimed at preventing the oil from reaching the shoreline. dispersants to clean up oil spills at sea remains the priority for Nearly 90% of the oil evaporated or was dealt with at sea the future as it has the leaving only 10-15 obvious benefit in thousand tonnes of protecting the emulsion shoreline. We also produced by the know that on-shore 3-5 thousand operations can involve long-term and intensive physical work until a degree of control and recovery is achieved. 900 coordinated workers, from major organisations to small groups of amateurs and volunteers, worked round-the-clock for 4 months so that by the time the tourists arrived the main beaches would be clear of conspicuous oil. David Levell, at the time a member of the clean-up team reminds us, however, that appearances can be deceptive – the consequences of the oil spill and the pollution of the environment can persist for many years: “It is important to remember that the application of dispersants does not get rid of the oil. It simply relocates it from the surface of the water into the water column where it is diluted and degraded over time,” he says. He tells us that out of 100 different studies carried out after the incident, “One of the longest lasting effects was found in the invertebrate animal communities that live in the soft sediments within the waterway. Some of the populations of amphipods (small shrimp-like animals) took more than 5 years to recover to their pre-spillage densities.” Amongst the other casualties were the Scoters (a sea duck), which were caught by the oil spill during their seasonal migration. In fact, the numbers of bird victims exceeding 7,000 which were admitted into make-shift hospitals were but a portion of the numbers hit. Shockingly, even those which were freed post-treatment had, on average, just nine days left to live. Another important aspect of learning from the disaster is the behind-the-scenes readiness. The report of the Pollution Control Unit (1996) tells us “The basic requirements were all in place in advance of the spill: a logistics structure, trained teams specializing in at sea recovery, spray monitoring, and shoreline clean-up techniques; stockpiles of equipment and dispersants; and surveillance and dispersant spray aircraft.” Yet readiness must be a top-to-bottom prearrangement. By Harper Dafforn age 14 MrLevell reminds us that “Oil Spill Contingency Plans are living documents and need to be exercised, reviewed and updated continuously – they are useless if left on the bookshelf gathering dust.” He refers to his own experience of training and preparation prior to the Sea Empress, namely that he had participated in a training exercise around a hypothetical scenario just a few weeks beforehand, and this made the response “so much more effective by already knowing and working with the key players in the environmental team”. The equation for a disaster of this sort consists of complex combinations of human error and adverse conditions. Most of us can rest assured that the analysis following the event is meticulously detailed and is less about assigning blame and more about learning from the experience. If a tragedy like this should happen again tomorrow, I, for one, am comforted that everyone will be capable of working together and drawing from previous experience of hard lessons learned. With special thanks to David Levell.(Environmental Manager, Milford Haven Port Authority)