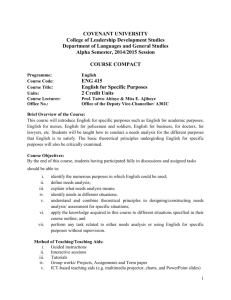

2015-16 Module Brochure

advertisement

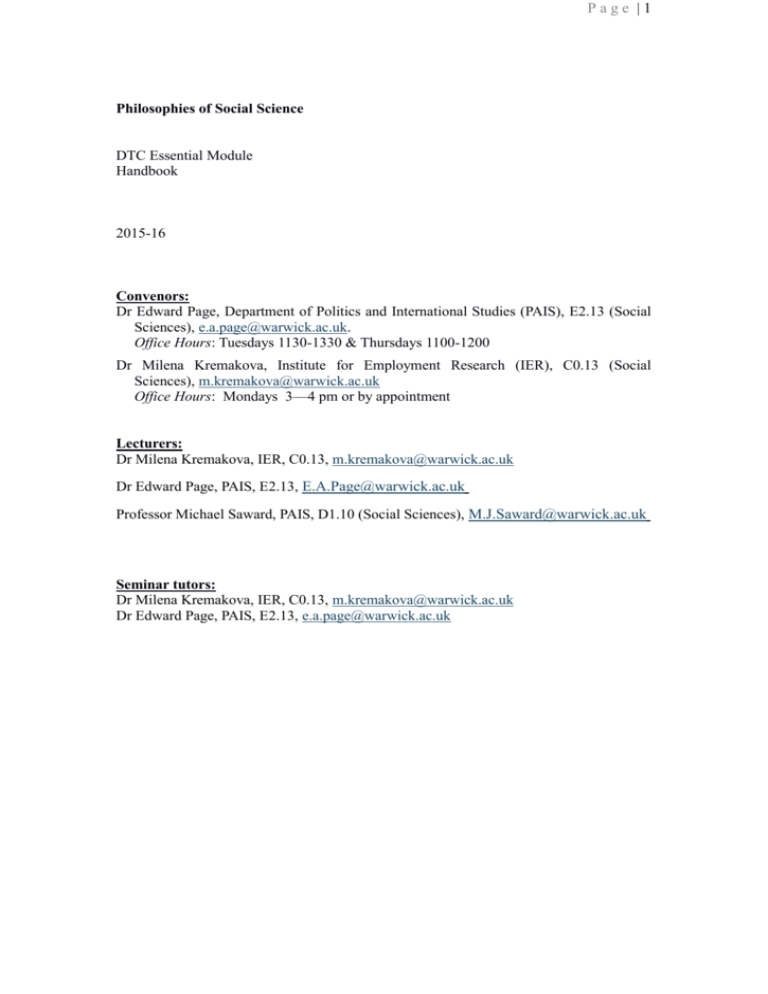

Page |1 Philosophies of Social Science DTC Essential Module Handbook 2015-16 Convenors: Dr Edward Page, Department of Politics and International Studies (PAIS), E2.13 (Social Sciences), e.a.page@warwick.ac.uk. Office Hours: Tuesdays 1130-1330 & Thursdays 1100-1200 Dr Milena Kremakova, Institute for Employment Research (IER), C0.13 (Social Sciences), m.kremakova@warwick.ac.uk Office Hours: Mondays 3—4 pm or by appointment Lecturers: Dr Milena Kremakova, IER, C0.13, m.kremakova@warwick.ac.uk Dr Edward Page, PAIS, E2.13, E.A.Page@warwick.ac.uk Professor Michael Saward, PAIS, D1.10 (Social Sciences), M.J.Saward@warwick.ac.uk Seminar tutors: Dr Milena Kremakova, IER, C0.13, m.kremakova@warwick.ac.uk Dr Edward Page, PAIS, E2.13, e.a.page@warwick.ac.uk Page |2 Introduction This module introduces students to some of the standard methodological and theoretical problems posed by social inquiry. Many of the issues to be discussed relate to one key question: are the methods of the social sciences essentially the same or essentially different from those of the natural sciences? The topics to be addressed include: introduction to social research; questions in the philosophy of knowledge relating to science, realism, language and materials; objectivity in the social sciences; challenges to objectivity via standpoint epistemology; and the feminist and postmodern/postcolonial challenges to objectivity. Although the issues will be illustrated in specific texts, you are also encouraged to pursue parallel arguments in different sources from your own disciplines and across disciplines. The reading list is designed to encourage the consultation of diverse sources in order to identify common concerns and problems. There is 'Essential reading' for each session in order to provide a focus to discussion which all students are required to read in advance of each seminar. The ‘Further reading’ offers an opportunity to locate the topic in a wider context or to pursue more specialised aspects for essays. Schedule The lectures for Philosophies of Social Science will take place in the Humanities building on Tuesdays, 2—3pm, in room H0.60. Seminars will take place at 3-4 and 4-5pm in H0.60 (led by Ed Page and Milena Kremakova). Topics Lecturer Week 1 (Tues 6 Oct) Induction week: No lecture or Induction week: No seminar lecture or seminar Week 2 (Tues 13 Oct) Introduction: making sense of the Milena Kremakova social world and Ed Page Week 3 (Tues 20 Oct) Explanations in Social Science Week 4 (Tues 27 Oct) Rational choice theory, collective action, and game theoryEd Page Ed Page Week 5 (Tues 3 Nov)Interpretation and understanding in social scienceMilena Kremakova Week 6 (Tues 10 Nov) Reading Week / Presentation Week Ed Page and Mike Saward Week 7 (Tues 17 Nov) Elements of constructivism performative Week 8 (Tues 24 Nov) Social theory from the margins: Milena Kremakova Social science in crisis? Week 9 (Tues 3 Dec) Making sense of bad science, weird Ed Page science and denial: why do (smart) Interpretation: Michael Saward and the Page |3 people believe weird things? Week 10 (Tues 10 Dec) Making sense of suicide terror Ed Page and Milena Kremakova Page |4 Background Readings Benton, T. and Craib, I. (2001) Philosophy of Social Science (Basingstoke: Palgrave). Hollis, M. (1994) The Philosophy of Social Science (Colorado: Westview). Delanty, G. and Strydom, P. (2003) (eds) Philosophies of Social Science: The Classic and Contemporary Readings (Maidenhead: Open University Press). Chalmers, A. F. (2000) What is this Thing Called Science? An Assessment of the Nature and Status of Science and its Methods. Milton Keynes: Open University Press (available in several editions with supplementary chapters. Any edition is worth purchasing and reading as a whole). Outhwaite, William (1987) New Philosophies of Social Science: Realism, Hermeneutics and Critical Theory, London: Macmillan. These very useful and wide-ranging books are available from the bookshop or Amazon for around £15 and multiple copies are in the library. Benton and Craib is more accessible and fairly sociological, whereas Hollis’s book has a more philosophical orientation. Whilst both of these are textbooks, Delanty and Styrdom is essentially an anthology of short excerpts from classic texts in the philosophy of social science, but with the addition of a very useful introduction and linking discussions. Outhwaite is an excellent introduction to alternative approaches to the understanding of social science. Other useful texts include the following (starred items are particularly useful): *Chalmers, A. F. (2000) What is this Thing Called Science? An Assessment of the Nature and Status of Science and its Methods. Milton Keynes: Open University Press (available in several editions with supplementary chapters. Any edition is worth purchasing and reading as a whole). *Elster, J. (1989) Nuts and Bolts for the Social Sciences (Cambridge: CUP). Elster, J. (1989) The Cement of Society (New York: Cambridge University Press). *Elster, J. (2007) Explaining Social Behaviour: More Nuts and Bolts for the Social Sciences (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).Fay, B. (1996) Contemporary Philosophy of Social Science (Oxford: Blackwell). Hay, C. (2002) Political Analysis (Basingstoke: Palgrave). *Hollis, M. and Smith, S. (1990) Explaining and Understanding International Relations (Oxford: Clarendon) Hollis, M. (1996) Reason in Action: Essays in the Philosophy of Social Science (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press). Kellstedt, P.A. and Whitten, G.D. (2008) The Fundamentals of Political Science Research (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press). *Little, D. (1991) Varieties of Social Explanation: an introduction to the philosophy of social science (Boulder: Westview). *Flyvbjerg, B. (2001) Making Social Science Matter: Why social inquiry fails and how it can succeed again (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press). *Moses, J.W. and Knutsen, T.L. (2010) Ways of Knowing: Competing Methodologies in Social Science (Basingstoke: Palgrave). Popper, K. (1991) The Poverty of Historicism (London: Routledge). Pratt, V. (1978) The Philosophy of the Social Sciences (London: Methuen).Root, M. (1993) Philosophy of Social Science (Oxford: Blackwell). *Rosenberg, A. (1995) Philosophy of Social Science (Boulder: Westview). Page |5 Week 2: Introduction: Making sense of the social world (Milena Kremakova and Ed Page) “What are we doing when we attempt to study human social life in a systematic way?” (Benton and Craib 2001). “If even in science there is no a way of judging a theory [but] by assessing the number, faith and vocal energy of its supporters, then this must be even more so in the social sciences: truth lies in power” (Lakatos 1978). The very idea of a ‘social’ science implies two things. First, that it is somehow distinct from ‘natural’ science; second, that it is some sort of ‘science’. This leads to further questions. What is science? What is distinctive about social reality? Why is there such disagreement across the social sciences about how to study social reality? What can we know about social reality? In this introductory session, we discuss some of the contrasting approaches to studying the social world and chart the main debates across the social sciences based on assumptions of the nature of social reality (ontology) and what we can know about it (epistemology). Seminar Questions: 1. How, if at all, is ‘social research’ different from other ways we can make sense of the social world? 2. In attempting to make sense of social phenomena, to what extent should we distinguish between explanations, understandings and interpretations? 3. What is ‘positivism’ - and what are its limitations? Is all science necessarily ‘positivist’? 4. What is the difference between deduction, induction, and retroduction? Is one of these superior to the other two? 5. What should the focus of the social sciences be the behaviour of large social groups and associated institutions (holism) or the behaviour and characteristics of individual human agents (atomism)? Essential Reading: Hollis, M. (1994) The Philosophy of Social Science (Colorado: Westview), Ch.1,Ch.2,Ch.3. Chalmers, A.F. (1982) ‘The Theory-Dependence of Observation’. Chapter 3 of What is this Thing Called Science? (2nd edition) Milton Keynes: Open University Press. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry, ‘Theory and Observation in Science’: http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/science-theory-observation/ Further Reading: Adorno, T. W. et al 1976. The Positivist Dispute in German Sociology (Heineman) Benton, T & Craib, I. 2001. Philosophy of Social Science Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, Ch.1. Elster, J. (2007) Explaining Social Behaviour: More Nuts and Bolts for the Social Sciences (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), Ch.1,3. Hammersley, M. (1995). The Politics of Social Research. London: Sage. Page |6 Hay, C. (2002) Political Analysis (Basingstoke: Palgrave), Ch.2. Hemple, C. (1965) Aspects of Scientific Explanation (New York: Free Press), essay 12. Kemp, Steve 2007. ‘Concepts, Anomalies and Reality: A Response to Bloor and Feher,’ Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 38 (1): 241-253 Kuhn, T.S. 1962. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (U of Chicago Press) Lakatos, I. 1978. 'Falsification and the methodology of scientific research programmes' in Collected Papers, Volume I (Cambridge UP) Laudan, L. 1996. ‘“The Sins of the Fathers...”: Positivist Origins of Postpositivist Relativisms,’ Beyond Positivism and Relativism (Westview Press) Laudan, L. 1989. ‘If It Ain't Broke, Don't Fix It,’ The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science 40 (3): 369-375 Popper, Karl 1963. Conjectures and Refutations (Routledge and Kegan Paul) Chs 3, 10. Rosenberg, A. (1998) Philosophy of Social Science. 2nd Edition. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, Ch.1 (pp.1-27). Winch, P. 1976. The Idea of a Social Science (Routledge and Kegan Paul). Page |7 Week 3: Explanations in Social Science I (Ed Page and Milena Kremakova) ‘In the long run it is the theory that is supported by the successful explanations it generates, not the other way around (Elster 2007: 20). ‘To explain a social fact it is not enough to show the cause on which it depends; we must also, at least in most cases, show its function in the establishment of social order’ (Durkheim 1950: 97). In this week, we take a closer look at some prominent theories of social science explanation. Explanatory approaches make sense of social facts, events, and states-ofaffairs in terms of how they result from other social facts, events, and states-of-affairs. Such theories can be separated into those that work at the level of the group or society (holist accounts) and those that work at the level of the individual agent or organism (artomist accounts). After exploring the concept of explanation, we explore holist accounts of explanation - such as functionalism and structuralism - make sense of a wide range of social phenomena including social conflict and social cooperation. Seminar questions: 1. What is the basic structure of an explanation? 2. What grounds may be used to support an explanation 3. Are all holist explanations causal explanations? 4. What are the core assumptions of functionalist and structuralist explanations of social phenomena? Are they defensible? Essential Reading: Elster, J. (2007) Explaining Social Behaviour: More Nuts and Bolts of the Social Sciences (Cambridge: CUP), Ch.1 (pp.9-31). Little, Ch.5, ‘Functional and Structural Explanation’, pp.90-113. Hollis, M. (1994) 'Systems and Functions', in The Philosophy of Social Science (Cambridge: CUP), 94-114. Further reading: Dore, R.P. (1973) ‘Function and Cause’, in A. Ryan (ed) The Philosophy of Social Explanation (Oxford: OUP), pp.65-81. Durkheim, (1950[1895]) The Rules of Sociological Method. Translated by S. A. Solovay and J. H. Mueller. New York: The Free Press. Gould, S.J. and Lewontin, R.C. (1979) ‘The spandrels of San Marco and the panglossian paradigm: a critique of the adaptationist programme’, Proceedings of the Royal Society of London 205 (1161): 581-598. Kellstadt and Whitten (2008), ‘Evaluating causal relationships’, in The Fundamentals of Political Science Research (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), pp.45-66. Page |8 Marx, K. (1977) Preface to The Critique of Political Economy, in D. McLellan (ed) Karl Marx’s Selected Writings (Oxford: OUP), pp.388-90, available electronically here https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1859/critique-pol-economy/preface.htm Radcliffe-Brown, A.R. (1952) Structure and Function in Primitive Society (New York: Free Press), pp.133-211. Root (1993) Ch.4, ‘Functional theories in sociology and biology’, 78-99. Rosenberg (1995) Ch. 5, ‘Functionalism and Macrosocial science’, pp.124-152. Page |9 Week 4: Explanations in Social Science II: rational choice, collective action and game theory (Ed Page) ‘A rational agent’s gotta do what a rational agent’s gotta do!’ (Hollis 1996:60). This week, we take a closer look at a prominent set of ‘atomistic’ theories of social science explanation. Such approaches make sense of social facts, events, and states-ofaffairs in terms of how they result from the aggregated effects of individual agents. After further exploring the concept of explanation in terms of different forms of inference, we explore atomist accounts of explanation - such as rational choice, collective action and game theory - make sense of a wide range of social phenomena including social conflict, social cooperation, and environmental degradation. Seminar questions: 1. Sometimes people fail to satisfy the conditions of ‘rational action’. Is this a problem for the theory or a problem for the people? 2. What is a ‘tragedy of the commons’? To what extent can such tragedies be avoided? 3. What are the implications of game theory for our understanding of global climate change and other environmental problems? Essential Reading: Hollis, M. (1994) 'Games with rational agents', The Philosophy of Social Science (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), pp.115-41. Little, D. (1991) 'Rational Choice Theory', Varieties of Social Explanation (Colorado: Westview), pp.39-67. Hardin, G. (1968) ‘The Tragedy of the Commons’, Science, 162, 3859, pp.1243-48. Further reading: Axelrod, R. (1997) The Complexity of Cooperation: agent-based models of competition and collaboration (Princeton: Princeton University Press), pp. 3-29. Benton and Craib, Ch. 4. Binmore, K. (2007) Game Theory: A very Short Introduction (Oxford: OUP). Brams, S. (2000) ‘Game theory: pitfalls and opportunities in applying it to international relations’, International Studies Perspectives, 1(3), pp.221-232. Dawkins, R. (1989) The Selfish Gene (2nd edition) (Oxford: OUP). Elster J. (1990) ‘When Rationality Fails’ in Karen S. Cook and M. Levi, The Limits of Rationality (Chicago: Chicago University Press), pp. 19-59. Gardiner, S. (2001) The Real Tragedy of the Commons, Philosophy and Public Affairs, 30(4), pp.387-41. Hardin, G. (1998) ‘Extensions of "The Tragedy of the Commons’, Science 280(5364): 682-83, 1 May. P a g e | 10 Hargreaves, S. Hollis, M., Lyons, B., Sugden, R. Weale, A. (1992) The Theory of Choice: A Critical Guide (Oxford: Blackwell), Ch. 1, 3. Hargreaves, S.P. and Varoufakis, Y (1995) Game Theory: A Critical Introduction (electronic) (London: Routledge), pp.1-40. Hindmoor, A. (2006) Rational Choice (New York: Palgrave). Hollis and Smith, ‘The Games Nations Play (2)’, Explaining and Understanding International Relations, pp.171-95. Hollis, M. (1996) ‘The Ant and the Grasshopper’ and ‘A rational agent’s gotta do what a rational agent’s gotta do!’, in Reason in Action (Cambridge: CUP), pp.60-1; 80-87. Hollis, Reason in Action, Ch.2, 3 and 5. Kahneman, D. and Tversky, A. Judgement under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), pp. 3-20. Little, Ch.3, ‘Rational Choice Theory’, pp. 39-67. Olson, C. (1965) The Logic of Collective Action (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press). Osbourne, M.J. (2004) An Introduction to Game Theory (New York: OUP). Oström, E. (1992) ‘Covenants with and without the sword: Self-governance is possible’, The American Political Science Review, 86(2), pp.404-17. Oström, E., Burger, J., Field, C.B., Norgaard, R.B., and Policansky, ‘Revisiting the commons: local lessons, global challenges’, Science, 284, 9 April 1999, pp.278-82. Root (1993) Ch5, ‘Rational choice theories in positive and normative economics’, pp.100-23. Rosenberg (1995) Ch. 6, ‘Individualism’s Invisible Hands’, pp. 153-87. Schelling, T. (1960) The Strategy of Conflict (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press), Ch.1 (pp.3-20) and Ch. 10 (pp.230-54). Sen, A. (1982) ‘Rational Fools: A Critique of the Behavioural Foundations of Economic Theory’ in his Choice, Welfare and Measurement (Oxford: Blackwell). Stone, R.W. (2001) ‘The use and abuse of game theory in international relations’, Journal of Conflict Resolution 45(2), pp.216-44. Ward, H. (2005) ‘Rational Choice’ in D.Marsh and G.Stoker (eds) Theory and Methods in Political Science (Basingstoke: Macmillan), Ch.3. P a g e | 11 Week 5 Interpretation and understanding in social science (Milena Kremakova) ‘Is the meaning of others’ behaviour what they mean by it? (Fay 1996: 136) In this session, we discuss alternatives to positivist social science: interpretative approaches which distinguish it from natural science, and critical realism which seeks the middle ground between rationalism and interpretativism. Interpre(ta)tive sociologies have their origins in the neo-Kantian critique of sociological positivism and economic deretminism in the social sciences. The umbrella term ‘interpretivism’ (German: verstehende Soziologie, from ‘verstehen’: understand, comprehend) includes a range of very different approaches which are unified by the argument that, unlike natural science which studies a domain of objects lacking intrinsic meaning, the meanings and understandings of actors play a central part for social science. Interpretative social scientists see social science as intertwined with the reality which it studies. They see the social and cultural world as a milieu of meaning, are especially interested in those elements of reality which are conflicting or contested by different societal agents. Examples of authors in the interpretative tradition include Max Weber, Georg Simmel, Alfred Schütz, Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann, Peter Winch, Howard Becker, Claude Levi-Strauss and others. In turn, Realism, notably a strand of it known as Critical Realism, seeks a middle ground between positivism and interpretivism. Critical Realism seeks to provide a theoretical underpinning for social science that has stressed its affinities with the natural sciences without losing the grasp on interpretation of meanings. Critical realists acknowledge that the existence of human agency and the limited possibilities for experiment in social science make it difficult to locate and identify these structures. In this session, we discuss realist arguments, on the example to a debate between Andrew Sayer and John Holmwood about the relationship between capitalist and bureaucratic structures, on the one hand, and gender structures, on the other. Seminar questions 1. Are there aspects of social life which are not socially constructed? What are they? 2. Is it possible to incorporate a concern with actors’ meanings while still allowing that there are causes operating in the social world? 3. Can social action be explained as rule following? 4. Is ‘Verstehen’ a form of ‘empathetic’ understanding, or something else? 4. Are realists correct that experiments cannot be a key tool for social science? Are there alternatives to experiment that social science can employ? 5. How persuasive is Holmwood’s critique of Sayer? Essential Reading: [good all-round summary] Benton, T & Craib, I. 2001. Philosophy of Social Science. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, Ch.5. P a g e | 12 [Interpretivism] Berger, P. and T Luckmann, 1966. The Social Construction of Reality (Anchor), ch. 1 (a PDF of the whole book is available online here: http://perflensburg.se/Berger%20social-construction-of-reality.pdf) [Critical Realism] Sayer, Andrew 2000. ‘System, Lifeworld and Gender: Associational versus Counterfactual Thinking,’ Sociology 34 (4): 705-725. Further Reading: Good general treatments of 'hermeneutics' or 'interpretative' social inquiry are: Benton and Craib, ‘Rationality as rule-following’, Chapter 6, pp.93-106.Berger, P. L. (1963) Invitation To Sociology: A Humanistic Perspective. (chapter 1 is available online here http://www.sociosite.net/topics/texts/berger.pdf) Outhwaite, W. 1975. Understanding Social Life: the Method Called Verstehen (Allen and Unwin) Chs 2, 5, 6 David, M. (2010) Methods of Interpretive Sociology (SAGE Benchmarks in Social Research Methods), SAGE (ch.1 which has a historical timeline of interpretative approaches is available online here http://uk.sagepub.com/sites/default/files/upmbinaries/35377_Davidvolume_1.pdf Delanty, G. and Strydom, P. (2003) (eds) Philosophies of Social Science: The Classic and Contemporary Readings, texts from Dilthey, Simmel, Winch, Gadamer and Ricoeur (pp.99-181). Fay, B. (1996) Ch.7, ‘Is the meaning of others’ behaviour what they mean by it? Contemporary Philosophy of Social Science (Oxford: Blackwell). Gadamer, H-G 1986. ‘The Historicity of Understanding’ in K. Mueller-Vollmer (ed) The Hermeneutics Reader. Oxford: Blackwell. Hay, C. (2002) Political Analysis (Basingstoke: Palgrave), pp.216-250. Hollis, ‘Understanding Social Action’ (pp.142-162) and ‘Self and Roles’ (163-182). MacIntyre, A. ‘The idea of a social science’, in A. Ryan (ed) The Philosophy of Social Explanation, pp.15-32. Mottier, Veronique. 2005. The interpretive turn: history, memory and storage in qualitative research. Forum: Qualitative social research, vol.6, No.2, May 2005. Available online here: http://www.qualitativeresearch.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/456/972. Rosenberg, Ch. 4, ‘Interpretation’, pp.90-123. Warnke, G. 1987. Gadamer: Hermeneutics, Tradition and Reason. Oxford: Polity Weber, M. 1922. ‘Science as a Vocation’. (Wissenschaft als Beruf, ‘ from Gesammlte Aufsaetze zur Wissenschaftslehre’ (Tubingen, 1922), pp. 524‐55. Originally delivered as a speech at Munich University, 1918. English translation available online here: http://www.wisdom.weizmann.ac.il/~oded/X/WeberScienceVocation.pdf Weber, Max The Nature of Social Action in Runciman, W.G. 'Weber: Selections in Translation' Cambridge University Press, 1991. p7.Winch, P. (1990 [1958]) The Idea of a Social Science and its relation to philosophy, (electronic) (2nd edition) (London: P a g e | 13 Routledge), Ch.1, pp.1-39 (see also Winch, P. 1974. ‘The idea of a social science’ in B.R. Wilson (ed) Rationality, Oxford: Blackwell). In the conservatism of interpretation, and a critique of that position, see: Habermas, J. 1970. 'On systematically distorted communication' Inquiry 13 (3) Gadamer, H-G 1976. 'On the scope and function of reflection' in Philosophical Hermeneutics (U of California Press) Gadamer, H-G 1986. 'Rhetoric, hermeneutics and the critique of ideology' in K. MuellerVollmer (ed) The Hermeneutics Reader (Blackwell) Outhwaite, W. 1987. New Philosophies of Social Science: Realism, Hermeneutics and Critical Theory (Macmillan) Chs 4, 5 On Critical Realism, see: Archer, M. 1996. ‘Social integration and system integration: developing the distinction,’ Sociology 30 (4): 679-699. Collier, A. 1994. ‘Experiment and Depth Realism’ in Critical realism: An Introduction to Roy Bhaskar’s Philosophy (Verso) [Critical Realism] Holmwood, John 2001. ‘Gender and Critical Realism: A Critique of Sayer,’ Sociology 35 (4): 947-965. For criticisms of ‘Critical Realism’ in social science see: Kemp, S. 2005. ‘Critical Realism and the Limits of Philosophy,’ European Journal of Social Theory 8 (2): 171-191 King, A. 1999. ‘The Impossibility of Naturalism: The Antinomies of Bhaskar’s Realism,’ Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 29 (3). ‘Critical realism’ has had considerable impact in economics and management. See: Fleetwood, S. and S Ackroyd 2004. Critical Realist Applications in Organisation and Management Studies (Routledge) Lawson, T. 1997. Economics and Reality (Routledge) Reed, M. 2005. 'Reflections on the ‘Realist Turn’ in Organization and Management Studies', Journal of Management Studies, 42 (8): 1621-1644. P a g e | 14 Week 6:Reading Week / Presentation Week In this week, students will be encouraged to give presentations in groups that explore the ontological, epistemological, and methodological debates raised in the module so far for the conduct of research in their disciplines and sub-disciplines. Groups will be assigned in the first two weeks of the module and presentations that bring together a range of disciplinary accounts of a common methodology or theoretical framework (such as discourse analysis, game theory, or critical theory) are also encouraged. The session will run 2-3pm in H0.60 and will be for all students (the 3pm and 4pm seminars will be replaced by this session). P a g e | 15 Week 7: Elements of Interpretation: constructivism and the performative (Michael Saward) “Do our writings and our utterances reflect or describe the world, or do they intervene in it? Do they, perhaps, help to make it? (Loxley 2007). “To say that ‘representation means this’, pointing to a specific instance or practice, is not the most interesting or important point to make about representation. It is less about pinning down meaning, more about asking how meanings are generated and contested; or … how something absent is rendered as present” (Saward 2010). A number of approaches in the philosophy of social sciences have stressed the importance of interpreting meanings from social or cultural contexts, including phenomenology, ethnomethodology, constructivism and performativity. In this session, we will focus in particular on the latter two, though many core elements of them derive from the former two. The concept of representation – a critical notion in politics, culture, and other domains – will be used as a case study, specifically Saward’s departure from (a) representation as a social and political feature with a context-independent meaning and reference to (b) a view of representation as a performatively produced social construction. Seminar Questions: 1. What does it mean to say that a social phenomenon might be ‘socially constructed’? 2. What conceptions of language, discourse, and culture are at play in constructivist thinking? 3. How can social phenomena, such as gender in the work of Butler, be understood as performatively produced? 4. What are the main strengths and weaknesses of constructivist and performative approaches? Essential Reading: Hacking, I. 2000. The Social Construction of What? (Harvard University Press), ch.1 Lynch, M. 1998. ‘Towards a Constructivist Genealogy of Social Constructivism’, in I. Velody and R. Williams (eds), The Politics of Constructionism (Sage) Loxley, J. 2007. Performativity (Routledge),esp. ch.6. Saward, M. 2010. The Representative Claim (Oxford University Press), chs. 1 & 2. Further Reading: Austin, J.L. 1975. How To Do Things With Words (2nd edn) (Clarendon Press) Brassett, J. and C. Clarke. 2012. ‘Performing the Sub-Prime Crisis: Trauma and the Financial Event’. Political Sociology 6 (1): 4-20. Butler, J. 1990. ‘Performative Acts and Gender Constitution’, in S. Case (ed) Performing Feminisms: Feminist Critical Theory and Theatre (Johns Hopkins University Press). Butler, J. 1999. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (Routledge) Butler, J. 2010. ‘Performative Agency’, in Journal of Cultural Economy 3 (2): 147-161. Callon, M. 2010. ‘Performativity, Misfires and Politics’, in Journal of Cultural Economy 3 (2): 163-169. Collins, R. 1994. ‘The Microinteractionist Tradition’, in Four Sociological Traditions (Oxford University Press), final chapter. Schaap, A., S. Thompson, L. Disch, D. Castiglione and M. Saward. 2012. ‘Critical Exchange on Michael Saward’s The Representative Claim’, in Contemporary Political Theory 11: 109–127. Rosenberg, A. 2012. Philosophy of Social Science (4th edition) (Westview Press), ch.7. P a g e | 16 Week 8: Social theory from the margins: Social science in crisis? (Milena Kremakova) This session will examine three main alternative politics of knowledge production which challenge the status quo: Marxist, feminist and postcolonial. Marx identified the proletariat as a ‘universal class’ that carried with it the principle for transformation of capitalist modernity and the realisation of a more just, communist society. The ‘standpoint of the proletariat’ was argued to be the basis of social criticism and social transformation. Later on, feminist scholars developed this idea into a ‘feminist standpoint’ position. Postcolonial theory situated the subject in the margins of history from where the subaltern subject tried to speak but was often not heard. We shall discuss how dominant discourses of legitimate knowledge by marginalising ‘other’ sources of knowledge. This lecture will look at this model of social criticism and assess the implications of these marginalised theories for ideas of objectivity. It will also explore the claim that the social sciences are facing an empirical crisis, and if so what might be done in response. Seminar Questions: 1. How do marginalised figures (the proletariat, the woman, the subaltern) become the point of view from which criticism can be made? Is it fruitful to rethink academic disciplines from these alternative standpoints? 2. Can social research be independent of political values and influences? Can the Marxist, feminist or postcolonial critic avoid replicating that which is being criticised as imperial or colonial in the first place? 3. Why do Savage and Burrows say that contemporary social science is in crisis? Can any of the above strands of social science respond to this crisis? 4. Is it true that many of methodological tasks once performed by the social sciences are now performed better by commercial agencies situated outside of the academy? Essential Reading: [Marxism] Lukacs, Georg 1968. ‘The Standpoint of the Proletariat’ in History and Class Consciousness: Studies in Marxist Dialectics. London: Merlin Press. [feminism] Harding, Sandra 1991. ‘”Strong objectivity” and socially situated knowledge’ in Whose Science? Whose Knowledge: Thinking from Women’s Lives, Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [postcolonialism] Spivak, Gayatri C. 1998. ‘Can the Subaltern Speak?’ in Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg (eds.) Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture (University of Illinois Press). [social science in crisis?] Savage, Mike and Burrows, Roger 2009. ‘Some Further Reflections on the Coming Crisis of Empirical Sociology’. Sociology, 43, 4, pp.762772. Further Reading: On Marxism Althusser, Louis 1969. ‘Contradiction and Over-Determination’ in For Marx translated by Ben Brewster. London: Penguin Press. Althusser, Louis 1970. ‘From Capital to Marx’s philosophy’ in L. Althusser, E. Balibar Reading Capital (New Left Books) Hammersley, M. 2000. Taking Sides in Social Research: Essays on Partisanship and Bias (Routledge) Ch 1 P a g e | 17 Holmwood, John and Alexander Stewart 1983. ‘The Role of Contradictions in Modern Theories of Social Stratification’, Sociology 17 (2): 234-54. Marx, Karl 1987 [1845]. The German Ideology: Introduction to a Critique of Political Economy. London: Lawrence & Wishart Ltd. Pels, D. 1998. ‘The Proletarian as Stranger’ History of the Human Sci 11 (1): 49-72. On Feminism: Grosz, E. 1986. ‘What is feminist theory?’ in C, Pateman, E Gross (eds) Feminist Challenges (Allen and Unwin). Hawkesworth, M. 1989. ‘Knower, knowing, known: feminist theory and claims of truth’ Signs 14 (3). Harding, S. 2004. The Feminist Standpoint Theory Reader: Intellectual and Political Controversies. London: Routledge. Hartsock, N. 1988. ‘The feminist standpoint: developing the ground for a specifically feminist historical materialism’ in S. Harding (ed) Feminism and Methodology OUP Spivak, G. C. 1996. ‘Subaltern Studies Deconstructing Historiography’ in D. Landry & G. MacLean (eds) The Spivak Reader: Selected Works of Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak (Routledge). Stanley, L. and S. Wise 1993 Breaking Out Again: Feminist Ontology and Epistemology (Routledge). On Postcolonialism: Harding, S. Whose Science? Whose Knowledge? Ch 5 Du Bois, WEB 1903. The Souls of Black Folk. Various imprints Lemert, C. 1994. 'Dark thoughts about the self' in C. Calhoun (ed) Social Theory and the Politics of Identity (Blackwell) Collins, Patricia Hill 1990. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. Boston: Unwin Hyman. Holmwood, John 1995. ‘Feminism and Epistemology: What Kind of Successor Science?’, Sociology 29(3): 411-428. Phillips, A. 1992. 'Universal pretensions in political thought' in M. Barrett, A. Philips (eds) Destabilising Theory: Contemporary Feminist Debates (Polity) Mohanty, Chandra T. 1988. ‘Under Western Eyes: Feminist Scholarship and Colonial Discourses’ Feminist Review Autumn 30: 61-88 On the debate about the crisis in sociology Holmwood, John 2010. ‘Sociology’s Misfortune: Disciplinarity, Interdisciplinarity and the Impact of Audit Culture’. The British Journal of Sociology. 61, 4, pp.639-658. Holmwood, John and Scott, Scott 2007. ‘Editorial Foreword: Sociology and its Public Face(s)’. Sociology, 41, 5, pp.779-783. Crompton, Rosemary 2008. ’Forty Years of Sociology’. Sociology, 42, 6, pp.1218-27. Webber, Richard 2009. ‘Response to “The Coming Crisis of Empirical Sociology”: An Outline of the Research Potential of Administrative and Transactional Data’. Sociology, 43, 1, pp.169–78. Gane, Nicholas 2011. ‘Measure, Value and the Current Crises of Sociology’, Sociological Review, 58, s2, December, pp.151-73. Burrows, Roger and Gane, Nicholas 2006. ‘Geodemographics, Software and Class’, Sociology, 40, 5, pp.793-812. Thrift, Nigel 2005. Knowing Capitalism. London: Sage. P a g e | 18 Week 9: Weird science, bad science, and denial (Ed Page) ‘Smart people believe weird things because they are skilled at defending beliefs they arrived at for non-smart reasons’ (Shermer 2007: 283). Here we explore the limits of science and the phenomenon of denial. ‘Conspiracies of silence’, ‘political spin’, ‘being economical with the truth’, ‘turning a blind eye’, ‘seeing what you want to see’, ‘selective memory’: scholars across the social sciences have been exercised by how and why individuals, firms, and governments frequently assert that something didn’t happen, does not exist, or is not true despite being aware that these things happened, did exist, and are known about (Cohen 2001). Is the explanation for such denial a matter of psychology, pathology, culture, or political science? Seminar Questions 1. What is the difference between contesting a social fact, interpretation, or implication? 2. What are the arguments of those who deny evolution or the Holocaust? To what extent do they presuppose the rejection of ‘sound-science’? 3. Why do (smart) people believe weird things? 4. Should all ideas and points of view, even those that are demonstrably false, be tolerated in a free society? Essential Reading Shermer, M. (2014) ‘Why people believe weird (http://www.michaelshermer.com/weird-things/excerpt/). things: excerpt’: Cohen, S. (2001) States of Denial: Knowing About Atrocities and Suffering (Cambridge: Polity), Ch.1,2,3. Oreskes, N. and Conway, E. (2010) ‘What’s Bad Science? Who Decides?’, in Merchants of Doubt (New York: Bloomsbury), pp.136-68. Further Reading Brockman, J. (ed) (2006) Intelligent Thought: Science Versus the Intelligent Design Movement (New York: Vintage Books) (see especially articles by Coyne, Dennett, Attran and Kauffman; and the Appendix on the judgment in the Kitzmiller vs. Dover Area School District case (223-56). Fine, R. and C. Turner (eds) (2000) Social Theory after the Holocaust, Liverpool University Press, esp. ch.2, Hannah Arendt: Politics And Understanding After The Holocaust, by Robert Fine (chapter 2 available online here: http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/sociology/staff/emeritus/robertfine/home/teaching material/sociologyofholocaust/ch2_fine_in_fine_and_turner_holocaust.pdf) Gilbert, D.T., Tafarodi, R.W. and Malone, P.S. (1993) ‘You Can’t Not Believe Everything You Read’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 65(2), pp.221-33. Goldacre, B. (2009) ‘Why clever people believe stupid things’, Bad Science (London: Harper Perennial), pp.242-55. P a g e | 19 Halbwachs, M. (1992[1925]) The Social Frameworks of Memory, in Lewis A. Coser (ed.), Halbwachs on Collective Memory (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), pp. 37-40, 74-83. Lipstadt, D. (1993) ‘The Antecedents’, in Denying the Holocaust: The Growing Assault on Truth and Memory (London: Penguin), pp.31-47. Lipstadt, D. (2005) History on Trial (New York: Harper Perennial). McGrath, A. (2005) ‘Proof and Faith’, in Dawkins’ God: Genes, Memes, and the Meaning of Life (Oxford: Blackwell), pp.82-118. Monbiot, G. (2008) ‘A Crusade Against Science’, Guardian (G2), 22 July 2008, pp7-11. Monbiot, G. (2006) ‘The Denial Industry’, in Heat: How to Stop the Planet Burning (London: Penguin), pp.20-42. Neisser, U. and Fivush, Robyn (1994) The Remembering Self: Construction and Accuracy in the Self-Narrative (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press). Available as e-book at http://webcat.warwick.ac.uk/record=b2524232~S1 Oreskes, N. and Conway, E. (2010) ‘The Denial of Global Warming’, in Merchants of Doubt (New York: Bloomsbury), pp.169-215. Oreskes, N. and Conway, E. (2010) ‘What’s Bad Science? Who Decides?’, in Merchants of Doubt (New York: Bloomsbury), pp.136-68. Shermer, M. (2007) Why People Believe Weird Things: Pseudoscience, Superstition, and Other Confusions of Our Time (New York: Souvenir Press). Shermer, M. and Grobman, A. (2002) Denying History: Who says the holocaust never happened and why do they say it? (Berkeley: University of California Press). Shermer, M. (2006) ’Science Under Attack’, in Why Darwin Matters: The Case Against Intelligent Design (New York: Henry Holt & Company), pp.89-105. Zerubavel, E. (2004) Time maps: collective memory and the social shape of the past. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press). P a g e | 20 Week 10: Making sense of suicide terror (Ed Page and Milena Kremakova) ‘Imagine a situation in which choosing to blow yourself up along with dozens of other people seems like a great idea. How bad must your life be if you think that it is better to be a sacrifice than to live, have a family, and be a productive member of society. Imagine what goes through the minds of people right before they become suicide bombers. Are they scared, are they angry, do they fully understand what they are about to do?’ (Bloom 2005: 1). This week, we take a closer look at a social phenomenon that raises profound questions for theories of explanation and interpretation: suicide terror. Researchers from a range of social science disciplines have attempted to explain, understand, and interpret suicide missions. Brainwashing, poverty, kin selection, pathology, organisation theory, coercion, cultural and game theory have all been used in this context and yet a sophisticated theory of suicide terror has yet to emerge. Here we explore a closer look at the nature, scope and historical antecedents of suicide terror in order to test the explanatory and interpretive power of alternative theories of social life. Seminar Questions 1. Do suicide bombers fully understand what they are about to do?Is ‘dying to kill’ ever be reasonable or rational? 2. What is the role of terrorist organizations in the execution of suicide missions? 3. To what extent can evolutionary psychology explain the behaviour of suicide bombers and the organisations to which they belong? Essential Reading Atran, S. (2003) ‘The Genesis of Suicide Terrorism’, Science 299, pp.1534-39. Elster, J. (2005) ‘Motivations and Beliefs in Suicide Missions’, in D. Gambetta (ed) Making Sense of Suicide Missions (Oxford: Oxford University Press), pp.233-58. Moghadam, A. (2006) ‘The Roots of Suicide Terrorism’, in A. Pedahzur (ed) (2006) Root Causes of Suicide Terrorism: The Globalization of Martyrdom (London: Routledge), pp.81-107. Further reading Bjorgo, T. (ed) (2005) Root Causes of Terrorism: Myths, Realities and Ways Forward (London: Routledge) (especially chapters by Ahmed and Merari). Bloom, Mia (2005) Dying To Kill: The Allure of Suicide Terror (New York: Columbia University Press), Ch.4 (pp.76-105). Elster, J. (2005) ‘Motivations and Beliefs in Suicide Missions’, in D. Gambetta (ed) Making Sense of Suicide Missions (Oxford: OUP), pp.233-58. Gambetta, D. (ed) (2005) Making Sense of Suicide Missions (Oxford: Oxford University Press), pp.259-99. Hafez, M.M. (2006) Manufacturing Human Bombs: The Making of Palestinian Suicide Bombers (Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace Press). Margalit, A. (2003) ‘The Suicide Bombers’, The New York Review of Books 50(1), pp.18. http://www.nybooks.com/articles/15979. P a g e | 21 Moghadam, A. (2006) ‘Suicide Terrorism, Occupation, and Globalization of Martyrdom’, Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 29, pp.707-29. Moghadam, A. (2006) ‘The Roots of Suicide Terrorism: A multi-causal approach’, in A.Pedahzur (ed) (2006) Root Causes of Suicide Terrorism: The Globalization of Martyrdom (London: Routledge), pp.81-107. Pape, R.A. (2006) Dying to Win: The Strategic Logic of Suicide Terrorism (New York: Random House).