View - TRAPCA

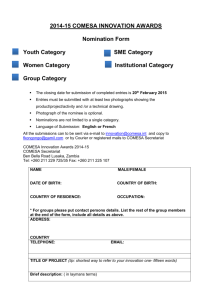

advertisement