Running head: INSTRUCTIONAL METHODS INSTRUCTIONAL

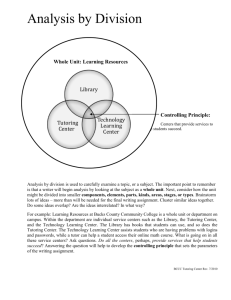

advertisement

Running head: INSTRUCTIONAL METHODS Instructional Methods Dylan Graves Virginia Commonwealth University 1 INSTRUCTIONAL METHODS 2 Introduction I teach math and social studies in a middle school. I co-teach three math courses and have one self-contained class. The social studies course is a functional class co-taught with another special education teacher. The class contains students with intellectual abilities as well as students with autism. In teaching the social studies class I became interested in how to educate the students in comprehension strategies that could be used in reading history texts. To have success in the class of social studies a student must be able to comprehend written material about the subject matter. I researched to find a teaching strategy that could be used with students with autism to help their reading comprehension abilities specific to the class of social studies that I could use in the classroom. The three math classes I co-teach have students with a wide range of abilities. I am interested in a strategy that can enhance student engagement and learning. Also in these sixth grade classrooms problem behaviors occur regularly. Graphic Organizers Research In the research article chosen the authors focused on improving the comprehension abilities of students with autism specifically in the area of social studies. Some unique challenges present themselves when a student with autism is learning social studies rather than English, however. The comprehension strategies used in an English or language arts class may not always transfer to use in the social studies class. One challenge for students with autism is learning the language of social studies, specifically the academic vocabulary associated with history (Zakas, Ahlgrim-Delzell, & Heafner, 2013). In order to teach the language of history the researchers turned to the use of graphic organizers. The study was designed to determine if the use of graphic INSTRUCTIONAL METHODS 3 organizers in a social studies classroom for students with autism would improve their comprehension abilities of a history passage. According to Gajria, Jitendra, Sood, & Sacks (2007) the use of graphic organizers had the largest effect on comprehension of expository text in students with learning disabilities. The researchers set out to determine if the use of graphic organizers would have a similar effect on students with autism in a social studies classroom. Methods The research team decided to use three middle school students to participate in the study. The three students all were diagnosed on the autism spectrum disorder, 11 to 15 years old, had good attendance, participate in the stat alternate assessment, were receptively fluent in English, could read a passage at a first or second grade level, and could provide a written response to questions (Zakas et al., 2013). The research design consisted of two parts. The first was the pre-teaching of use of the graphic organizer. As with many new teaching strategies it is important to pre-teach the concept, use, and specifics of the task. The intervention in the experiment did not occur until the students had learned how to use the graphic organizer. The team then conducted a series of scripted questions to give to the students to ascertain their knowledge and abilities in using the graphic organizer. The final part of the research study the researchers used a non-scripted expository text to test the student’s ability in using the graphic organizer to answer questions (Zakas et al., 2013). The researchers first modeled the use of the graphic organizer with pictures, which consisted of seven key history terms such as “event, people, location, sequence, and time” (Zakas et al., 2013). Once the students had learned the concept and proper usage of the graphic organizer the researchers moved ahead and assessed their abilities in the manner of scripted questions. Once the students had learned the new concept they would use the graphic organizer INSTRUCTIONAL METHODS 4 and the intervention would take place. The graphic organizer consisted of five blocks labeled event, location, time, people, first detail, second detail, third detail, and outcome (Zakas et al., 2013). The research study consisted of two dependent variables. The first was the number of correctly answered questions in response to the scripted questions. The students could score up to nine points (Zakas et al., 2013). The next dependent variable was the ability for the students to generalize the use of the graphic organizer and use it during unprompted sessions that involved the reading of a new passage (Zakas et al., 2013). A baseline was determined after the students used the graphic organizer with reading a passage for at least five times. The researchers then proceeded with each of the three students having five data points to use as a baseline. Results The research team found that all three students showed that they could use the graphic organizer independently with a new expository social studies text (Zakas et al., 2013). All three students used the graphic organizer with the new text without prompting its use. This shows that a graphic organizer can be used in social studies with effectiveness as well in an English classroom. Uses in Current Practice Being that I currently teach a middle school functional social studies class with students with autism this research study directly ties to my practice. The adaptive text used in the study is already being used by myself and my co-teacher. We must first model the use of the graphic organizer and then assess its use with our students. I believe this could be an essential tool to help my students comprehend history texts. INSTRUCTIONAL METHODS 5 The research study does have drawbacks, however. The researchers only assed the effectiveness of the graphic organizers with 3 students. There needs to be a larger sample size to see if the results can be generalized. The use of graphic organizers also has its challenges. The students will only be focusing on the big picture and main ideas missing many of the supporting details that are necessary for full comprehension. The use of graphic organizers in reading comprehension has been shown to be an effective intervention for students with disabilities (Gajria et al., 2007). I believe it can be used in a social studies classroom with effectiveness as well. This study only had three participants but I am confident that it can be replicated with a larger sample size. I think this intervention can be useful in my current social studies classroom. Peer Tutor Research This research study was concerned with the effectiveness of peer tutoring in learning basic math facts in an elementary school setting. The researchers looked at both reciprocal peer tutoring and nonreciprocal peer tutoring and evaluated their effectiveness (Menesses & Gresham, 2009). The team recognized there was no research study completed that looked at the possible differences in the effectiveness of reciprocal peer tutoring and nonreciprocal peer tutoring done in the same study. Furthermore, no research up until this point had been conducted using peer tutoring and a constant time delay procedure to teach basic math facts (Menesses & Gresham, 2009). INSTRUCTIONAL METHODS 6 Methods The study consisted of 59 total students, 32 boys and 27 girls, across 7 different classrooms. All of the students received general education services, however six of the students received small group instruction for reading (Menesses & Gresham, 2009). Each classroom was then administered a curriculum-based assessment (CBM) on the computer to determine their knowledge in a content area. The questions were made of two math facts that the students should have recently mastered, as reported by the teacher (Menesses & Gresham, 2009). The CBM probes were used to determine the fluency of math facts. The researchers used the probe over the course of three trials limiting bias (Menesses & Gresham, 2009). The study used three models for the classrooms. The first was a classroom using reciprocal peer tutoring, the second using nonreciprocal peer tutoring, and the third using standard classroom instruction (Menesses & Gresham, 2009). The standard classroom instruction was to not use peer tutoring for the duration of the study. The students were randomly assigned to one another within the classroom. The researchers then taught the students the method of the peer tutoring model using a tell, show, do approach (Menesses & Gresham, 2009). The student tutors would then perform a tutoring session with a researcher who would act as the tutee. The researchers would continue this instruction until all students reached a level of 100% accuracy over three trials. The researchers looked for us of six required tutoring behaviors to determine accurate use of the strategy. The behaviors included: begin when time is set, hold card up for 3 seconds, provide correction if necessary, provide praise, shuffle cards, and continue until timer rings (Menesses & Gresham, 2009). The students used peer tutoring 3 times a week until they had completed 15 INSTRUCTIONAL METHODS 7 sessions. The student groups used 10 cards each with one math fact on it. The sessions used a constant time delay (CTD) format, which required the tutor to wait 3 seconds for a response. After those three seconds if the tutee answered correctly he or she would be praised, if an incorrect answer was given the tutor would correct and move on to another card (Menesses & Gresham, 2009). The progress was assessed at the end of every tutoring session. At the close of every tutoring session the tutor would present ten math facts individually to the tutee using the same CTD method but without any verbal prompts or praise. The tutor would record the number of correct responses. Once the tutee provided correct responses for all ten cards on two consecutive occasions a new stack of ten cards was then used (Menesses & Gresham, 2009). All of the peer tutoring sessions were conducted in a separate, unused classroom with a researcher present monitoring the activity. Results The study shows that both the reciprocal peer tutoring group and the nonreciprocal peer tutoring groups performed better on the post tutoring assessment than the control group. When comparing the pre and post scores for the CBM the reciprocal peer tutoring group showed significant changes in the pre and post scores, as did the nonreciprocal group; the control group showed no significant changes in pre and post test scores, however (Menesses & Gresham, 2009). The researchers also compared the differences in results of the CBM measured in the posttest and follow up assessment. The follow up assessment was given three weeks after the posttest to determine math facts knowledge maintenance. The three groups (reciprocal peer tutoring, nonreciprocal peer tutoring, and control group) showed no significant changes in the outcome of post and follow up test (Menesses & Gresham, 2009). INSTRUCTIONAL METHODS 8 Uses in Current Practice The study shows that peer tutoring can be an effective strategy to use for students to master basic math facts. Both peer tutoring groups produced higher gains in the area of basic math facts than did the control group (Menesses & Gresham, 2009). This can be useful in my classroom when teaching 6th graders. Once the strategy of peer tutoring is modeled for the students they will be able to tutor each other in class. The students I work with have challenges in the area of basic math facts and this intervention may prove useful to help them learn. I am concerned, however, that the maintenance of the math facts did not occur after 3 weeks. I am also encouraged that the peer tutoring strategies can enhance student engagement, interest and promote positive behavior interactions within the classroom. This strategy can also help with behavior management in the classroom. I see the setting of the peer tutoring in the study as a potential drawback. The students were performing their peer tutoring activity in an enclosed room with a researcher present. This is an environment where the student is closely monitored so I believe problem behaviors are less likely to occur. If the peer tutoring activity is used in a regular classroom the results could prove to be different. INSTRUCTIONAL METHODS 9 Reference List Gajria, M., Jitendra, A. K., Sood, S., & Sacks, G. (2007). Improving comprehension of expository text in students with LD: A research synthesis. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 40, 210-225. Menesses, K. F., & Gresham, F. M. (2009). Relative efficacy of reciprocal and nonreciprocal peer tutoring for students at-risk for academic failure. School Psychology Quarterly, 24(4), 266-275. Zakas, T., Browder, D. M., Ahlgrim-Delzell, L., & Heafner, T. (2013). Teaching social studies content to students with autism using a graphic organizer intervention. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7(9), 1075-1086.