I Hear America Singing.

advertisement

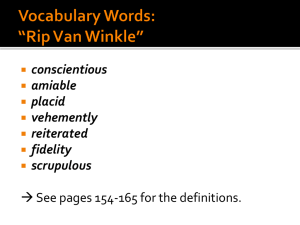

On Being Brought from Africa to America Critical Appreciation: "On Being Brought from Africa to America" is a short, but powerful, poem about slavery. "On Being Brought" is Wheatley's most anthologized poem. "On Being Brought" mixes themes of slavery, Christianity, and salvation. This poem addresses ideas of liberty, religion, and racial equality. The speaker says she was brought from a "Pagan" land and it was a good thing that she was brought from her homeland. Mercy brought her and it also "taught my benighted soul to understand that God exists, and God saves. The speaker says she never knew about redemption or that there was a God who could save her. And she wasn't searching for redemption either. Then she speaks about her race. She feels that some people has scornful attitude towards the black race. They are viewed as secondary because of their skin colour. Then she is equating the black people with all other Christians in the world. If Negroes are equal in God's eyes, then they should be considered equal in society. The last line of the poem refers to the speaker's spiritual awakening. Just as mercy enlightened her earlier in , allthe people of different races can be "refin'd and join th' angelic train. Rip Van Winkle 1. The actual author says this story was found in this man's papers after he died. • Nathaniel Hawthorne • Ralph Waldo Emerson • Diedrich Knickerbocker • Ambrose Bierce 2. What does Rip first notice is different when he approached the village after his nap? • There are more houses than before he slept. • His house is abandoned. • The inn has changed names. • He doesn't recognize people and the people are dressed differently. 3. What are the strangers playing when Rip Van Winkle first sees them in the amphitheatre? • darts • ninepins • football • soccer 4. How many years had Rip been asleep? • ten years • fifteen years • twenty years • thirty years 5. What was different about Rip's gun when he awoke? • It was missing. • The barrel was rusted; the stock was wormeate • The barrel was twisted; the stock missing. • It was buried nearby. 6. What made Rip Van Winkle fall asleep in the mountains? • He had hunted hard all day. • He had put in a hard day's work. • He had sampled the strangers' liquor. • He had hit his head while hunting. 7. What happened to Dame Van Winkle after Rip's disappearance? • She divorced him. • She declared him dead and remarried. • She moved from the area to start a new life. • She fell dead from a burst blood vessel after an altercation with a peddler. 8. What was the condition of Rip Van Winkle's farm? • It was falling apart and not much grows on it anymore. • It was the most prosperous in the area. • He grew more crops than any other farmer in the area. • He had bought his neighbor's farm to double the size of acreage. 9. What was Rip Van Winkle's one personality flaw? • He couldn't relax. • He couldn't carry on a conversation with anyone. • He was mean to his wife. • He would help everyone else before attending to his own business. 10. What was the name of Rip's dog? • Sparky • Fido • Coyote • Wolf 11. Who is the real author of this story? • Edgar Allan Poe • Washington Irving • Henry David Thoreau • Nathaniel Hawthorne 12. What happened to Rip's dog after Rip fell asleep? • He was eaten by wild animals. • He never left Rip's side and died beside him. • He returned to the village. • He was taken by Hendrick Hudson and the other strangers. 13. Which word would NOT describe Rip Van Winkle? • arrogant • simple • henpecked • goodnatured 14. What happened to Rip at the end of the story? • He returned to his home to live out the rest of his life as before. • He moved in with his daughter and her husband. • He built a cabin for himself and his dog high up in the mountains. • He moved into the hotel and became a partner in the business. 15. When Rip sees the first stranger, what is the stranger carrying? • a gun • a knife • a sword • a keg 16. What is the setting of this story? • the Rocky Mountains • the Smoky Mountains • the Grand Tetons • the Kaatskill Mountains 17. What important event in American history took place during Rip's sleep? The Revolutionary War • The Civil War • The Mexican War • The French & Indian War 18. What group of people had settled in Hudson Valley region? • German • Spanish • Dutch • Cuban 19. What are Rip and Dame Van Winkle's children like at the beginning of the story? • kind and gentle • quiet and shy • ragged and wild • smart and snobbish 20. What is NOT a physical change that Rip notices about himself after his "nap" • He is stiff in his joints. • His beard has grown a foot long. • He has lost his ability to hear. • His beard has turned gray. Philip Freneau was an ardent patriot who is still remembered as the "Poet of the American Revolution." Whitman (1819-1892) was one of the great innovators in American literature. In the cluster of poems he called Leaves of Grass he gave America its first genuine epic poem. The poetic style he devised is now called free verse that is, poetry with outa fixed beat or regular rhyme scheme. Whitman thought that the voice of democracy should not be haltered by traditional forms of verse. His influence on the poetic technique of other writers was small during the time he was writing Leaves of Grass but today elements of his style are apparent in the work of many poets. During the20th century, poets as different as Carl Sandburg and the "Beat" bard, Allen Ginsberg, have owed something to him. Whitman grew up in Brooklyn, New York I Hear America Singing. I hear America singing, the varied carols I hear, Those of mechanics, each one singing his as it should be blithe and strong, The carpenter singing his as he measures his plank or beam, The mason singing his as he makes ready for work, or leaves off work, The boatman singing what belongs to him in his boat, the deck- hand singing on the steamboat deck, The shoemaker singing as he sits on his bench, the hatter singing as he stands, The woodcutter's song, the ploughboy's on his way in the morning, or at noon intermission or at sundown, The delicious singing of the mother, or of the young wife at work, or of the girl sewing or washing, Each singing what belongs to him or her and to none else, The day what belongs to the day—at night the party of young fellows, robust, friendly, Singing with open mouths their strong melodious songs. I HEAR AMERICA SINGING INTRODUCTION There's no doubt about it: Walt Whitman (1819-1892) was the father of American poetry. The awesomeness of his poetry is rivaled only by his beard. Whitman, whose life and career spanned the nineteenth century, helped to define what it means to be an American. He loved his country. He loved the bustle of the cities and the expansiveness of the wilderness. He loved Abraham Lincoln and the fallen soldiers of the Civil War. He loved technology and industry and he loved the American promise of freedom. But most of all, Whitman loved the regular Joes of America, the guys and gals with regular jobs, living out their regular American dreams. Walt Whitman was as impressed by the life of an American shoemaker as he was of the life of Abraham Lincoln. The poet had some serious American pride, and he directed it toward everyone. Published in Whitman's 1860 edition of his epic collection Leaves of Grass, "I Hear America Singing" is all about this American pride. And it's specifically about pride in work. In the poem, Whitman describes the voices of working Americans toiling away at their jobs; he details the carpenter and boatman, the hatter and the mason, the mother and the seamstress alike. And by imagining that they are all singing, he celebrates them and their hard work, and also creates a vision of an America unified by song and hard work. For Whitman, the average Joe stone mason is just as important as the president of the U.S. of A. Now that's a vision of democracy we can get behind. The poet hears the "varied carols" of all the people who contribute to the life and culture of America. The mechanic, the carpenter, the mason, the boatman, the shoemaker, and the woodcutter all join in the chorus of the nation. The singing of the mother, the wife, and the girl at work expresses their joy and their feeling of fruition. These are highly individualistic men and women. Each person sings "what belongs to him or her and to none else." This poem underscores Whitman's basic attitude toward America, which is part of his ideal of human life. The American nation has based its faith on the creativeness of labor, which Whitman glorifies in this poem. The catalog of craftsmen covers not only the length and breadth of the American continent but also the large and varied field of American achievement. This poem expresses Whitman's love of America — its vitality, variety, and the massive achievement which is the outcome of the creative endeavor of all its people. It also illustrates Whitman's technique of using catalogs consisting of a list of people. "I Hear America Singing" is basically a joyful list of people working away. The speaker of the poem announces that he hears "America singing," and then describes the people who make up America—the mechanics, the carpenters, the shoemakers, the mothers, and the seamstresses. He declares that each worker sings "what belongs to him or her," and that they all sing loud and strong as they work. And as the poem ends, we learn that they like to sing at their parties, too. America: full of American Idol wannabes. Lines 1-2 I hear America singing, the varied carols I hear, Those of mechanics, each one singing his as it should be blithe and strong, Our speaker doesn't waste any time. He (and we can only assume it's a he at this point) jumps right into the poem with a bold declaration: "I hear America Singing." Let's just take a moment to acknowledge that the speaker's use of "America" here is figurative. It's not like New York is singing alto while Montana jumps in in a soprano voice. Nope, the word "America" is a symbol for American people more generally. But the "singing" is not figurative. This poem is literally about Americans singing songs. Or, in the speaker's words, "varied carols." The speaker acknowledges that Americans sing all different kinds of songs in all different kinds of voices. First up: the mechanics. Their voices are "blithe" (which means joyous) and strong. And the mechanics voices are as they "should be." The mechanics meet the speaker's expectations. Before we move on, let's be sure to take note of these very long lines. Whitman wrote in free verse, which means that his poems do not have regular rhymes or meter, or even regular line-lengths. In fact, these long, free verse lines are perhaps what ol' W.W. is best known for. As we will see as the poem continues, you can cram a whole lot of info into a Whitmanesque long line. (Check out "Form and Meter" for more on that style.) Lines 3-5 The carpenter singing his as he measures his plank or beam, The mason singing his as he makes ready for work, or leaves off work, The boatman singing what belongs to him in his boat, the deck-hand singing on the steamboat deck, In the second line of a poem, we learned about a mechanic singing. Here, we're introduced to four more singing Americans: a carpenter, a mason, a boatman, and a deck-hand. Starting to notice any similarities? These guys are all laborers. They're all at work. Even more specifically, they are manual laborers, who work with their hands. Not everyone can sing at work after all. If you are a lawyer making your case in court, you can't exactly burst out into a rousing chorus of "America the Beautiful," can you? We think not. The singing workers are all dudes who do tough manual labor—the carpenter making his measurements, the deck-hand ready to work on the steamboat deck. This is unglamorous work for sure, but through their singing, these laborers take joy in what they do. Note the sense of ownership in the poem; the mason is "singing his" song, while the boatman is "singing what belongs to him in his boat." These guys are proud of what they do. And the speaker is proud to acknowledge their work (and their awesome singing voices) in this poem. He's shedding some light on people who don't often make appearances in poetry (especially in nineteenth-century America). But we've got to ask a question: is the speaker painting a too-rosy picture of these workers? These can be dangerous jobs, after all. What is he leaving out of this picture? Let's read on to see… Lines 6-8 The shoemaker singing as he sits on his bench, the hatter singing as he stands, The woodcutter's song, the ploughboy's on his way in the morning, or at noon intermission or at sundown, The delicious singing of the mother, or of the young wife at work, or of the girl sewing or washing, Are you ready for more workers? We're ready for more workers. The next few lines of the poem cram in even more working dudes (and introduce some working ladies, too). Now we're got a shoemaker, a hatter, a woodcutter, a ploughboy, a mother, a young wife at work, a seamstress and washerwomen (whew). What do these peeps all have in common? They work hard for their money. And they all sing. By drawing together such different people doing different things, Whitman universalizes the issue of work. Whether you're old or young, black or white, woman or man, you need money to live. And how do you get money? By working. And how do you keep your spirits up by working? Singing, of course. And let's not forget that it may be necessary to keep those spirits up. The speaker acknowledges that the ploughboy works from "morning" to "sundown." This is a long day of hard labor, even if that ploughboy is singing his songs to pass the time. One particularly cool thing that Whitman does in this poem is that he acknowledges the work of women along with the manual labor of men doing "manly" jobs like woodcutting and plowing. The mother works, the young wife goes to work, the girls washes and sews. The world of labor is not just a man's world; Whitman celebrates the work of women—even the work of what we might now call the stay-at-home mom—in his poem. Neat-o. Before we move along, let's take note of Whitman's long lines again. They keep getting longer and longer. There's a sense of what we might like to call "overmuchness" in the poem. There are so many people that Whitman wants to celebrate that the lines of the poem can barely contain them all. Lines 9-11 Each singing what belongs to him or her and to none else, The day what belongs to the day—at night the party of young fellows, robust, friendly, Singing with open mouths their strong melodious songs. The poem ends by bringing all of these singing laborers together. They are "each singing what belongs to him or her and to none else." The speaker acknowledges that each of their laboring is unique, that their work belongs to themselves. And he even acknowledges that this is true of women too; note that "him or her." Sure, this may not be a big deal now, but let's remember that Whitman wrote this poem decades before women could even vote in the US. Small moments like these are progressive, and we like 'em. But as much as the speaker of the poem celebrates work, he acknowledges that there's a time for work and a time for play. The singing of the day is different than the singing of the night; the daytime singing is "what belongs to the day." At night, it's party time. And what happens at party time? Well, "the young fellows, robust, friendly," keep singing; they sing "with open mouths their strong melodious songs." Singing: it's a daytime and a nighttime activity in Whitman's America. It's one big, star-spangled sing-a-long—good times. But before we end our analysis, let's just think for a moment about what singing means in the poems. Sure, singing here is literal. These dudes and dudettes are literally singing as they chop wood and as they make hats and as they take care of the laundry. We know that this singing is for real. The speaker tells us about their "strong," "melodious," even their "delicious" voices. But singing also has a metaphorical aspect. Sure these laborers are singing songs to keep themselves occupied while doing physical work, but Whitman interprets this singing as a celebratory sign that these laborers love their jobs, love their grueling labor. And these workers love America too. But is this rosy view of labor Whitman's alone? Is he perhaps a little too enthusiastic about what it means to spend all day sewing or cutting wood? (We'd take poetry writing over masonry work any day of the week.) Whitman loved to think about those working guys and gals singing as they worked. He acknowledged the hard manual labor done by people who didn't often get recognized in poetry back in good ol' nineteenth-century America (or today, even). But was his perspective a little skewed? Do you think "I Hear America Singing" leaves a lot out of the story of the working American man and woman? We'll chew on these meaty questions in the rest of the "Analysis" section—click on over. 1. In what century did Walt Whitman live? -> eighteenth True False 2. What is Whitman most known for, other than his poetry? -> His voice True False 3. Who did Whitman memorialize in "O Captain! My Captain!" -> Abraham Lincoln True False 4. In the first line of "I Hear America Singing," what does the speaker actually hear America singing? -> "varied carols" True False 5. Other than singing, what are the good folks of this poem up to? -> Working True False Dickinson ranks with Whitman as the greatest of American poets. Her short poems are packed with meaning and technical achievement. She is a miniaturist in opposition to Whitman's more expansive lines. She deftly observes her religious faith and doubt, the meaning of life and death, her role as a woman, the relation of nature to culture, and literature to life. Summary[edit] The story of Rip Van Winkle is set in the years before and after the American Revolutionary War. In a pleasant village, at the foot of New York's Catskill Mountains, lives kindly Rip Van Winkle, a colonial British-American villager of Dutch ancestry. Van Winkle enjoys solitary activities in the wilderness, but he is also loved by all in town—especially the children to whom he tells stories and gives toys. However, he tends to shirk hard work, to his nagging wife's dismay, which has caused his home and farm to fall into disarray. One autumn day, to escape his wife's nagging, Van Winkle wanders up the mountains with his dog, Wolf. Hearing his name called out, Rip sees a man wearing antiquated Dutch clothing; he is carrying a keg up the mountain and requires help. Together, they proceed to a hollow in which Rip discovers the source of thunderous noises: a group of ornately dressed, silent, bearded men who are playing nine-pins. Rip does not ask who they are or how they know his name. Instead, he begins to drink some of their moonshine and soon falls asleep. He awakes to discover shocking changes. His musket is rotting and rusty, his beard is a foot long, and his dog is nowhere to be found. Van Winkle returns to his village where he recognizes no one. He discovers that his wife has died and that his close friends have fallen in a war or moved away. He gets into trouble when he proclaims himself a loyal subject of King George III, not aware that the American Revolution has taken place. King George's portrait in the inn has been replaced with one of George Washington. Rip Van Winkle is also disturbed to find another man called Rip Van Winkle. It is his son, now grown up. Dutch people playing nine pins(kegelen). Painted 1650-1660 by Jan Steen. Rip Van Winkle learns the men he met in the mountains are rumored to be the ghosts of Hendrick (Henry) Hudson's crew, which had vanished long ago. Rip learns he has been away from the village for at least twenty years. However, an old resident recognizes him and Rip's grown daughter takes him in. He resumes his usual idleness, and his strange tale is solemnly taken to heart by the Dutch settlers. Other henpecked men wish they could have shared in Rip's good luck and had the luxury of sleeping through the hardships of the American Revolution. Characters in the story of Rip Van Winkle[edit] Character Description Rip Van Winkle A henpecked husband who loathes 'profitable labor'. Meek, easygoing, never-do-well resident of the village who wanders off to the mountains and meets strange men playing ninepins. Dame Van Winkle Rip Van Winkle's cantankerous and nagging wife. Rip Van Winkle, Jr. Rip Van Winkle's ne'er-do-well son. Judith Gardenier Rip Van Winkle's married daughter. She takes her father in after he returns from his sleep. Derrick Van Bummel The local schoolmaster and later a member of Congress. Nicholas Vedder Landlord of the local inn where menfolk congregate. Van Schaick The local parson. Jonathan Doolittle Owner of the Union Hotel, the establishment that replaced the village inn. Wolf Rip's faithful dog, who does not recognize him when he wakes up Man carrying keg up the mountain explorer of the Hudson River. The ghost of Englishman Henry Hudson, Ninepin bowlers The ghosts of Henry Hudson’s crewmen from his ship, the Half-Moon. They share purple magic liquor with Rip Van Winkle and play a game of ninepins. Brom Dutcher Neighbor of Rip who went off to war while Rip was sleeping. Old woman Woman who identifies Rip when he returns to the village after his sleep. Peter Vanderdonk The oldest resident of the village. He confirms Rip’s identity and cites evidence indicating Rip’s strange tale is true. Mr. Gardenier Judith Gardenier’s husband, a farmer and crabby villager. Rip Van Winkle III Judith Gardenier. Rip Van Winkle’s infant grandchild. His mother is