DRAFT 1:1 Initiatives in North Carolina Schools A report by Callie

advertisement

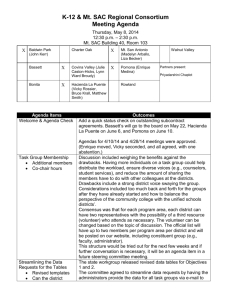

DRAFT 1:1 Initiatives in North Carolina Schools A report by Callie Uffman University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill B.A. English, Global Studies May 2013 DRAFT An Overview of Digital Learning Today’s “technology-fueled, knowledge-based economy” demands a work force that is equipped with the skills of digital literacy, and it is up to America’s schools to ensure students develop these skills. Traditional learning emphasizes the three R’s, helping students master the basic skills of writing, reading and arithmetic, and the soft skills of communication, collaboration, and creativity. But in order to be fully prepared to contribute to the 21st century work force, students must also learn skills of problem solving and innovation, and must “be adept at navigating virtual worlds.” Schools and postsecondary institutions must upgrade traditional teaching practices if they are to graduate work forceready students (Gordon 2011). Because the American education system was not designed to teach skills of digital literacy, Gordon argues, “we need to be more purposeful in embedding these kinds of skills into educational landscapes.” Schools must thoughtfully adapt to an increasingly technological landscape “if K-12 graduates are to thrive in the tech-infused job sectors they will enter upon graduation.” Don Knezek, CEO of the International Society for Technology in Education, describes the digital literacy skills that students need: These new skills that we call digital skills are simply cognitive skills in digital settings. Beyond being able to use technology efficiently and productively…K-12 graduates should understand how to use it to define and break down a problem, look into how similar problems have been solved, and design and implement a solution. In communicating that solution, they should be skillful not merely at typing a Word document but also at telling a compelling story through an interactive multimedia presentation. So, rather than merely learning how to use technology, students should learn old and new skills with technology. While many schools are introducing technological tools and have asked students to use digital media in assignments, few have taken the further step of creating digital learning landscapes. Eileen Lento of Intel notes, “too many districts invest in technology with neither a long-term vision for how it will be used nor any definition or measurement of success”. That long-term vision should include three levels of implementation: (1) teaching about technology use (2) embedding technology in instruction (3) teaching through technology, such as with simulations or augmented reality. Districts that focus too much on the first level, investing in technology with no implementation strategy, do not reap the benefits of a total technological transformation. Lento articulates the problem well: “What often happens, then, is computers are used as expensive pencils, and then they wonder why they're not getting different results” (Gordon 2011). Districts that invest in technology and strategically implement a transformation provide “the flexibility for kids to learn online, doing more project-based learning, and having teachers come together in an interdisciplinary way to create experiences that enable students to explore these digital technologies, while continuing to ensure that they have a rigorous academic experience.” Magner explains that the emphasis should be less on fixing 20th century schools and more on building 21st century schools” (Gordon 2011). North Carolina Policy Supports Digital Learning Transformation North Carolina has taken steps to build 21st century schools with its policies on digital learning. The 2011-2013 North Carolina State School Technology Plan by the Commission on School Technology outlines an implementation plan for using funds from the State School Technology Fund to improve digital learning in North Carolina schools. The plan’s priorities include improving LEAs’ infrastructure for technology and connectivity, providing universal access to digital learning devices, increasing use of digital textbooks, improving technology-enabled professional development, and positioning the state as a leader in 21st century learning practices (NC State School Tech Plan). In 2013, the North Carolina General Assembly has passed legislation to implement the State School Technology Plan and support digital learning in North Carolina schools. House Bill 23 commissions the University of North Carolina Board of Governors to “integrate digital teaching and learning into the requirements for licensure renewal” for teachers (House Bill 23). The bill requires all students in teacher education programs to demonstrate competencies in “using digital and other instructional technologies” so that they are prepared to “use digital and other instructional technologies to ensure provision of high-quality, integrated digital teaching and learning to all students” (House Bill 23). House Bill 23 was read and ratified on March 13, 2013. House Bill 44, entitled “Transition to Digital Learning in Schools,” allocates previous funding for textbooks to funding for digital materials, “to provide educational resources that remain current, aligned with curriculum, and effective for all learners by 2017” (House Bill 44). House Bill 44 was read and ratified on March 11, 2013. House bill 45 entitled “Internet Access for Public Schools” commissions the Department of Commerce to take an inventory of “infrastructure to support robust digital learning in the public schools and an inventory of internet access in all North Carolina counties” (House Bill 45). The Department will report its results and recommendations to expand access across the state by December 1, 2013 (House Bill 45). This bill is still undergoing the review process, but is scheduled to become effective on July 1, 2013. One-to-one initiatives In keeping with recent legislation and the North Carolina State School Technology Plan, many districts are implementing “one-to-one” initiatives to equip their schools with tools for 21st century learning. According to the State Technology Plan, one-to-one initiatives provide every student, teacher, and administrator in a district with a computing device. Formerly focusing on laptop computers, one-toone initiatives can also include programs that provide students, teachers, and administrators with mini laptops, tablets, and mobile devices. In 2008, more than 13,000 students in 28 LEAs in North Carolina participated in one-to-one initiatives. Schools implementing initiatives vary in size, location, and incomelevel (North Carolina Learning Technology Initiative). Perhaps the most acclaimed example of a successful one-to-one initiative is the Mooresville Graded School District. In 2007, Mooresville Superintendent Mark Edwards and the Mooresville Graded School District board adopted a six-year plan setting goals “for the utilization of technology resources in all classrooms, and focusing on academic achievement, engagement, opportunity and equity” (Cisco 2). Providing 6,000 laptops to students in grades 3-12 and faculty was a key part of Edwards’ strategy (EdWeek). Since 2008, the district has measured considerable improvement in assessments: the graduation rate increased from 80% in 2008 to 91 % in 2011, students meeting math, reading, and science proficiency standards increased from 73% in 2008 to 88% in 2011, and the district has the third highest test scores and second highest graduation rate in the state (New York Times). The Mooresville district made all of these improvements while spending only $7,415.89 per student, placing Mooresville at 100 out of 115 districts in the state in the spending per student metric. For his efforts and success, Dr. Mark Edwards was named the AASA 2013 Superintendent of the year. Edwards’ vision for 21st century education is key to Mooresville’s progress; he believes “that providing access to online tools is the key to creating a generation of informed, lifelong learners” (Cisco 1). The success of the Mooresville Graded School District’s one-to-one initiative in boosting student achievement demonstrates the capacity of districts to affordably integrate technology and improve their metrics of student success. An examination of one-to-one initiatives in five North Carolina LEAs reveals the benefits and challenges of one-to-one initiatives in districts of varying size, population, and location. One-to-one initiatives in North Carolina districts Fourteen North Carolina districts were contacted for this study and representatives from five districts responded to questions about their efforts to implement 1:1 initiatives. The following districts are featured for their leadership of digital learning in North Carolina: Mooresville Graded School District, Durham Public Schools, Wilkes County Schools, Rowan-Salisbury School System, and CharlotteMecklenburg Schools. 1. Mooresville Graded School District: The Mooresville Graded School District includes 5,409 elementary, middle, and high school students in Iredell County (Mooresville Statistics). Mooresville developed a strategic plan in 2007 and began implementing their digital conversion in 2008 (Mooresville Strategic Plan). The Mooresville Digital Conversion Initiative provided all employees with a 13” MacBook Air, students in grades 4-12 with an 11” MacBook Air, and every 3rd grade student with a 13” white Unibody MacBook. The initiative was funded primarily by redistributing funds from sources that were no longer needed, such as funding for traditional textbooks. The district installed the Cisco 802.11N to create a wireless network in all of their buildings, and trains students and parents on internet safety with lessons from Common Sense Media. Among the core values included in Mooresville’s strategic plan are (1) “Technology-enriched, relevant curriculum and effective delivery of the curriculum are foundations for addressing diverse 21st century learners;” (2) “21st century content…is integrated into core content areas;” (3) “All employees are treated as professionals and supported by sufficient resources and ongoing training designed to enhance and broaden skills that support the district vision, mission, and initiatives” (Mooresville Strategic Plan). Mooresville ensures that its employees are equipped to teach 21st century learners and use their digital devices effectively by including 8 early release days for professional development in their calendar and offering 2-3 summer training days. They also have technology support staff to update and repair devices, and “help desk” managers at 4 schools. While the Mooresville initiative has boosted student scores, attendance, and the district’s graduation rate, Chief Technology Officer Dr. Scott Smith counts the initiative a success for its role in helping students succeed. 2. Durham Public Schools: Durham Public Schools in Durham County includes 32,484 students. The district introduced a strategic plan for a 1:1 initiative in spring 2011, and since then has supplied students, teachers, and administrators with laptops and tablets. The initiative was funded by state and local funds and grants. The district offers wireless internet access in school buildings, and enforces student internet safety with local policy. Durham Public Schools offers teachers the following professional development opportunities to improve their familiarity with digital instruction: the New Schools Project, New Tech Network, and Apple training. Durham Public Schools has met the goals of their one-to-one initiative. 3. Wilkes County Schools: Wilkes County Schools serves over 10,000 students and employs nearly 700 teachers. The district gradually implemented their 1:1 initiative in four phases beginning in 2008, supplying all teachers with laptops and training. In 2009, students in grades 6 and 12 received laptops, and in 2010, students in grades 7 and 11 received laptops. In 2011, students in grades 8, 9, and 10 received laptops. In addition to laptops, many teachers have tablets, and students in grades 6-8 have netbook computers or mini laptops. Administrators have smartphones and tablets as well as laptops. The district received initial funding from grants, and has received sustaining funds through local capital outlay and additional grants. Wilkes County Schools offers wireless internet access in all Pre K – 12th grade buildings and classrooms, and uses Zscaler filtering to ensure internet safety. In addition, parents must sign COPPA forms for students under 13 before they may participate in Web 2.0 activities. The district uses ePals filtered student email accounts, and uses Edmodo and Learning Space as education social networking tools. Wilkes County Schools teaches online safety to students using iSafe resources. Since the first year of their 1:1 initiative, Wilkes County Schools has offered professional development opportunities for teachers. All teachers receive laptop 101 training and training in applications such as SAS Curriculum pathways, Edmodo, Google, and other Web 2.0 tools. Twelve Instructional Technology Facilitators provide initial training and sustaining support for teachers for the district’s 22 schools, and 10 technicians ensure that devices are updated and repaired. Wilkes County Schools has fully implemented the hardware portion of their 1:1 initiative. The district continues to offer professional development and resources to teachers as they change instructional practices to effectively utilize devices as learning resources. While the Wilkes County Schools district has successfully kicked off their 1:1 initiative, Associate Superintendent Wanda Hutchinson views the project as a work in progress as teaching methodologies adapt to 21st century learning. 4. Rowan-Salisbury School System: The Rowan-Salisbury School System serves over 20,000 students and nearly 1,500 teachers in Rowan County. The district introduced a strategic plan for their 1:1 initiative in 2008 with the goal of providing individual mobile devices to students. The plan initially targeted schools with low student achievement and has expanded to other schools in the district. Teachers, students, and administrators in RowanSalisbury schools have access to iPads, iPod touches, and laptop computers. Administrators have access to smartphones. The Rowan-Salisbury Schools initiative was funded with a combination of grants, state, local, and federal Title I funds, and PTA and fundraising events. The Blanche and Julian Robertson Family Foundation and Golden LEAF Foundation have made significant contributions to grant funding for the initiative. The Rowan-Salisbury School System offers wireless internet access in all district school buildings, and teaches internet safety to teachers and staff. The district provides internet filtering for students and staff with network appliances and software. Since it began in 2008, the initiative has included a professional development component, providing teachers with a minimum 2-day training session that focuses on how to effectively teach the curriculum using digital devices. The professional development opportunities give teachers ideas and projects that they can integrate into their teaching immediately, and gives them skills they need to successfully include digital devices in their instruction. In order to ensure devices are updated and repaired, every school in the system has an Instructional Technology Facilitator, and has nine district technical support employees on staff. Rowan-Salisbury Schools considers their 1:1 project a great success. The district has seen improvements in student proficiency on End of Course state tests. The graduation rate has increased and disciplinary problems have declined. Moreover, teachers report increased student engagement in 1:1 classroom environments. The following graph displays the increase in proficiency on End of Course state tests among Rowan-Salisbury students from 2008 to 2011. 70.0% 60.0% 50.0% 40.0% 2008-2009 30.0% 2010-2011 20.0% 10.0% 0.0% All students African-American Economically disadvantaged 5. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools: Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools serves over 135,600 students and employs over 8,960 teachers. In the spring of 2012, the district introduced a guest wireless network to support the rollout of digital devices. Approximately 4,000 student iPads and over 400 teacher iPads were initially deployed, and to date, the district has purchased nearly 6,500 iPads. In addition to providing wireless access and the introducing digital devices, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools launched the “Bring Your Own Technology” (BYOT) initiative in the fall of 2012. The initiative allows students and teachers to bring personal devices to use during the instructional day by connecting to the guest wireless network. Personal devices accessing the network include smartphones, laptops, mini PCs, iPads, iPods, and tablets. The network is filtered for students separately from the main CMS network. Currently, 1/3 of CMS schools have “good coverage,” allowing 30 devices in a classroom internet access. The district has plans to upfit all schools with good coverage by fall 2013. The district’s initiatives are funded by state technology funds, Federal Race to the Top and Title I funding, and local funds. Student internet access in Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools is filtered using the Websense tool, which blocks inappropriate websites and content. Gaggle, the student email solution, filters content and is a human monitored system that flags inappropriate content and notifies staff when intervention is necessary. Students are required to take a digital citizenship course through Gaggle and must sign the CMS Acceptable Use policy before accessing the student network. The district is developing a social media policy for staff and students. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools offers professional development and technical support for their digital learning initiatives. The Instructional Technology department supports teachers’ learning on topics from technology integration, best practices, classroom management, various applications, management of devices, blended learning, and the flipped classroom. The district support staff supports workstations and district-owned digital devices. In addition, each school has a trained Apple administrator to maintain iPads, and a technology contact to manage workstation, printer, and network issues. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools has few schools at the 1:1 ratio, but is currently piloting programs in the West corridor’s “Project Lift” schools. “Lift Zone” schools have a 1:1 ratio for grades K-5. This spring, students have been allowed to bring devices home. According to Chief Information and Transformation Officer, Dr. Valerie Truesdale, this pilot year will determine how the district will grow the 1:1 initiative. NC District 1:1 Initiatives District Students Year Devices Mooresville Graded School District Durham Public Schools 5,409 2008 32,484 2011 Wilkes County Schools 10,374 2008 RowanSalisbury Schools 20,460 2008 CharlotteMecklenburg Schools 135,600 2012 Grades 4-12: 11“ MacBook Air Grade 3: White Unibody MacBook Employees: 13” MacBook Air Laptops Tablets Teachers: laptops and tablets Grades 9-12: laptops Grades 6-8: mini laptops Administrators: laptops, smartphones, tablets iPads, iPod touches, laptops for students, teachers, and administrators Smartphones for administrators 4,000 student iPads, 400 teacher iPads Student, teacher personal devices allowed, including smartphones, laptops, mini PCs, iPads, iPods, and tablets Funding Home Access Redistribution of funds from traditional textbooks Yes; students in grades 4-12 Grant, state, local funding Not at this time Initial grant funding; Sustaining funds supplied through local capital outlay & grants Yes; students in grades 9-12 Grants; state, local, federal Title I funds; PTA & fundraising events Access to mobile devices on a limited basis State technology funds; Federal Race to the Top and Title I funds; local grant funding Not at this time Analysis & Conclusions The benefits of one-to-one initiatives are clear; districts that are committed to transforming to digital learning report higher scores, fewer disciplinary problems, and increased student engagement. An overview of five North Carolina districts’ efforts to implement one-to-one initiatives reveals several key practices that districts of all sizes and locations follow, and factors that vary by district. Key Practices All five districts, differing in size and location, included the following practices in their one-toone initiative: (1) Strategic Plan: All districts implemented their 1:1 initiative as part of a larger strategic plan for technology. Though they introduced programs differently, all districts followed a planned method for introducing digital devices in schools. (2) Professional Development: All districts complemented digital devices with professional development opportunities for teachers and administrators, as well as technical support for schools. Ensuring that teachers could effectively teach with devices was a priority of all five districts. (3) Wireless internet access: All districts provided or had plans to provide schools with wireless internet access. Schools using digital devices need internet access in order to use tools effectively. (4) Student internet safety: All districts used internet filtering to ensure student internet safety according to the Children’s Internet Protection Act. Several districts also required students to complete internet safety training before using the school-sponsored network and devices. Factors that Varied by District (1) Implementation timeline/Rollout plan: While all districts followed an implementation plan for their initiatives, the timeline and structure of the plan varied by district. While the Mooresville district introduced most devices in a single year, Wilkes County Schools introduced devices in phases over a four-year period. (2) Devices: The actual devices that districts chose to use varied greatly by district. While Wilkes County and Mooresville focused on providing students, teachers, and administrators with laptops, Charlotte-Mecklenburg supplies students and teachers with iPads and allows students to bring their own devices. (3) Funding sources: Districts’ initiatives differed in their sources of funding. While most initiatives were funded by some types of grant and state and local funding, the sources of the grant varied by district. The Rowan-Salisbury School System used funds from PTA and fundraising events to support their efforts. All districts combined various types of grants in a “funding package” for their one-to-one initiative. In conclusion, all five districts followed certain key practices in implementing their one-to-one initiatives, though their implementation timeline, devices provided, and funding packages varied. These districts’ efforts reveal that it is neither the devices nor the funding that determines the benefits and challenges of digital learning; it is the thoughtful introduction of digital learning tools and careful measurements of their effect. Eileen Lento of Intel considers a “long-term vision for how [technology] will be used” and the definition and measurement of success to be critical factors in digital learning transformations (Gordon 2011). The five districts’ strategic implementations of digital learning tools demonstrate how 1:1 initiatives can improve scores and student engagement. While improved metrics are worth celebrating, of the Mooresville district’s digital transformation, Chief Technology Officer Dr. Scott Smith notes, “It is not about the 1:1; it is about helping all students succeed.”