thesis in full - Royal Holloway

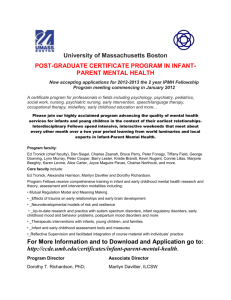

advertisement