Race Census Aff – MAGS - University of Michigan Debate Camp Wiki

advertisement

Race Census Aff – MAGS

Compiled by Lenny Brahin

Jaden Lessnick

Jillian Gordners

Brian Roche

1AC

The census has always been a powerful means of state surveillance—from

its very inception, census-taking has been a means to maintain a violent

social order

Mezey, 3 – Professor of Law at Georgetown University (Naomi, “Erasure and

Recognition: The Census, Race and the National Imagination”, 97 Nw. U. L. Rev. 17011768 (2003) Northwestern University Law Review, 2003)//jml

The Power to Discipline But power, needless to say, is at once affirmative and repressive, and the power

of enumeration is no exception. Even to the extent it fulfilled its purpose of documenting American excep- tionalism

and fueling the national imagination, the census did so partly by implicit and explicit reference to

outsiders and others, by identifying and exercising authority over the more

undesirable and unproductive citizens and non-citizens. Official statistics (and most

social and economic statistics are official in the sense that they are gathered by the state) are generally compiled by

means of a census, and early census-taking began as a method of surveil- lance,

conscription, tax assessment, manners control, and exclusion of un- wanted elements.71 The pre-modern census was,

as Paul Starr contends, "unambiguously an instrument of state power and social control ."72 While

Starr maintains that modem censuses have replaced coercion with coopera- tion, I suggest that even in the heady days of nineteenth

century America, where statistics and state-building made a giddy pair, there

remained an as- pect of social

control to the enterprise of numbering the people, and indeed, there remains such an

aspect today.73 This was especially evident when it came to naming and numbering by

race. How the modern census functions as an exercise of state disciplinary power and

social control requires expla- nation. One subtle aspect of social control made possible by

statistics was the creation of the idea of "the average person" and its corollary, the

deviant. Thus, statistics introduced two mutually dependent and thoroughly modem

concepts: the norm and deviance. Ian Hacking, in his remarkable book, The Taming of Chance, argues that

statistics gave rise to more than new concepts; they ushered in epistemological change as well.74 Hacking identi- fies what he calls

the "avalanche of numbers" at the beginning of the nine- teenth century as the beginning of a profound change in the way Americans

and Europeans thought about people, an epistemological shift away from the prevailing belief in determinism and causality to the

modem idea of probability and the laws of chance.75 The

laws of chance, unlike the preced- ing laws of

nature, emerged from the gathering of statistics of large popula- tions. "The imperialism

ofprobabilities could occur only as the world itself became numerical."76 But this new kind of information, in addition to pro- viding

sound bites for a growing empire, also occasioned a new kind of so- cial control.77 Society became statistical. A new

type of law came into being, analogous to the laws of nature, but pertaining to people. These new laws were expressed in terms of

probability. They carried with them the connotations of normalcy and of deviations from the norm. The cardinal concept of the

psychology of the Enlightenment had been, simply, human nature. By the end of the nineteenth century, it was being replaced by

something different: normal people."

Specifically, racial categorization on the census is used to maintain a

colonial order of racial exclusion

Kertzer and Arel, 2 - * PhD, Paul Dupee, Jr. University Professor of Social Science,

Professor of Anthropology, and Professor of Italian Studies at Brown University **PhD,

Associate Professor of Political Science and Chair of Ukrainian Studies at the University

of Ottawa, Canada (David and Dominique, “Census and Identity: The Politics of Race,

Ethnicity, and Language in National Censuses,” 2002)//jml

State modernity and the impetus to categorize The

significance of official state certification of collective

identities through a variety of official registration procedures can be gleaned by

contrasting these government efforts with the situation that existed be- fore such

bureaucratic categorization began. Collective identities are, of course, far from a recent innovation in human

history. However, before the emergence of modern states, such identities had great fluidity

and im- plied no necessary exclusivity. The very notion that the cultural identities of populations mattered in

public life was utterly alien to the pre-modern state (Gellner 1983). That state periodically required some

assessment of its population for purposes of taxation and conscription, yet remained

largely indifferent to recording the myriad cultural identities of its sub- jects. As a result, there was little

social pressure on people to rank-order their localized and overlapping identities. People

often had the sense of simply being “from here.” The development of the modern state, however, increasingly

instilled a resolve among its elites to categorize populations, setting boundaries, so to speak,

across pre-existing shifting identities. James Scott refers to this process as the “state’s attempt

to make a society legible,” which he regards as a “central problem of statecraft.” In order to

grasp the complex social reality of the society over which they rule, leaders must devise a means of radically

simplifying that reality through what Scott refers to as a “series of typifications.” Once these are made,

it is in the interest of state authorities that people be understandable through the

categories in which they fall. “The builders of the modern nation-state,” Scott writes, “do not

merely describe, observe, and map; they strive to shape a people and landscape that will fit these

techniques of observation” (1998:2–3, 76–77, 81). The emergence of nationalism as a new

narrative of political legitimacy required the identification of the sovereign “nation” along

either legal or cultural criteria, or a combination of both. The rise of colonialism, based on the denial that the

colonized had political rights, required a clear demarcation between the settlers and the

indigenes. The “Others” had to be collectively identified. In the United States, the

refusal to enfranchise Blacks and native Americans led to the development of racial

categories. The categorization of identities became part and parcel of the legitimating

narratives of the national, colonial, and “New World” state. States thus became

interested in representing their population, at the aggregate level, along identity

criteria. The census, in this respect, emerged as the most visible, and arguably the most politically

impor- tant, means by which states statistically depict collective identities. It is by no means the sole

categorizing tool at the state’s disposal, however. Birth certificates are often used by states to compile statistics on the ba- sis of

identity categories. These include ethnic nationality (a widespread practice in Eastern Europe); mother tongue, as in Finland and

Quebec (Courbage 1998: 49); and race, in the United States (Snipp 1989: 33). Migration documents have also, in some cases,

recorded cultural iden- tities. The Soviet Union, for instance, generated statistics on migra- tion across Soviet republics according to

ethnicity. The US Immigration Service, from 1899 to 1920, classified newly arrived immigrants at Ellis Island according to a list of

forty-eight “races or peoples,” gener- ally determined by language rather than physical traits (Brown 1996).

The categorization of racial identity on the census demands a static

recognition based in the politics of state surveillance to crowd out

alternative conceptions of cultural identity based in hybridity and mutuality

Torres 99 (maría de los Angeles. Maria is the director and professor of Latin American

and Latino Studies at the University of Illinois in Chicago, she has a PhD in Political

Science from the University of Michigan, “In the land of mirrors: Cuban exile politics in

the United States,” University of Michigan Press, 1999. pp. pp. 188-189, LB)

Furthermore. although these home countries were not direct colonies of the United States (with While rooted in the experience of

slavery, ideas

about race have affected conceptions of nationality as well. People of certain

nationalities, Latin Americans included, are often not considered white (the exception of Puerto

Rico), they do share some of the same dynamics of European countries and their colonies.

The United States essentially took over the postcolonial relationship between Europe and its others in the southern part of the

Western hemisphere. This

economic and political relationship is accompanied by a conceptual

framework that sees Latin America and Latin Americans as others. At the turn of the century U.S.

views of Latin Americans were blatantly racist. While such images have given way to more

sophisticated portrayals of Latin Americans, they are still influenced by these

perspectives. Once in the United States, emigres from Latin America live and work in a society

that has often excluded people of different cultures from full participation through a

process of racialization. Unlike European societies, the United States had legalized slavery, along with which came a

racist conception of who was entitled to participate in the public sphere. Racism permeated society.5 . For example,

government forms ask applicants whether they are white, black, or

Hispanic. "Hispanic"-an ethnic category-is equated conceptually with the

racial categories of "white" and "black." While color is a concept that was

part of the language of colonization, in the United States, it has unique elements that

influence the way that exclusion and, consequently, struggles for inclusion

have been waged. 6 Yet, instead of challenging the categories themselves as

exclusionary practices, many of the empowerment movements of the 1960s reproduced

the same categories, albeit in a positive light. Race, ethnicity, and gender were exalted as essential elements in

defining one's identity. For immigrant communities, these movements sought a reconnection to their

cultural roots, a notion which suggested a return to a lost territory. In the past ten years rigid

categories have given way to more complex understandings of ethnic and cultural identity. Curiously, some of these new ways of

looking at identity are not direct responses to exclusionary categories of race and culture but, rather, a response to categories

promoted by progressive movements that, in trying to develop a discourse of inclusion, promoted exclusionary categories

themselves. As such, the conceptual paradigms were not transformed but applied differently. In

the 1990s intellectuals,

particularly artists and writers, began proposing more complex ways of understanding

multiple identities and multiple points of cultural and political references that inform

the postmodern experience and that have been particularly evident in communities

made up of large numbers of immigrants. 7 There is a rich intellectual tradition in Latin America that can

contribute to these debates. Unlike the British, whose settlement patterns led colonial societies to create rigid categories of insider

and outsider (note the "one drop of blood" rule), the Spanish relied on armies to implement colonialism. In addition, the military

was accompanied by Catholic missionaries who believed that, if converted, natives could be considered full human beings. As a

result, in the Spanish colonies there was more intermingling of different peoples and a more flexible view of blending than in the

British colonial tradition. Mestizaje and syncretism have long been accepted as contributing to the formation of Latin American

identity. 8 There

is an important debate about identity issues taking place in postcolonial

Europe that can enrich the American debate. 9 One perspective that can be discerned from both is the need to

understand cultures and, consequently, identities both as hybrids and as ongoing processes. In diaspora communities

in particular the transculturation, or practice of clearly identifiable multiple cultures

previously conceived as homogeneous (home and host cultures), produces new forms of cultural

practices that can best be described as hybrid. In contrast to a paradigm that sees these cultures as proof of

cultural diversity, Homi Bhabha suggests that they demonstrate the hybridity of cultures themselves. This may open the

way "to conceptualizing an international culture based not on exoticism of

multiculturalism or the diversity of cultures, but on the inscription and articulation of

culture's hybridity" and in politics as a place "not located in any particular geographic

space, nor ... tied to a single predetermined political position."

This hybridity is polyculturalism, the recognition that racial and cultural

categories are not only socially constructed but also historically intertwined

such that their state categorization is nothing but an arbitrary imposition of

power. A polycultural understanding of race is a necessary check on

colonial racism

Prashad 2011 (vijay, director of the international studies program at trinity college,

everyone was kung fu fighting: afro-asian connections and the myth of cultural purity,

project muse, LB)

This "racism with a distance" ignores our mulatto history, the long waves of linkage that

tie people together in ways we tend to forget. Can we think of "Indian food" (that

imputed essence of the Indian subcontinent), for example, without the tomato (that fruit first

harvested among the Amerindians)? Are not the Maya, then, part of contemporary "Indian culture"?

Is this desire for cultural discreteness part of the bourgeois nationalist (and bourgeois diasporic)

nostalgia for authenticity?5 In search of our mulatto history, there is no end to the kinds

of strange connections one can find. Of course, these links are only "strange" if we take for

granted the preconceived boundaries between peoples, if we forget that the notion of

Africa andAsia, for instance, is very modern and that people have created cross-fertilized

histories for millennia without concern for modern geography. The linguistic ties across the

Indian Ocean, for example, obviate any attempt to say that Gujarat and Tanzania are

disconnected places: Swahili is the ultimate illustration [End Page 52] of our mulatto history, or what

historian Robin Kelley so nicely called our "polycultural" history.6 Bloodlines, biologists now show us, are not

pure, and those sociobiologists who persist in the search for a biologically determined

idea of race miss the mark by far.7 "So-called ‘mixed-race' children are not the only ones

with a claim to multiple heritages. All of us, and I mean ALL of us," Kelley argues, "are the

inheritors of European, African, Native American, and even Asian pasts, even if we can't

exactly trace our blood lines to all of these continents."8 Embarrassed by biological racialism, many

scholars turn to culture as the determinant for social formations (where communities

constructed on biological terms now find the same boundaries intact, but as cultural

ones). Of course centuries of racism have in reality produced racial communities, so that

"race" is indeed a social fact today. But cultural formations are not as discrete as is often

assumed, a revelation that gives rise to notions such as hybrid, which retains within it

ideas of purity and origins (two things melded together).9 Rejecting the posture of racism with a distance, Kelley

argues that our various nominated cultures "have never been easily identifiable, secure in their

boundaries, or clear to all people who live in or outside our skin. We were multi-ethnic

and polycultural from the get go."10 The theory of the polycultural does not mean that

we reinvent humanism without ethnicity, but that we acknowledge that our notion of

cultural community should not be built inside the high walls of parochialism and

ethnonationalism. The framework of polyculturalism uncouples the notions of origins and

authenticity from that of culture. Culture is a process (that may sometimes be seen as a thing), which

has no identifiable origin, and therefore no cultural actor can, in good faith, claim

proprietary interest in what is claimed to be his or her authentic culture. "All the culture

to be had is culture in the making," notes anthropologist Gerd Baumann. "All cultural differences are acts of

differentiation, and all cultural identities are acts of cultural identification."11 Multiculturalism tends toward a

static view of history, with cultures already forged and with people enjoined to respect

and tolerate each cultural world. Polyculturalism, on the other hand, offers a dynamic

view of history, mainly because it argues for cultural complexity, and it suggests that our

communities of the present are historically formed [End Page 53] and that these

communities move between the dialectic of cultural presence and antiracism, between a

demand for acknowledgment and for an obliteration of hierarchy. Bruce Lee's polycultural world

sets in motion an antiracist ethos that destabilizes the pretense of superiority put in place by white supremacy.

Polyculturalism accepts the existence of differences in cultural practice, but it forbids us

to see culture as static and antiracist critique as impossible.

No moral order is possible while racism is tolerated—ethics are

meaningless without a prior rejection of it

Memmi 2K (Albert, Professor Emeritus of Sociology @ U of Paris, Naiteire, Racism, Translated by Steve Martinot, p. 163165)

The struggle against racism will be long, difficult, without intermission, without

remission, probably never achieved. Yet, for this very reason, it is a struggle to be

undertaken without surcease and without concessions. One cannot be indulgent

toward racism; one must not even let the monster in the house, especially not in

a mask. To give it merely a foothold means to augment the bestial part in us and in

other people, which is to diminish what is human. T o accept the racist universe to

the slightest degree is to endorse fear, injustice, and violence . It is to accept the

persistence of the dark history in which we still largely live. it is to agree that the outsider will always be a possible victim (and which

man is not himself an outsider relative to someone else?. Racism

illustrates, in sum, the inevitable negativity

of the condition of the dominated that is, it illuminates in a certain sense the entire human condition. The anti-racist

struggle, difficult though it is, and always in question, is nevertheless one of the prologues to the ultimate passage from animosity to

humanity. In that sense, we cannot fail to rise to the racist challenge. However, it remains true that one’s moral conduit only

emerges from a choice: one

has to want it. It is a choice

among other choices, and always debatable in its

foundations and its consequences. Let us say, broadly speaking, that the choice to conduct oneself morally is the condition for the

establishment of a human order, for which racism is the very negation. This is almost a redundancy.

One cannot

found a moral order, let alone a legislative order, on racism, because

racism signifies the exclusion of the other , and his or her subjection to violence

and domination. From an ethical point of view, if one can deploy a little religious language, racism is ‘the truly

capital sin. It is not an accident that almost all of humanity’s spiritual traditions counsels respect for the weak, for orphans,

widows, or strangers. It is not just a question of theoretical morality and disinterested commandments. Such unanimity in the

safeguarding of the other suggests the real utility of such sentiments. All things considered, we

have an interest in

banishing injustice, because injustice engenders violence and death. Of course, this is debatable.

There are those who think that if one is strong enough, the assault on and oppression of others is permissible. Bur no one is ever

sure of remaining the strongest. One day, perhaps, the roles will be reversed. All

unjust society contains within

itself the seeds of its own death. It is probably smarter to treat others with respect so that they treat you with respect.

“Recall.” says the Bible, “that you were once a stranger in Egypt,” which means both that you ought to respect the stranger because

you were a stranger yourself and that you risk becoming one again someday. It is an ethical and a practical appeal—indeed, it is a

contract, however implicit it might be. In

short, the refusal of racism is the condition for all

theoretical and practical morality because, in the end, the ethical choice commands

the political choice, a just society must be a society accepted by all . If this

contractual principle is not accepted, then only conflict, violence, and destruction will be

our lot. If it is accepted, we can hope someday to live in peace . True, it is a wager, but the

stakes are irresistible.

Hence the plan: The United States Federal Government should eliminate

racial categorization on the United States Census.

Total elimination of racial categories on the census is necessary—reform

isn’t enough

CAPLAN 2012 (Arthur Caplan is head of the division of medical ethics at New York University's Langone Medical Center,

“Time to drop racial categories in census,” Chicago Tribune, August 16, http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2012-08-16/site/ctpersepc-0816-race-20120816_1_racial-categories-race-and-ethnicity-questions-quadroons)

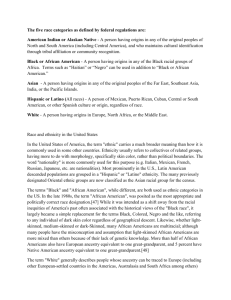

The U.S. Census Bureau announced that it wants to make a number of changes in how it counts

membership in a race. The change is based on an experiment the bureau conducted during the last census in which nearly

500,000 households were given forms with the race and ethnicity questions worded differently from the traditional categories. The

results showed that many people who filled out the traditional form did not feel they fit within the five government-defined

categories of race: white, black, Asian, Pacific Islander and American Indian/Alaska Native. If Congress approves, the bureau says it

plans to stop using the word "Negro" as part of a question asking if a person was "black, African-American or Negro." There are a

number of other changes planned for counting Hispanics and Arab-Americans.

These changes may seem like improvements. They are not. The bureau and Congress ought to

be considering a more radical overhaul of the census — dropping questions about race entirely. There

are a lot of reasons why.

First, the concept of "race" makes no biological sense. None. The classifications Americans use to divide people into

groups and categories have nothing to do with genetics or biology.

The notion that there is a black genome or an Hispanic genome or a Native American genome is ludicrous. There is tremendous

variation in the genomes of the most common racial categories used in America. Think about it — what is the biological basis for the

Asian category? There is far more in common genetically between the Census Bureau's racial groups than there are differences. If

advances in genetics have shown us anything since the mapping of the human genome 15 years ago it is that there is zero overlap

between the terms the census is using and biology.

Worse, the

terms are the product of nothing but racism. The old "one-drop" rule continues

to apply in how many people divide whites from blacks — any black ancestry makes you black.

Remember the old days of quadroons and mulattos — the racism that inspired these racial categories simply became unacceptable in

American society? Nothing changed about biology.

Who is a Native American? A person who may be of mixed ancestry who may look anything but stereotypically Native American but

who speaks a tribal language and holds a high office in a tribal government? Is

there any reason other than racism

to lump together Hispanics as a class that captures anything significant except a

connection to Spanish and Spanish colonialism?

Consider how other parts of the world with very different histories than ours think about racial categories. India has all manner of

divisions of its people that would never even occur to an American. When the British controlled India they introduced a whole

scheme of "races" based upon the assumption that certain groups were more warlike and combative than others. They divided the

entire spectrum of Indian ethnic groups into two categories: a "martial race" and a "nonmartial race." Dogras, Gurkhas, Garhwalis,

Devars, Sikhs, Jats and Pashtuns were the martial races — as it turns out they were also the groups who were initially more accepting

of British rule. The

everyday classification of racial groups in the Balkans, Africa, China,

Japan, Mexico, Brazil and South Africa (pre- and post-apartheid) shows that what we think of as

natural racial divisions are not seen that way in other countries. By using our race

categories decade after decade, the Census Bureau reinforces categories that are nothing

more than the results of a racism-tainted tale of who got to America first and who

followed — combined with a hefty dollop of 18th-century European colonialist thinking.

The attempt to put everyone into a totally fabricated, socially constructed box also means that the growing number of mixed-race

Americans have to make a choice or become "other." Even President Barack Obama is described as black when

Why force the notion of

mixed race on anyone much less let it be an accepted part of government policy?

there is no reason he could not be classified as white but for the racist past of the country he was born in.

The lobby to keep race as a key driver in the census is powerful. Many see their jobs and futures tied to resources that are allocated

by race. Others

fear a loss of identity if racial categorizations are allowed to erode. They are

wrong.

India did away with divisive, historically racist, racial categories in its census in 1951. It

is time for Congress to tell the Census Bureau to do the same.

There is no alternative to state engagement—we have to engage the policy

details of the census to confront racist violence

Thompson, 10 – PhD candidate (poli sci) at University of Toronto (Debra Elizabeth,

“Seeing Like a Racial State: The Census and the Politics of Race in the United States,

Great Britain and Canada” A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for

the degree Doctor of Philosophy Department of Political Science, 2010)//jml

A more focused lens is necessary in order to examine how policy-makers propose and

evaluate alternatives and come to decisions about the methods that will be employed in

the enumeration of the multiracial population. Though the census is a racial

project, it is also a policy sphere, inhabited by elites, bureaucrats, “experts,”

data users, academics, interest groups, and members of the public. These conceptualizations of

the census are not mutually exclusive. As a racial project the census connects

meanings of race – meanings which, I have argued, often exist beyond national boundaries – with different means of

(racially) organizing societies. I contend that the organization of race occurs through census

policy schema in the creation of aggregate or dispersed racial taxonomies, the standardization of

racial classifications, the conceptualization of racial categories as discrete or multiple, and the determination of which groups can access government

who gets a seat at the table within this policy universe, the relative power or influence

of its denizens and how they connect ideas about race to their preferred method of organization are at the crux of the production

of this racial project. The first section of this chapter establishes a conceptual framework that identifies important characteristics of

programming. Moreover,

policy networks and demonstrates their congruency with this dissertation’s overarching exploration of the schematic state. It details Marsh and Smith’s

macro-level

structures such as ideas and institutions shape the scope and power of policy networks;

2) processes of network policy formation institutionalize path-dependencies and access

points for network participants; and 3) network structure dovetails with network

interactions – that is, agent skills, bargaining and resources – and leads to the policy

outcomes of these cases.

(2000) dialectical approach to policy networks, which will be used in subsequent sections to examine the ways in which: 1)

Debates about identity, surveillance, and power must start with the

census—state classification renders subjects into objects of observation and

control

Mezey, 3 – Professor of Law at Georgetown University (Naomi, “Erasure and

Recognition: The Census, Race and the National Imagination”, 97 Nw. U. L. Rev. 17011768 (2003) Northwestern University Law Review, 2003)//jml

In modem America, the census epitomizes the examination as an in- strument of

power. In a sense the examination is for Foucault any ritualized form of documenting the

individual, and the census is a national rite of mass individual documentation. It is a

regularly administered, probing questionnaire, to which the state requires a response,

inquiring into myriad details of life which are at once mundane and intimate. 9 The

census makes each person

seen and known by an invisible bureaucracy; each person be- comes an object of

observation, a subject of surveillance.9 3 Where once the documentation of a life was saved for nobles

and heroes, in the modem age it has been democratized, and "it functions as a procedure of objectification

and subjection."94 And yet the census as examination also obscures the in- dividuality of

people by incorporating them into a bewildering mass of sta- tistics, into a comparative

system of collective facts that sets and adjusts our sense of the normal.95 It takes

individuals and turns them into "statistical people." 96 David Theo Goldberg has analyzed the

racial categories of the census from a Foucaultian perspective, focusing perceptively on the ways in which the literal bureaucratic

forms, used by the

Census Bureau and now count- less other agencies and organizations, reflect, reproduce, and

distribute ra- cial identity. 97 He locates the bureaucratic form as part and product of the epistemic shift that both

Foucault and Hacking detail, noting that statistics and forms emerge around the same time and as

part of the same process: forms give structure, order, and logic to data, allowing it to be

'formalized," to be turned into "information."9 The ordering of knowledge in this fashion is

intertwined with the creation and regulatory control of identity. "Formal identity is

identity conceived, manufactured, and fabricated in and through forms.... The form, and

the identity prompted and promoted by the form, is regulatory and regulative. The form

furnishes uniformity ... to identity, rendering it accordingly accessible to administration .... The form is the technology of scientific

management par excellence."9 9 Thus the

census and its attendant standardized forms can be seen as

a Foucaultian examination, a primary instrument by which the state exercises

disciplinary power on individuals. It is evident in the way it creates, counts, and arranges

objects; in its classifying and ordering of living beings; in its plotting of people into tables and forms in

order to best observe the most in- timate details of their lives: their living arrangements, the number of televi- sions and toilets in

their home, their commute times, their wealth, their skin color. This

power to make and arrange objects of

inquiry is particularly evident with respect to racial classification because race has

been one of the main axes of state disciplinary power in this country. This view of the

census, as examination and disciplinary instrument, is not limited to high theorists. In fact, currently this position is most ardently

espoused by some conservatives and civil libertarians, who argue that the census should be scaled back to fulfill only the minimum

requirement of "actual enumeration" set by the Constitution. In particular, these opponents of the census regard the questions about

income, race, and standards and style of living as overly intrusive, an invasion of privacy, and irrelevant to the Constitutional

purpose of the census.°° While civil libertarian concerns about the census are aimed primarily at the way the routine business of government regulation and redistribution invade citizens' privacy,'' they

also fo- cus on the issue of racial

documentation and surveillance. To substantiate their fears of government misuse of

census data, civil libertarians remind us that the federal government used racial

identifiers taken from census data to help round up Japanese Americans for internment

in camps during World War II,102 despite a strict policy of confidentiality. 13 Taken to its most ex- treme, the

disciplinary power exercised through the census does more than just see us, know us,

and tell us what is normal. It makes us who we are and situates us with respect

to others. It also makes evident that the power to dis- cipline and the power to

recognize are an indivisible power. As Foucault himself acknowledged, the disciplinary power that

operates through the documentation of the individual is not just repressive and

censoring, it is also, as I have argued above, creative and aspirational. "[I]t produces reality; it

produces domains of objects and rituals of truth. The individual and the knowledge that may be gained of

him belong to this production.""' 4

There’s no benefit to state programs based on race until the categories are

deconstructed—welfare programs solidify violent categories and

undermine struggles for justice

ESPINOZA 1997 (Leslie, Associate Professor of Law, Boston College Law School, California Law Review, October)

Race certainly is operational. 80 For each group, race provides benefits and burdens. As a hierarchical system, the benefits and

burdens are distributed in a grossly unequal and unjust way. Other

systems of oppression, such as misogyny,

homophobia and poverty, intersect with racism and synergistically operate to

disempower some and empower others. 81 Yet for all the complexity, we recognize race as a correlate, negative

and positive, to well-being. At the moment we recognize it, however, we also discount it - it could be capitalism, sexism, colonialism,

etc. The

complexity of oppression contributes to, and indeed may be at the heart of, our inability to

understand race. In the same way that we think we know who is white, who is black, who is brown, and who is [*1611]

yellow, we think that we know why she is poor, why she was fired, why she cannot read and why she is in jail. Naming and

understanding oppression seems like a catch-22. We use the master's tools to try to

dismantle the master's house and think we are making headway, only to discover that

the destruction of this house was part of a larger "urban renewal" plan to build a

"Master's Fortress." For example, as we break down racial categories, we find that each group

has a stake in maintaining their place in the racial order. Undocumented workers break

their back in the hot sun, but are grateful for work; women, in dilapidated housing and with

no hope for education or child care, raise small children and are thankful for a welfare check; sweatshop

slaves work interminable hours for a pittance but are relieved to pay off the cost of their

passage to America. And there are those who have moved up a step to own a small house in the

barrio or a vegetable cart in the market; or those whose third-cousin's daughter managed to finish technical school and who have

hope that one of their children will be in college instead of in a gang.

It is the focus on the crumb thrown their

way that keeps even the most oppressed from taking action for change. 82 There are

many examples of small benefit programs that are premised on definitional categories

for racially oppressed groups:bracero work permits, welfare benefits, refugee

immigration exceptions, targeted lending grants, minority business set-asides and affirmative action. The benefits

are always tenuous because the benefactor can alter the application and understanding

of the definitional category. This ambiguity is often used to pit different groups against

each other in a scramble for benefits. 83 It is also used to pit persons within categories

against each other. 84 [*1612] Tension and conflict within and between oppressed racial

groups keep us from forming coalitions. Yet, united action is the only hope for effectively

changing the vast disparities in wealth between social strata in this country. Racial outsiders

are stuck in the "bottom of the well" 85 if they buy into the myth that equality means

individual equality of opportunity. "Opportunity" has competition conceptually built into

it. Equality is viewed as the responsibility of the individual to take advantage of

opportunity. It is not understood as actual equality of basic material needs and it is not

understood as something derived from group action. Race definitions operate to define the "have-nots"

and to mask the correlation between race and the "haves." American social discourse attaches negative

characteristics by group; for example, he is poor because he is a lazy Spic. We do not attach success by racial group. Success is the

reward of individual characteristics, e.g., he is rich because he is smart, he works hard and he is ruthless. We

do not

acknowledge that, as a statistical reality, he is rich because he is a white male. Race

definitions go to the heart of our conception of equality. We learn that being racially

identified can hurt us: we are part of a group that is unfairly stereotyped and unfairly

treated. Likewise, we are taught that group identity does not lead to material success.

We "race" ourselves in a way that leaves us lonely, isolated and mired in poverty.

Our strategy is distinct from colorblindness and multiculturalism, both of

which have only served to circulate white supremacy—polyculturalism

allows us to build on the limited successes scored against white supremacy

to constitute more far-reaching resistance

Wendland 2003 (joe, peace activist in Michigan and Ohio and teaches in the Ethnic

Studies Department at Bowling green State University. Chopping Through the

Foundations of Racism With Vijay Prashad,

http://www.frictionmagazine.com/imprint/books/kung_fu.asp, LB)

Racism, like racialism, is not natural to human social relations. More specifically, Prashad shows with

devastating accuracy that, "White supremacy emerged in the throes of capitalism's planetary

birth to justify the expropriation of people off their land and the exploitation of people

for their labor." Although societies pre-dating capitalism and those outside of Europe did use slave

labor and were sometimes xenophobic and ethnocentric, Prashad argues that, "It would be inaccurate to reduce

this xenophobia or ethnocentrism to racism." Cultural and national differences

developed and recognized before the system of private expropriation of socially

produced value was transplanted by European (mostly English, Dutch, Portuguese and

Spanish) imperialism and were based primarily in language and geography -- not in

human bodies. Prashad concretely asserts historical and linguistic evidence that the primacy of color in the Indian caste

system emerged with the advent of British conquests. Another important aspect of this work is the discussion of fascism. Prashad

notes that, "Fascism

or a movement with fascistic tendencies has at its core hierarchy,

racism, and militarism." It tends to define the "nation" as "unitary" and tries to exclude or erase difference -- primarily

that of ethnicity or race. Such a movement tries every strategy or tactic to set aside the "mess of

democracy" and promotes the popularity of racial nationalism. Though readers likely will recognize

the US right-wing in this definition, Prashad also argues that elites in colonized (or formerly colonized)

countries are not immune to these tendencies. Especially within neocolonial frameworks

elites tend to try to emulate the sort of ideological and material practices of repression in

order to assert their own power over the colonized working class. The result is highly hierarchical

societies in which right-wing ruling cliques rely on imperialism (initially British, now American) to rule their countries. They

build their power on the ability to repress dissent and difference within their countries

and by orienting the labor and resources of their countries to imperialist interests. But,

even within this general picture of domination and fascism, the oppressed have historically fought back and, in so doing, built

unique and sometimes forgotten alliances. These

alliances, contrary to common misperceptions, have

a deep and powerful history among Asians and Africans. Prashad documents ancient links between

Africans and Chinese and Asian Indian merchant explorers. He notes Calcutta-born religious activist William Quinn, one of the

founders of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. He linksMarcus Garvey with Ho Chi Minh and Ghandi. Ho visited UNIA offices

while traveling in the US; Ghandi, while a leader of the anti-racist movement in South Africa, relied on Garveyite formulations and

followers to develop a message for his constituents in the Indian National Congress; and Ghandi influenced and was impressed by

the work of the leaders who formed the organizations that would become the African National Congress and the South African

Communist Party. By the mid-20th century, these tenuous relations had been transformed into full-fledged alliances among Third

World peoples. Rastafarianism

and its cultural expressions were likely as much the result of

the styles and habits of East Indian residents of Caribbean islands as they were of

African descended people. Racially oppressed Dalits in India emulated the organization and rhetoric of the Black

Panther Party, and representatives of the National Liberation Front (Vietnam) claimed to be "Yellow Panthers." Among Americans,

Asian American, Chicano, Black, Puerto Rican, and American Indian radicals borrowed from and left their marks on a broad

movement for social revolution. This

larger social trend was encapsulated, for Prashad, in the

martial arts films of Bruce Lee. This aspect of Prashad's work should open up doors for

greater detailed study of these movements. A powerful countervailing force to fascism -whether from the imperialists or from the compradors (intermediaries) -- in Prashad's

view, is an anti-racist and anti-imperialist national liberation movement formulated on

shared social position, customs and practices, rather than skin color or desire to

maintain class dominance. A true anti-imperialist strategy is a socialist-based movement. Prashad's description and

criticism of racism and its various disguises is crucial for contemporary cultural studies students and political activists. He

contrasts two forms of racism (white supremacy) -- colorblindness and liberal

multiculturalism. One of the successes of the civil rights movement, though it

did not end white supremacy, was to reform the terrain on which white

supremacists could operate. (Even Trent Lott and Phil Gramm -- one-time members of the White Citizen's

Council and KKK, respectively -- had to change the framework, or hide, how they moved within these circles in order to maintain

legitimacy.) Crude

blatant racist became sophisticated "colorblind" libertarians. They

appropriated and re-worded the rhetoric of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and demanded

the erasure of race. What they sought in reality was a political stick to use against the

mild gains of the civil rights movement -- affirmative action or other protections against

discrimination. Colorblindness was a way of normalizing the already normal white that dominates US society. To this

Prashad contrasts liberal multiculturalism. This version of white supremacy sets in

motion a variety of racialized and essentialized cultural positions, assumed to exist in

nature and to occupy the pre-designated skin tone and body shape of people, in order to

manage the complexity of a multicultural society. Diversity, rather than colorblindness,

is the political tool of social control and maintenance of class relations. When it comes down to it,

both of these ideologies translate race into a device for forcing working-class people to compete for vital but scarce resources falling

off the tables of capitalists. The

latter, however, as Prashad indicates, opens space within which

true anti-racist and anti-capitalist alliances can be organized and cultivated.

Identity categories are in constant flux—ontologizing race only reinscribes

violence

Hipwell, 4 - Department of Geography, College of Social Sciences, Kyungpook

National University (William T., ‘A Deleuzian critique of resource-use management

politics in Industria’ The Canadian Geographer 48, no 3 (2004) 356–377)//jml

Identity. When you begin making decisions and cutting it up, rules and names appear. And once rules and names appear, you should

know when to stop. (Tao Te Ching, quoted in Scott 1998, 262) The Deleuzian critique most important to this discussion is directed

against ontological ‘identity’— which Deleuze argues has underlain western thought since Plato. In simple terms, ontological

identity assumes that the ‘total field’ of reality can be reduced to discrete points or

‘identities’ that interact atomistically, much like balls on a billiard table. Deleuze shows that belief in

ontological identity is an error, since reality is a continuum (an unbounded ‘whole’),

not an aggregation of separate ‘points’. In this discussion, I use the word ‘identitarianism’ to

refer to the set of ideas arising from an ontology of identity. Identity is a useful fiction, employed to

make intellectual epistemologies of calculation and measurement possible. However, when its fictionality is forgotten,

identitarianism quickly contributes to serious social, political and ecological problems. A

list of identity categories familiar to readers would include human races, animal species and academic disciplines. Identities

are generalisations based upon some agreed-upon norm. Identitarianism

masks, misrepresents or excludes transitional or marginal cases that do not fit easily

into the identity category under consideration. Deleuze undertakes the most systematic and rigorous critique

of identity in Difference and Repetition (Deleuze 1994). His project is to show that the being supposed in an

ontology of identity is defined by what it is not; that it relies on a negative, external

support (the ‘is/is not’ duality, or Hegel’s thesis/antithesis’) and is thus ‘no being at all’ (Hardt 1993, 114). Ontological

identity denies the positive movement of being, or ‘becoming’, and thus creates a static,

negative and, ultimately, false picture of the world (Doel 1996, 430). In practice, the most

significant feature of identitarianism is the process of ‘striation’: Deleuze and Guattari’s term for the

mental or physical imposition of fixed, sedentary boundaries (enclosures) onto hitherto smooth space to create what philosopher

Paul Patton (2000, 112) has called a ‘homogeneous space of quantitative multiplicity’. Representational intellect In Deleuze’s view,

the myth of identity has had profound epistemological implications. This

is so because intellectual

epistemologies are necessitated by a belief in ontological identity. That is to say, identitarian

thinking holds that the only way of gaining reliable knowledge about the world, and to

make accurate predictions, is through conscious, intellect-based approaches, grounded in logic. This, Deleuze

suggests, is a mistake. Of course, if reality truly were made up of discrete identities, then measuring them and logically

calculating their interactions would surely be the soundest way of gaining access to knowledge about the real world. Deleuze does

recognise that logic and reason are very frequently successful strategies; he merely emphasises that they should not be granted

exclusive epistemological status. His argument is that reality is not, in fact, fundamentally atomistic and that therefore an

identitarian epistemology, how- ever useful, is ultimately inadequate. He shows that representation

is the inevitable

outcome of the privileging of intellect over intuition. Moreover, he argues that the fluid and

mobile nature of reality—which the intellect on its own can never adequately grasp—means that

representation is doomed to perpetual error. Arran Garrue (1995, 70) argues that representation

results from Platonic thought’s ‘celebration of eternal forms and its denigration of the changing, sensible world’ (on this point see

also Deleuze 1994, 59). In Deleuze’s view, the representational intellect cannot truly understand the continuity and flow that

characterise the world. Instead, we

see the world through our intellect as series of moments,

aggregations of units. Representation also leads directly to reductionism, where complex

ideas and conditions are simplified to the point of minimising, obscuring and distorting

them (Random House Webster 1998, 1618). John Ralston Saul (1993) has called this the ‘dictatorship of reason’. Deleuze would

almost certainly have agreed. Difference Chaos is not a stable condition or fixed state. It is a process, it is dynamic. It is more like the

changing relationship between things than the things them- selves. (Merry 1995, 11) For Deleuze, static

identities are

dangerous illusions: the real world is, by contrast, always fluid and mobile; reality is

ontologically characterised by ‘difference’. This difference is not, as it might seem, difference between things (an

identitarian notion) but rather the idea that reality is a continuum of interplay, interpenetration and interconnectedness and that

‘things’ are merely intensities in this continuum, internally constituted by the interplay of different forces, and themselves

interacting and interpenetrating with everything around them. In this sense, allegedly

separate entities are

mutually constitutive and interdependent, and treating them as entirely separate

inevitably does intellectual and physical violence to the world. In an ontology

of difference, the world is viewed holistically. Differential being is defined on the basis of

what it is rather than what it is not. It is dynamic, not static. As Deleuze (1988, 123) puts it, ‘the

important thing is to understand life, each living individuality, not as a form, or a

development of form, but as a complex relation between different velocities’. While we may,

for practical purposes, speak of ‘a tree’, ‘a fish’, ‘the human species’, etc., awareness of ontological difference reminds us that it is a

mistake to abstract such things from their dynamic and continuous context. Prior to striation by identitarian forces, the world is

made of ‘smooth space’ (Deleuze and Guattari 1987, 474–500), or what Patton (2000, 112) has called ‘the heterogeneous space of

qualitative multiplicity’. In smooth space, diverse and unexpected interconnections may appear and reconfigure (‘lines of flight’).

Smooth space is continually in flux; it is difficult to know intellectually and (therefore) difficult to control. To know

one’s way in the tangle of primeval forest or other ‘wild zones’ (Dalby 2001), one must have good instincts.

Words matter—our exposure of racial tradeoffs can help to disrupt white

supremacy. The state is important but words on the census are proof that

the circulation of categories in language also forms the social world in

which we live

HARRIS 1994 (Angela, Professor of Law, University of California, Berkeley, Boalt Hall School of Law, California Law

Review, July)

Discourse theory relies on a social constructionist understanding of the concepts "language" and "power." 151 The central insight of

discourse theory with respect to language is the blurring of the line between the "real" and the "ideal." 152 Discourse

theory

puts language at the center of human experience by asserting that language not only

describes the world, it makes it. 153 We only make sense of experience through the

conceptual categories [*773] we use to interpret and classify it. Even sensory perception itself, which we

tend to think of as an unmediated encounter with pure "reality," is better described as a process of interpretation in which our brains

pick and choose the stimuli to which to pay attention on the basis of preestablished conceptual frameworks. 154 This view of

language suggests

an important role for "power" in creating and maintaining the world. 155

As theorists have recognized, one of the most potent kinds of power one can have is the power to

label experience. 156 The struggle over what to call things, and hence how to understand

and ultimately experience them, is a struggle over social power. Just as history is written

by the winners, language is shaped by the socially dominant. 157 In post-structuralist theory, however,

"power" is not only negative or repressive - an infringement on prior liberty - but also productive and creative. If "power" is

understood simply as the human interactions that stabilize social meanings and practices, then the concept includes the power to do

something as well as power over someone. 158 In this broad account of "power," there is no individual or social group completely

lacking in power. 159 Power

circulates, in Foucault's terms, from the bottom up, not [*774] just from the

top down; resistance is always possible even when power is at its most repressive. 160 In

discourse theory, then, language is implemented through power relations which, in turn, are

shaped by social understandings created through language. A "discourse" refers both to a system of

concepts - the set of all things we can say about a particular subject - and to the relations of power that maintain that subject's

existence. The

project of post-structuralist theory is to tell stories about how certain

discourses emerge, shift, and submerge again. Under a post-structuralist account, then,

"race" is neither a natural fact simply there in "reality," nor a wrong idea, eradicable by

an act of will. "Race" is real, and pervasive: our very perceptions of the world, some theorists

argue, are filtered through a screen of "race." 161 And because the meaning of "race" is

neither unitary nor fixed, while some groups use notions of "race" to further the

subordination of people of color, other groups use "race" as a tool of resistance. 162 The

task of a discourse theory of race would be to chart this history. In Omi and Winant's phrase, "race"

is "an unstable and "decentered' complex of social meanings constantly being transformed by political struggle": 163 the concept

with which, John Calmore says, CRT begins. 164

Case

Advantage

Impacts

*The census creates a perception of the world that brackets off individuals

into neat identity classifications

Kertzer and Arel, 2 - * PhD, Paul Dupee, Jr. University Professor of Social Science,

Professor of Anthropology, and Professor of Italian Studies at Brown University **PhD,

Associate Professor of Political Science and Chair of Ukrainian Studies at the University

of Ottawa, Canada (David and Dominique, “Census and Identity: The Politics of Race,

Ethnicity, and Language in National Censuses,” 2002)//jml

In short, the use of identity categories in censuses – as in other mecha- nisms of state administration –

creates a particular vision of social reality. All people are assigned to a single category,

and hence are conceptualized as sharing, with a certain number of others, a common collective

identity. This, in turn, encourages people to view the world as composed of distinct groups

of people and may focus attention on whatever criteria are utilized to distinguish among

these categories (Urla 1993). Rather than view so- cial links as complex and social groupings situational, the view

promoted by the census is one in which populations are divided into neat

categories. Appadurai’s (1993: 334) comment is apropos here: “statistics are to bod- ies and social types

what maps are to territories: they flatten and enclose.” In Europe, national statistics-gathering was

developing in the nine- teenth century as a major means of modernizing the state. International congresses were held where the

latest statistical and census developments were hawked to government representatives from across the continent. Knowledge was

power, and the knowledge of the population produced by the census gave those in power insight into social conditions, allowing

them to know the population and devise appropriate plans for dealing with them. As Urla (1993: 819) put it, “With the

professionalization and regularization of statistics-gathering in the nineteenth century, social statistics, once primarily an

instrument of the state, became a uniquely privileged way of ‘knowing’ the social body and a central technology in diagnosing its ills

and managing its welfare.” Such

language, not coincidentally, brings to mind Foucault, and his

view of the emergence of a modern state that progressively manages its population by

extending greater surveillance over it. In examining state action in the construction of collective identities, we

enter into the com- plex debates over what is meant by “the state.” The state itself is, of course, an abstraction,

not something one can touch. Such a perspective impels us to examine the multiplicity

of actors who together represent state power, and discourages us from the view that “the

state” necessarily acts with a single motive or a single design. An inquiry into censuses

and identity for- mation, then, requires examination of just which individuals and

groups representing state power are involved, and how they interrelate with one another as well as with the

general population. Pioneering research of this sort has been done on the impact of various advocacy groups. Espe- cially valuable

work has been done on the Census Advisory Committee on Spanish Origin Population in formulating the “Hispanic” category in the

1980 US census (Choldin 1986). Similarly important work has been done on the role of ethnographers, geographers, and party

activists in devising an official list of ethnic “nationalities” for the first Soviet census of 1926 (Hirsch 1997). Sorely needed are more

ethnographic efforts at examining the workings of state agencies of various kinds – from legis- latures to census-takers – in their

interactions with each other and with the people under their surveillance.3 That

the kind of counting and

categorizing that goes on in censuses is an imposition of central state authorities, and

thereby a means of extending central control, has long been recognized. Indeed, ever since the

first census-takers ventured into the field, struggles between local people and state authorities over

attempts to collect such information were common. Such was the case in mid-eighteenth-century France,

when various at- tempts to collect population data by the central government had to be abandoned. Opposition came not only from a

suspicious populace but also from local governments. Each feared that the information was be- ing gathered to facilitate new state

taxes (Starr 1987: 12–13). These first population enumerations were typically identified with attempts to tax (often newly acquired)

populations, as well as to conscript them for labor or military service.

The census is a form of racial ordering that creates processes of

assimilation into the categories of whiteness

Mezey, 3 – Professor of Law at Georgetown University (Naomi, “Erasure and

Recognition: The Census, Race and the National Imagination”, 97 Nw. U. L. Rev. 17011768 (2003) Northwestern University Law Review, 2003)//jml

But protecting traditional race categories and race-based rights and at the same time allowing for a

radical rethinking of identity does not come without costs. One cost may be the very thing the

traditional civil rights groups feared most from a single multiracial category: movement

of more minorities away from a single racial identity and potentially toward white- ness.

Of course this is not just the result of individual choice, but occurs through the reclassification of bodies based on changes to the

categories. In discussing the oft-cited projections that the United States will be a minority- majority country by 2060 based on

current immigration trends, john powell notes that he is skeptical "that we will categorize those immigrants such that the majority is

non-white. When

we talk about changing demographics we must remember that we are in

control of how we categorize our popula-tion. Racial ordering is not a natural

phenomenon." If history is any in- dication, enough people will be allowed to claim whiteness that

the country can maintain a white majority, with its attendant white power and privilege, and the nation as

currently imagined can be preserved. There is already a good deal of flexibility in the white category even as it is currently defined, as

a person "having origins in any of the original peoples of Europe, the Middle East, or North Africa," '64 and there

is reason

to expect this definition will continue to change with time. Even if it does not, racial

performance will undoubtedly continue to inform our legal definitions.365 Immigrants, much

like they did one hundred years ago, are changing the meaning of whiteness. There were 28 million foreign-born residents of the

U.S. in 2000; two-thirds reported that they were white. 66 Not

only are American race categories somewhat

meaningless to many immigrants, but to the ex- tent they have meaning it is abundantly

clear that immigrants "equate 3'67 whiteness with opportunity and inclusion." Furthermore, the

His- panic/Latino category, an already ambiguous ethnicity, is another possible gateway to whiteness. In 2000, nearly half of all

Hispanics classified them- selves as white. 68 But of course, the OMB did not undo the basic race categories nor did it create a

separate multiracial category. Hence, another

important cost in its final decision is to those who

understand themselves as multiracial and who feel that they exist in liminal spaces on

official forms, in the national imagination, and in communities and even families. This

nonrecognition is acknowledged and perhaps exacerbated by the Census

Bureau when it re- 3'69 fers to multiracial people as "The Two or More Races

Population." By not fundamentally changing the categories by which we understand and

struggle with race, the check-all-that-apply decision continues to discipline and discount those who do not fit within them.

This statitization of racial identity furthers state control and reinforces

racial domination

Nobles, 2 - Arthur and Ruth Sloan Professor of Political Science at MIT (Melissa,

“Census and Identity: The Politics of Race, Ethnicity, and Language in National

Censuses,” “Racial categorization and censuses” 2002)//jml

Race as discourse To count by race presumes, of course, that there is something to be counted.

Intellectuals, political elites, scientists, and ordinary citizens have considered race an

elemental component of human identity, of what it means to be human. The weight of scientific thought about

race can hardly be overestimated, especially in census-taking. As the historian Nancy Stepan observes, the modern period of 1800 to

1960 was one in which European and American scientists were “preoccupied by race” (Stepan 1982: x). There

have been,

and still are, popular understandings of race and of proper racial identifications. These

popular understandings are sometimes directly at odds with elite and scientific understandings. They are, as often, informed by

them, with variation. Given

then that race was (and continues to be) thought elemental to

human identity, it would seem no surprise that the census counts by race. The connection

between race and census-taking would seemingly end there. Every human body has a racial identity, and population censuses count

bodies, so racial data are obtained through the counting of bodies. But

if we question the supposed rigid

quality of race and explore its evident plastic qualities, the way is opened to better

explaining what race is and to understanding the role of the census in

creating it. The scholarship that refers to race in one way or another is vast and

continues to grow. However that portion of it that examines the concept of race itself is less voluminous, though still

substantial. An intellectual consensus exists today whereby most agree that racial categories

have no biological basis. This is true even as persons still commonly refer to individuals and groups on the basis of

similar and dissimilar physical characteristics, and use the term 'race' and its accompanying discourse, however incoherent, to

substantiate these distinctions. With

racial categories believed to have no biological basis, the task

for scholars has shifted to defining, explaining, describing, and analyzing race. The resulting

theories vary as widely as the disciplines. According to the sociologists Michael Omi and Howard Winant, race is “a concept

which signifies and symbolizes social conflicts and interests referring to different types

of human bodies” (1994: 55). The historian Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham understands race to have various faces: race, then,

is a “social construction”; “a highly contested representation of relations of power between

social categories by which individuals are identified and identify themselves”; “a myth”;

“a global sign”; and a “metalanguage” (1992: 251–74). The philosopher David Theo Goldberg argues that race is an

“irreducibly political category, ” in that “racial creation and management acquire import in framing and giving specificity to the body

politic” (1992: 563). The American Anthropological Association today views race as a concept with little scientific validity, burdened

by its association with racist practices, and less useful than ethnicity in capturing the “human variability” of the American people.

According to the legal scholar Ian Haney-Lopez, the

law constructs race legally by fixing the

boundaries of races, by defining the content of racial identities, and by specifying their relative disadvantage and

privilege in American society (1996: 10). Literary critic Henry Louis Gates sees race as the “ultimate trope of difference because it is

so very arbitrary in its application” (1986: 5). Historians

of ideas have traced the development of racial

thought in various countries and different historical epochs (Jordan 1968; Horsman 1981; Gould 1981;

Barkan 1992; Skidmore 1993). Political scientists view race as a tool, used both by white

elites, to insure white domination, and by blacks and other nonwhites, as a

potential weapon to resist such domination by blacks and other nonwhites (Hanchard 1994;

Marx 1998). We are a long way, indeed, from seeing race as fixed, objective, and in significant ways, deriving its existence from

human bodies at all. Race stems from and rests in language, in social practices, in legal definitions, in ideas, in structural

arrangements, and in political contests over power. This chapter builds on certain trends of this theoretical work. It treats race as a

discourse, meaning that race

is a set of shifting claims that describe and explain what race is and

what it means. Although this discourse has various sources in religion, law, and science, it is the latter – science – that has

been the most influential in census-taking in the United States and Brazil. Indeed, the influence of scientific thinking argues against

viewing racial discourse as merely a tool to be manipulated by elites or masses. While it is true that political and intellectual elites

were largely responsible for creating and promulgating scientific racial thought, they did so not only to manipulate and control;

rather, they thought that they were adhering to nature's laws of human diversity. However, because

scientific

investigation results from human endeavor, it is inevitably shaped by larger political,

social, and cultural processes. Racial discourse, then, does not exist without its various

agents or its institutional channels. Scholars are right in stressing race's discursive nature. Yet their theoretical

formulations run the risk of obscuring the institutional sites of its construction, maintenance, and perpetuation. Census

Bureaus are such sites because they help to create, maintain, and advance

racial discourse. As we will see, in both countries racial discourse and racial categorization on censuses have

focused on the ideas of “whiteness, ” “blackness, ” and “mulattoness. ” However, racial

discourse has been applied to other groups as well. In the United States, elite concerns

about other “nonwhite” people – the Chinese, Japanese, and especially Native

Americans – were also reflected and advanced by the census, although to a far lesser degree.

Twentieth-century Brazilian censuses did not enumerate indigenous persons separately (with an indigenous category) until the 1991

census. Racial

discourse supplies the boundaries of racial memberships and their content,

and is itself context specific. It therefore varies from one national setting to the next. In nineteenth-century colonial

Malaysia, for example, race pertained to the broad grouping of Europeans, Malays, Chinese, Indians, and others (Hirschman 1986),

and by 1901 censuses counted them as “races” (Hirschman 1987). In Guatemala, Ladinos and Mayas are the two major racial groups.

Twentieth-century Guatemalan censuses have supposedly charted the decrease in Mayas, thereby making Guatemala a “whiter, less

Indian” nation, according to its political elites (Lovell, Lutz 1994: 137). Likewise,

the relation of such discourse

to census-taking may vary in its particularities, but the general pattern holds: censustaking reflects, upholds, and often furthers racial discourse.

Slavery impact

Wander et al. 93 (Philip Wander has specialized in slavery, Native American, and

foreign policy rhetoric. He has a Ph.D from University of Pittsburgh and is a presidential

professor at Loyola, 1993. http://www.geraldbivens.com/rd/wander-roots-of-racialclassification.pdf) JG

At first there were white and black slaves who suffered alike from the overwhelming English and European passion for material and

the move from racial classification to

racialization—as slave and black become synonymous. According to some scholars, this move was

due to two unique characteristics of the American colonial experience. The first was the prevailing attitude toward

property. For centuries, Europeans held a firm belief that the best in life was the expansion of

self through property and property began and ended with possession of one’s body (Kovel, 1984, p. 18). However, this law

was violated by New World slavery, and it differed in this way from other slave systems. The slave owners, in

proclaiming ownership of the bodies of the slaves, detached the body from the self and then

reduced his self to sub-human status (justified by the racial categorization system). Slave

spiritual expansion. A closer look at U.S. colonial history reveals

property became totally identified with people who happened to have black skin, the color that had always horrified the West (Kovel,

1984, p.21)

Slavery impact #2

Wander et al 93 (Philip Wander has specialized in slavery, Native American, and

foreign policy rhetoric. He has a Ph.D from University of Pittsburgh and is a presidential

professor at Loyola, 1993. http://www.geraldbivens.com/rd/wander-roots-of-racialclassification.pdf) JG

The roots of racial classification emerge from the naturalistic science of the 18th and 19th century. During this time, scientific

studies extended the classifications of humankind developed by zoologists and physical

anthropologists by systematically measuring and describing differences in hair texture. skin

color, average height, and cranial capacity in various races. These studies reflected a naturalist

tradition—an assumption that the physical world had an intrinsically hierarchical order

in which whites were the last and most developed link in "the great chain of being. (Webster,

1992. p. 4.)… How were these categories used socially and politically? To answer these questions. we must examine the historical

contexts in which this scholarship occurred This

scholarship occurred during a period of global

expansion by European powers and of westward expansion in the United States. The research on

racial categories supported these efforts--often aimed at subjugating nonwhite peoples

(Fusser Rosenberg, 1999: Omi & Winant, 1994). Anthropologists and Egyptologists found evidence of

cultural, social, technological, and spiritual inferiority of nonwhite races throughout human history.

These conclusions were corroborated by colonial officials and newspaper reports that described and discussed the inferiority of nonwhites in colonies and potential colonies throughout the world. By

using the research findings described above,

race theory helped to explain and justify the expansion and colonizing by white peoples,

their subjugation of nonwhite peoples in Africa, Asia. and the Orient, and the continuing

domination of nonwhite peoples—slaves, peasants, aborigines, and the poor at home.

Racism turns nuke war

Racism make nuclear war inevitable

KOVEL 1988 (Joel, Distinguished Professor of Social Studies at Bard University, White Racism: A Psychohistory, 1988, p. xxix-xxx)

As people become dehumanized, the states become more powerful and warlike. Metaracism signifies the

triumph of technical reasoning in the racial sphere. The same technocracy applies to militarization in general, where it has led to the inexorable drive

There is an indubitable although largely

link between the inner dynamic of a society, including its racism, and the external

projection of social violence. Both involve actions taken toward an Other, a term we may define as

the negation of the socially affirmed self. Communist, black, Jew—all have been Other to the white West. The Jew has, for a while at

least, stepped outside of the role thanks to the integration of Israel within the nations of the West, leaving the black

and the Communist to suffer the respective technocratic violences of metaracism and thermonuclear deterrence. Since the initial writing of

toward thermonuclear weaponry and the transformation of the state into the nuclear state.

obscure,