AP Language and Composition The Cumulative Sentence Sentence

advertisement

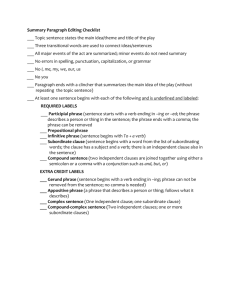

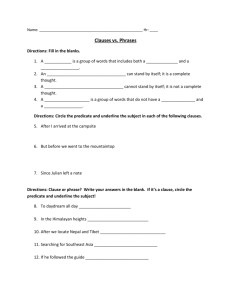

AP Language and Composition The Cumulative Sentence Sentence variety, particularly a mix of short and long sentences, is easy on the reader’s eyes, ears, and mind. One kind of long sentence is the cumulative sentence, which consists of an independent clause and one or more modifying phrases. The cumulative sentence’s modifying phrases circle back to explain or to describe. Consider these cumulative sentences from the point in Robert Penn Warren’s short story “A Christmas Gift” when the poor farmer’s son first visits the doctor’s living room: The boy looked at all the objects in the room, covertly spying on them as though they had a life of their own. The fire spat and sputtered in mild sibilance, eating at the chunks of sawn wood on the hearth. Against the plump little cushion, its color so bright, the hat was big and dirty. As you can see from Warren’s sentences, the cumulative sentence lingers in the moment, whether that moment is one of quiet observation or intense excitement. It’s ideal for the narrative and descriptive modes of rhetoric. (Can you spot the independent clause in each of Warren’s three sentences? I’ve put each one in bold font.) I. How to Accumulate a Cumulative Sentence All sentence types have a little grammar you have to master. As a practitioner of the cumulative sentence, you’ll become great at recognizing phrases and independent clauses. You’ll also get good at writing phrases that leave no doubt as to whom or what they are modifying. To build a cumulative sentence, (1) start with an independent clause, like this one: The fire finally reached the hunters’ cabin. (A clause, you recall, is a group of associated words that includes a subject and a verb. In the clause I’m using above, fire is the subject and reached is the verb. An independent clause is a clause that can exist on its own as a sentence.) Then (2) add one or more modifying phrases. (A phrase is a group of words that can’t exist as a sentence but acts like a single part of speech. A modifying phrase, for instance, acts like an adjective or an adverb – like a modifier, in other words.) Here is my modifying phrase (acting like an adjective): roaring like ocean waves breaking on the shore Finally, (3) arrange the sentence for clarity and good effect. (In other words, work on your syntax – your sentence structure.) Unlike adjectives and adverbs, modifying phrases are free modifiers. That means you have lots of choices about where you put phrases in a sentence. I’ll combine my phrase and clause three ways and then comment on each combination: AP Language and Composition AP Language and Composition Kind of Branch (where the phrase comes off the “trunk” – the main clause) Arrangement Comment Left branch Roaring like ocean waves breaking on the shore, the fire finally reached the hunters’ cabin. This works. It might add mystery since the reader doesn’t know what is “roaring” and what “it” is, but it also risks confusion for the same reason. Mid branch The fire, roaring like ocean waves breaking on the shore, finally reached the hunters’ cabin. This might be the best syntax of the three. It can be confusing to our readers sometimes when we keep the main clause’s subject and verb, but it works fine here. Right branch The fire finally reached the hunters’ cabin, roaring like ocean waves breaking on the shore. Bad. The syntax suggests that the cabin is roaring instead of the fire. The phrase is a misplaced modifier here. Try the three steps here on a sentence of your own invention: (1) Start with an independent clause: (2) Add one or more modifying phrases: (3) Arrange the sentence for clarity and good effect: AP Language and Composition II. Two Very Special Phrases You can use a variety of phrases in a cumulative sentence, two of which have special names we’ll learn: the participial phrase and the absolute phrase. A. The Participial Phrase One of the most powerful and common phrases is the participial phrase, which (of course) is a phrase that begins with a participle: Buried in the sand for centuries, the wooden ship felt like driftwood beneath the vacationers’ feet. Lurking just beneath the hot sand, the wooden ship felt like driftwood beneath the vacationers’ feet. A participial phrase sounds like a complicated idea, but it’s not. A participial phrase starts with a participle. Participles are easy to spot: they end in –ed or –ing. So they look like verbs, but they act like adjectives. (The two participial phrases above – buried and lurking – act like adjectives modifying ship.) There are two kinds of participles. Past participles end in –ed (buried, for example), and present participles end in –ing (lurking, for example). Try writing your own cumulative sentence with a participial phrase: (1) Start with an independent clause: (2) Add a participial phrase (your choice of a past or present participle): (3) Arrange the sentence for clarity and good effect: B. The Absolute Phrase Here’s an absolute phrase in bold: The bleachers rocking with towel-waiving students, our opponents sometimes felt as if they were playing on the deck of a storm-tossed ship. The “absolute” in “absolute phrase” means that it can almost exist on its own in content and structure. With regard to content, an absolute phrase doesn’t really modify anything specific in the base clause. (That means it’s hard for it to be misplaced the way other modifying phrases can be! (see page 60 above.)) But the absolute phrase gives the reader lots of extra information. With regard to structure, an absolute phrase is almost a sentence. It usually amounts to a noun (bleachers) followed by a participial phrase (rocking with towel-waiving students). But even though it has a noun (bleachers) and a participle (rocking), it’s not quite an independent clause. (The bleachers were rocking with towel-waiving students, by contrast, is an independent clause.) AP Language and Composition You can make a cumulative sentence with an absolute phrase using the three-step process I set out above. Or, if you’d prefer, you can do it this way: (1) Write two sentences. The track team was running up and down the halls. We couldn’t hear half the things our club sponsor was trying to say to us. (2) Combine them into one sentence by changing the verb in one sentence to a verbal (a verb-looking thing that doesn’t function as a verb). In other words, pull out the auxiliary verb. That sentence will become a phrase. The track team running up and down the halls, we couldn’t hear half the things our club sponsor was trying to say to us. Try writing your own cumulative sentence with an absolute phrase: (1) Write two sentences. (2) Combine them into one sentence by changing the verb in one sentence to a verbal (a verb-looking thing that doesn’t function as a verb). That sentence will become a phrase. III. A Menu of Phrases Here are the most common phrases used to make a cumulative sentence: Phrase (& other material) Example Use a participial phrase. Licking his bowl clean, the cat began to purr. Use an absolute phrase. The cat licking his bowl clean, everyone in the house was finally finishing dinner. Pick a noun out of the clause and start a phrase. The scout tended his fire, a fire fueled by branches from the scoutmaster’s prized apple tree and lit with torn-out pages from his Boy Scout Manual. Use a noun and a prepositional phrase. The child stuffed the cookies in her pocket, a sly grin on her face. Use an appositive (a noun or phrase that identifies or explains a noun beside it). A landlocked state, North Dakota nevertheless has many lakes. Use a possessive pronoun Its bowl emptied of the thickest cream the cow English, a language with Latin, Germanic, and Norman roots, is difficult to learn. AP Language and Composition and any kind of phrase. could produce, the cat began to purr. [An absolute phrase] Use a simile or metaphor in a phrase. The woman slowly opened the chest like Pandora with a second chance. [Two prepositional phrases] Now try your hand at some longer cumulative sentences by ordering several phrases off of the above menu: (1) Real tears ran down the clown’s face, his _________________________________________________ , his _________________________________________________ , the crowd ____________________________________________ . Checklist: are all three of your phrases really phrases? In other words, your phrases aren’t clauses, are they? (Clauses have subjects and verbs; phrases don’t.) (2) Susan and her mother sat down at the restaurant’s best booth, looking _______________________________________________ , ordering _______________________________________________ , the booth ______________________________________________ . IV. Circling Back and Digging Deeper Every phrase in a cumulative sentence can modify the independent clause or something in that clause. The phrases circle back to a clause like birds that fly from a tree and then back to it. The phrases are all on the same syntactical level since they modify the same clause. For instance: Red-faced and smiling, Maria sat on the soft, blue mat, (1) her hand uncertainly running through her disheveled hair and rubbing the back of her neck, (2) her eyes lowered to avoid the stares of her former classmates, (3) most of her new school’s stadium applauding madly at her for breaking the district pole vaulting record. Now you try it: ____________________________________ ,[independent clause] (1) _____________________________________________ , [phrase modifying the clause or something in it] (2) ______________________________________________ , [phrase modifying the clause or something in it] (3) ______________________________________________ . [phrase modifying the clause or something in it] AP Language and Composition Instead of circling back, a cumulative sentence may dig deeper. After the first phrase, each phrase can modify a previous phrase instead of the clause. Here’s an example: The family spent their last twenty dollars on pizza, [independent clause] (1) a food that brought back memories of better times, (2) pleasant years when the parents would order out twice a week from nearly any restaurant in Calicoville, (3) a company town once flush with mining money but now boarded up after the second Calico mine collapsed the year before, (4) the dark year that had also seen the deaths of three of the town’s men from mining accidents and of two others, including the family’s father, from Black Lung Disease. Notice that, in the above sentence, each of the phrases after the first one modifies something in the phrase preceding it. But notice also the effect of such a sentence. It may reveal a narrator whose every thought leads almost compulsively to recent tragedy. It also thickens plot and mystery even as it reveals more detail. Now you try it: The astronomer stared through the telescope at his newly discovered galaxy, [independent clause] (1) ______________________________________________ [phrase modifying clause] (2) _______________________________________ [phrase modifying previous phrase] (3) ________________________________ [phrase modifying previous phrase] Of course, most longer cumulative sentences don’t just circle back or don’t just dig deeper. Most circle back and dig deeper. Here’s an example: The girl stood alone at the bus stop for over an hour, (1) her uncle having seen her out the door ten minutes after the bus had left, (2) his wristwatch having silently stopped at breakfast that morning, (3) her hands and toes becoming numb in the thin, bright January air. Conclusion Now that you’ve studied cumulative sentences, you’ll spot your favorite writers employing them. I think you’ll find also that cumulative sentences will improve how much information, variety, tone, and drama you can pack into your own sentences. Enjoy!