Edits to make for entire Research Project

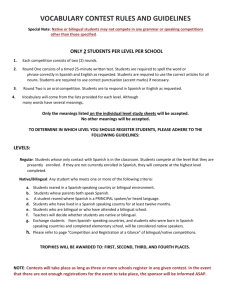

advertisement

Running head: EFFECT OF SPANISH ENGLISH CLUSTER REDUCTION EFFECT OF SPANISH ON ENGLISH CLUSTER REDUCTION IN SPANISH-ENGLISH BILINGUAL CHILDREN A Research Proposal Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science In The Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders by Melissa L. Gutierrez, B.A. Caroline H. Johnson, B.A. Haley E. Schmitt, B.A. Lori N. Tyler, B.A., M.A. Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center Communication Disorders Department 1900 Gravier St., New Orleans, LA 70112 1 EFFECT OF SPANISH ON ENGLISH CLUSTER REDUCTION 2 Abstract Between 1980 and 2010, there has been an influx of Hispanics in the population of the Greater New Orleans metropolitan area of Louisiana (U.S. Department of Commerce, United States Census Bureau, 2013). As a result, more children of Hispanic descent are learning English at school. According to the National Clearinghouse for English Language Acquisition (2011), “Spanish-speakers constitute more than 80% of [English Learner] students.” Due to the large number of Spanish-English bilingual speakers in the population, more research is needed to aid speech-language pathologists in treating speech-language disorders. Although there have been some studies evaluating the language development of bilingual Spanish-English children, most focus on syntactic or lexical development. However, there are few studies on the phonological process of cluster reduction in bilinguals (Goldstein, 2004). The purpose of this study is to analyze cluster reduction in Spanish-English bilinguals. Researchers expect to find that the lack of clusters in Spanish will increase cluster reduction in English in bilingual children. Using a mixedmethods quasi-experimental and qualitative design, researchers will assess the language skills of twenty typically developing second grade students in both English and Spanish by administering the Contextual Probes of Articulation Competence Spanish (CPAC-S), Secord Contextual Articulation Test (S-CAT), and parental questionnaires. Researchers will collect data through assessment and language samples for five categories (word initial, word final, word medial, sentence level, and spontaneous speech). The results of the assessments will be displayed in a graph to identify trends in data collection. EFFECT OF SPANISH ON ENGLISH CLUSTER REDUCTION 3 Table of Contents Title Page……………………………………………………………………………...…………….i Abstract ……………………..……………………………………………………………….….…ii Biographical Sketches…………………………………..…...……….…………………………….4 Research Protocol……………………………………………………………………..………..…..6 Background and Significance………….………….……………………………....……….6 Specific Aim ……………………………...…..……………………………………….......9 Methods...………… …………..………………………………….……………...……….11 Participants ………...…………………………..…………………………….…...11 Procedures..………………...……………………………………………..………12 Data Analysis……………………………………………………………………..14 Instruments …………………..………………………………….……………..…15 Reliability and Validity ………………………………………………………..…16 References…………………………………………………………..…………....…………….…18 EFFECT OF SPANISH ON ENGLISH CLUSTER REDUCTION 4 Biographical Sketches Melissa Lorena Gutierrez is a Speech-Language Pathology Masters student at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center in New Orleans, Louisiana. She received a Bachelor of Arts from Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge in December 2012. In the fall of 2012, she assisted Dr. Janet Norris with a language study at a local elementary school. She is a member of the National Society of Leadership and Success and the National Student Speech-Language Hearing Association. Melissa is a bilingual Spanish-English speaker with interest in bilingual speech therapy. Caroline Haddox Johnson earned a Bachelor of Arts in Linguistics and French at Tulane University. She worked as an assistant teacher at a French immersion school in New Orleans and as a teacher at French immersion camps. After obtaining a TESOL (Teaching English as a Second Language) certificate from Oxford Seminars, she taught English as a Second Language (ESL) to Hispanic adults in New Orleans, to Russian children and adults in Russia, and then returned to the United States. to pursue a degree in Speech-Language Pathology. She is currently a graduate student at Louisiana State University-Health Sciences Center pursuing a Masters in Communication Disorders with an emphasis in Speech-Language Pathology. Haley Elizabeth Schmitt obtained a Bachelor of Arts from Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge in May 2012. Haley was a member of Chi Omega and Rho Lambda Leadership Society. She is working with school-age children on various subjects including Spanish and English in the Greater New Orleans metropolitan area. She is an active member of National Student Speech Language Hearing Association. She is currently attending Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center in New Orleans, Louisiana where she is studying to become a certified speech-language pathologist. EFFECT OF SPANISH ON ENGLISH CLUSTER REDUCTION 5 Lori N. Tyler is currently a graduate student at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center in New Orleans, Louisiana where she is pursuing a Masters in Communication Disorders in Speech Language Pathology. She received a Masters of Arts in Spanish Philology from St. Louis University, and a Bachelor of Arts degree in Spanish from Loyola University New Orleans. She is a former teacher who has worked with the Hispanic community in the Greater New Orleans area for six years in translation and interpretation, research assistance, social justice, and journalism. EFFECT OF SPANISH ON ENGLISH CLUSTER REDUCTION 6 Background and Significance Over the past thirty years, America’s language diversity has changed drastically (U.S. Department of Commerce, United States Census Bureau, 2013). The population of people five years and older speaking a language other than English has increased from 26,785 to 126,136 between 1980 and 2010, a change of 40%. The number of Spanish-speakers increased 60% from 1980 to 2010 respectively from 19,135 to 84,138. The prevalence of bilingual homes in the United States as of 2010 is 13.5 million (U.S. Department of Commerce, United States Census Bureau, 2013). “The use of a language other than English used at home increased by 148% between 1980 and 2009 and this increase was not evenly distributed among languages” (Ortman & Shin, 2011, p. 1). Given the results presented by Ortman and Shin (2011), the growth of multiple languages being spoken in the United States has caused an increase in the number of bilinguals. According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, bilingualism is defined as “the ability to speak two different languages” (Dictionary and Thesaurus-Merriam-Webster, 2013). However, one must consider the amount of exposure and age of acquisition of each language (Barlow & Enriquez, 2007). The term bilingualism is ambiguous as there is no consensus on its definition amongst well-known researchers. For the purposes of this study, researchers define bilingualism as proficiency in two languages. Even though there is a great increase in bilinguals in the United States, there is not much research about bilingual language development. Most of the research on bilingual children focuses on syntactic or lexical development; however, there is a dearth of information about the phonological development and disorders of bilingual children (Goldstein, 2004). According to current research (Barlow & Enriquez, 2007; Goldstein & Gildersleeve-Neumann, 2007), there are EFFECT OF SPANISH ON ENGLISH CLUSTER REDUCTION 7 three models of phonological development in children who are bilingual. The Unitary Systems Model (USM) states that children have one phonological system for both languages. With increasing use of each language, bilingual children gradually separate their systems into two distinct languages around age two (Barlow & Enriquez, 2007). The Dual Systems Model (DSM) says that children have a separate system for each language at the beginning stages of acquisition which interact with each other (Barlow & Enriquez, 2007; Goldstein & Gildersleeve-Neumann, 2007). In the studies of Genesee (1989) and Paradis (1987, 2001), it is maintained that children have separate sets of phonemes, phonological rules, and lexicons (as cited in Goldstein, 2004). The Interactional Dual Systems Model (IDSM) asserts that there are two separate systems present at birth which mutually influence each other (Goldstein & Gildersleeve-Neumann, 2007). Researchers will adhere to the IDSM in this study. Barlow and Enriquez (2007) clarify that certain phonological errors may exist only for bilinguals and may not be used by monolinguals. For this reason, it is not appropriate to use assessment tests or data normed on monolingual speakers (Goldstein, 2004). A bilingual child acquires each language differently. If the bilingual child has a phonological disorder, s/he will exhibit phonological processes in both languages; although they will not necessarily be the same errors (Barlow & Enriquez, 2007; Fabiano, 2007). Goldstein (2004) agrees, stating that for bilingual children to be diagnosed with a phonological disorder, processes of both languages must be analyzed. A deficit must exist in both languages to diagnose a phonological disorder in bilingual speakers (Roseberry-McKibbin, 2001). A phonological disorder is an impaired comprehension of the sound system of language, and the rules that govern the sound combinations (ASHA, 1993). A person is considered to have a phonological disorder if s/he experiences difficulties acquiring a target sound system in language EFFECT OF SPANISH ON ENGLISH CLUSTER REDUCTION 8 (Barlow & Enriquez, 2007). “There is some evidence that the phonological system of bilingual speakers develops somewhat differently from that of monolingual speakers of either language” (Goldstein & Washington, 2001, p. 153). Therefore, limited phonological proficiency in one of the two languages should not be considered a disorder. “If a child has a fundamental languagelearning problem, delay, or disorder, it will be apparent across both languages” (Fabiano, 2007, p. 23). Research shows that a similar rate of achievement of developmental milestones exists in language acquisition for bilinguals and monolinguals. A person who has a lower level of competency in one of the two languages might be perceived as having disordered speech; however, it might be a reflection of language dominance rather than phonological development (Barlow & Enriquez, 2007). “The skills of bilinguals are commensurate with, although not identical to, those of their monolingual peers.” This continues to be true of children with language disorders (Goldstein & Gildersleeve-Neumann, 2007, p. 14). Since there has been such a great influx of Spanish speakers in the United States, there is an increasingly large Spanish-English bilingual population. As previously stated, research on bilingual development and disorders is lacking, specifically on phonological disorders in SpanishEnglish bilingual children (Goldstein, 2004). The prevalence of phonological disorders in these bilingual children is approximately 10% in the preschool and school-age population (Gierut, 1998). Some examples of phonological processes that affect Spanish-English bilinguals are cluster reduction, final consonant deletion, gliding, initial consonant deletion, and fronting (Fabiano, Goldstein, & Washington, 2005). In this study, researchers will focus on cluster reductions in Spanish-English bilingual children. According to the Manual of Articulation and Phonological Disorders, cluster reduction is an error pattern in which a consonant or consonants in a consonant cluster are deleted (Bleile, EFFECT OF SPANISH ON ENGLISH CLUSTER REDUCTION 9 2004, p. 212). Consonant clusters are rare in Spanish, yet common in English (Gillam & Gorman, 2003). The results of research (Chávez-Peón et. al., 2012) showed that two Spanish-English bilingual children exhibited few or no consonant clusters; that is, most consonant clusters were deleted. For example, Spanish speakers that display cluster reduction may produce /fío/ for /frío/ or /kuato/ for /kuatro/; while English speakers may produce /pun/ for /spun/ or /tʊk/ for /trʊk/. The research of Davis, Gildersleeve-Neumann, Kaster, and Pena (2008) explains that this occurs due to a low rate of closed syllables and clusters, as well as more constrained cluster types in Spanish. Therefore, the gaps in research on cluster reduction are increasingly important to consider because of the expansion of the Spanish-English population in the United States. Over the past three decades, the population of Spanish-English speakers has rapidly increased (U.S. Department of Commerce, United States Census Bureau, 2013). There has been significant research addressing the syntactic and lexical development of this population; however, there is a lack of information about language development and phonological processes (Goldstein, 2004). While final consonant deletion, initial consonant deletion, gliding, and fronting have been investigated, research of the phonological process of cluster reduction remains underdeveloped (Goldstein, 2004). Furthermore, most research focuses on monolingual Spanish and English speakers. The purpose of this study is to focus on bilingual phonological disorders, specifically cluster reduction in bilingual Spanish-English speakers. To determine the effect of the Spanish language on the English language in cluster reduction, a mixed-methods quasi-experimental and qualitative design will be implemented in a Spanish-English immersion program at an elementary school. The following question will be addressed: EFFECT OF SPANISH ON ENGLISH CLUSTER REDUCTION 10 Do Spanish-English bilingual children have difficulty producing clusters in English due to limited clusters in the Spanish lexicon? EFFECT OF SPANISH ON ENGLISH CLUSTER REDUCTION 11 Method The researchers will be four graduate students who will receive their Masters in Communication Disorders with a focus in Speech-Language Pathology with completed coursework in phonetics and articulation. Two of the graduate student researchers will be bilingual Spanish-English speakers. These researchers will administer the Spanish assessment; whereas the other two researchers will administer the English equivalent. Additionally, a clinical supervisor from the department of Communication Disorders will oversee the project. Participants Researchers will survey the Greater New Orleans area for an ideal bilingual school campus. Researchers anticipate that J.C. Ellis, a local elementary school which offers a track in Spanish immersion, will meet the qualifying criteria for the study. The inclusion/exclusion criteria will be that the student must be a first generation native Spanish speaker who has been proficient in English for at least a year and experiences 40-60% English-Spanish input and output. According to Pearson, Fernandez, Lewedeg and Oller (as cited in Barron-Hauwaert, 1997), a balanced bilingual needs 40-60% exposure in each language. Researchers will look for a minimum of 20 participants for the study. The school will be contacted to obtain permission to conduct research. Following administrative approval, information packets will be sent to sixty families of second graders. The packets will include a description of the study and a request for consent form to be completed should they agree to let their children participate in the study. A questionnaire (inquiring the date of birth, age, languages spoken both in the household and otherwise, percentage of time of input and output in each language, how well the child is understood in Spanish by different audiences EFFECT OF SPANISH ON ENGLISH CLUSTER REDUCTION 12 [e.g. caregivers, friends, strangers], whether the child has exhibited errors in Spanish or English and in what contexts, whether there are a greater number of errors since the child began learning English, country of origin, as well as a checklist of developmental milestones and medical history) will be included in the package. Additionally, homeroom teachers will receive a questionnaire requesting information about English and Spanish language usage at school. All participating children will be of Hispanic descent, with most students specifically of Mexican, Puerto Rican, and/or Cuban origin due to the demographics of the Hispanic population in the Greater New Orleans metropolitan area (U.S. Department of Commerce, United States Census Bureau, 2013). Additionally, researchers will perform an audiology screening on each child. Children must pass the screening within normal hearing range to be accepted. Children who meet the aforementioned criteria will be included in our study. Procedures This study will utilize a mixed-methods quasi-experimental and qualitative design to measure the amount of cluster reduction exhibited in English by bilingual Spanish-English speakers. Researchers will obtain a comparison of cluster reduction errors in both English and Spanish using the Contextual Probes of Articulation Competence (CPAC) in both languages to describe this phonological process as it exists within their individual language skills. Researchers will administer the CPAC portion of the Secord Contextual Articulation Test (S-CAT) to the participants to evaluate the production of clusters in English. The S-CAT, published in 1997, analyzed the production of English language phonemes across phonetic and phonological contexts, examine performance across different speech production levels, and plan intervention. It will consist of three probes: The Contextual Probes of Articulation Competence EFFECT OF SPANISH ON ENGLISH CLUSTER REDUCTION 13 (CPAC), Storytelling Probes of Articulation Competence (SPAC), and Target Words for Contextual Training (TWCT). For the purposes of this investigation, researchers will only employ the use of CPAC which tested persons aged 4;0 into adulthood. The CPAC cluster reduction probe elicited 96 responses. There will be 72 word-level (28 initial clusters, 28 medial clusters, and 16 final clusters) and 24 sentence-level instances of cluster reduction. The probe elicited majority of phoneme combinations across sounds using different manner of articulation. . It includes several types of clusters that sample prevocalic and postvocalic clusters as well as clusters with varying prevocalic and postvocalic syllable junctures. Researchers will provide a visual (e.g. picture card of spoon) and verbal (e.g. spoon) model of probe items. The participant will repeat the model. Responses will be recorded on the test protocol. A “1” will be recorded for correct responses and a “0” for incorrect responses. Incorrect responses will be noted if a participant receives a “0.” After completion of the Contextual Probes of Articulation Competence, the researchers will administer the Spanish equivalent, the Contextual Probes of Articulation CompetenceSpanish (CPAC-S) to the participants. This will be done to evaluate their articulation skills and phonological patterns in Spanish. The CPAC-S, a norm-referenced test designed for ages 3;08;11, probed the production of all Spanish phonemes in a variety of phonetic and phonological contexts. Similarly to the S-CAT, the researchers will administer only the cluster reduction probe of the CPAC-S. The administration and scoring procedures of the CPAC-S will correspond to that of the CPAC. Additionally, researchers will obtain brief language samples from each participant in English. The samples will be analyzed for Percentage of Consonants Correct (PCC) and Type Token Ratio (TTR). The PCC will measure the number of correct consonants in a sample. It will EFFECT OF SPANISH ON ENGLISH CLUSTER REDUCTION 14 be calculated by dividing the number of correct consonants by the number of total consonants and multiplying by 100. Type Token Ratio will measure the variety of words in a person’s language. Researchers will extract the TTR by dividing the number of different words by the number of total words. The TTR will verify that the student’s speech includes a variety of consonant clusters, and the PCC will measure the accuracy of the consonant cluster production. Data analysis Researchers will organize data from language samples and assessments into categories labeled by phonemic context to determine the frequency of cluster reduction. Standard scores from both the CPAC and CPAC-S will be compared. The data will be organized in bar graphs comparing both standard scores for each consonant cluster position. The data will be organized in a bar graph demonstrating the average standard scores for each of the following consonant cluster positions: initial, medial, and final at the word level, as well as sentence level. Investigators will create a comprehensive bar graph that will summarize the data of all participants by comparing standard score means across positions in each language. The comprehensive graph will be formatted as follows: EFFECT OF SPANISH ON ENGLISH CLUSTER REDUCTION 15 Additionally, the researchers will note cluster reductions observed in all positions across the language sample. Instruments Data will be obtained by researchers during administration of both the CPAC and CPAC-S in order to determine in which contexts students will present cluster reduction errors. The record form for the CPAC will be as follows: EFFECT OF SPANISH ON ENGLISH CLUSTER REDUCTION Reliability and Validity The evaluations and language samples will be videotaped. The clinical supervisor will compare twenty percent of the tests to ensure inter-rater reliability of 99% for English and Spanish assessments. Validity will be established by compiling a verbatim transcription of the 16 EFFECT OF SPANISH ON ENGLISH CLUSTER REDUCTION 17 language sample from a video recording. Researchers will archive questionnaires which will be completed by parents and teachers. EFFECT OF SPANISH ON ENGLISH CLUSTER REDUCTION 18 References ASHA Ad Hoc Committee on Service Delivery in the Schools. (1993). Definitions of communication disorders and variations. Asha, 35 (Suppl. 10), 40-41. Barlow, J. A., & Enríquez, M. (2007). Theoretical perspectives on speech sound disorders in bilingual children. Perspectives on Communication Disorders and Sciences in Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Populations, 14(2), 3-10. doi:10.1044/cds14.2.3 Barron-Hauwaert, S. (2004). Language strategies for bilingual families: the one-parent-one-language approach. Tonawanda, NY: Multilingual Matter Ltd. Bleile, K. (2004). Manual of Articulation and Phonological Disorders Infancy through Adulthood. (2nd ed.) New York: Thomson Delmar Learning Bilingualism [Def. 1]. (n.d.). Merriam-Webster.com. Retrieved September 29, 2013, from http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/bilingualism. Chávez-Peón, M. E., Bernhardt, B. M., Adler-Bock, M., Ávila, C., Carballo, G., Fresneda, D., Lleo, C., Mendoza, E., Perez, D., & Stemberger, J. P. (2012). A Spanish pilot investigation for a crosslinguistic study in protracted phonological development. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 26(3), 255-272. Davis, B., Gildersleeve-Neumann, C., Kaster, E., & Pena, E. (2008). English speech sound development in preschool-aged children from bilingual English Spanish environments, 39, 314-328. doi:10.1044/0161-1416 (2008/030) Fabiano, L. C. (2007). Evidence-based phonological assessment of bilingual children. Perspectives on Communication Disorders and Sciences in Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Populations, 14(2), 21-23. doi:10.1044/cds14.2.21 Fabiano, L., Goldstein, B., & Washington, P. (2005) Phonological skills in predominantly EFFECT OF SPANISH ON ENGLISH CLUSTER REDUCTION English-speaking, predominantly Spanish-speaking, and Spanish-English bilingual children, 36, 201-218. doi: 10.1044/0161-1461 (2005/021). Genesee, F., Nicoladix, N., & Paradis, J. (1995). Language differentiation in early bilingual development. Journal of Child Language, 22, 611-631. Gierut, J. (1998). Treatment efficacy: functional phonological disorders in children. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 41, S85-S100. Gillam, R. & Gorman, B. (2003). Phonological awareness in Spanish: A tutorial for speech language pathologists. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 25, 13-22. doi: 10.1177/15257401030250010301. Goldstein, B. A. (2004). Bilingual language development & disorders in Spanish-English speakers. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co. Goldstein, B., & Gildersleeve-Neumann, C. (2007). Typical phonological acquisition in bilinguals. Perspectives on Communication Disorders and Sciences in Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Populations, 14(2). 11-16. doi:10.1044/cds14.2.11 Goldstein, B., & Washington, P. S. (2001). Clinical forum. an initial investigation of phonological patterns in typically developing 4-year-old spanish-english bilingual children. Language, Speech & Hearing Services in Schools, 32(3), 153. National Clearinghouse for English Language Acquisition (2011). What languages do English learners speak? NCELA Fact Sheet. Washington, DC. http://www.ncela.us/files/uploads/NCELAFactsheets/EL_Languages_2011.pdf Ortman, J. M., and Shin, H. B. (2011). Language Projections: 2010 to 2020. U.S. Department of Commerce, United States Census Bureau. Retrieved from website: http://www.census.gov/hhes/socdemo/language/data/acs/Shin_Ortman_FFC2011_pape 19 EFFECT OF SPANISH ON ENGLISH CLUSTER REDUCTION r.pdf. Paradis, J. (2001). Do bilingual two-year-olds have separate phonological systems? International Journal of Bilingualism, 5, 19-38. Paradis, M. (1987). The assessment of bilingual aphasia. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Roseberry-McKibbin, C. (2001). The source for bilingual students with language disorders. East Moline, IL: LinguiSystems. U.S. Department of Commerce, United States Census Bureau. (2013). Appendix table 2. margins of error 1 for table 2: languages spoken at home for the population 5 years and over. Retrieved from website: www.census.gov. U.S. Department of Commerce, United States Census Bureau. (2013) U.S. Census Bureau: State and County QuickFacts. Retrieved from website: http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/22/2255000.html. 20