Grounded Theory in Practice

advertisement

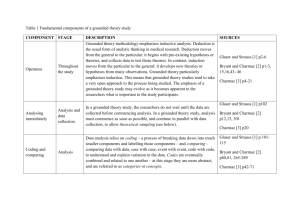

Grounded Theory in Practice Abstract Grounded theory (GT) is becoming more popular as a research methodology in several fields including HRD. Although is still considered a niche methodology we suggest that more qualitative research is needed across all areas. A gap was found relating to studies which explain how to use GT in practice. Thus, this paper intends to be an important contribution especially to research students and academics interested in employing GT in their projects. This paper presents two doctoral research studies in which GT was employed successfully. The first study used GT to explore the relationship development, through direct marketing (DM), between customers and training services companies. Thirty semi-structured interviews were conducted with training / HRD directors. The second study employed GT in an indepth one case study scenario, analysing Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) practices in a UK utility business. One of its aims was to explore employees’ perceptions as part of an internal feedback system. It is relevant to emphasise that both pieces of research were intrinsically different. However, there was an essential aspect in common. The key aim in these studies was to explore what was “behind the surface”, to understand the insights that interviewees gave to each theme in particular. By comparing and contrasting two cases we illustrate how GT can be used in different academic disciplines and identify the challenges that this approach brings. Keywords: Grounded Theory, Qualitative Research, Interviews, Case Study, Marketing, Corporate Social Responsibility Acknowledgments The work reported in this paper was co-financed by FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, Portugal (PEst-OE/EME/UI4005/2011) and carried out within the research centre Centro Lusíada de Investigação e Desenvolvimento em Engenharia e Gestão Industrial (CLEGI). Introduction It seems that there is an increasing need of employing a qualitative methodology. It is obviously important to gain quantitative insights, but it is crucial to complement this “quantification” with the understanding of how and why certain phenomena actually occur. Grounded theory (GT) is becoming more popular in academia, although still considered to be a niche methodology. This paper discusses two pieces of research, both substantive studies for two doctoral theses and both of which successfully employed grounded theory. These studies suggest that a grounded theory methodology can advance innovative and novel research. This paper is structured as follows. First, a literature review is presented on GT research. Then, the two research studies, which employed GT, are discussed. The paper ends with some conclusions and implications of using GT. Literature Review GT was chosen for both research studies that are discussed in this paper, since the aim was to gather interviewees’ perceptions, thoughts and feelings about each topic. 1 In order not to be restricted to testing any kind of framework or theory and to keep an open mind, GT was used so that the concepts emerged from the data ‘naturally’. The next sections will provide a brief introduction into GT and how it is relevant to research nowadays. The Introduction and History of Grounded Theory GT was initially developed by Glaser and Strauss (1967) in order to address “the discovery of theory from data” (p. 1). The main aim of GT is to establish an approach for theory to emerge from the data of social research. It was developed during a time, when qualitative data analysis was rather unpopular (Charmaz, 2006, p. 4) and also under scrutiny for a lack of scientific rigour (Turner, 1981, p. 225, 1983, p. 333; Goulding, 2005, p. 295). Hence, Glaser and Strauss had particularly qualitative research in mind for which they wanted to provide a “systemization of the collection, coding and analysis” in order to generate theory (Glaser and Strauss, 1967, p. 18). The defining components of GT are as follows (Charmaz, 2006, p. 5): Simultaneous involvement in data collection and analysis Constructing analytic codes and categories from data, not from preconceived logically deduced hypotheses Using the constant comparative method, which involves making comparisons during each stage of the analysis Advancing theory development during each step of data collection and analysis Memo-writing to elaborate categories, specify their properties, define relationships between categories, and identify gaps Sampling aimed representativeness Conducting the literature review after developing an independent analysis toward theory construction, not for population After their joint publication Glaser and Strauss went on to continue developing GT in different ways that led to a methodological split (Melia, 1996; Charmaz, 2000; Boychuk Duchscher and Morgan, 2004; Goulding, 2005; Kelle, 2005; Charmaz, 2006; Mills et al., 2006). Whereas Glaser was an advocate of conducting GT in its purest form by letting the theory emerge from the data and returning it for verification, Strauss was in favour of a more structured conceptualisation by using a coding paradigm to guide the analysis. This debate that was subsequently coined “emergence vs. forcing debate”, led to two main streams of GT (Glaser, 1992; Boychuk Duchscher and Morgan, 2004; Kelle, 2005). Glassian grounded theory Glaser believed in the purely inductive nature of GT to “absorb the data as data” with preconceptions of forcing results (Glaser, 1992, p. 11). This version of GT is defined as: 2 “a general methodology of analysis linked with data collection that uses a systematically applied set of methods to generate an inductive theory about a substantive area” (Glaser, 1992, p. 16) It can therefore be applied both to quantitative and qualitative data. It is important to note that GT is “not finding, but rather an integrated set of conceptual hypotheses” that in practice are often considered as findings (Glaser, 1998, p. 3). Moreover, Glaser (1998) states that although it is in the nature of every researcher to force categories from the data. It is possible to overcome it if the researcher “… suspends what he knows, keeps studying the data, conceptualizes and constantly compares. He gets skilled at this. It is a ‘degree of’ achievement”. (p. 81) This strand of GT employs mainly constant comparison, in which the new data is compared with existing data to find similarities and differences. These insights are then used to develop and refine the categories used in the analytical process (Glaser and Strauss, 1967; Glaser, 1992; Charmaz, 2006). When Strauss started to develop his own version of GT, Glaser was very critical of the new direction as, from his point of view, it contradicts the basic notion of GT for the theory to emerge from the data and not to be forced into categories (Glaser, 1992; Kelle, 2005). Straussian grounded theory Strauss and Corbin followed a different path in carrying the development of GT forward (Strauss and Corbin, 1998). The main idea of Strauss and Corbin is that while they acknowledge that the researcher “allows the theory to emerge from the data”, it is still necessary to provide “some standardization and rigor to the process” (Strauss and Corbin, 1998, p. 13). This is done by a formalisation of the data analysis and theory building process, which they structure into coding (open coding, axial coding, and selective coding), theoretical sampling, and memo writing (Strauss and Corbin, 1998; Boychuk Duchscher and Morgan, 2004; Charmaz, 2006). Despite the vehement criticism of Strauss and Corbin’s approach by Glaser (1992), it is the more prominent and used stance of grounded analysis (Bryman and Bell, 2003, p. 428). Grounded theory as inductive research As GT is an inductivist research, it requires that the scientist initiates the research without any preconceived ideas and with an open mind. However, this does not mean that it is necessary to have no a priori knowledge whatsoever, which in fact is hardly possible (Heath and Cowley, 2004; Goulding, 2005, p. 296; Kelle, 2005). Instead, it is necessary to carefully prepare the research, while maintaining the openness to let the theory emerge from the data. Glaser and Strauss (1967) confirm this by stating that it is unrealistic that the researcher “approach[es] reality as tabula rasa” and that it is vital to “have a perspective that will help him see relevant data and abstract significant categories” (p. 3). 3 Moreover, the use of existing literature and whether to conduct a literature review before the data collection and analysis is debatable (e.g. McCann and Clarke, 2003; Charmaz, 2006). Glaser (1992) claims that any prior literature review puts constraints the generation of categories and that it should only be carried out as part of the data analysis. On the other hand, Strauss and Corbin (1998) are of the opinion that an initial literature review enhances the theoretical sensitivity, although the main review is conducted at a later stage in order to support the emerging themes. Saunders et al. (2000) also stress that grounded theorists do not start research without a competent level of knowledge in the area and that a clearly defined purpose is important when initiating the research. This needs to be flexible in order to be altered if the data requires doing so. Interestingly, apart from building a sound basis, a good preparation, for instance a good literature review, creates much more distance than it sacrifices for the openness required by GT (McCraken, 1991). The main challenge here is therefore balancing “between drawing on prior knowledge while keeping a fresh and open mind to new concepts as they emerge from the data” (Goulding, 2005, p. 296). Coding in grounded theory The way in which data is coded in a grounded analysis depends heavily on which version of it is being used (see Table 1). In the original work of Glaser and Strauss (1967) only coding for categories as part of the constant comparison is being used. Since then Glaser has vehemently opposed any coding procedure that goes beyond substantive codes and theoretical codes. Substantive codes are developed during initial/open coding and theoretical coding then helps to develop relationships between substantive codes and to put together the fractured data, for which Glaser has provided 18 overlapping code families (Boychuk Duchscher and Morgan, 2004; Kelle, 2005). Strauss and Corbin (1998) add another level to the coding process. Axial coding is used to relate categories to their subcategories to “form more precise and complete explanations about phenomena” (p. 124). It also reassembles the data that was fractured during the process of the initial coding, providing some coherence to the emerging analysis (Charmaz, 2006, p. 60). This provides a more general paradigm model rather than Glaser’s approach to use a list of sociological terms to identify and relate categories. The axial coding is then followed by selective coding, where the core categories are chosen and then related to other categories. 4 Strauss (1998) and Corbin Glaser (1992), Glaser (1998) Initial coding Open coding Use of analytical technique Substantive coding Data dependent Intermediate phase Axial coding Reduction and clustering of categories Continuous with previous phase Comparisons, with focus on data, become more abstract, categories refitted, emerging frameworks Final development Selective coding Detailed development of categories, selection of core, integration of categories Theoretical Refitting and refinement of categories which integrate around emerging core Theory Detailed and dense process fully described Parsimony, scope and modifiability Table 1: Comparisons of Grounded Theory Coding and Data Analysis Source: Heath and Cowley (2004, p. 146) Criticism to grounded theory Naturally, there are some criticisms and pitfalls related to the use of GT that have to be kept in mind. First of all, GT is considered to be more suitable for qualitative data obtained from semi-structured or unstructured interviews, observation, case study material or other documentary sources rather than for instance looking at larger scale aspects of social phenomena, like demographic trends (Turner, 1981, p. 227). Furthermore, the quality of the research outcome is more dependent on the quality of data and understanding that is developed during the research project, more than for most other modes of social inquiry. Seldén (2005) points out a number of issues that a researcher, who is applying GT, needs to be aware of: technically complicated coding procedures, contextual sensitivity, a priori knowledge and preparation, and level of sophistication of the theories (p. 126). Most of these criticisms lie within the theoretical sensitivity and the view that the concepts are not emerging from the data, but that they depend on the knowledge, experience, and skills of the researcher and also the knowledge that had been acquired beforehand and the preparation of the research. Therefore the position of the researcher in creating knowledge has been largely neglected in the original GT writings. In addition to this, the research position and the resulting empiricist bias and also the use of qualitative software packages can lead to a disconnection from the context and fragmentation of the data when incidents are 5 coded (Bryman and Bell, 2003, p. 434; Seldén, 2005, p. 126). A widely expressed ramification of the coding process according to Strauss and Corbin (1998) is that it is very technical and that the coding becomes a goal in itself whilst threatening the creative process that is at the heart of GT. While all of the above mentioned objections are valid, they need to be taken into consideration, but do not present a major obstacle in applying GT (Turner, 1981). In fact, GT proved to be an appropriate approach to this research considering the emerging results, which will be presented in the next section. Data Analysis Process GT in all its details can be a very complex methodology. However, Glaser (1998) calls for researchers to stop talking about it and just get on with doing it, especially because “well done grounded theory justifies itself“ (p. 19). Heath and Cowley (2004) suggest to less worry about “doing it right” and just “adhere to the principle of constant comparison, theoretical sampling and emergence” and then to identify the most suitable stance of GT (p. 149). Moreover, they stress that qualitative analysis is a cognitive process and therefore subject to each researcher’s individual style and reflects a personal point of view and by no means a grand theory. This also applies to choosing the most appropriate version of GT. Grounded Theory in Practice Two research projects were carried out, the first finished in 2009, the second in 2010. The way in which GT was applied in each of them will be explained next. Study 1 The main aim of this study was to explore if and how direct marketing (DM) can contribute to the development of relationships with customers in the training sector based in Portugal. Significantly, this study focused only on the customers’ perspective and experiences. Thus, this research explored qualitatively customers’ perceptions on the link between DM and relationship marketing (RM), in a businessto-business context, using a GT approach. To the best of our knowledge, no other empirical study was found examining this particular combination. The data comprised thirty semi-structured qualitative interviews. The interviews followed a checklist guide, which was tested in three pilot interviews and then refined for the major data collection. The argument of Clough and Nutbrown (2002) was followed in the sense that the “schedule guided the interview but did not dictate the path” (p.105). The research sample was purposive, consisting of training customers, specifically 24 training directors and six training participants from 30 different companies in Portugal. The interviews were conducted in Portuguese, transcribed, and then translated into English. Since this study aimed to explore interpretations and meanings of an underresearched topic, specifically how training customers perceive the process on the relationship development through DM, GT was chosen (Stroh, 2000). Furthermore, GT is considered especially adequate and efficient to analyse qualitative data. Thus, the nature of this study seemed to require this type of analysis, “grounded in customers’ data” (Glaser and Strauss, 1967). The seven stages grounded approach of Easterby-Smith, Thorpe and Lowe (2002) was employed in the data analysis. This rigorous grounded analysis approach “fit” closely with the GT “type” of Strauss and 6 Corbin (1998) since several procedures were followed. Memos, diagrams and tables based on Miles and Huberman (1994) were used, complementing the analysis process. Moreover, GT allowed changes across interviews, some questions being added in certain cases when it was necessary to follow some “new” paths/ideas. The way in which these seven stages were followed in practice was based on Elliott (1998) and is explained in Table 2. Familiarisation with data In this first stage transcripts were read while listening to the tapes. The aim was to check carefully if transcripts were correctly made by the company in charge of them. Some word errors were corrected and some spaces filled in. Total confidence on the interview transcripts was achieved. Reflection on the This stage was done at same time as the first. While reading interview data the transcripts and listening to the tapes, some notes in a memo were taken, namely about impressions on interviewees’ meanings, voice tones, limitations and other general observations. Conceptualisation Many concepts appeared at this stage. All the interviews transcripts were codified, 46 codes being developed. Some pieces of data were in more than one code. The most interesting ideas were underlined and key quotes highlighted in green. Cataloguing At this stage data were grouped by code in the computer (word concepts programme). This enabled a close familiarisation with the data. Re-Coding Data were re-read and re-grouped by code, cutting some of them and making some changes in codification of some pieces of data. At this stage codes were reduced to 28. In this phase, tables based on Miles and Huberman (1994) were constructed, with all the codes in the columns, and the interviewees’ summarised answers in the rows. GT includes “the ‘constant comparison’ method” (Goulding, 2005, p. 297), which was followed at this stage, comparing the answers of each interviewee by code. Linking Several patterns and relationships were found at this stage. The tables done in the previous stage, “reducing data” based on Miles and Huberman (1994) proved to be particularly useful in order to compare interviewees’ answers and to have a complete picture of the whole data. Re-Evaluation Transcripts were read for the last time. Some points of the analysis were improved, some details and quotes being added. At this final stage, four main areas emerged distributed by 10 themes (representing four parts in the two findings chapters). A diagram with these main findings was designed, which was then followed in the data analysis chapters. This diagram was a crucial element in the GT process, being extremely helpful in facilitating writing the findings. Table 2: Data analysis of study 1 7 Complementary analysis tools were used, proving to be really helpful in facilitating and complementing the Easterby-Smith et al. (2002) seven stages grounded analysis approach. More specifically, the list of codes, the tables based in Miles and Huberman (1994), the memos (Goulding, 2002) and the diagram (Strauss and Corbin, 1998) were used. The key findings that emerged from the GT research were that DM appeared to have two key roles: (1) to establish a relationship between customers and training companies, this being dependent on the relevance of DM to the recipients’ jobs/activities combined with the credibility of the DM source; and (2) DM has a conditional role in the relationship development between customers and training companies. DM only has a role in developing relationships if it is relevant to customers’ training needs combined with positive perceptions of the past training performance in customers’ minds. These perceptions are linked to quality and satisfaction, customers making an immediate association between the DM source and past training performance. Moreover, other findings emerged, namely two different customer segments, one more relational, the other more transactionaloriented, the key difference between them being the like/dislike for personal contacts. Finally, completely different customer perceptions regarding DM received either in a BTB or in a BTC context strongly and unexpectedly emerged. These findings demonstrate clearly the immense advantages of employing GT, mainly that of allowing the researcher to go further than envisaged, contributing significantly to the DM and RM literature and practices. Study 2 The second study investigated the current state and past development of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) practices in a UK utility company. There are calls to look at CSR from a different perspective (Gladwin et al., 1995; Bebbington, 2007) and Gladwin et al. (1995) suggested that the very nature of CSR forces management research toward interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary modes of inquiry. The study consisted of a two-phased single case study approach. The first phase was an in-depth case study in a business organisation with recognised CSR credentials. This organisation was a UK water business, which operates in an industry characterised both by a high level of regulation and a significant ecological relevance. This phase consisted predominantly of semi-structured interviews, yet also considered some documentary evidence. For the second research phase stakeholders of the case study company were interviewed in order to gain a more holistic perspective of the dynamics of implementing CSR. In order to provide a significant contribution to the existing research a grounded research approach was chosen. This provided the possibility of taking a broader perspective than previous research, which employed existing theoretical frameworks like stakeholder theory or legitimacy theory, which have frequently been used in researching CSR. When identifying the most suitable approach to GT for this study, Strauss and Corbin (1998) seemed more suitable and appealing because of the more structured and detailed procedures that provide substantially more guidance than when following Glaser and Strauss (1967). In addition, it is suggested that the version of GT should be selected, which fits the researcher’s paradigm of inquiry (Goulding, 1999). Strauss and Corbin (1998) assume an “objective external reality”, but also acknowledge respondents’ “views of reality” (Charmaz, 2000, p. 510), which is congruent with the stance taken in this study. 8 After beginning to conduct the research using GT according to Strauss and Corbin (1998) it became apparent that this approach can be highly complex due to the systematic coding techniques, which Goulding (1999) confirms. Bearing in mind the previous comments on GT being a subjective cognitive process, I started to modify existing approaches and adapted them to how I thought it would be most appropriate for my research. Furthermore, Glaser and Strauss (1967) explicitly state that they do not want to coerce the theory’s acceptance by the reader and call for readers to use the proposed GT strategies in a flexible way. This is confirmed by Charmaz (2006) and Turner (1981), who both suggest that GT is not a methodology that should be followed dogmatically, but instead just outlines a proposition for a procedure. Hence, the applied procedures and strategies used in this thesis draw on a number of different influences (Turner, 1981; Charmaz, 2000; Bryman and Bell, 2003; Heath and Cowley, 2004; Jones et al., 2005; Charmaz, 2006) bearing in mind that they all have the fundamental GT strategies as described in one way or another by Glaser and Strauss (1967) and Strauss and Corbin (1998). The GT research process was a cyclical one and included the stages as illustrated in Table 3. Preparation The first stage included the development of the research questions. The main role of the research questions is to direct the research and set the boundaries. Strauss and Corbin (1998) pointed out that for doing that, the research questions need to be formulated in a way that they are setting the frame in order to develop a theory and to investigate a phenomenon in depth. In directing the research, the research questions are also constantly guiding the literature review that is necessary to build a basis of knowledge in the substantive area and also contribute to the theoretical sensitivity, i.e. the researcher’s ability to generate the theory and see relevant data (Glaser and Strauss, 1967, p. 46; Kelle, 2005). Data collection The first set of codes was based on the literature review and and initial consciously kept as generic as possible in order to avoid preconceptions limiting analysis. In the initial coding (or open coding coding according to Strauss and Corbin) the data is used to identify concepts and their properties and dimensions are discovered (Strauss and Corbin, 1998). Data collection In this stage the data collection and analysis continued and coding simultaneously. After conducting the interviews, they were subsequently transcribed and coded line by line as described for the initial coding. As the number of interviewees increased, the codes were constantly refined. An essential tool in applying GT is constant comparison. Incidents and statements were compared within the same interview and also with different interviews, which then allowed identification, linking, and focusing on the important aspects in order to extract them into the theory generation, but also to use these for the generation of new codes. What followed was the focused/selective coding, in which the codes were 9 identified that produced the most amount of data but also the most relevant data. This guided the structure of the analysis and made the work more focused and goal directed. The codes that produced data to a lesser extent were by no means discarded, hoping that they might at some point produce interesting and relevant insights as well. The end of the data collection and analysis cycle is determined by the theoretical saturation of the codes (Glaser and Strauss, 1967, p. 111). This means if after analysing different interviews, codes become saturated, meaning that collecting more data does not provide new theoretical insights (Charmaz, 2006, p. 113), it is unnecessary to continue. Writing up and At the end, the resulting data needed to be transformed into an presentation analytical text, which proved challenging, as the analysis resulted in a very large document. Table 3: Data analysis of study 2 The key findings that emerged from the GT research were related to the conceptualisation of corporate social responsibility. A number of different theories and perspectives have been applied to the implementation of CSR practices in organisations. For instance, institutional theory, legitimacy theory, organisational theory and stakeholder theory are popular among researchers. Moreover, the different perspectives that were used to analyse CSR include, among others, accounting, marketing, human resources. While all these approaches have led to valuable insights in their own right, they have also obstructed finding new approaches to unsolved problems. As pointed out previously, this is mirrored by academics calling for new perspectives. Specifically, this research identified a systemic complexity and that it is necessary to take a more comprehensive research approach to reflect such complexity. The internal organisational dynamics and the external stakeholder pressures and interactions were important in shaping the CSR implementations. Particularly in terms of the organisational value system, which is determined by the societal perception, the complex interdependencies are evident. Conclusions and Implications The first study used the Easterby-Smith et al. (2002) grounded analysis approach. The key findings that emerged from this research were that DM appeared to have two key roles: (1) to establish a relationship between customers and training companies, this being dependent on the relevance of DM to the recipients’ jobs/activities combined with the credibility of the DM source; and (2) DM has a conditional role in the relationship development between customers and training companies. DM only has a role in developing relationships if it is relevant to customers’ training needs combined with positive perceptions of the past training performance in customers’ minds. These perceptions are linked to quality and satisfaction, customers making an immediate association between the DM source and past training performance. The second study employed GT approaches according to Glaser and Strauss (1967), Strauss and Corbin (1998) and Charmaz (2006). The key findings were related to the 10 conceptualisation of CSR within a business organisation. A number of different theories and perspectives have been applied to the implementation of CSR practices in organisations, such as institutional theory, legitimacy theory, organisational theory and stakeholder theory. Moreover, the different perspectives that were used to analyse CSR include, among others, accounting, marketing, and human resources. While all these approaches have led to valuable insights in their own right, they have also obstructed finding new approaches and lenses to unsolved problems. This is mirrored by academics calling for new perspectives to solve the social and environmental crisis. Specifically, this research identified a systemic complexity and highlighted that it is necessary to take a more comprehensive research approach to reflect such complexity. This means that in practice a joint effort by all departments is necessary. Particularly in terms of the organisational value system, which is determined by the societal perception, the complex interdependencies are evident. Both studies discussed in this paper are very different in topic, scope and the GT implementation process. Despite the different research designs the advantages of a GT research approach strongly emerged. In both cases, the use of GT allowed conducting innovative research, with new perspectives and approaches, leading to novel, interesting and rich research findings. Thus, we suggest that for both research topics, one being novel (as in the first study) and the other established (as in the second), GT can equally result in new findings and indicate further directions for future research. In terms of the execution of GT, the studies have shown that while there is some level of complexity in the analysis process, the advantage of GT is that it can be adapted to suit the individual needs and preferences of the researcher. This is a powerful aspect of GT in aiding state of the art research. References Bebbington, J. (2007). Changing organizational attitudes and culture through sustainability accounting. In: Unerman, J., Bebbington, J. and O'Dwyer, B. (Eds.) Sustainability accounting and accountability. London: Routledge. Boychuk Duchscher, J. E. and Morgan, D. (2004). Grounded theory: reflections on the emergence vs. forcing debate. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 48, 605-612. Bryman, A. and Bell, E. (2003). Business research methods, Oxford, Oxford University Press. Charmaz, K. (2000). Grounded Theory: Objectivist and Constructivist Methods. In: Denzin, N. K. and Lincoln, Y. S. (Eds.) Handbook of Qualitative Research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage. Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory, London ; Thousand Oaks, Calif., Sage Publications. Clough, P. and Nutbrown, C. (2002). A student’s guide to methodology, London, Sage. Easterby-Smith, M., Thorpe, R. and Lowe, A. (2002). Management research - An Introduction, London, Sage. Elliott, D. (1998). Organisational learning from crisis: an examination of the UK football industry 1946-97. Doctoral Thesis, UK: University of Durham Business School. 11 Gladwin, T. N., Kennelly, J. J. and Krause, T.-S. (1995). Shifting Paradigms for Sustainable Development: Implications for Management Theory and Research. Academy of Management Review, 20, 874-907. Glaser, B. G. and Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research, Hawthorne, N.Y, Aldine de Gruyter. Glaser, B. G. (1992). Basics of grounded theory analysis : emergence vs forcing, Mill Valley, Ca, Sociology Press. Glaser, B. G. (1998). Doing grounded theory : issues and discussions, Mill Valley, CA, Sociology Press. Goulding, C. (1999). Consumer research, interpretive paradigms and methodological ambiguities. European Journal of Marketing, 33, 859-873. Goulding, C. (2002). Grounded theory: a practical guide for management, business and market researchers, London, Sage. Goulding, C. (2005). Grounded theory, ethnography and phenomenology: A comparative analysis of three qualitative strategies for marketing research. European Journal of Marketing, 39, 294-308. Heath, H. and Cowley, S. (2004). Developing a grounded theory approach: a comparison of Glaser and Strauss. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 41, 141-150. Jones, M. L., Kriflik, G. and Zanko, M. (2005). Grounded Theory: A theoretical and practical application in the Australian Film Industry. Faculty of Commerce Papers. University of Wollongong. Kelle, U. (2005). "Emergence" vs. "Forcing" of Empirical Data? A Crucial Problem of "Grounded Theory" Reconsidered. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 6. McCann, T. V. and Clarke, E. (2003). Grounded theory in nursing research: Part 2 Critique. Nurse Researcher, 11, 19-28. McCraken, G. (1991). The Long Interview. Sage University Paper Series on Qualitative Research Methods, 13, 9-87. Melia, K. M. (1996). Rediscovering Glaser. Qualitative Health Research, 6, 368-378. Miles, M. B. and Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook, Thousand Oaks, Calif. ; London, Sage. Mills, J., Bonner, A. and Francis, K. (2006). The Development of Constructivist Grounded Theory. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5, 1-10. Saunders, M., Lewis, P. and Thornhill, A. (2000). Research methods for business students, Harlow, Financial Times/Prentice Hall. Seldén, L. (2005). On Grounded Theory - with some malice. Journal of Documentation, 61, 114-129. Strauss, A. L. and Corbin, J. M. (1998). Basics of qualitative research : techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory, Thousand Oaks, Calif. ; London, Sage Publications. Stroh, M. (2000). Qualitative interviewing. In: Burton, D. (Ed.) Research training for social scientists: A handbook for postgraduate researchers. London: Sage. Turner, B. A. (1981). Some practical aspects of qualitative data analysis: One way of organising the cognitive processes associated with the generation of grounded theory. Quality and Quantity, 15, 225-247. Turner, B. A. (1983). The Use of Grounded Theory for the Qualitative Analysis of Organizational Behaviour. Journal of Management Studies, 20, 333-348. 12