Reading list - Deirdre McCloskey

advertisement

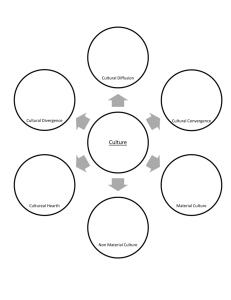

History 594 (#31131) Seminar on Ideas, Class, and Economy in World History Deirdre N McCloskey Department of History, deirdre2@uic.edu deirdremccloskey.org Tuesdays 5:00-7:50. First meeting Lincoln Hall 201; subsequently 720 S Dearborn St, Unit 206 Our task is to survey the exploding field of world history in its macro aspect—that is, histories that claim to synthesize everything (as against monographs on this or that aspect of everything). We’re going to put into discussion the ever-rising number of historical and sociological books (and a few articles) that claim to account for the patterns of world history, and especially the Great Divergence after 1800. From Montesquieu, Smith, and Marx down to David Harvey and Joel Mokyr the history of everything has usually amounted to explaining the Rise of the West, what Ken Pomeranz called the Great Divergence and I call anyway the Great Fact. And yet a vigorous counter-narrative has emerged that does not place Europe at the center of it all. Both Eurocentric and Europetal ruminations have recently proliferated to a startling degree, after William McNeill and Philip Curtin and Jack Goody and a few other pioneers in the 1970s first made big world history serious. Your leader, for example, has recently joined the fray, and we will be scrutinizing her three “ideational” books on the matter (2006, 2010, and a third forthcoming in manuscript) in some detail in the first few weeks by way of a unifying place to start our discussions. From it you will learn the strengths and weaknesses of an economic approach, and especially the central question: How much do ideas and ideology matter, and how? But the bulk of our work will be on alternatives—Marxist, for example (Wallerstein, Harvey); or cultural (Goody, Landes, and others); geographic (Diamond); Polanyan (Polanyi himself; Finley, Scott); neo-institutional (North, Greif, Robinson). A baker’s dozen or so books will be required reading for all participants (many are available secondhand cheap, of course). Order them pronto: Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation (1944). Immanuel Wallerstein, Historical Capitalism (1983). Charles Tilly, Coercion, Capital, and European States, 990-1992 (1990). Janet L. Abu-Lughod, Before European Hegemony: The World System A.D. 1250-1350. (1991). Jared Diamond, Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies (1997). Kenneth Pomeranz and Steven Topik, The Word That Trade Created: Society, Culture, and the World Economy (2nd ed., 2006). See also Pomeranz’s The Great Divergence on China’s history. 1 McCloskey’s trilogy: The Bourgeois Virtues: Ethics for an Age of Commerce (2006), Bourgeois Dignity: Why Economics Can’t Explain the Modern World (2010), and in manuscript The Treasured Bourgeoisie: How Markets and Innovation Became Ethical, 1600-1848, and Then Suspect. Douglass C. North, John Joseph Wallis, Barry R. Weingast, Violence and Social Orders (2009). Jean-Laurent Rosenthal and R. Bin Wong, Before and Beyond Divergence: The Politics of Economic Change in China and Europe (2011). Stanley Engerman and Kenneth L. Sokoloff, Economic Development in the Americas since 1500: Endowments and Institutions (2012). Joel Mokyr, The Enlightened Economy: An Economic History of Britain 1700–1850 (2011). Sheilagh Ogilvie, Institutions and European Trade: Merchant Guilds, 1000-1800 (2011). Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty (2012). Patrick Karl O’Brien, “The Contributions of Warfare with Revolutionary and Napoleonic France to the Consolidation and Progress of the British Industrial Revolution.” MS to be distributed on Blackboard, and other essays of interest I’ll put up. We will discuss these and the supplementary books (btw, my books give one view of the bibliography of the subject) in presentations, the details of which we will decide in a week or so. One or two people each session will present their critical, overstanding reflections on an important book in one of the traditions: think of being what the Swedes call in their PhD exams “opponents,” who summarize and then lead discussion on the book. We will decide early on who will report on what, consulting your interests. Come to the first meeting with ideas, especially if you have some preferences or expertise. The seminar discussion will be as deep and as wide-ranging as we can make it. But of course, aside from the skeleton of required books, not everyone will need to read every page of every book we discuss—an impossible task anyway, considering the proliferation I speak of. (I have a piece on reading for one’s own uses books of such a character, which I will post on Blackboard; read it first.) After the discussion in which you yourself have starred you will write up and distribute by Blackboard to the class a final report. By the end we all have a collection of discussion papers on the books, suitable for preparing lectures of your own in your own World History course. We are trying to reach a reasonable grasp of a big literature. It will perhaps give you a framework for detailed work in your thesis (whatever your field) and will certainly give you the background to teach an undergraduate course in the subject. If you are working in American labor history, for example, you will want to understand more broadly the role of labor markets in history—the claims of Marxist writers being only one of several possibilities, others being economics or legal studies or institutional sociology. That is, you’ll want to know of alternatives in labor history, even if in the end you choose to focus on one. Similarly, if you are working in Latin American history you will want to understand the role of formal and informal empires elsewhere. Post-colonial theories in South Asia can illuminate the work of a student of, say, Irish history. And so forth. 2 You will also write a substantial seminar paper, due on 10 May. I want it to be useful to your work, not a mere independent exercise to filled up, filed, and forgotten. The sources for world history are of course those for any particular history, though viewed as it were from above. For example, documents on the price of wheat in Venice are obviously relevant to the history of La Serenissima herself, but are even more valuable when put into world context, as for example by comparison with prices in Poland, the granary of early-modern Europe. Business correspondence that might illuminate the history of International Harvester might when compared with similar correspondence in Mexico also serve to show how bourgeois virtues made markets, or how aristocratic ethics undermined them. The seminar paper should reflect on how to do world history. It may be a review of the literature, or some part of it, as an input into a course you might teach later. Or it can be a chapter of your dissertation placing your monographic work in world context. The key requirement is that you go well beyond our preliminary bibliographies here (that is, the required readings and the bibliographies in my trilogy), and show whether or why a worldhistorical dimension aids in understanding the past. In the paper, I say: Do scientific history. As R. G. Collingwood famously put it, “Scissors-and-paste historians study periods. They collect all the extant testimony about a certain limited group of events, and hope in vain that something will come of it. Scientific historians study problems: they ask questions, and if they are good historians they ask questions which they see their way to answering” (Collingwood, The Idea of History, 1946, p. 281). The first, orientation meeting is in Lincoln Hall 201. At the second meeting and afterwards we’ll meet at my apartment, 720 South Dearborn Street, Unit 206, the code for entry to the building being *00040. Please arrive on or before time, so as not to disturb the discussion. We’ll eat bread and soup, provided. Every L line runs through my neighborhood (LaSalle on Blue, Harrison on Red, the Library stop on all the others) and many buses. Street parking is ample, though not cheap. 14 Jan, Tuesday at 5:00 pm. First, introductory meeting at Lincoln Hall 201. Introductions all around. Discussion of our mutual interests and what the seminar can accomplish. Procedures. Tentative thoughts on who does what by way of position papers. 22 Jan, Tuesday. Meet at my house. Discussion of McCloskey, The Bourgeois Virtues 29 Jan Discussion of McCloskey, Bourgeois Dignity 5 Feb Discussion of McCloskey, manuscript, The Treasured Bourgeoisie Dears, 3 It took me half an hour to get this far! I hate Blackboard. But, OK, stop whining, Deirdre. Here's the line-up (everyone should of course try to read as deeply as they can into every book, and write on it and on our discussion resulting; but the people named have the chief rapporteur/euse duty): 5 Feb, The Treasured Bourgeoisie Matt Moraghan 19 Feb, Joel Mokyr, The Enlightened Economy: An Economic History of Britain 1700–1850 (2011). Nathan Shepard 26 Feb, Janet L. Abu-Lughod, Before European Hegemony: The World System A.D. 1250-1350. (1991). Sarah Manandhar 5 March, Charles Tilly, Coercion, Capital, and European States, 990-1992 (1990). David Bleeden 12 March, Jean-Laurent Rosenthal and R. Bin Wong, Before and Beyond Divergence: The Politics of Economic Change in China and Europe (2011). Jason Archer 19 March, Jared Diamond, Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies (1997). Heather Doble 2 April, Immanuel Wallerstein, Historical Capitalism (1983). Jen Phyllis 9 April, Douglass C. North, John Joseph Wallis, Barry R. Weingast, Violence and Social Orders (2009). Aaron Finley IF YOU DON'T HAVE AN ASSIGNMENT, TELL ME PRONTO: deirdre2@uic.edu 16 Apr 23 Apr 30 Apr Exam week: seminar paper due by email to deirdre2@uic.edu at 5:00 pm 10 May. No extensions. 4