Dictionaries and Word Histories By Emmanuel Gallegos Cervantes

advertisement

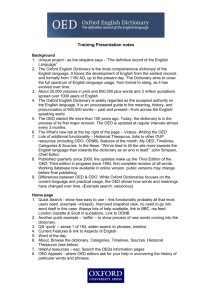

Dictionaries and Word Histories By Emmanuel Gallegos Cervantes In this chapter set of words, the politics of lexicography and judgmentalism of the modern dictionary are examined. The Oxford English Dictionary gives us insight into principles of semantic change. Linguists used to shy away from offering explanations for why particular changes took place. There are a set of principles related to semantic change drawn from recent works of linguistic theory and the history of language. The first principle involves the relationship of ambiguity and limitation: If there is a word and have two different meanings then they cause ambiguity, the form itself becomes obsolete. Homonymy and polysemy are subheadings in this category. Homonymy relates to the idea that speakers will try to avoid confusion and ambiguity in spoken language by limiting the number of possible homonyms. An example is found in the f Old English words: a (“ever”), ae (“law”), aeg (“egg”), ea (“water”), eoh (“horse”), ieg (“island”). The similarities in pronunciation of these words may have been so great that new words were borrowed or existing words were adapted to avoid homonymy. Polysemy is the phenomenon of one word having several meanings, An example is the word uncouth, the history of which we can chart with information from the OED. The word couth comes from a Germanic root meaning “known.” Another way in which words change their meaning is through extension in lexis, in which metaphorical meanings or figurative senses take over from older technical or literal meanings. These new figurative meanings constitute a problem in semantic change. Words can also experience shifts in class; in other words, meanings and usages might not change, but class affiliations or registers of meaning might. In the 18th century, ain’t was used by polite society, frequently in the form of ant; the OED considers ain’t a “later and more illiterate form of ant.” Yet the word survived in the mouth of Lord Peter Whimsey in the Dorothy Sayers novels of the 1920s and 1930s, even though Dickens, writing in the 1860s, used it as a “low” dialect word. When we look at a definition in a dictionary, we are looking at a narrative. The makers of the OED borrowed the idea that words told stories from German philologists and dictionary makers of the 19th century. In addition to giving us a sequence in linear form of historical word use and word change, dictionaries also frequently offer narratives of how words came into the language. We will attend a specific word as an example of the historical narratives. 1. The word cheap is a story of extension-in-lexis more than 2,000 years old, from the Germanic languages into English. The word is a product of the period of continental borrowing, the time before the Germanic tribes (and languages) split up, when many words for commerce, warfare, architecture, and social control were borrowed from Latin. 2. All the modern Germanic languages have a word that comes from the Latin caupo, meaning “small merchant.” In Modern German, kaufen is a verb meaning “to buy and sell”; a Kaufmann is a “merchant.” The name of the city Copenhagen can be traced back to an older Norse word that meant “merchant’s harbor or haven.” 3. In Old and Middle English, the word cheap underwent extension-in-lexis to refer to the thing bought or sold, the quality of the purchase. The result was such idioms as good cheap, meaning a good buy, and dear cheap, a seeming oxymoron meaning something scarce and expensive. 4. Throughout London, there still exist place names and street names, such as Cheapside, that refer to market areas. As we saw in Shakespeare’s Sonnet 87, the language of commercial exchange could also be applied to a love relationship. 5. In the 17th century, the word cheap took on its modern sense, that is, something that is inexpensive or easy to obtain and, thus, likely to be of low quality. 6. What we see in this narrative history of the extension-in-lexis of cheap is a history of the economy of the British Isles and the relationship between scarcity and value that came to control the market and credit economy. The words protocol, diploma, and collate also illustrate changes in meaning from the specific to the general and pose problems for the lexicographer. These three words all ultimately relate to pieces of paper. Diploma means “to fold over.” A diploma is, quite simply, a folded piece of paper. b. In Medieval Latin, a diploma was a charter or a document; diplomacy became the practice of conducting state business through folded pieces of paper. c. It was not until the early 18th century that the word diploma was first used to refer to the documentation associated with a university degree. d. In this word, we see the transference of meaning from textual to political phenomena, that is, from the material of organization to the behavior surrounding that material. 2. The word collate comes from Latin and means simply “to compare or confer.” In the 17th century, it acquired the meaning of bringing texts together to make certain kinds of comparisons. 3. In Greek, the colophon is similar to a title page, on which the scribe wrote his name and information about the document. The proto-colophon was what came before the colophon, the first sheet of a manuscript. From this, we get the word protocol, which like diplomacy, relates to the business of paper. Even today, the OED maintains the judgmental 19th-century definitions of protocol as a word that was not fully part of the English vocabulary.