Tyler African_Settlements_and_Geometric_Fractals

advertisement

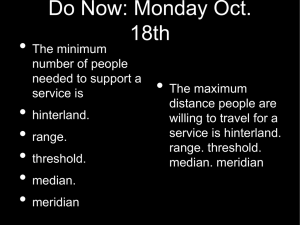

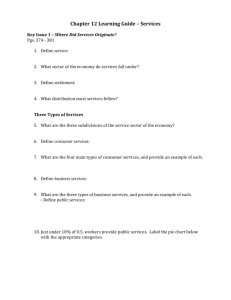

‘African Settlements and Geometric Fractals’ Tyler Carrara March 26th, 2014 RIN: 661181672 ‘African Settlements and Geometric Fractals’ African societies have been observed applying fractal geometry in various areas of cultural significance; one area being African settlements implementing rectangular or circular fractal geometry for defensive, social, spiritual, and agricultural reasons. The fractal based culture of certain African societies contrasts sharply with the established concentric and Euclidean cultures of the Native American and South Pacific societies respectively. The differences become clearly evident when examining the architectural designs produced by each culture, specifically with regard to settlement layouts. While fractals appear in many different facets of African culture, their levels of implicit intent—conscious implementation—have the potential to vary drastically. Unintentional implementation of fractal geometry occurs when fractals are the unintentional by-product from some other purpose. Conscious implementation can be determined through evaluating the construction techniques and knowledge systems of the culture. Several other theoretical frameworks exist through which African fractals can be evaluated, with some extreme theories suggesting that all cultural fractals can be dismissed as unconscious creations. While African societies’ conscious incorporation of fractals into their own settlements may be controversial, what remains undisputed is the existence of fractals within the African settlements. While “not all architecture in Africa is fractal” (Eglash 20), African settlements consistently integrate fractal geometry “among such a wide variety of shapes” (Page 20). The Kotoko peoples’ rectangular fractal architecture relies on iterations of self-similar scaling, “it makes use of the same pattern at several different scales” (Page 21). The underlying reasons behind this architectural design are founded on the historic need for defense as “in the past, invasions by northern marauders were common, and so a larger defensive wall was also needed” (Page 21). Another, less obvious, reason is the integrity of family ties is sustained and preserved by having sons build off of their father’s homes “by adding walls to the father’s house” (Page 21.) The Bamileke contain a fractal settlement architecture based on rectangles as well; although no cultural relation exists between the Bamileke and the Kotoko people. Instead of thick clay, the houses and the attached enclosures are crafted with bamboo. For the Bamileke people, bamboo is readily available and is exceedingly strong. The Bamileke society’s settlement layout is greatly influenced by agricultural production rather than “kinship, defense, or politics… the grassland soil and climate are excellent for farming, and the gardens near the Bamileke houses typically grow a dozen different plants all in a single space” (Page 24). Both the Kotoko and Bamileke people employed rectangular fractal architectures with distinct methods of construction and aspects of their own cultural history in mind, pointing to conscious implementation. While the Kotoko and Bamileke people demonstrate use of rectangular fractals, a Ba-ila settlement exhibits clear signs of circular fractal incorporation. The layout is such that: Toward the back of each pen we find the family living quarters, and toward the front is the gated entrance for letting livestock in and out. For this reason the front entrance is associated with low status (unclean, animals), and the back end with high status (clean, people). Page 26 While this gradient of status exists among the minds of the society’s members, the architecture reflects this gradient with the front being composed of only fencing, the middle of storage enclosures, and toward the very back end larger houses. The physical ring shape and status gradient of the settlement represent two geometric elements that echo “throughout every scale of the Ba-ila settlement” (Page 26). Inside and toward the back of the settlement’s exterior ring is the “chief’s extended family. Inside and toward the back of the chief’s extended family ring, the chief has his own house… it is a ring with a special place that the back of the interior: the household altar” (Page 26). The placement of the household altar implies that spiritual practices influenced the layout of the settlement—a fractal’s recursion can be interpreted as symbolic. The Mofou settlements express characteristics of circular fractals as well. The architectural structure of the settlement mimics a spiral that upon later iterations contains clusters of granaries within smaller, replicated spirals that “whorl about a central location. The spiral dynamic can be missed with just a static view” (Page 29). The Mofou settlement’s layout is dependent on a “precise knowledge of agricultural yield. This volume measure was then converted to a number of granaries, and these were arranged in spirals” (Page 31). Circular architectures in Africa did not all contain a centralized location—as was witnessed in Mokoulek. The Songhai village of Labbezanga in Mali exhibits “circular swirls of circular houses without any single focus. But… we see that a lack of central focus does not mean a lack of selfsimilarity” (Page 31). The self-similar scaling associated with circular fractals is “far from unconscious accident… they have made conscious use of the scaling in their social symbolism” (Page 34). Both the Ba-ila and Mofou people have demonstrated conscious reasoning behind the decision to implement circular fractal architecture into their settlements. African settlements comprised of circular clusters usually contain paths that are typically not circular. The paths can be compared that to that of “bronchial passages that oxygenate the round alveoli of the lungs, the routes that nourish circular settlements often take a branching form” (Page 34). Such settlements are the product of conscious design as each settlement’s society can choose “either to maintain or erase the branching forms. Discussion concerning such decisions are apparent in the settlement of Banyo, Cameroon” (Page 34). The transition in Banyo, Cameroon extends well into the past where rectangular buildings eventually became favored over circular buildings. The few circular buildings presently left serve as an embodiment of cultural memory. The structure of the transportation paths in Banyo, Cameroon resemble that of the veins found within a leaf—a branching fractal structure. The city of Cairo, Egypt has branching fractals as well. The street branching in Cairo, Egypt is derived from a seed shape that “consists of a mosque connected by a wide avenue to the marketplace, and successive iterations of construction add successive contractions of this form” (Page 38). Paths that mimic branching fractals are clearly advantageous when examining the flow of traffic and resources. If this style of design had not been consciously implemented, paths would have ended up being more irregular with regard to width, length, and direction when examining specific portions of Cairo, Egypt. The fractal architecture associated with African settlements contrasts greatly with Native American indigenous settlements. From an aerial vantage point, Native American settlements appear to be composed of rectangular buildings that revolve around a center point forming an “enormous circular form…certainly not the same shape at two different scales. The juxtaposition of the circle and the quadrilateral form is not a coincidence; the two forms are the most important design themes in the material culture of many Native American societies” (Page 40). No known examples of nonlinear scaling exist within Native American villages; however, nonlinear scaling is observed in African settlements: The only Native American architectures that come close are a few instances of linear concentric figures. Shapes approximating concentric circles can be seen in the Poverty Point complex in Northern Louisiana, for example, and there were concentric circles of tepees in the Cheyenne camps. Page 40-41 Linear concentric figures are not fractals; rather, linear concentric figures contain linear layers. This means that the number of concentric circles within the outer-most circle is finite. Nonlinear scaling differs from fractals as fractals “require an ever-changing distance between lines” (Page 41). While Native American settlements lack the incorporation of fractal geometry and instead employ linear concentric figures, the Native American settlements are no less complex than African settlements; Native American settlements simply cater to the desires of a fundamentally different culture. The South Pacific culture is just as unique as the Native American culture, differing from the African settlements as well. Indigenous populations in the South Pacific incorporate Euclidean architectures within their settlements that contrast sharply with African and Native American villages. Building construction is a combination of “rectangular grids with triangular or curved arch roofs. Occasionally these triangular faces are decorated with triangles, but otherwise nonscaling designs dominate both structural and decorative patterns” (Page 47). While both the Native American and South Pacific settlements lack fractal geometry, no implication can be made that either settlement lacks “sophistication in their mathematical thinking” (Page 47). If fractal geometry had originated in African settlements due to “nonstate social organization, then we should see fractal settlement patterns in the indigenous societies of many parts of the world” (Page 39). Since the examples mentioned above demonstrate that this is not the case, a conclusion can be drawn that the implementation of fractal geometry into African settlements is intentional. After examining the facets of other indigenous cultures, it is apparent that societies frequently incorporate different mathematical methods for designing the layout of their settlements. African settlements have been seen to implement complex fractal geometry while Native American and South Pacific societies employ the simplicity of linear concentric figures and Euclidean geometries respectively. The unique culture of African Societies necessitate the implementation of specific construction techniques, therefore these fractal designs that were ultimately selected are not a product of (random choices); they have been intentionally designed and selected to suit the parameters of African society. This logic transitively verifies that Native American and South Pacific societies consciously implemented linear concentric figures and Euclidean geometries into their settlements respectively. African societies’ conscious incorporation of fractals into their own settlements has proven that unique cultural factors greatly affect the physicality of the settlement. Well written, very nice reflection. One minor point: “Since the examples mentioned above demonstrate that this is not the case, a conclusion can be drawn that the implementation of fractal geometry into African settlements is intentional.” It’s a little more complicated: it shows something culturally specific—which implies some level of consciousness. That has to interact with intentionality, but how it interacts is another set of questions. Grade = A. Citations: Eglash, Ron. African Fractals: Modern Computing and Indigenous Design. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers UP, 1999. Print.