Word 07 - Clark College

advertisement

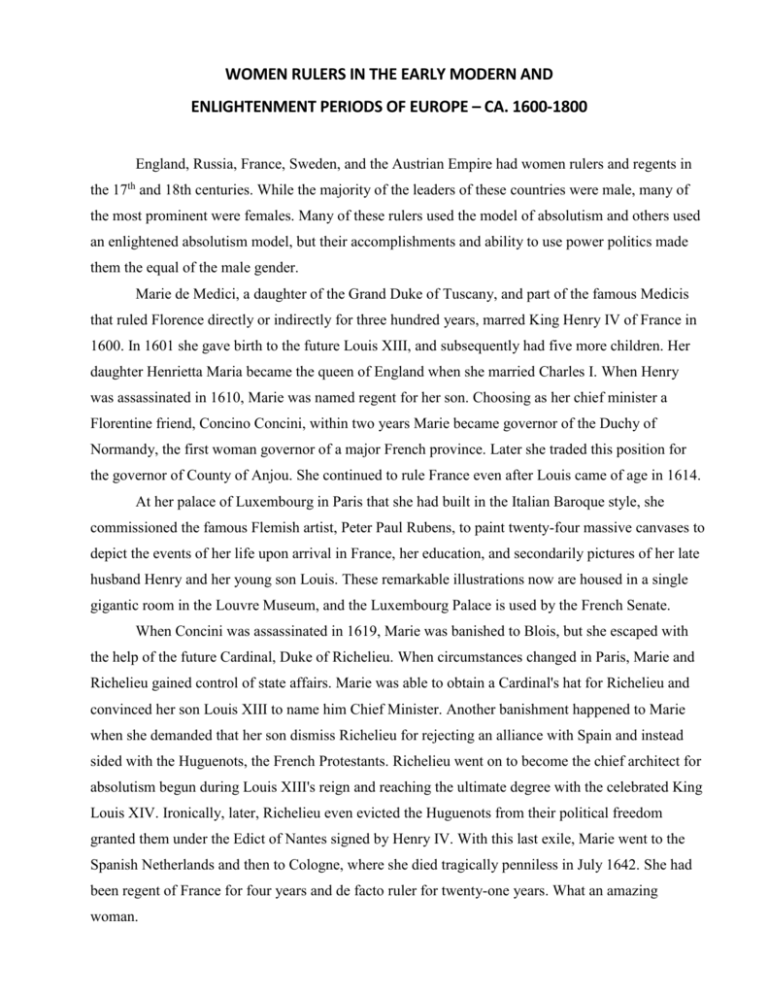

WOMEN RULERS IN THE EARLY MODERN AND ENLIGHTENMENT PERIODS OF EUROPE – CA. 1600-1800 England, Russia, France, Sweden, and the Austrian Empire had women rulers and regents in the 17th and 18th centuries. While the majority of the leaders of these countries were male, many of the most prominent were females. Many of these rulers used the model of absolutism and others used an enlightened absolutism model, but their accomplishments and ability to use power politics made them the equal of the male gender. Marie de Medici, a daughter of the Grand Duke of Tuscany, and part of the famous Medicis that ruled Florence directly or indirectly for three hundred years, marred King Henry IV of France in 1600. In 1601 she gave birth to the future Louis XIII, and subsequently had five more children. Her daughter Henrietta Maria became the queen of England when she married Charles I. When Henry was assassinated in 1610, Marie was named regent for her son. Choosing as her chief minister a Florentine friend, Concino Concini, within two years Marie became governor of the Duchy of Normandy, the first woman governor of a major French province. Later she traded this position for the governor of County of Anjou. She continued to rule France even after Louis came of age in 1614. At her palace of Luxembourg in Paris that she had built in the Italian Baroque style, she commissioned the famous Flemish artist, Peter Paul Rubens, to paint twenty-four massive canvases to depict the events of her life upon arrival in France, her education, and secondarily pictures of her late husband Henry and her young son Louis. These remarkable illustrations now are housed in a single gigantic room in the Louvre Museum, and the Luxembourg Palace is used by the French Senate. When Concini was assassinated in 1619, Marie was banished to Blois, but she escaped with the help of the future Cardinal, Duke of Richelieu. When circumstances changed in Paris, Marie and Richelieu gained control of state affairs. Marie was able to obtain a Cardinal's hat for Richelieu and convinced her son Louis XIII to name him Chief Minister. Another banishment happened to Marie when she demanded that her son dismiss Richelieu for rejecting an alliance with Spain and instead sided with the Huguenots, the French Protestants. Richelieu went on to become the chief architect for absolutism begun during Louis XIII's reign and reaching the ultimate degree with the celebrated King Louis XIV. Ironically, later, Richelieu even evicted the Huguenots from their political freedom granted them under the Edict of Nantes signed by Henry IV. With this last exile, Marie went to the Spanish Netherlands and then to Cologne, where she died tragically penniless in July 1642. She had been regent of France for four years and de facto ruler for twenty-one years. What an amazing woman. The next enlightened ruler was Queen Christina, who ruled Sweden in the seventeenth century. She inherited the throne when she was not yet six when her father, Gustavus Adolphus II, died. Christina wrote in her memoirs: "I was born covered with hair from head to knee; only While she was the de jure monarch from 1626-1654, she was only both the de jure and de facto ruler for ten years my face, arms and calves were hairless. I was all fuzzy. I had a deep and strong voice. All this made the women who received me think that I was a boy." To this comment by the women, her father replied: "I hope this girl will be worth a boy to me...she will be clever, since she has followed us all." Clever she was, and her father Gustavus raised her like a prince. She learned to ride like a boy, straddling the horse, not side-saddle like ladies riding a horse. On Saturdays she was taught and played various sports like fencing and target shooting. As an adult woman she loved to dress like a man. Christina was given an education of a prince, where she devoted six hours each morning to her studies, and in the afternoons she learned many foreign languages. Having a super intellect, at the age of twelve she began to occupy herself with affairs of state, and by the time she was fifteen, she started to receive ambassadors from other nations. The following year she participated in the Regency Council, and at the age of eighteen, she took over the complete reins of power. As queen she took her public duties very seriously, and she became a shrewd politician. The Renaissance came to Sweden in her reign, and it was co-mingled with the increasing interest in science and philosophy. Gathering around her the greatest minds of the seventeenth century Europe, including the French philosopher, Rene Descartes, Christina made her country of Sweden into a real empire, that dominated the Baltics and included part of the Germanies. She was able to extricate Sweden from the exhausting Thirty Years' War, reformed the country's educational system, and oversaw the revival of classics in her native country. Just like Elizabeth I of England, Christina never married and rejected all suitors, not wanting to lose her independence and share her power. However, after ten years of ruling Sweden in her own right, she abdicated, citing public complaints and the burden of ruling. Her cousin became king, Charles X. She chose to leave Sweden and travel throughout Europe. The following year she publicly converted to Catholicism, that she had secretly converted to earlier. As the Catholic faith was not allowed in Sweden because they had converted to Lutherism in the sixteenth century, it is thought this was the main reason she abdicated. The Pope in Rome at the time called her a "woman born a barbarian, barbarically raised, and living with barbaric ideas." Taking up residency in Rome, Christina lived at the Farnese Palace, where she gave splendid receptions. Perhaps this is where she met Cardinal Decio Azzolino, who she tried to get elected pope. Apparently they had great love for each other that lasted twenty-five years. While in Rome for two 2 years, Roman society did not welcome her wholeheartedly as she claimed the same honors and protocol as the Pope. Soon Christina started searching for another crown. She was promised the crown of Naples as well as the ruler ship of Poland, both Catholic countries, but she did not obtain them. Failing in these attempts to secure a crown, she renounced the world in 1688 when she wrote: "Leave me in oblivion and obscurity. Do not try to draw me out." Ironically, practically the same remarks that the famous actress, Greta Garbo, will make in the twentieth century. Greta in the 1930's even played Queen Christina of Sweden. In 1689 Christina died, one year after Mary II became queen of England, following the Glorious Revolution of 1688 when the English Parliament banned King James II, and invited Mary (his daughter) and her husband William of Orange to jointly rule England. The sister of Mary II, Anne, became queen of England (1702-1714), when Mary and William did not leave any heirs. In 1701, the Act of Settlement declared that after Mary would come princess Anne, then Princess Sophia. Sophia was the Electress and Dowager Duchess of Hanover in Germany, and daughter of Elizabeth, the late Queen of Bohemia, who was the daughter of James I, the first Stuart monarch in England. It was Sophia's son, George, who became King George I of England, when Anne died without heirs in 1714. Anne was born in 1665. As the likelihood of her succeeding to the throne appeared to be remote when she was young, she was uneducated and untrained for a monarchical position. Anne was married to Prince George of Denmark. Tragically, she led an unhappy life for the most part. While having seventeen children, the only one that lived past infancy was William, Duke of Gloucester, a hydrocephalic who lived for only eleven years. By the time she was queen, she was in constant pain. Modern doctors are not in agreement about the diagnosis of her illnesses, but apparently Anne's contemporaries called it gout. As she grew older she became exceedingly stout, and she often had to be moved on chairs or by pulleys. She was an extremely conscientious Queen, and was a strong pillar of the Church of England. She endowed out of her private funds resources for poor clergy, and gave 10,000 pounds to the noted writer and feminist Mary Astell to start the first women's college in England. While that did not happen, her name was respected among churchmen long after her death. During her reign England and Scotland came together as Great Britain, and the Parliamentary elections and party contests became genuinely significant. Architecture and furniture of her reign came to be called the Queen Anne style, and examples of this are world-wide. In Russia there were two remarkable Tsarinas, Elizaveta (English Elizabeth) Petrovna (17411761) and Ekaterina Alexeevna (Catherine the Great II) (1762-1796). Elizaveta was the second daughter of Peter the Great and his wife, Catherine I of Russia. Peter was perhaps the most significant 3 ruler in Russian history. During Peter's reign he started the westernization process of Russia that Elizaveta and Catherine continued. Moving the capital from Moscow, Peter established the new one, St. Petersburg, on the Baltic Sea on land taken from Sweden. Kept in political obscurity for more than thirty years, in traditional Russian style, Elizaveta was able to forcefully grab the crown in a military coup in 1741 at the age of thirty-three. During her reign, Elizaveta made significant advances in both the economy and the culture. In foreign policy Russia became so important that all the other states were eager to make treaties with her. One of Elizaveta's most important decrees was the abolition of capital punishment in 1744, and during her reign not a single person was executed. The first university in Russia, Moscow University, was founded by her in 1755. Two years later she established the Academy of Fine Arts, and hired the Italian Baroque architect, Bartolomeo Rastrelli, to erect a number of "Baroque projects" including the Winter Palace, Smolny Cathedral, the Summer Palace, St. Andrew's Cathedral in Kiev, and many more. Loving to dance, it was reported that she never wore the same extravagant gown twice. Although she spent an untold amount of money with her lavish lifestyle and building projects, she was popular in Russia for keeping the Germans out of the government. Having no heir, she instigated the marriage of her nephew Peter with the German princess, Sophia, the future Catherine the Great. She is buried in St. Peter and St. Paul Cathedral where most of the Romanov monarchs are interred. When Elizabeth died, her nephew Peter became the Tsar. By this time Sophia von AnhaltZerbst had been the wife of Peter for seventeen years. During this time, Sophia used it wisely by Russifying herself. Educating herself in politics through voluminous reading and shrewd observations of court intrigues. From the earliest time in Russia, Sophia studied the Russian language, she even converted from Lutherism to the Russian Orthodox faith, and received the name of Catherine. Reading was highly unusual especially for Russian women, as barely half the entire population could read and only one-third could write. Not only reading and learning about the historical and political events, Catherine read widely the writers of the Enlightenment such as Montesquieu, and especially Voltaire. When Catherine's husband became Tsar in 1762, she immediately began plotting his downfall, and in a similar fashion to the coup carried out by Elizabeth, she led the palace guards in a revolt against her husband Peter III. Peter was forced to abdicate after Catherine was crowned by her own hands at the Cathedral of Kazan, just like Napoleon will do later in France. She took the oath as Empress and Sole Autocrat. Six days later apparently Alexis Orlov confessed to her that he had 4 murdered her husband. Frederick the Great, the ruler of Prussia, remarked on news of Peter III's overthrow said: "He let himself be driven from the throne as a child is sent to bed." Catherine was involved with a number of male favorites referred to as her house pets. At first her affairs were clandestine, but she soon displayed her lovers as French kings paraded their mistresses. Once a young man was chosen, she showered him with expensive gifts. When Catherine tired of him he was given a lavish going away present such as land (that she had taken from others in Russia or by conquest of foreign lands.) Catherine, like most other enlightened despots or absolute monarchs, always thought of herself as a superior being. Kind and considerate to her servants and other commoners, she never lost awareness of her rank. In Russia as elsewhere, paternalism not egalitarianism was the keystone of benevolent despotism. In another one of Frederick the Great's witty aphorisms, he said that “if Catherine corresponded with God, she would probably claim equal rank." During her reign the Russian people were dazzled by Catherine's political skill and conduct of complex diplomacy. Unfortunately, she did not continue her predecessor's ban on capital punishment, and many potential enemies were executed even before they had a chance to rebel. She also continued the economic reform and westernization of Russia of her two predecessors. During her reign schools and universities were established all over the Russian Empire, including naval and military cadet schools, medical and agricultural schools. Her foundation of Smolny Institute for Girls was perhaps her most remarkable. She modeled it after Madame de Maintenon's famous Institute of Saint Cyr, and was the first serious attempt to improve female education in Russia. Catherine herself supervised the curriculum, and it was still flourishing when the Russian Revolution occurred in 1917. Lack of teachers drove Catherine to send promising young men to Europe to become educated at her expense. Not sparing her army, she continued the Russian policy of fighting the Turks for a Black Sea port. Success was hers and Russian control of an outlet on the Bosphorus in the Crimea occurred. Orchestrating the carving up of Poland, Catherine took approximately one-third of it, Prussia a third, and the Austrian Empire the last one-third. These great powers contended they were saving themselves and the rest of Europe from Polish anarchy. Lithuania also became one of her conquests. Influenced by the French Philosoph, Montesquieu, Catherine drew up a new law code for Russia, and she formed a commission of representatives from all classes except serfs to discuss government reform. Neither project led to real change, but they did make Catherine celebrated in Western Europe, and greatly increased the prestige of the Russian monarchy. With guidance from Voltaire, Catherine began making plans to slowly release the bonds of serfdom, but a rebellion 5 purported to be lead by her dead husband Peter III, stopped this freedom for the peasants. A renegade Cossack soldier named Pugachev, claiming to be her long-lost husband, who was determined to dethrone Catherine and place their son Paul on the throne. For a time the Rebellion appeared to be winning as Russia's main army was at war with the Turks, but Pugachev was betrayed, ending the rebellion. Consequently, Catherine felt the need to halt her emancipation of the serfs, and placed even more onerous binds on them. Serfs could not be bought and sold, and serfdom was extended into new areas. Once the French Revolution broke out in 1789, Enlightenment books were censored, and any offensive Russian authors were sent into Siberian exile. This was the beginnings of the notorious Siberian exile system that Stalin later used to his terrible discredit. Catherine now recognized that she needed the ruling class's complete cooperation to maintain her power, and in 1785 she freed the boyars or aristocrats forever from taxes and state service. Catherine's fame and notoriety grew throughout her long reign. Now that the USSR is no longer, Catherine's place in Russian History is gaining positive reviews. Marie Theresa of Austria was another famous woman ruler in the 18th century. Living from 1711-1780, she ruled as Holy Roman Empress, Queen of Hungary, of Bohemia, of Dalmatia, of Croatia, of Slavonia, Archduchess of Austria; Duchess of Burgundy, etc. from 1734-1765, and then jointly with her son Joseph II from 1765-1780. Her rise to becoming a powerful ruler is astonishing, for she inherited the crown at the age of twenty-three completely untrained. There was no adult male heir to succeed her father Charles VI, and only the weakest precedent for a female ruler, so Charles sought approval of his family and foreign powers to accept Maria as his heir. These European powers signed the document called the Pragmatic Sanction, theoretically approving Marie's succession. When Charles died and Maria came to the throne, the Austrian Empire was in dire circumstances. It was nearly bankrupt because of Charles' lavish spending. Lacking an army, and virtually no central administration and sensible advisers, Austria was in need of a competent ruler. All Maria really had going for her was her youth, her beauty, and her strength of character. She had been allowed to marry for love when her first fiancé died when she was five. Maria always thought that the Hapsburgs had not fared well because of lack of sons, and therefore she and Francis Stephen, her husband, had sixteen children, five boys and eleven girls. Her daughters all had the first name of Marie for Mary, the mother of Jesus, including her youngest daughter Marie Antoinette, the wife to Louis XVI of France. France, Spain and Prussia were all secretly planning to dismember the Austrian Empire, even though pledging otherwise by signing the Pragmatic Sanction. Frederick the Great, Prussia's ruler, struck first by grabbing the rich agricultural and mineral region of Silesia. Attempts throughout Marie Theresa’s rule were to no avail in gaining back this 6 area. Then France and the Bavarians were next in line to conquer parts of the Austrian Empire. Even Marie-Theresa's capital city of Vienna was threatened. Over the course of her reign she would go from pleading with her advisers and generals to ordering them to do her bidding regarding war and matters of state. Although she was involved in a series of wars to defend her kingdom, Marie Theresa was on the defensive and never on the offensive. She ruled as the Archduchess of Austria, and queen of Bohemia and Hungary. Her husband was the Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire and she was the empress, but in reality her husband Francis did not wield any power. He was made Emperor to satisfy people’s anti-female leadership. Marie Theresa's accomplishments in the cultural and political realm were numerous. She convinced the non-German provinces to accept the hegemony of German officials and the German language. By the time she died, she had provided Austria with the following: a standing army, councilors of state, a system of education even on the primary level, competent civil service, all the while being the mother of sixteen children. By strengthening the central government at the expense of the local aristocratic assemblies, she was able to accomplish what Louis XIV of France did, but with an enlightened absolute model. Concerned with the welfare of the peasants and serfs, she issued decrees limiting the amount of labor or robot that could be demanded from the peasantry by the landowners. Culturally, she was a major patron of the composer and child prodigy Mozart. At the age of fifty-four, Marie Theresa allowed her son, Joseph II, to co-rule with her for the next fifteen years. Upon her death in 1780, Joseph became too much of a reformer, and destroyed in his ten years of rule, much of Marie Theresa's skillful statecraft. He abolished serfdom and proclaimed religious toleration, progressive policies that were not accomplished in Europe until the twentieth century, but his successor moved the Austrian Empire back to a more workable format that was operative during Marie Theresa’s rule. 7