Pathway-RobinHoodMyth - ACU Blogs

advertisement

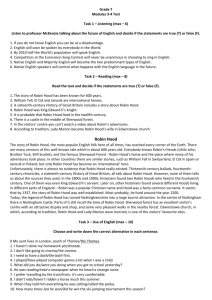

ABILENE CHRISTIAN UNIVERSITY THE FUNCTION OF ROBIN HOOD AS MYTH IN WESTERN CINEMA SUBMITTED TO DR. JONATHAN HUDDLESTON IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF BIBL 640 BY M. BARRETT DAVIS 28 MARCH 2012 THE FUNCTION OF ROBIN HOOD AS MYTH IN WESTERN CINEMA “Classical myths have come down to us from multiple sources, in part because they are so often alluded to by poets, essayists, and orators, meaning that the act of retelling is central to the production and continued relevance of mythology.”1 In the many retellings of the tale in the realm of modern Western cinema, Robin Hood has traditionally paid homage to gender and authority stereotypes in Western society, with significant reinterpretations born out of the major social movements through the 20th century. This fluidity gives greater strength and broader function of the Robin Hood mythos. Utilizing its underlying power, then, Robin Hood has acted as a myth in the culture of the West because of the myriad forms that its interplay between civilization & nature, law & virtue, and gender roles, among others, takes in its various retellings as both perpetuator and critic of society. Analysis of this myth will also provide an effective point of reflection for churches in the West to study their own beliefs about gender roles, power structures, justice and equality, as will be shown in applying it to the Northside at the Crossroads case study. A group of long-time members has pushed back against changes in the Northside Church of Christ, and they have portrayed the authority of the new minister John as an oppressive force threatening their traditional order, values, and identity.2 1 Michael Marek, “Firefly: So Pretty It Could Not Die,” Sith, Slayers, Stargates, and Cyborgs: Modern Mythology in the New Millennium (New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 2008), 117. 2 Tim Sensing, “Northside at the Crossroads.” [cited 28 March 2012] http://blogs.acu.edu/gstpathways/cases/northside-at-the-crossroads. I. The Robin Hood Myth The earliest mention of Robin Hood in literature dates back to 1377. Much of the early literature depicts Robin as a chaotic force continuously provoking established social structures and, in the end, being beaten down.3 Following the retellings of the Robin Hood mythos through Western cinema, we will observe a very different Robin as he adventures in the midst of changing power dynamics between men and women and between traditional authority and common morality and justice. The 1922 silent film Robin Hood actually resembles the ancient Robin, but he does so as an Earl of the established social order, expressing his chaotic nature in relationship to all women, going so far as to admit, “I am afeared of women.”4 King Richard acts as the voice for social normalcy by continually telling Robin to take a maid for himself, and only at the end of the movie does Robin marry Marian. However, even as the two walk into their bedchamber, they are depicted as “a mother with child at her knee,”5 and Robin remains as a boy who is hesitant to become a man in relation to his female counterpart. In this same movie Marian is shown as a chaste woman, who has no agency throughout the events of the movie and no purpose but to charm Robin into marriage. Assuming Geoffrey Gates’ analysis that retellings often restrict the outlines of the story and 3 Richard Stapleford, “Robin Hood and the Contemporary Idea of the Hero,” Literature Film Quarterly 8 no. 3 (1980), 184. As the story was re-told through England over many generations and Robin Hood began to be accepted as an English icon, the General Assembly even tried to have the ballads about him banned as they might incite disorder among the peasantry. 4 Lorraine K. Stock and Candace Gregory-Abbott, “The ‘Other’ Women of Sherwood: The Contstruction of Difference and Gender in Cinematic Treatments of the Robin Hood Legend,” Race, Class, and Gender in “Medieval” Cinema eds. Lynn T. Ramey and Tyson Pugh, (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007), 200. 5 Ibid., 201. its values to established, conservative ideology,6 this would seem to support that the most prevalent ideas about gender roles in the early 20th century valued a woman’s marriage to a husband and her chastity above agency in either social or political realms. Also, Marian’s servant offers an interesting point of contrast to Marian. This woman of the lower class is often vocal, always sexualized, and seems to carry the social authority among her peers in the many Robin Hood narratives, where Marian as the highly civilized and ideal woman for the protagonist possesses none of these traits.7 This pattern of agency persists in portrayals of Marian until the movies and television series made after World War II. 8 After the war in which men went overseas and women entered into the economy, the factories, and the business offices, we see a Marian as well as a Queen Eleanor who are the representatives of King Richard’s power while he is away at the Crusades, defending it from the chaotic and evil forces that would usurp it.9 Later in the 1976 Robin and Marian, born in the midst of the feminist movement, Marian is given her own agency and freedom to choose her purpose as she has become a nun and often chides an aging Robin (played by an aging Sean Connery) for acting as a child in his attempts to chivalrously defend her—in fact, Marian eventually murders Robin, an overt attempt to declare that this old icon of traditional roles and power structure no longer has a place in society.10 The most iconic Robin Hood story of the 20th century is the 1938 film The Adventures of Robin Hood starring Errol Flynn, and this Robin has remained the template by which other Robins are interpreted in the air of the dominant culture. This story is the one 6 Geoffrey Gates, “‘Always the Outlaw’: The Potential for Subversion of the Metanarrative in Retellings of Robin Hood,“ Children’s Literature in Education 37 no. 1 (March 2006): 69. 7 Stock & Gregory-Abbott, 206. 8 Ibid., 204. 9 Ibid., 205. 10 Ibid., 208. that stained the wood of Robin’s arrows with moral purpose fighting against tyrannical authorities; fitting that it was filmed in the years that Nazi Germany was invading other European countries. After the Watergate scandal of 1972 and the erosion of naïve trust in authorities, Robin was no longer depicted as a noble but as one of the peasantry, even in the most recent Robin Hood in 2010 with Russell Crowe. Crowe’s Robin, however, is adopted into nobility, and eventually speaks before the tyrannical King John on behalf of the common man. Instead of the traditional “rob (wealth) from the rich and give to the poor” Robin, this one seeks to take the absolute authority of the power-rich crown and give the power-stripped common man: “Every Englishman’s home is his castle. What we would ask, Your Majesty, is Liberty—Liberty by law.”11 This most recent Robin seeks for reconciliation between the authorities and the commoners by a sharing in power and responsibility for their kingdom. II. Robin Hood & the Church(es) at Northside. Reconciliation may be difficult to find in the Northside Church of Christ, as well as any other North American church sharing similar struggles. A group of established members at the church feels that their new ministerial authority, John, has been pursuing his own agenda for the church at the expense of the older members.12 Their accusations are partially true because John admits to focusing on inviting into Northside the growing and changing demographic of the community around the church. The changes show up in 11 Robin Hood (2010), directed by Ridley Scott, perf. Russell Crowe & Cate Blanchett (Universal Pictures, 2010). 12 Sensing. worship style, in John’s own view of his role as minister, and in the make-up of the church, all of which seem threatening to the older members’ paradigm of Northside. The Robin Hood mythos can critique the older group in its continuing message of “rob from the rich and give to the poor”—that blessing should flow from the blessed to those who have no blessing. In this case, the blessing is membership in a life-giving community of believers in Jesus Christ, and the older group wants to keep all of its blessing and not spend it upon those who do not have it. However, one study shows that the majority of Americans may not hold as much value in “giving to the poor” as they might admit. When given a chance to take what amounts to a free gift of money to save the lives of starving people, most participants in this study would not take the money because they gave higher importance to the idea of that money being another’s property then of saving a human life: “Overall, subjects tended to prefer the inactive option, and that choice was correlated with property preserving, not altruistic ethics.”13 This may give insight into the older members’ motivation—they feel like what is “their church” is being taken from them and would prefer to keep what belongs to them instead of losing it as a source of their identity. Also, as a warning to the leaders of the church, Graham Seal’s “Robin Hood Principle” states that anytime a group feels oppressed, a narrative championing their cause will grow and create more tension between “oppressed” and “oppressor.”14 If John wishes to reconcile with this disgruntled group, he will need to work with the entire church to buy into and share responsibility for a common paradigm of the church and its mission. 13 Matthew Hirshberg, “Robin Hood Revisited: Theft, Charity, and the Ethics of Inequality,” Journal of Poverty 4 no. 3 (2000), 94. 14 Graham Seal, “The Robin Hood Principle: Folklore, History, and the Social Bandit,” Journal of Folklore Research 46 no. 1(Jan-Apr 2009), 83. Bibliography Gates, Geoffrey. “‘Always the Outlaw’: The Potential for Subversion of the Metanarrative in Retellings of Robin Hood.“ Children’s Literature in Education 37 no. 1 (March 2006): 69-79. Hirshberg, Matthew. “Robin Hood Revisited: Theft, Charity, and the Ethics of Inequality.” Journal of Poverty 4 no. 3 (2000): 73-97. Knight, Stephen. A Complete Study of the English Outlaw. Boston: Blackwell Publishing, 1994. —. “A Garland of Robin Hood Films.” Film & History 29 no. 3/4 (Sep-Dec 1999): 34-44. Ramey, Lynn T. and Tyson Pugh, eds. Race, Class, and Gender in “Medieval” Cinema. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007. Seal, Graham. “The Robin Hood Principle: Folklore, History, and the Social Bandit.” Journal of Folklore Research 46 no. 1, Jan-Apr 2009: 67-89. Sensing, Tim. “Northside at the Crossroads.” [cited 28 March 2012] http://blogs.acu.edu/gstpathways/cases/northside-at-the-crossroads. Stapleford, Richard. “Robin Hood and the Contemporary Idea of the Hero.” Literature Film Quarterly 8 no. 3, 1980: 182-187. Whitt, David and John Perlich. Sith, Slayers, Stargates, & Cyborgs: Modern Mythology in the New Millennium. New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 2008.