Colon Cancer - Emily Claire Macieiski`s Dietetic Internship Portfolio

advertisement

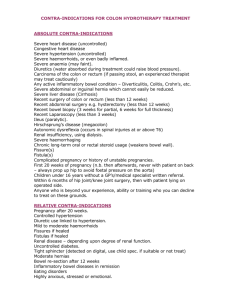

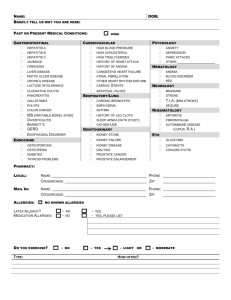

Colon Cancer A Major Case Study By: Emily Macieiski Introduction: J.W. is a 53-year-old male who was admitted to Atrium Medical Center (AMC) with anemia and abdominal pain. He also presented with an elevated HgA1c of 9.02%. His admission weight was 183 pounds, and he is 5’11”. His BMI upon admission was 26.47 kg/m2; classifying him as overweight. J.W. was admitted on February 19, 2014, and was assessed on January 21, 2014 due to the elevated HgA1c, placing him at “moderate” nutritional risk. He was discharged from AMC on February 26, 2014. J.W. was chosen for this study because of his positive outlook on life, even when things were not going well for him at the moment. Also, he has no past medical history. During his stay at AMC he was diagnosed with both type II diabetes mellitus and stage IIIB colon cancer. The fact that he was so enjoyable and had such a positive outlook, despite all the hardships he was currently going through, made him really stand out among most patients. The focus of this study will be on colon cancer, because of the fact that J.W. will have to battle this disease for quite some time. Social History: J.W. used to fly planes, and became homeless after he turned down a pilot job due to his ailing health. He is single and has no children. His brother lives in the area and visited him often during his stay at AMC. J.W. has no health insurance, so he was unsure how he would be paying for the expenses from his stay. Since he has barely any money, his food supply is less than adequate and far from nutritious. He also does not smoke or drink alcohol. Normal Anatomy and Physiology of Applicable Body Functions: The colon and rectum are parts of the gastrointestinal (GI) system. The stomach and the small intestine make up the first part of the GI tract. This is where food is processed for energy. The colon and the rectum make up the last part of the GI tract, where solid waste is passed out of the body. The small intestine is about 20 feet long. It is narrower than the large intestine but longer than the large intestine, which is only 5 feet long.1 The colon has four different sections: ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon, and sigmoid colon. The ascending colon starts with the cecum, where the small bowel attaches to the colon and extends up to the right side of the abdomen. The transverse colon extends across the body from the right to the upper, left abdomen. The descending colon extends downward on the left side of the abdomen. The sigmoid colon extends in the shape of an “S.” After the waste travels through the various parts of the colon it is considered stool, and then flows into the rectum; the last six inches of the digestive system. The stool is stored in the rectum until it is passed through the anus.1 Past Medical History: J.W. does not have any past medical history. Present Medical Status and Treatment: Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer (excluding skin cancers) diagnosed in men and women in the United States. In 2014, according to the American Cancer Society’s estimates for colorectal cancer, there are 96,830 new cases of colon cancer and 40,000 new cases for rectal cancer.1 The risk of developing colorectal cancer is about 1 in 20 (5%). It is the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in men and women combined, making up about 50,310 deaths during 2014.1 Over the past 20 years, death rates have been dropping. There are now more than 1 million survivors of colorectal cancer in the U.S.1 Certain risk factors can contribute to developing colorectal cancer. About 90% of people with this disease are over the age of 50. 2 The average age of diagnosis is 72 years old. A personal history of colorectal polyps increases the risk of developing colorectal cancer. Also, if one has already had colorectal cancer, even though it was removed, there is an increased risk of developing new cancers in other areas of the colon and rectum. Those with type II diabetes have an increased risk as well, especially with a less favorable prognosis. Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which includes ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, increases the risk of developing the disease. In addition, it often occurs in people with a family history of the disease or adenomatous polyps. About 5-10% who develop the disease have inherited mutations that cause it.1 First-degree relatives with a history of colorectal cancer are at an even higher risk. The two most common inherited syndromes linked with colorectal cancers are familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC). FAP is caused by mutations in the APC gene that is inherited from parents. About 1% of colorectal cancers are caused by the mutation of the FAP gene.1 Those individuals with FAP usually start having problems in their early teens or adulthood. Hundreds and thousands of polyps can form, and cancer usually develops by age 20. Usually by age 40 many people with FAP will already have colon cancer if the colon is not removed. The second inherited syndrome, HNPCC (or Lynch syndrome), accounts for about 2-4% of colorectal cancers.1 Usually this disorder is the result of the genes MLH1 or MSH2. Unlike FAP, this syndrome only causes a few polyps and does not begin at such an early age. However, individuals with this syndrome can be at an 80% increased risk in developing the disease.1 The other three syndromes linked with the disease are Turcot syndrome, PeutzJeghers syndrome, and MUTYH-associated polyposis.1 Turcot syndrome consists of two types: one can be caused by mutations in which cases the brain tumor are medulloblastomas, and the other can cause mutations in which cases the brain tumors are glioblastomas.1 Those with the rare, inherited condition known as Peutz-Jeghers syndrome have freckles around the mouth, and a type of polyp known as hamartomas, in their digestive tracts.1 This syndrome is caused by the mutations in the gene STK1. Finally, those with MUTYH- associated polyposis develop colon polyps, which can become cancerous if the colon is not removed.1 There is also an increased risk in bladder, ovarian, skin, and small intestine cancers as well. Life-style related factors also play significant roles in the risk of developing colorectal cancer. Diet, weight, and exercise are very significant in colorectal cancer risk. These certain life-style risk factors include: diet high in red meats and processed meats, physical inactivity, obesity, smoking, and heavy alcohol abuse.3 Colorectal cancer begins when healthy cells that make up the lining of the colon or rectum change and grow uncontrollably.4 These cells can eventually form a mass or tumor, and can either be benign (noncancerous) or malignant (cancerous). Colorectal cancer usually begins as a polyp, a noncancerous growth that may develop on the inner wall of the colon or rectum. Adenomatous polyps can change into cancer. Hyperplastic and inflammatory polyps are usually not pre-cancerous. Most polyps form a mound on the wall of the colon, while about 10% are flat and difficult to find with a colonoscopy.4 These types of polyps require a dye to show that they exist. If cancer forms in a polyp, it can eventually grow into the wall of the colon or rectum. Cancer can then spread to the blood or lymph vessels, lymph nodes, and to different parts of the body, such as the liver, lungs, peritoneum, or a woman’s ovaries.4 This spread of cancer throughout distant parts of the body is called metastasis. During this process, cancer cells can start to grow and develop new tumors. Colorectal cancer may cause a variety of different symptoms. These include: a change in bowel habits, such as diarrhea, constipation, or narrowing of the stool; pain without a bowel movement; feeling that the bowel does not empty completely; rectal bleeding, dark stools, or blood in the stool; cramping or abdominal pain; weakness and fatigue; and/or unintended weight loss.1 J.W. presented to AMC with many of these symptoms, including abdominal pain, unintentional weight loss, fatigue, weakness, diarrhea, and constipation. J.W.’s medications can be found in Appendix 1.5 Laboratory values can be found in Appendix 2. There are different tests to diagnose cancer and to find out if it has spread. Most often people will develop symptoms after the cancer has already developed. If a person develops with any of the signs or symptoms for colorectal cancer, a doctor will review medical history and conduct a physical examination. Different blood tests may be ordered, such as complete blood count, liver enzymes, or tumor markers (CEA).1 High levels of CEA can indicate that the cancer has spread to different parts of the body. It is often used as a marker in those already receiving treatment, versus screening or diagnosing. Sometimes colorectal cancer bleeds into the large intestine or rectum. People with this disease may then become anemic. In J.W.’s case this did occur, because his doctor diagnosed him with microcytic anemia. In addition, there are certain tests and procedures that can be done to detect colorectal cancer. These include: colonoscopy, biopsy, molecular testing of the tumor, CT scan, MRI, ultrasound, chest x-ray, and PET scan.1 The different types of treatment for colon and rectal cancer include surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy. For the colon, an open colectomy, laparoscopic assisted colectomy, or polypectomy can be done. A colectomy (sometimes called hemicolectomy, partial colectomy, or segmental resection) removes part of the colon and nearby lymph nodes.1 A laparoscopic assisted colectomy involves a small video camera that allows the surgeon to see inside the abdomen and remove the diseased part of the colon and nearby lymph nodes.1 A polypectomy involves the removal of a polyp through a colonoscope.1 For rectal cancer a polypectomy can be performed, where an instrument is inserted through the anus and polyps are removed. In a transanal resection, an instrument is inserted through the anus and cuts through all the layers of the rectum to remove any cancerous tissues.1 Low anterior resections are for more advanced stages of colorectal cancer, such as stage II or III. This procedure is used in rectal cancers that are closer to the colon. In this operation, the part of the rectum containing the tumor is removed. The colon is then attached to the remaining part of the rectum, so that bowels can move regularly after surgery.1 Sometimes the entire rectum will need to be removed in most stage II and III rectal cancers. This is called a proctectomy. With a colo-anal anastomosis, the colon can be connected to the anus.1 An abdominoperineal resection (APR) can be used to treat some stage I and stage II and III rectal cancers in the lower part of the rectum, near the anus. In this procedure, the surgeon will remove the anus, sphincter muscle, and tissues around it.1 A permanent colostomy will be needed after the procedure. Finally, a pelvic exenteration is recommended if the rectal cancer is spreading to nearby organs. The rectum will be removed, along with the bladder, prostate in men, or uterus in women if the cancer has spread.1 A colostomy will be needed due to the removal of the rectum. A urostomy will be needed if the bladder is removed. Radiation therapy is another treatment for either colon or rectal cancer. Radiation therapy involves high-energy rays or particles to destroy cancer cells. It can be used in those with colon cancer that has spread to the lining of the abdomen or other organs. It is also used to help treat cancer that has spread to the bones or brain. For rectal cancer, radiation therapy can either be given before or after surgery. This helps prevent the cancer from coming back. It is usually given along with chemotherapy, known as chemoradiation.4 Chemoradiation is often used in rectal cancer patients before surgery to avoid a colostomy, reduce scarring of the bowel where radiation was given, and decrease the chance the cancer will recur.4 Certain side effects of radiation therapy include: skin irritation at the site of radiation; nausea; rectal irritation causing diarrhea, painful bowel movements, or blood in the stool; bowel incontinence; bladder irritation; fatigue/tiredness; and/or sexual problems.1 Chemotherapy is another colorectal cancer treatment route. It can be given in different ways: systemic or regional. Systemic chemotherapy uses drugs that are injected into a vein or given by mouth.1 These drugs then enter the bloodstream and travel to all different areas of the body. In regional chemotherapy, drugs are injected directly into an artery leading to a part of the body containing a tumor.1 This approach causes fewer side effects. There are also various drugs that can be used to treat colorectal cancer. Chemotherapy cycles usually last about two to four weeks, and people usually get several cycles of treatment for about six months. The drugs most often used for colorectal cancer include: FOLFOX (a type of combination chemotherapy used to treat colorectal cancer); Camptosar (used when colon cancer has metastasized or returned); Avastin (used when colorectal cancer has spread, it starves tumors of blood and oxygen); Erbitux (it helps to stop cancer cells from reproducing); or Vectibix (used when colorectal cancer has spread despite chemotherapy). 3 The common side effects of these drugs include: hair loss; mouth sores; loss of appetite; nausea and vomiting; low blood counts. Chemotherapy can also lead to increased infections, easy bruising or bleeding, and fatigue.1 Those with colorectal cancer are given stages in with their diagnosis. The stage helps describe where the cancer is located, if or where it has spread, and whether or not it is affecting other parts of the body.1 The stage is an important factor in determining prognosis and treatment options.4 Stage 0: Also known as “carcinoma in situ”, where the cancer cells are only found in the mucosa (inner lining) of the colon or rectum. Stage I: The cancer has grown through the mucosa and has invaded the muscular layer. It has no yet spread to lymph nodes or distant sites. Stage IIA: The cancer has grown into the outermost layers of the colon or rectum, but as not gone through them. Stage IIB: The cancer has grown through the layers of the muscle to the visceral peritoneum. It still has not spread. Stage IIC: The tumor has spread through the wall of the colon or rectum and has grown into or attached to nearby tissues or organs. Stage IIIA: The cancer has grown through the inner lining or into the muscle layers of the intestine. It has spread to one or three lymph nodes, or into other areas of fat near the lymph nodes. Stage IIIB: The cancer has grown through the bowel wall or into surrounding organs. It has spread to one to three lymph nodes. Stage IIIC: The cancer of the colon, regardless of how deep it has grown, has spread to four or more lymph nodes, but not to other distant parts of the body. Stage IVA: The cancer has spread to one other part of the body, such as the liver or lungs. Stage IVB: The cancer has spread to more than one distant organ or set of lymph nodes, or it has spread to distant parts of the peritoneum. During J.W.’s stay at AMC, an ultrasound was done and showed a mass-like area in the abdomen as well as a cyst in the right kidney. A GI consult was placed to have an EGD/colonoscopy with a small bowel biopsy and rectal polypectomy. The postoperative diagnoses included diverticulosis, mass in the colon, and rectal polyp. Also, in the mid to proximal transverse colon, there was a mass that was most likely cancerous. On February 21, a right hemicolectomy procedure was done. A right hemicolectomy is a surgical procedure performed on those patients with cancer between the cecum and ascending colon. J.W. would have to wait for the pathology results. An oncology consult was placed due to the likelihood that the mass would be cancerous. On February 24, the pathology results showed that J.W. had stage IIIB colon cancer. With this stage, surgery (colectomy) and adjunct chemotherapy (chemo after surgery) are the standard treatments.6 Adjunct chemotherapy works by killing any cancer cells that may have been left behind after surgery.6 It helps kill the rest of the cells that may have escaped from the tumor and spread to different parts of the body. J.W. would need to have a port placed in the future for chemotherapy. Medical Nutrition Therapy: Due to the fact that J.W. is homeless, he is never sure when his next meal will be, where it will be, or what it will be. J.W. reports that since he only has a limited amount of finances, he can only afford to purchase really cheap food items. He will accept anything that is offered to him. Since it was difficult to obtain a usual eating pattern, J.W. provided an example of a day’s worth of food. For breakfast, he will have about 1 cup of oatmeal. For lunch, he will have two McDonald’s cheeseburgers. For supper, he will have potato chips and a slice of pizza. Provided below is an example of a 24-hour recall in J.W.’s day. This diet was analyzed using “Super Tracker” from the USDA website.7 Calories 1887 kcals Protein 88 grams Carbohydrate 171 grams Fiber 14 grams Total fat 96 grams Saturated fat 38 grams Cholesterol 241 mg Sodium 3618 mg J.W. was placed on the diabetic high diet during the later part of his stay. At first, he was NPO for the EGD/colonoscopy and the hemicolectomy. After that, he was placed on full liquids on February 22. The doctor advanced him to a Regular diet on February 24. Since he was recently diagnosed with diabetes, it was important for him to maintain good blood sugar control. A “Dear Doctor” note was left requesting that J.W. be placed on the diabetic high det. The diabetic high diet limits calories to 2,000-2,500, cholesterol <200 mg, sodium 2300-2400 mg, and total fat to 25-35% of calories. The daily carbohydrate allowance on a diabetic high diet is about 225-240 grams/day. Not many people at AMC are placed on the diabetic high diet. The reason he needed those extra calories was because of his significant weight loss and malnutrition. Using the Hamwi formula for ideal body weight, J.W. should be around 165 pounds. His estimated energy needs were based on 25-30 kcal/kg. This calculated out to be around 2,075- 2,490 calories/day. His protein needs were based on 1.0-1.2 grams/kg due to his protein-energy malnutrition from unintentional weight loss. This calculated out to be around 86-100 grams protein/day. After it was confirmed that J.W. had stage IIIB colon cancer, his estimated needs were increased. His estimated energy needs were increased to 30-35 grams/kg and his protein needs increased to 1.2-1.5 grams/kg. Therefore, his estimated calorie needs were 2,430-2,835, and his protein needs were 97-122 grams/day. J.W understood the need to be on the diabetic diet at AMC. During his stay he was constantly given education on diabetes management due to his new diagnosis. Since he was dealing with the new diagnosis of colon cancer as well, J.W. had a lot to deal with. It would not be easy trying to manage his diabetes on top of starting chemotherapy to treat his colon cancer. J.W. was intelligent enough to learn how to manage his diabetes. He was given the “Diabetes Inpatient Survival Skills” book that is full of information on diabetes management. Various nurses reviewed the material with him. During J.W.’s stay at AMC, the following nutrition related problems with supporting evidence were used: Unintended weight loss related to malabsorption as evidenced by 75 pounds weight loss (29%) over 6 months. Altered nutrition-related lab values related to newly diagnosed DM as evidenced by HgA1c of 9.0%. Increased calorie and protein needs related to newly diagnosed colon cancer stage IIIB as evidenced by biopsy results. Altered GI function related to changes in motility as evidenced by constipation x 5 days. Since J.W. was so malnourished from his unintentional weight loss, he agreed to drink a Glucerna oral supplement three times per day. During his stay, he actually lost an additional five pounds. He was very accepting and willing to try anything that would provide him with extra calories and protein. His oral intake on the diabetic high diet was excellent; 100% of most meals. He drank every Glucerna shake that was provided to him. He was also given Glucerna coupons so that he could purchase them once discharged. J.W. was provided with the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics handouts: Carbohydrate Counting for People with Diabetes, Fat Content of Foods List, and Fiber Content of Foods List. The importance of counting carbohydrates, eating meals consistently, checking blood sugars, and exercising were discussed with him. J.W. stated that once he felt better he was going to start exercising. He was encouraged to attend the Diabetes Wellness Center and a pamphlet was provided to him. J.W. was also informed about the importance of eating fiber-rich foods once his bowels returned to normal. The importance of avoiding high fat foods (especially red meats) was continually stressed. He was consuming a lot of red meats before his admission to AMC. His diet was also lacking fruits and vegetables due to the lack of convenience and availability. He had issues with constipation during his stay. He did not end up having a bowel movement until he was discharged on February 26. J.W. is a very intelligent man. All the diet education that was provided to him he was willing to learn and apply. His brother was with him during the majority of his stay. When it was asked where J.W. would be staying, his answer was not with his brother. He voiced that he would be staying with family friends in the area that would provide him with food and transportation to get to chemotherapy. It was not voiced why he would not be staying with his brother. However, his brother was very supportive during J.W.’s stay at AMC. He asked questions and provided information when J.W. was out of the room. According to Sylvia Escott-Stump, there are different nutritional recommendations to follow. A low-fat, high-fiber diet can prevent future polyps, and reduce the risk of adenoma recurrence. Fiber should be limited until the bowels return to normal, especially after surgery. Once the bowels start functioning properly, the diet should be rich in whole gains, fruits, and vegetables (especially cruciferous). Red meat should be consumed less. Instead, more poultry, fish, tofu, and beans should be consumed for protein. This will help decrease saturated fat intake. Omitting trans fatty acids is also suggested. It is also important to consume the healthy unsaturated fats, such as flaxseed, salmon, canola oil, and olive oil. Caffeine and other stimulants, such as alcohol and tobacco are strongly discouraged. Drinking 6-8 glasses of filtered water daily, as well as exercising at least 30 minutes, 5 days a week is encouraged.8 In addition, taking fish oil supplements can be helpful in reducing inflammation. Eating plenty of protective foods such as calcium-rich foods, lutein and lycopene (tomato products, watermelon, spinach, kale, greens, broccoli, and pink grapefruit), flavonoids (apples, onions, green tea, and chamomile tea), and selenium foods (Brazil nuts) is also encouraged. A multivitamin is beneficial, particularly for folic acid, and vitamins B6 and D3. Folic acid can also be found in spinach, broccoli, asparagus, avocado, orange juice, dried beans, and fortified cereals. Dairy products are also encouraged (if tolerated), for calcium and vitamin D. Before J.W. was discharged, he was aware that he would need to make a followup appointment to have a port placed for chemotherapy. He was also being sent home with Metformin, as well as glucose test strips and a meter. His doctor already set him up to receive a free class at the Diabetes Wellness Center, which he would be attending in April. It was encouraged that J.W. follow the nutritional guidelines that were provided to him in the handouts. Prognosis: Due to J.W.’s willingness to keep fighting for his life, there is no doubt that he will take control of his diabetes and colon cancer. His doctor had already set him up for a free class at the Diabetes Wellness Center, which he stated that he was going to attend. He also knew that his diet would have to change. Since he would be living with family friends, food would be provided to him so that he would not have to rely on cheap McDonald’s cheeseburgers, chips, and pizza for nutrition. He was also willing to start chemotherapy to kill any remaining cancerous cells. Since his colon cancer is stage IIIB, it has not yet spread to other organs in the body. The doctors have a lot of faith in him that he is going to do well, especially with how driven he is to make a full recovery. Summary: This case study was definitely an eye-opener. This man could have easily given up on himself. He was homeless and was also diagnosed with diabetes mellitus and stage IIIB colon cancer in the span of a few days. However, after speaking with J.W., he was very calm and collected about his diagnoses. He was willing to learn. He was willing to do anything he could in order to fight his diabetes and colon cancer. I was able to learn a lot about him and have quality conversations with him about various topics. He told me riddles (none of which I could solve), and told me how proud he was in how far I have come in my career. Despite the fact that so many negative things were happening to him, he was one of the most positive people I have come into contact with at AMC. I have no doubt in my mind that he will live a long and happy life. He has what it takes to fight cancer; willpower and motivation. Bibliography: 1. "Colorectal Cancer." American Cancer Society, 2013. Web. 21 Apr. 2014. <http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/cid/documents/webcontent/003096-pdf.pdf>. 2. "Colon Cancer Treatment." Treatment for Colon Cancer. N.p., 2014. Web. 21 Apr. 2014. 3. "Colorectal Cancer." University of Maryland Medical Center. N.p., 2014. Web. 21 Apr. 2014. 4. "Colorectal Cancer." Cancer.net. American Society of Clinical Oncology, 2014. Web. 21 Apr. 2014. 5. Pronsky ZM, Crowe JP. Food Medication Interactions. 17th edition. Birchrunville, PA: Food-Medication Interactions; 2012 6. "Colorectal Cancer." Welcome to the Johns Hopkins Colon Cancer Center. N.p., 2001-2014. Web. 21 Apr. 2014. 7. "SuperTracker." ChooseMyPlate.gov. United States Department of Agriculture, 2014. Web. 21 Apr. 2014. 8. Escott-Stump, Sylvia. "Colorectal Cancer." Nutrition and Diagnosis- Related Care. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2012. 759-62. Print. 9. Mahan, L. Kathleen., and Sylvia Escott-Stump. "Medical Nutrition Therapy in Cardiovascular Disease." Krause's Food, Nutrition, & Diet Therapy. 11th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2004. 730-731. Print. 10. "Colon Cancer Nutrition." EMedTV: Health Information Brought To Life. Clinaero, Inc, 2006-2014. Web. 21 Apr. 2014. Appendix 1 Drug Use and Purpose Cefotan Antibiotic Heparin Anticoagulant Zofran Antiemetic, antinauseant Sennagen Laxative, stimulant Venofer Hematinic, antianemic, mineral supplement, iron deficiency treatment Drug/Food Interactions N/A Caution with diabetes and ESRDhyperkalemia. Caution with ↓ hepatic or ↓ renal function N/A Side Effects Blood/Serum Anorexia, oral candidiasis and sore mouth and tongue with long term use, nausea/vomiting, diarrhea Bleeding, hemorrhage, dizziness, headache, bruising Eosinophilia Dry mouth, abdominal pain, constipation, diarrhea, headache, fatigue, dizziness, hypoxia, fever/chills, flushing, hiccups, rash, drowsiness N/A Electrolyte balance with excessive use, ↑ intestinal peristalsis, bowel movement in 6-12 hours, nausea/vomiting, cramps, diarrhea, laxative dependence and loss of normal bowel function with long term use/abuse May take with Anorexia, dental food to ↓ GI stains with liquid distress, but food forms, ↓ absorption by nausea/vomiting, 50%. Take one dyspepsia, bloating, hour before or 2 constipation, after bran, high diarrhea, dark stools phytate foods, fiber supplement, tea, coffee, red grape ↑ AST, ALT, PT/INR, ↓ platelets N/A N/A ↑ Hb, HCT, ferritin, Fe, % transferrin saturation, ↓ TIBC Protonix Decadron juice/wine, soy, dairy products or egg. 200 mg Vit C/ 30 mg Fe will ↑ absorption. Meat/fish/poultr y ↑ absorption. Take carbonate antacids, Ca, P, Zn, or Cu supplemented separately by ≥ 2 hour. Antigerd, N/A May decrease antisecretory absorption of iron, decrease absorption of B12, ↓ gastric acid secretion, ↑ gastric pH, diarrhea Corticosteroid, Take with food Esophagitis, antito ↓ GI effects. nausea/vomiting, inflammatory, Ca-Vit D dyspepsia, peptic immunosuppress supplement ulcer, bloating, GI ant recommended bleeding/perforation, with long term ↑ appetite, ↑ wt, use. Caution negative nitrogen with balance due to grapefruit/relate protein catabolism, d citrus. cancer wasting with long term use, Cr deficiency may ↑ risk for steroid induced diabetes, edema, ↑ BP, insomnia, masking of infection, slow healing, bruising, weakness, dizziness, headache, osteoporosis/necrosis , fractures, muscle wasting, cataracts, pancreatitis, adrenocortical insufficiency, Cushing’s syndrome, ↓ growth in children ↑ gastrin ↑ Na, Glucose, ↓ K, Ca Lantus & Humalog Antidiabetic, hypoglycemic N/A ↑ wt, alcohol ↑ hypoglycemic effect, caution with severe hypoalbuminemia, caution with decreased hepatic or renal function, hyper or hypothyroidism, hypoglycemia ↓ glucose, Hb A1c Appendix 2 Labs- 2/21/14 Glucose HgA1c Serum Albumin CRP Calcium Iron IBC Hemoglobin Hematocrit RBC MCV MCH MCHC RDW Actual Lab 358 mg/dl 9.0% 2.3 gm/dl 9.37 mg/dl 8.0 mg/dl 9 ug/dl 240 ug/dl 5.6 gm/dl 22.3% 3.62 m/ul 61.6 fl 15.5 pg 25.1 g/dl 18.8% Normal Range 70-100 mg/dl 4.2-6.3% 3.5-5.0 mg/dl 0-0.30 mg/dl 8.7-10.2 mg/dl 42-135 ug/dl 250-450 ug/dl 14-18 gm/dl 42-52% 4.7-6.1 m/ul 80-94 fl 27-31 pg 32-36 g/dl 12-15% High High Low High Low Low Low Low Low Low Low Low Low High Labs- 2/24/14 Glucose HgA1c Serum Albumin CRP Calcium Iron IBC Hemoglobin Hematocrit RBC MCV MCH MCHC RDW % Neutrophils % Lymphocytes Absolute Lymphocytes Actual Lab 137 mg/dl 9.0% 2.3 gm/dl 9.37 mg/dl 8.1 mg/dl 9 ug/dl 240 ug/dl 7.8 gm/dl 28.8% 4.20 m/ul 68.6 fl 18.6 pg 27.1 g/dl 25.2 % 78% 11% 0.76 k/ul Normal Range 70-100 mg/dl 4.2-6.3% 3.5-5.0 mg/dl 0-0.30 mg/dl 8.7-10.2 mg/dl 42-135 ug/dl 250-450 ug/dl 14-18 gm/dl 42-52% 4.7-6.1 m/ul 80-94 fl 27-31 pg 32-36 g/dl 12-15% 40-74% 19-48% 0.9-5.2 k/ul High High Low High Low Low Low Low Low Low Low Low Low High High Low Low Labs- 2/25/14 Potassium Creatinine Glucose HgA1c Serum Albumin CRP Calcium Iron IBC Hemoglobin Hematocrit RBC MCV MCH MCHC RDW % Neutrophils % Lymphocytes Absolute Lymphocytes Actual Lab 3.3 MEQ/l 1.6 mg/dl 139 mg/dl 9.0% 2.3 gm/dl 9.37 mg/dl 7.9 mg/dl 9 ug/dl 240 ug/dl 7.9 gm/dl 28.3% 4.12 m/ul 68.7 fl 19.2 pg 27.9 g/dl 25.2 % 74% 14% 0.76 k/ul Normal Range 3.5-5.3 MEQ/l 0.4-1.5 mg/dl 70-100 mg/dl 4.2-6.3% 3.5-5.0 mg/dl 0-0.30 mg/dl 8.7-10.2 mg/dl 42-135 ug/dl 250-450 ug/dl 14-18 gm/dl 42-52% 4.7-6.1 m/ul 80-94 fl 27-31 pg 32-36 g/dl 12-15% 40-74% 19-48% 0.9-5.2 k/ul Low High High High Low High Low Low Low Low Low Low Low Low Low High WNL Low Low