example

advertisement

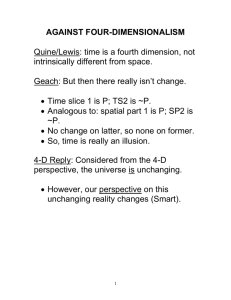

Ryan Wasserman Philosophy 430 DWA #1 (Example) 438 words One of the central debates about time is a debate over ontology (or what exists). According to the Eternalist, past and future times (and objects, and events) are like distant places. The north pole and the south pole both exist, they just don’t exist here (in Bellingham). In the same way, the Eternalist says that the 1st century and the 31st century both exist, they just don’t exist now. The Presentist disagrees. She says that future and past times are more like fictional times and places—they don’t really exist. According to the Presentist, everything that exists, exists now. I am unsure which of these views (if either) is correct, but Presentism certainly seems like the more natural view, and that seems to count for something. Of course, Presentism also faces certain challenges. Three of these are mentioned by Ned Markosian in his paper “Time”. Markosian puts the first objection as follows: One such problem is that the view seems to lead to the conclusion that nothing at all really exists. After all, the present is razor-thin; it is vanishingly small. In fact, the present seems to have zero temporal extension. So it seems like the Presentist’s ontology contains nothing. And that certainly seems problematic. (page 39) This objection does not strike me as very serious. The stated premise is that everything in the Presentist’s ontology has zero temporal extent, and the conclusion is that the Presentist’s ontology doesn’t include anything. This argument obviously relies on the following implicit claim: In order for something to exist, it must have positive temporal extent. But this seems clearly mistaken. Even the Eternalist, for example, believes in instants of time, and instants have zero temporal extent. The Presentist just says that everything is always like that. The second objection focuses on the fact that we often seem to think about, talk about, or admire past people. For example, we can say that Socrates was a philosopher or that John admires Socrates (Markosian, page 40). Yet the Presentist says that Socrates doesn’t exist. So how could we say anything about him or admire him? In order for there to be admiration, you need an admirer and an admireree. This objection also strikes me as weak. After all, even the Eternalist should grant that we can talk about or admire fictional characters. But fictional characters don’t exist. So, there must be some sense in which you can admire things that aren’t real. The third main objection that Marksosian discusses is that Presentism seems incompatible with our best physical theory (especially relativity). This seems like a much more serious worry (maybe the biggest worry) for Presentists, but I don’t have time to fully address that worry here.