CSS_WhitePaper_Adver..

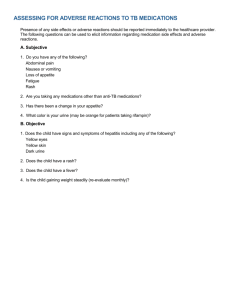

advertisement

DRAFT 1 1. Analyses and Displays Associated with Adverse Events – Focus on Adverse Events in Phase 2-4 Clinical Trials and Integrated Summary Documents Version 1.0 Created xx XXXX 201x A White Paper by the PhUSE Computational Science Development of Standard Scripts for Analysis and Programming Working Group Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the opinions of PhUSE, members' respective companies or organizations, or regulatory authorities. The content in this document should not be interpreted as a data standard and/or information required by regulatory authorities. NOTE TO REVIEWERS: This is the first draft being sent for broad review. The intent is to get initial feedback on the proposed tables and figures, so please focus on Section 7. Comments on the other sections are still welcome. Page 1 DRAFT 1 2. Table of Contents Section Page 1. Analyses and Displays Associated with Adverse Events – Focus on Adverse Events in Phase 2-4 Clinical Trials and Integrated Summary Documents ......................................................................1 2. Table of Contents ....................................................................................................................2 3. Revision History ......................................................................................................................4 4. Purpose ....................................................................................................................................5 5. Introduction .............................................................................................................................6 6. General Considerations ...........................................................................................................7 6.1. Importance of Visual Displays ...........................................................................................7 6.2. P-values and Confidence Intervals .....................................................................................7 6.3. Conservativeness ................................................................................................................8 6.4. Number of Therapy Groups................................................................................................8 6.5. Multi-phase Clinical Trials .................................................................................................8 6.6. Integrated Analyses ............................................................................................................8 6.7. Adverse Event Definitions .................................................................................................8 6.8. Adverse Event Data Collection ..........................................................................................9 6.9. Adverse Event Categories and Preferred Terms ..............................................................10 6.10. Adverse Event Severity ....................................................................................................10 6.11. Adverse Event Relatedness Assessment by the Investigator ...........................................10 6.12. Calculating Percentages using Population-Specific Denominators .................................11 6.13. Exposure-Adjusted Summaries ........................................................................................11 6.14. Time-to-Event Summaries................................................................................................11 7. Tables and Figures for Individual Studies .............................................................................12 7.1. Recommended Displays ...................................................................................................12 7.2. Discussion...........................................................................................................................1 8. Tables and Figures for Integrated Summaries .........................................................................3 8.1. Recommended Displays .....................................................................................................3 8.2. Discussion...........................................................................................................................3 9. Example SAP Language ..........................................................................................................4 9.1. Individual Study .................................................................................................................4 9.2. Integrated Summary ...........................................................................................................4 10. References ...............................................................................................................................5 11. Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................6 12. Appendix .................................................................................................................................7 Page 2 DRAFT 1 Page 3 DRAFT 1 3. Revision History Version 1.0 was finalized xx XXXX 201x. Page 4 DRAFT 1 4. Purpose The purpose of this white paper is to provide advice on displaying, summarizing, and/or analyzing adverse events, with a focus on Phase 2-4 clinical trials and integrated summary documents. The intent is to begin the process of developing industry standards with respect to analysis and reporting for measurements that are common across clinical trials and across therapeutic areas. This advice can be used when developing the analysis plan for individual clinical trials, integrated summary documents, or other documents in which adverse events are of interest. Although the focus of this white paper pertains to specific safety measurements (common adverse events, dropouts and other significance adverse events, deaths, etc), some of the content may apply to other measurements (e.g., different safety measurements and efficacy assessments). Similarly, although the focus of this white paper pertains to Phase 2-4, some of the content may apply to Phase 1 or other types of medical research (e.g., observational studies). Development of standard Tables, Figures, and Listings (TFLs) and associated analyses will lead to improved standardization from collection through data storage. (You need to know how you want to analyze and report results before finalizing how to collect and store data.) The development of standard TFLs will also lead to improved product lifecycle management by ensuring reviewers receive the desired analyses for the consistent and efficient evaluation of patient safety and drug effectiveness. Although having standard TFLs is an ultimate goal, this white paper reflects recommendations only and should not be interpreted as “required” by any regulatory agency. Detailed specifications for TFL or dataset development are considered out-of-scope for this white paper. However, the hope is that specifications and code (utilizing SDTM and ADaM data structures) will be developed consistent with the concepts outlined in this white paper, and placed in the publicly available PhUSE Standard Scripts Repository. Page 5 DRAFT 1 5. Introduction Industry standards have evolved over time for data collection (CDASH), observed data (SDTM), and analysis datasets (ADaM). There is now recognition that the next step would be to develop standard TFLs for common measurements across clinical trials and across therapeutic areas. Some could argue that perhaps the industry should have started with creating standard TFLs prior to creating standards for collection and data storage (consistent with end-in-mind philosophy), however, having industry standards for data collection and analysis datasets provides a good basis for creating standard TFLs. The beginning of the effort leading to this white paper came from the PhUSE Computational Science Collaboration, an initiative between PhUSE, FDA, and Industry where key priorities were identified to tackle various challenges using collaboration, crowd sourcing, and innovation (Rosario, et. al. 2012). Several Computational Science (CS) working groups were created to address a number of these challenges. The working group titled “Development of Standard Scripts for Analysis and Programming” has led the development of this white paper, along with the development of a platform for storing shared code. Most contributors and reviewers of this white paper are industry statisticians, with input from non-industry statisticians (e.g., FDA and academia) and industry and non-industry clinicians. Hopefully additional input (e.g., other regulatory agencies) will be received for future versions of this white paper. There are several existing documents that contain suggested TFLs for common measurements. However, many of the documents are now relatively outdated, and generally lack sufficient detail to be used as support for the entire standardization effort. Nevertheless, these documents were used as a starting point in the development of this white paper. The documents include: ICH E3: Structure and Content of Clinical Study Reports Guideline for Industry: Structure and Content of Clinical Study Reports Guidance for Industry: Premarketing Risk Assessment Reviewer Guidance. Conducting a Clinical Safety Review of a New Product Application and. Preparing a Report on the Review ICH M4E: Common Technical Document for the Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use - Efficacy The Reviewer Guidance is considered a key document. Several recommended displays related to adverse events are included. This white paper provides additional detail and some recommended improvements. Page 6 DRAFT 1 6. General Considerations This section contains some general considerations for the plan of analyses and displays associated with adverse events. 6.1. Importance of Visual Displays Communicating information effectively and efficiently is crucial in detecting safety signals and enabling decision-making. Current practice, which focuses on tables and listings, has not always enabled us to communicate information effectively since tables and listings may be very long and repetitive. Graphics, on the other hand, can provide more effective presentation of complex data, increasing the likelihood of detecting key safety signals and improving the ability to make clinical decisions. They can also facilitate identification of unexpected values. For the topic of adverse events, the use of tables and listings generally is more common for the summary of safety data. While adverse events can benefit some from visual displays, it may not be as much as other safety topics. Standardized presentation of visual information is encouraged. The FDA/Industry/Academia Safety Graphics Working Group was initiated in 2008. The working group was formed to develop a wiki and to improve safety graphics best practice. It has recommendations on the effective use of graphics for three key safety areas: adverse events, ECGs and laboratory analytes. The working group focused on static graphs, and their recommendations were considered while developing this white paper. In addition, there has also been advancement in interactive visual capabilities. The interactive capabilities are beneficial, but are considered outof-scope for this version of the white paper. 6.2. P-values and Confidence Intervals There has been ongoing debate on the value or lack of value for the inclusion of p-values and/or confidence intervals in safety assessments (Crowe, et. al. 2009). This white paper does not attempt to resolve this debate. As noted in the Reviewer Guidance, p-values or confidence intervals can provide some evidence of the strength of the finding, but unless the trials are designed for hypothesis testing, these should be thought of as descriptive. Throughout this white paper, p-values and measures of spread are included in several places. Where these are included, they should not be considered as hypothesis testing. If a company or compound team decides that these are not helpful as a tool for reviewing the data, they can be excluded from the display. Some teams may find p-values and/or confidence intervals useful to facilitate focus, but have concerns that lack of “statistical significance” provides unwarranted dismissal of a potential signal. Conversely, there are concerns that due to multiplicity issues, there could be overinterpretation of p-values adding potential concern for too many outcomes. Similarly, there are concerns that the lower- or upper-bound of confidence intervals will be over-interpreted. It is important for the users of these TFLs to be educated on these issues. Page 7 DRAFT 1 6.3. Conservativeness The focus of this white paper pertains to clinical trials in which there is comparator data. As such, the concept of “being conservative” is different than when assessing a safety signal within an individual subject or a single arm. A seemingly conservative approach may end up not being conservative in the end. For example, for studies that collect safety data during an off-drug follow-up period, one might consider it conservative to include the adverse events reported in the follow-up period. However, this approach may result in smaller odds ratios than including only the exposed period in the analysis. A conservative approach for defining outcomes, from a single arm perspective, is one that would lead to a higher number of patients reaching a threshold. However, a conservative approach for defining outcomes may actually make it more difficult to identify safety signals with respect to comparing treatment with a comparator (see Section 7.1.7.3.2 in the Reviewer Guidance). Thus, some of the approaches recommended in this white paper may appear less conservative than alternatives, but the intent is to propose methodology that can identify meaningful safety signals for a treatment relative to a comparator group. 6.4. Number of Therapy Groups The example TFLs show one treatment arm versus comparator in this version of the white paper. Most TFLs can be easily adapted to include multiple treatment arms or a single arm. 6.5. Multi-phase Clinical Trials The example TFLs show one treatment arm versus comparator within a controlled phase of a study. Discussion around additional phases (e.g., open-label extensions) is considered out-ofscope in this version of the white paper. Many of the TFLs recommended in this white paper can be adapted to display data from additional phases. 6.6. Integrated Analyses For submission documents, TFLs are generally created from using data from multiple clinical trials. Determining which clinical trials to combine for a particular set of TFLs can be complex. Section 7.4.1 of the Reviewer Guidance contains a discussion of points to consider. Generally, when p-values are computed, adjusting for study is important. Creating visual displays or tables in which comparisons are confounded with study is discouraged. Understanding whether the overall representation accurately reflects the review across individual clinical trial results is important. 6.7. Adverse Event Definitions As discussed in the Reviewer Guidance, an adverse event is any untoward medical occurrence associated with the use of a drug in humans, whether or not considered drug related. The use of a similar term, adverse reaction, is used to refer to an undesirable effect, reasonably associated with the use of a drug that may occur as part of the pharmacological action of the drug or may be unpredictable in its occurrence. Adverse reactions do not include all adverse events observed during the use of a drug, only those which there is some basis to believe a causal relationship exists between the drug and the occurrence of the adverse event. Page 8 DRAFT 1 Serious adverse events are adverse events occurring at any dose, whether or not considered to be drug-related, that results in any of the following outcomes: Death A life-threatening adverse experience Inpatient hospitalization or prolongation of existing hospitalization A persistent or significant disability/incapacity A congenital anomaly or birth defect Important medical events that may not result in death, be life-threatening, or require hospitalization may be considered serious adverse drug events when, based upon appropriate medical judgment, they may jeopardize the patient and may require medial or surgical intervention to prevent one of the outcomes listed above Non-serious adverse events are all adverse events which do not meet the above criteria for “serious”. [In development] The precise definition of a treatment emergent adverse event varies across the guidance documents, and all lack necessary detail for consistent implementation across the industry. As a point of note, the Reviewer Guidance document is silent on the definition of the treatment-emergent. Several other authors have discussed more precise definitions for treatmentemergence (Mary to insert references). Recommending a specific definition is considered outof-scope for this version of the white paper. It is assumed treatment-emergent adverse events are identified in analysis datasets and available for summaries/analyses. The specific detailed definition should be documented (protocol, Statistical Analysis Plan, study report methods section, etc.) 6.8. Adverse Event Data Collection There are several ways in which adverse event data can be collected for a study/product. Some methods for obtaining common adverse events include open-ended questioning, specific solication of particular adverse events, and checklists. Especially for open-ended questioning, the associated instructions for when to include an event for collection to the sponsor becomes important for truly understanding “adverse events” and “treatment-emergent adverse events”. The method of obtaining information should be carefully considered as there may be limitiations in interpretation depending on the collection approach. Across studies, consideration should be made to proactively collect adverse event data consistently. Recommending a specific method for collection and/or specific instructions associated with collection is considered out-of-scope for this white paper. We do hope CDISC/CDASH efforts continue to progress to assist in achieving more consistency in adverse event collection. [In development] Details around the collection of serious adverse events (SAEs) also varies across current practices. Certain SAEs are provided to sponsors and regulatory agencies expeditiously per regulations. However, collection into the clinical trial database can vary. Events meeting regulatory-defined seriousness (per FDA/ICH; reference to be added) are considered serious without controversy. As noted in the xxx guidance, other adverse events of interest can be defined as “serious”. Some sponsors include additional events for some Page 9 DRAFT 1 compounds, while others always stay with the regulatory-defined definition. A flag for seriousness if often embedded with adverse event collection. In some cases, the date in which the event became serious is included, in other collection methods it’s not. Etc. 6.9. Adverse Event Categories and Preferred Terms [In development] Investigator reported adverse events usually include verbatim terms. One commonly accepted approach to placing verbatim terms into appropriate adverse event cateogies prior to analyses includes mapping to a standard dictionary of preferred term, the most granular of these approaches being MedDRA. The TFL analyses proposed in this document generally assume that adverse events are appropriately mapped to adverse event categories and preferred terms in advance of analysis. As noted in xxx guidance, too granular of categorization can result in under-estimation (e.g., xxxx and xxx are different PTs but can be representing the same event in practice). Thus, grouping some events may be warrated for safety signal detection and for providing incidence rates for labeling Etc. [Add CTCAE] [Maybe something on SMQs – generally used for adverse events of special interest – usually AESIs are out-of-scope for these white papers, but since the use of SMQs is common, an generic display is included? For sponsor-defined groups of terms, a similar display can be used. Looking at all SMQs exploratory way – out-of-scope] 6.10. Adverse Event Severity [In development] Most common – mild/moderate/severe. CTCAE grades available for some. For purposes of this white paper, dispays will be provided for either method. 6.11. Adverse Event Relatedness Assessment by the Investigator [In development] As discussed in the Reviewer Guidance, the relatedness assessment made by the investigator is generally not considered useful. For purposes of this white paper, we assume at least one regulatory agency and/or sponsor will want a summary of events considered related by the investigator, thus a recommended display is included. The collection of relatedness is not defined in CDISC/CDASH and is defined by the sponsor. Thus, collection varies (yes/no, yes/no/unknown, no/probable/possibly/likely, missing allowed, missing not allowed, etc.) and will likely continue to vary unless CDISC/CDASH efforts continue to progress. For this version of the white paper, we assume relatedness was either collected as yes/no or the collected categories are grouped to yes/no. We assume unknown and missing are not allowed. Any derivations into defining relatedness as yes/no, if required, should be documented (protocol, Statistical Analysis Plan, study report methods section, etc.). Page 10 DRAFT 1 6.12. Calculating Percentages using Population-Specific Denominators [In development] Some events only occur in a particular gender…. Some events only occur in pediatric subjects, geriatric, etc….. MedDRA provides a list of gender-specific adverse events and pediatric-specific adverse events. Theoretically, percentages for many events can be created using a denominator from only those demographics that can have the event. In practice, we recommend only attempting such adjustments for gender and pediatric (when both pediatric and adults are included in a study) as a consistent identification is provided by MedDRA…. Review Guidance highlights gender as something to create gender denominators for… 6.13. Exposure-Adjusted Summaries [In development] Include situations where such summaries are warranted for signal detection vs not warranted 6.14. Time-to-Event Summaries [In development] Include situations where such summaries are warranted for signal detection vs not warranted Page 11 DRAFT 1 7. Tables and Figures for Individual Studies 7.1. Recommended Displays As noted in ICH E3, a brief summary of adverse events is expected. To provide the basis for a brief summary, an overview table is very helpful (Table 7.1) and is recommended. It provides a high level summary of the more detailed tables for adverse events. For a more detailed summary of adverse events, Tables 7.2-7.4 and Figure 7.1 are recommended. Table 7.2 provides a summary of all treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs), and is sorted by System Organ Class as recommended in ICH E3 and in the example table in the Reviewer Guidance. Table 7.3 (a side-by-side table of all TEAEs next to the TEAEs considered related by the investigator) is recommended primarily to support shared learning that at least one regulatory agency will expect it (See Section 6.11). As noted in the Reviewer Guidance and ICH E3, a summary of the most common TEAEs is expected. The definition of common TEAEs, according to the Reviewer Guidance, are those TEAEs generally occurring at a rate of 1 percent of more, however a higher cut off than 1 percent may be considered if doing so does not lose important information. Although a table is typically produced for the most common TEAEs (by simply subsetting on the table of all TEAEs), Figure 7.1 is recommended as a more visual, user-friendly way to view the data. Table 7.4a or Table 7.4b is recommended to display maximum severity or maximum CTCAE grade (depending on collection). Although the Reviewer Guidance does not indicate an expectation for such a display, it is noted in ICH E3 and is frequently useful for overall interpretation of adverse event data. As noted in the Reviewer Guidance and ICH E3, a listing of deaths is expected and is recommended (Listing 7.1). Although the guidance documents do not specifically refer to a summary of serious adverse events (only a listing), we believe a summary table of all serious events during the treatment period is very helpful for data interpretation (Table 7.5). If the number of SAEs is expected to be extremely small, then a listing would be sufficient. The recommended summary table displays all preferred terms by decreasing frequency without sorting by System Organ Class. The table could be sorted by System Organ Class if deemed useful (e.g., a lot of SAEs across a number of System Organ Classes). To further understand the severity of adverse events, a summary of adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation is recommended (Table 7.6). The guidance documents do not specifically refer to a summary table (only a listing), but it is commonly created across the industry and is considered very useful in understanding tolerability. Table 7.7 is recommended when there is a topic of special interest that can be defined by the use of a Standardized MedDRA Query (SMQ). SMQs were created to define common medical concepts of interest by grouping relevant MedDRA preferred terms (reference). Although topics of special interest are considered out-of-scope for this white paper, it is included since it’s common for compounds to have at least one SMQ of interest. Page 12 DRAFT 1 Table 7.1 Overview of Subject Incidence of Adverse Events Safety Population Treatment Emergent Adverse Events Treatment-Emergent Adverse Events Related to Study Treatment Serious Adverse Events Adverse Events leading to Discontinuation of Investigational Product Fatal Adverse Events Treatment A (N=XX) n (%a) Treatment B (N=XX) n (%a) xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) P-value b xx xx xx xx xx Notes: Subjects may be counted in more than one row. aDenominator bP-value for each % is the treatment column N from Fisher’s Exact Test 13 DRAFT 1 Table 7.2 Summary of Treatment-Emergent Adverse Events by Preferred Term in Descending Frequency within System Organ Class Safety Population Treatment 1 Treatment 2 (N = XX) (N = XX) n (%a) n (%a) P-valueb xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx [Preferred Term #1] xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx [Preferred Term #2]c xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx System Organ Class Preferred Term Number of subjects reporting treatmentemergent adverse events [System Organ Class #1] [System Organ Class #2] [Preferred Term #1]d …. aDenominator for each % is the treatment column N from Fisher’s Exact Test cDenominator adjusted because gender-specific event for males: N=XX (Treatment 1), N=XX (Treatment 2) dDenominator adjusted because gender-specific event for females: N=XX (Treatment 1), N=XX (Treatment 2) bP-value 14 DRAFT 1 Table 7.3 Summary of Treatment-Emergent Adverse Events and Treatment Emergent Adverse Events Considered Related per Investigator by Preferred Term in Descending Frequency within System Organ Class Safety Population Treatment-Emergent Adverse Events Treatment Emergent Adverse Events Considered Related per Investigator Treatment 1 Treatment 2 Treatment 1 Treatment 2 System Organ Class (N = XX) (N = XX) (N = XX) (N = XX) Preferred Term n (%a) n (%a) n (%a) n (%a) P-valueb xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx [Preferred Term #1] xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx [Preferred Term #2]c xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx Number of subjects reporting P-valueb adverse events [System Organ Class #1] [System Organ Class #2] [Preferred Term #1]d …. aDenominator for each % is the treatment column N from Fisher’s Exact Test cDenominator adjusted because gender-specific event for males: N=XX (Treatment 1), N=XX (Treatment 2) dDenominator adjusted because gender-specific event for females: N=XX (Treatment 1), N=XX (Treatment 2) bP-value Preferred Terms within System Orqan Class are sorted in descending order of frequency based on the treatment-emergent adverse event category 15 DRAFT 1 Figure 7.1 Summary of Common Treatment-Emergent Adverse Events by Treatment 16 DRAFT 1 Table 7.4a Summary of Treatment-Emergent Adverse Events by Maximum Severity Safety Population Maximum Treatment 1 Treatment 2 (N = XX) (N = XX) n (%a) n (%a) P-valueb Preferred Term Grade Number of subjects reporting treatment- Mild xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) -- Moderate xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) -- Severe xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx Total xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx Mild xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) -- Moderate xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) -- Severe xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx Total xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx Mild xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) -- Moderate xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) -- Severe xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx Total xx (xx.) xx (xx.) xx emergent adverse events [System Organ Class Class #1] [Preferred Term #1] [Preferred Term #2] aDenominator for each % is the treatment column N from Fisher’s Exact Test cDenominator adjusted because gender-specific event for males: N=XX (Treatment 1), N=XX (Treatment 2) [For applicable PTs] dDenominator adjusted because gender-specific event for females: N=XX (Treatment 1), N=XX (Treatment 2) [For applicable PTs] bP-value 17 DRAFT 1 Table 7.4b Summary of Treatment-Emergent Adverse Events by Maximum CTCAE Grade Safety Population Maximum Treatment 1 Treatment 2 (N = XX) (N = XX) n (%a) n (%a) P-valueb Preferred Term CTCAE Grade Number of subjects reporting treatment- Grade ≥ 2 xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) -- Grade ≥ 3 xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx Grade ≥ 4 xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx Fatal xx(xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx Grade ≥ 2 xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) -- Grade ≥ 3 xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx Grade ≥ 4 xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx Fatal xx(xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx Grade ≥ 2 xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) -- Grade ≥ 3 xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx Grade ≥ 4 xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx Fatal xx(xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx emergent adverse events [System Organ Class Class #1] [Preferred Term #1] [Preferred Term #2] aDenominator for each % is the treatment column N from Fisher’s Exact Test cDenominator adjusted because gender-specific event for males: N=XX (Treatment 1), N=XX (Treatment 2) [For applicable PTs] dDenominator adjusted because gender-specific event for females: N=XX (Treatment 1), N=XX (Treatment 2) [For applicable PTs] bP-value 18 DRAFT 1 Listing 7.1 Listing of Treatment-Emergent Fatal Adverse Events by Treatment Group Safety Population Treatment = <<Treatment 1>> Subject ID Age Sex Race Date of First Date of Last Date of Preferred Verbatim Deemed Study Drug Study Drug Death Term of Fatal Term of Related to Administration Administration Event Fatal Event Treatment? (Study Day) (Study Day) 19 DRAFT 1 Table 7.5 Summary of Serious Adverse Events Safety Population Treatment 1 Treatment 2 (N = XX) (N = XX) n (%a) n (%a) P-valueb xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx [Preferred Term #1] xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx [Preferred Term #2] xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx Preferred Term Number of subjects reporting serious adverse events … aDenominator for each % is the treatment column N from Fisher’s Exact Test cDenominator adjusted because gender-specific event for males: N=XX (Treatment 1), N=XX (Treatment 2) [For applicable PTs] dDenominator adjusted because gender-specific event for females: N=XX (Treatment 1), N=XX (Treatment 2) [For applicable PTs] bP-value 20 DRAFT 1 Table 7.6 Summary of Adverse Events Leading to Treatment Discontinuation Safety Population Treatment 1 Treatment 2 (N = XX) (N = XX) n (%a) n (%a) P-valueb xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx [Preferred Term #1] xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx [Preferred Term #2] xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx Preferred Term Number of Subjects reporting adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation … aDenominator for each % is the treatment column N from Fisher’s Exact Test cDenominator adjusted because gender-specific event for males: N=XX (Treatment 1), N=XX (Treatment 2) [For applicable PTs] dDenominator adjusted because gender-specific event for females: N=XX (Treatment 1), N=XX (Treatment 2) [For applicable PTs] bP-value 21 DRAFT 1 Table 7.7a Summary of AESI Safety Population Treatment 1 Treatment 2 (N = XX) (N = XX) n (%a) n (%a) P-valueb xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx [Preferred Term #1] xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx [Preferred Term #2] xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx [Preferred Term #3] xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx [Preferred Term #n] xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx Preferred Term [Event Cluster] …… aDenominator bP-value for each % is the treatment column N from Fisher’s Exact Text 22 DRAFT 1 Table 7.7b Summary of AESI Safety Population Treatment 1 Treatment 2 (N = XX) (N = XX) n (%a) n (%a) P-valueb xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx [Preferred Term #1] xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx [Preferred Term #2] xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx [Preferred Term #n] xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx [Preferred Term #1] xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx [Preferred Term #2] xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx [Preferred Term #n] xx (xx.x) xx (xx.x) xx Preferred Term [Event Cluster] Broadly Defined Preferred Terms Narrowly Defined Preferred Terms …… aDenominator bP-value for each % is the treatment column N from Fisher’s Exact Text 23 DRAFT 1 7.2. Discussion There are certainly many ways to display adverse event data, and existing guidances vary in their recommendations and /or lack detail. Hopefully the recommendations in this white paper will provide added details to facilitate consistent implementation in clinical study reports and integrated summary documents. There was some debate as to whether an overview table (Table 7.1) should be recommended. The same information can be found in the other recommended tables, so it can be viewed as superfluous. However, since the structure of a clinical study report and integrated summary document includes a brief overview of adverse events, the overview table is recommended as something that can be included in the section. Otherwise, study teams may end up hand-generating such a table, which is unnecessary if deemed of value during analysis planning. The need for a summary of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) is consistently highlighted in guidance documents. We assume at least one display that includes all TEAEs is needed. Since guidance documents consistently highlight the need for a display of “common” TEAEs, we also assume a display for common TEAEs is needed. Since the guidance documents specifically say displays sorted by System Organ Class (SOC) are desired (e.g., the example table in the Reviewer Guidance), we assume at least one display sorted by SOC is needed. We also assume a display not sorted by SOC is desired to facilitate the identification of the most common TEAEs, which is typically outlined in the text of clinical study reports and integrated summary documents. With all these assumptions in mind, and with the desire to not over-burden study teams with creating a bunch of similar tables with essentially the same information, we recommend a table of all TEAEs sorted by SOC (Table 7.2) and a figure of common TEAEs not sorted by SOC (Figure 7.1). We considered a table that includes grouping MedDRA preferred terms by High Level Terms and System Organ Class (Table 12.1). We decided that the inclusion of High Level Terms is best used during interactive data reviews (out-of-scope) and/or topics of special interest (also out-of-scope). For purposes of clinical study reports and integrated summary documents, a table of preferred terms nested within SOC (Table 7.2) is recommended and consistent with the example table in the Reviewer Guidance. There was a fair amount of discussion related to a display of TEAEs considered related to study drug by the investigator. As noted in Section 6, we assume at least one reviewer from at least one regulatory agency would be interested in the data, which is why a display is recommended. The exact same display recommended for all TEAEs was strongly considered (with the added requirement to only include TEAEs considered releted to study drug by the investigator in the table), as it would be the easiest to implement and it reflects current practice across the industry. We also considered a display that would include all the different levels of relatedness, if multiple levels are included in collection (Table 12.2). However, since shared learning indicates at least one regulatory agency will expect a table that displays all TEAEs and TEAEs considered related to study drug side-by-side, Table 7.3 is recommended instead. We 1 DRAFT 1 don’t believe this table structure is currently implemented across the industry, but is now recommended based on shared learning. Regarding the display of TEAEs by severity (or CTCAE grade), a figure was considered (Figure 12.1). Although we are trying to move more toward visual displays, we decided that a table was better when displaying severity levels for all TEAEs. The figure can be utilized for topics of special interest if deemed useful. 2 DRAFT 1 8. Tables and Figures for Integrated Summaries 8.1. Recommended Displays [To be developed after receiving comments on Section 7] Consider TEAE – grouped PTs Consider exposure-adjusted TEAEs (for commone ones) 8.2. Discussion [To be developed after receiving comments on Section 7] 3 DRAFT 1 9. Example SAP Language 9.1. Individual Study [To be developed after Sections 7 and 8 are closer to final] 9.2. Integrated Summary [To be developed after Sections 7 and 8 are closer to final] 4 DRAFT 1 10. References Amit O, Heiberger RM, and Lane PW. Graphical approaches to the analysis of safety data from clinical trials. Pharmaceut. Statist. 2008; 7: 20–35. doi: 10.1002/pst.254. Crowe, B., Brueckner, A., Beasley, C., & Kulkarni, P. (2013). Current Practices, Challenges, and Statistical Issues With Product Safety Labeling. Statistics in Biopharmaceutical Research, 5(3), 180-193. Crowe BJ, Xia A, Berlin JA, Watson DJ, Shi H, Lin SL, et. al. Recommendations for safety planning, data collection, evaluation and reporting during drug, biologic and vaccine development: a report of the safety planning, evaluation, and reporting team. Clinical Trials 2009; 6: 430-440.. McGill R, Tukey JW, and Larsen WA. Variations of Box Plots. The American Statistician 1978; 32(1): 12-16. doi:10.2307/2683468.JSTOR 2683468. Nilsson ME and Koke SC. Defining treatment-emergent adverse events with the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities. Drug Information Journal 2001;35:1289-1299. Rosario LA, Kropp TJ, Wilson SE, Cooper CK. Join FDA/PhUSE Working Groups to help harness the power of computational science. Drug Information Journal 2012; 46: 523-524. The FDA/Industry/Academia Safety Graphics Working Group [Reference to be added] 5 DRAFT 1 11. Acknowledgements The key contributors include: xxxx. Additional contributors and members of the white paper project within the PhUSE Development of Standard Scripts for Analysis and Programming Working Group include: Acknowledgement to others who provided text for various sections, review comments, and/or participated in discussions related to methodology: . 6 DRAFT 1 12. Appendix Table 12.1 Treatment-Emerge Advserse Events – PTs nested within HLT Table 12.2 Treatment-Emergent Adverse Events by Relatedness Category (model after severity table – a way to show all the data when more than 2 categories are collected, but discarded due to shared learning expectations) Figure 12.1 Treatment Emergent Adverse Event by Maximum Severity 7 DRAFT 1 8 DRAFT 1 9