Anatomy of the Wasteland: Preface For the past five years I have

advertisement

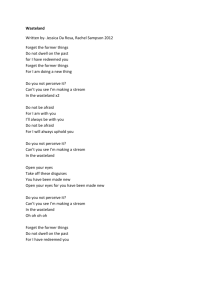

Anatomy of the Wasteland: Preface For the past five years I have tried to arrange my life so that I am away from my home in Australia during the December holidays. My aversion is not to family or Christmas gifts or glasses of New Year’s champagne, but to the quality of the time itself—the apathetic excess of it that seems eventually to dampen all activity. Dominated by a linear, Western ‘model of time’ that emphasises a Christian festival on the 25th December and the last day of the Gregorian calendar on the 31st (Griffiths 121, 183), I call this period the wasteland, during which people waste time or are laid to waste by it. Whether it is experienced physically or emotionally, the wasteland occurs before we realise how bound we are to the ‘practice of everyday life’ and (de Certeau), perhaps, how fearful we are of what lies beyond. Confronting because it marks a break in the conventions that prop up our lives, the wasteland may be experienced in different ways and even at different times. My title echoes T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land and Robert Burton’s The Anatomy of Melancholy; without conscious tribute to either text, the body of the poem may evoke the reference to sterility in the former—though in this case, December rather than April is ‘the cruellest month’ (Eliot st. 1)—and the emotional subject of the latter. More than just an emotive experience, the wasteland may also be a time of passive observation, in which regular action gives way to ‘watching’ and realising how little we understand ‘the silences, the gazes, the manner by which bodies speak’ (Sellars 55). It can also mean a break in continuity, a challenge to our everyday order, a reminder that life is not a (Western) drama of four or five acts. Sometimes it just drifts along; it may go one year after year without development, without climax, without definite beginnings or endings (Minh-ha 143). The wasteland can be a time for the empty present which, though it is normally ‘invisible to us’ now ‘saturates the total field of our environment’ (Minh-ha 143). The wasteland is therefore not a period of ‘dominant, chronological clock-time’ (Griffiths 22), but qualitative, kairological timing, which in sudden, frightening advent can shut one down to the opportunities it is said to provide (Griffiths 22). As Jay Griffiths explains, in kairological time ‘the future comes towards you...and recedes behind you while you may as well stay still, standing in the present—the only place which is ever really anyone's to stand in’ (22). Not only does standing still go against the chronologically-timed world of ‘getting and spending’ (Wordsworth), it also suggests the wasteland is a location on which to stand. The wasteland, as a place of ambiguity, has much in common with the ‘borderlands’ that Gloria Anzaldúa describes as ‘a vague and undetermined place created by...emotional residue...in a constant state of transition’ (25). As a time and a place, the wasteland is pervasive and thus has a complex anatomy to sketch. After Christmas 2011 and before the New Year of 2012, I toured my own wasteland in soporific suburban Adelaide and recorded the fragments I saw around me with a notebook and camera. My method was at first a spontaneous, uncalculated gathering, following ‘the moment of the instant, in what unfurls it’ when I ‘touch[ed] down then let myself slip into the depth of the instant itself’ (Cixous 104). Such instants, I am well aware, are irrevocably marked with the brand of capture as they are fixed on the page or in the lens, to be assimilated later into electronic or print form: grasping the present moment always involves altering the moment itself. This process of ‘destroying and saving’ (Minh-ha 132), however, 1 contributes to the theme of transition in time, in place and between language and image in new media poetics. As a new media poem, Anatomy of the Wasteland may be seen to deconstruct print poetry by adapting for digital presentation a narrative whose meaning relies, to a great extent, on the interaction between computer-generated text, images, format and mode of delivery. Since the poem remains ‘grounded in the materials which inscribe it’ (Burn 60), however, it is still language that aims to engage, causing readers to pause a little longer over each slide and become enmeshed in more than one layer of meaning. The piece thus belongs to a ‘field that is neither poetry nor not-poetry but an active exchange between [several] forms of discourse’ whose elements are ‘produced, distributed, archived, accessed, and/or assimilated on computers’ (Morris 19, 7). Its digital images allow ‘clicking, zooming, scanning, copying, cutting, pasting, sequencing, and…framing’ (Carter 15), and are open to the individual gazer who may then transform them into a site of ‘identity-construction’ (de Boeck and Plissart; Harrison; Rogoff 149). As I sorted my fragments into a sequence, I began interfering with the colours, emphasis and arrangement of both text and images in order to link them more strongly to my theme of the wasteland rather than solely to improve them. As such, I identify as a ‘snapshotter’ rather than a photographer (Slater), both in training and in spirit: Underlying “everyday” photography are models, socially derived, of the “takeable” photograph. This social dimension of “everyday” photography also ensures that the meanings of the images are in some measure available to everyone, drawing on shared values and systems of thought as well as aesthetic criteria. Personal image making draws on wider public narratives (Harrison 28). As a narrator who intends to make ‘meaningful, involving associations beyond what is captured and remembered, what is in the representation’ (Harrison 33), I find clarity is often more effective than abstraction. The text I chose to layer with the images is a prose poem, a narrative medium that again reflects the transitional state. Described by Kevin Brophy as occupying a ‘third way somewhere between prose and poetry,’ thereby ‘constantly [problematising] its nature, threatening to be one thing and refusing to be another’ (pars. 10, 15), prose poetry is well suited to the task of mapping the wasteland. Moreover, as it links the descriptive and the pragmatic, prose poetry reminds readers that ‘at least some aspects of what is portrayed are truthful to reality and do in fact physically exist’ (Suominen 32). Unlike the net of methodologies behind Anatomy of the Wasteland, my method of arranging the poem’s fragments can be summed up in one word: Powerpoint. While it does not involve the hypertext, code, high levels of interactivity, looping and networking that feature in more technologically complex new media poems (Kac 8), Anatomy of the Wasteland retains links to visual and kinetic design poetry with its more limited interactivity functions (Funkhouser). PowerPoint as a medium evokes corporate presentations with graphs and laser pointers, or chain emails with uplifting quotations set over pictures of majestic whales and sacred mountains. My prose poem fits somewhere within this continuum: in public screen presentation, it is timed and controlled by the performer but can also be widely distributed and accessible as an email attachment. Media, as Andrew Burn points out, are not ‘incidental to the making of meaning’ but carry a ‘semiotic burden, 2 always contribute to the meaning of the text’ (60); my choice of PowerPoint and use of features such as image ‘recolour’ and text box ‘shape’ may suggest to some readers aspects of the kitsch and, paradoxically for a poem that comments on the lapse of structured time, the corporate. The medium of PowerPoint does indeed ‘inscribe’ Anatomy of the Wasteland (Burn 60), though in a way that does not necessarily detract from its intent and even complements it. In keeping with Eduardo Kac’s statement that ‘[e]ach poet addresses his or her own themes through his or her own compositional system’ (8), it is not unintentional that the slides of the poem come across as naive, direct, stripped bare, with few devices to carry their textual meaning. Within the boundaries of PowerPoint, the construction of the poem is concentrated in details such as the distance or connection between the text and the images; the varying saturation of the photographs, reflecting the bleak light of the South Australian summer; the continuity achieved through the repetition of font colours and the black perforated line. Rather than narrowness, PowerPoint allows a directness of meaning, simplicity of presentation and ease of navigation that increases its appeal as a tool for everyday—even artistic—use. When individually navigated, Anatomy of the Wasteland is subject to the reader’s own sense of timing and understanding. Like Anniina Suominen, I invite ‘my readers to believe in my honest intentions of representing my experience[]’ of the wasteland but recognise that comprehension or non-comprehension, agreement or disagreement is ‘finally the decision each reader/viewer has to make’ with what s/he sees before her/him (32). In this sense, Anatomy of the Wasteland portrays transition as neither good nor bad, but as a time and a place that is possible to pilot as well as to drift through, and one that relies on personal timing to perpetuate or emerge from. [Photographic prose poem to be inserted—submitted as a separate file due to size] 3 Works Cited Anzaldúa, Gloria. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. 1987. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 1999. Print. Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida. 1980. Trans. R. Howard. New York: Hillary & Wang, 1981. Print. Brophy, Kevin. ‘The Prose Poem: A Short History, A Brief Reflection And A Dose Of The Real Thing.’ TEXT 6.1 (2002): n. pag. Web. 29 January 2012. Burn, Andrew. Making New Media: Creative Production and Digital Literacies. New York: Peter Lang, 2009. Print. Burton, Robert. ‘The Anatomy of Melancholy.’ Psyplexus. 25 February 2013. <http://www.psyplexus.com/burton/>. Carter, Paul. Material Thinking. Melbourne: Melbourne UP, 2003. Print. Cixous, Hélène. “Coming to Writing” And Other Essays. Ed. Deborah Jenson. Trans. Sarah Cornell, Deborah Jenson, Ann Liddle and Susan Sellars. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard UP, 1991. Print. de Boeck, Filip and Marie-Francoise Plissart. Kinshasa: Tales of the Invisible City. Amsterdam: Ludion, Tervuren/Vlaams Architectuurinstituut Vai, 2005. Print. de Certeau, Michel. The Practice of Everyday Life. Trans. Steven F. Rendall. Berkeley: U of California P, 1984. Print. Eliot, T. S. ‘The Waste Land.’ 2011. Bartleby.com. 25 February 2013. <http://www.bartleby.com/201/>. Funkhouser, Chris T. Prehistoric Digital Poetry: An Archeology of Forms, 1959–1995. Tuscaloosa: U of Alabama P, 2007. Print. Griffiths, Jay. Pip Pip: A Sideways Look At Time. London: Flamingo, 1999. Print. Harrison, Barbara. ‘Snap Happy: Toward A Sociology Of “Everyday” Photography.’ Studies in Qualitative Methodology 7 (2004): 23–39. Print. Isherwood, Christopher. Goodbye To Berlin. 1939. London: Vintage, 2003. Print. Kac, Eduardo. ‘Introduction.’ Media Poetry: An International Anthology. Ed. Eduardo Kac. Bristol: Intellect Books, 2007. 7–11. Print. Minh-ha, Trinh T. Woman, Native, Other: Writing Postcoloniality And Feminism. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1989. Print. 4 Morris, Adalaide. ‘New Media Poetics: As We May Think/How To Write.’ New Media Poetics: Contexts, Technotexts, and Theories. Ed. Adalaide Morris and Thomas Swiss. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2006. 1–46. Print. Rogoff, I. Terrra Infirma: Geography’s Visual Culture. New York: Routledge, 2000. Print. Sellars, Susan, ed. Hélène Cixous: White Ink: Interviews On Sex, Text And Politics. Stocksfield: Acumen, 2008. Print. Slater, D. ‘Consuming Kodak.’ Family Snaps: The Meaning Of Domestic Photography. Ed. J. Spence and P. Holland. London: Virago, 1991. 45–59. Print. Suominen, Anniina. ‘Writing With Photographs, Re-Constructing Self: An Arts-Based Autoethnographic Inquiry.’ Diss. Ohio State U, 2003. Print. Wordsworth, William. ‘The World Is Too Much With Us.’ 2011. Poetry Foundation. 29 January 2012. <http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/174833>. 5