A Community Engagement Framework for Health Partnerships

advertisement

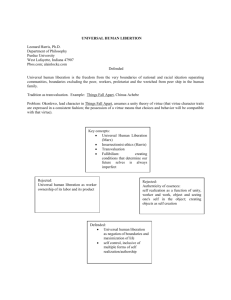

<run head>Working through Bound Liberation <run author>McDowell et al. <T>Working through Bound Liberation: A Community Engagement Framework for Health Partnerships <author>Tiffany L. McDowell, PhD1, Nataka Moore, PsyD1, and Juandalyn N. Holland, PsyD2 <info>(1) Adler School of Professional Psychology; (2) Teamwork Englewood <abstract subhead>Abstract <abstract>Background: A community–academic partnership was developed to implement a community-based participatory research project within Chicago’s Englewood community. Objectives: We explain how Mental Health Impact Assessment (MHIA) ensures that mental health and health inequities are considered in decision making by using a systematic process that engages populations most likely to be impacted by those decisions. Methods: We report on the process of developing an MHIA by engaging community partners to evaluate and predict potential mental health outcomes of an employment policy. Lessons Learned: We describe the principle of working through bound liberation, resulting in a bidirectional engagement between academics and community partners. We highlight lessons and challenges of our engagement process. Conclusions: Effectively joining in solidarity with community partners was critical for project success, but community capacity needs to be increased to support future projects. <abstract subhead>Keywords <abstract>Community-based participatory research, community health partnerships, health disparities, power sharing, process issues, <info>Submitted 14 January 2013, revised 6 May 2012, accepted 6 August 2013 1 <N>Englewood is a community on the Southside of Chicago with a variety of cultural, civic, and professional assets and organizations. In recent years, however, Englewood has been beset by many social and economic problems such as homelessness, unemployment, and violence, and broader challenges such as exclusion, racism, and inequitable distribution of income and wealth.1,2 A robust body of empirical evidence links these determinants to such poor mental health outcomes as anxiety, depression, and alcohol and drug abuse.3,4 Addressing sources of these social conditions may shift the focus from intervention to prevention to address the root causes as opposed to the symptoms of poor mental health.5 The sources of these social conditions are often rooted in policies, planning projects, and other public decisions, which can have significant impacts on the physical and mental health of communities, particularly for vulnerable populations.6,7 An MHIA is a Health Impact Assessment that focuses explicitly on the mental health implications of public decisions. MHIA is a valuable tool for stimulating the development of socially just policies and proposals that robustly and transparently consider and manage the multiple ways in which communities are affected.8 MHIA assesses the potential impacts public proposals (e.g., laws, policies, programs, or projects) have on the social determinants of health and mental health, that is, where people are "born, grow, live, work, and age.”7 MHIA uses a systematic process to evaluate positive and negative impacts of potential policies and proposals on health equity. A balance must be struck between securing the greatest health gain for the population as a whole, and protecting and promoting the health of marginalized groups. Integral to the success of MHIA is community engagement and capacity building, so that community input informs potential policy recommendations and ongoing monitoring of future physical and mental health outcomes. The remainder of this paper describes the background and process of MHIA, including development 2 of research procedures and recruitment strategies. We also highlight our overarching frame of community engagement rooted in strong partnerships based in solidarity. <A>MHIA <N>MHIA, conceived by researchers and faculty at the Adler School of Professional Psychology, grows out of established Health Impact Assessment practice, but advances the practice in two ways. First, it expands the practice beyond its traditional focus on physical health to include a focus on mental health. Second, it moves beyond assessment of planning, land use, and built environment proposals (e.g., zoning changes; residential, commercial, and transportation projects) to include a broader range of proposals (e.g., labor, education, social welfare, and public safety) relevant to the needs of disadvantaged communities. Thus, the MHIA provides new information and a new frame (i.e., mental health impacts) by which to determine whether or not a proposed policy, program, or project should be implemented. Similar to Health Impact Assessment,9 MHIA methodology involves six specific steps: 1) Screening determines whether a proposal is likely to have mental health effects and whether the MHIA will provide information useful to the stakeholders and decision makers; 2) scoping establishes the potential mental health effects that will be assessed in the MHIA, the populations affected, members of the MHIA team, sources of data, methods to be used, and alternatives to be considered; 3) assessment involves a two-step process that first describes the baseline health status of the affected population and then assesses potential impacts; 4) recommendations suggest alternatives to the policy or proposal that could be implemented to improve health or actions that could be taken to manage the health effects, if any, that are identified; 5) reporting presents the findings and recommendations to stakeholders and decision makers; and 6) monitoring and evaluation tracks the adoption and implementation of MHIA recommendations 3 and following the changes in health or health determinants. Authentic efforts to partner with a community can be time consuming but well worth the investment to maintain community interest and engagement in the MHIA process. The project team wanted to ensure that the policy at the center of the MHIA was relevant to the Englewood community and reflective of resident concerns. Often, researchers approach community members with rigidly defined goals and objectives, leaving little room for community input. Applying community-based participatory research within the MHIA process allowed for shared power and responsibility among partners.8 The authors of this paper include two researchers from the Adler School and the Executive Director of Teamwork Englewood, the primary community partner on this project. We chose to form a writing team to accurately describe our partnership with one another. <B>Bound Liberation <N>The key component of the MHIA process was to be very purposeful in engagement to counter the negative perceptions of research in a community where residents have noted that past academic partnerships have been challenging. Community residents perceived that the unclear motives of previous researchers and their lack of relationship building with the community as genuine partners have resulted in tenuous relationships. Aware of this, the authors practiced the concept of bound liberation to foster development of a mutually beneficial relationship. <quote> If you have come here to help me, you are wasting your time. But if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together. (Lilla Watson, Aboriginal Woman) <N>This quote exemplified our principles for working within the community for the MHIA project. As African-American females, we understood our liberation, health, and pursuit of social justice were irrevocably intermingled with the predominantly African-American community of 4 Englewood. This concept is deeply rooted within Black Feminist theory, which maintains that liberation of an individual cannot occur until all oppression is eliminated.10 Stakeholder and resident engagement followed a process that aligned with this guiding principle: Work through bound liberation. All three authors have been trained in psychology and family systems, so we understood the importance of “joining” or engaging with the members of the community in solidarity toward eradicating oppression. Adapted from structural family therapy,11 the process of joining includes being accepted by the community and remaining in that position throughout the partnership. As we moved through the six steps of the MHIA, we developed strong relationships based in bound liberation, because our overarching goal throughout the project was to become invested members of the community. We achieved this goal through three primary strategies. First, we actively participated in various community events outside the scope of the MHIA project, such as community cleanups, health fairs, town hall meetings, and movie nights, which demonstrated that we were committed to the community needs beyond the research. Additionally, the authors consistently used the words “we” and “our” in community settings. For example, at a town hall meeting, the authors would say, “We need to advocate for ourselves in addressing school closures.” As we discuss working in bound liberation, “we” in this paper describes not only the three authors, but all community partners, residents, stakeholders, and participants. Finally, the authors shared their activism in their residential communities, and the shared linkages between their communities and Englewood, such as the commitment toward improving school systems and increasing employability for residents in the respective neighborhoods. In the end, this showed Englewood residents that we really were all connected in fighting injustices that worsen health inequities. 5 <B>MHIA Methods <N>In January 2011, the Adler School of Professional Psychology received funding from Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, W.K. Kellogg Foundation, and the Pierce Family Foundation to conduct an MHIA in the Englewood community to inform the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission of potential mental health impacts of the proposed revisions to the Policy Guidance on Consideration of Arrest and Conviction Records in Employment Decisions Under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.8 Figure 1 details the research hypothesis of the project. The pathway diagram illustrates hypothesized relationships between the proposed revisions and four key social determinants of interest: Social exclusion, employment, income, and neighborhood conditions. Anticipated changes in the social determinants were hypothesized to have important impacts on both individual-level and community-level mental health outcomes. Arrows on the pathway diagram indicate relationships between the policy, social determinants, and mental health outcomes. <T>ADD FIGURE 1 ABOUT HERE <N> The Adler School was able to begin this work through the 6-year relationship with Teamwork Englewood, an organization formed in 2003 to serve as a vehicle for bringing together residents, organizations, churches, and businesses in the community. Teamwork Englewood, serving as lead community partner and subcontractor on the grant awards, assisted with convening other community partners to join the project team. Partners included Imagine Englewood IF, Resident Association of Greater Englewood (R.A.G.E.), Kennedy-King City College of Chicago, Expanded Anti-Violence Initiative (E.A.V.I.), Greater Englewood Block Club Coalition, St. Bernard Hospital, Cure Violence (formerly CeaseFire Chicago), and the U.S. Bank-Englewood Branch. Through this partnership, the project team recruited more than 450 6 community residents, employers, police officers, and policymakers to participate in the town hall meetings, focus groups, and surveys over the course of the project. This research project was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Adler School for the protection of human subjects. During the Screening step, which is to screen for proposed policies that may have mental health impacts on a community, we engaged in a series of conversations to assess community strengths and challenges. For example, we used structured formats such as focus groups and individual interviews to determine top priorities. However, we also used informal means such as casual conversations with residents and stakeholders while participating in community events and activities. Other organizations began to come to the table as they saw our alignment with their goals. For our work to be bound to theirs, we along with several other community organizations became a coalition of residents, students, politicians, and community organizers where the MHIA became one of the collective strategies to improve neighborhood conditions. The coalition gave credibility from community members’ perspectives to the MHIA project. The coalition then developed a list of 62 potential policies addressing youth, violence, housing, and employment issues. The coalition identified the EEOC policy as it addressed many of the top priorities of the Englewood community. Because the goal of the Scoping step is to outline research questions, community partners held focus groups to define the parameters of the project. Because the policy involved employer use of arrest records in making employment decisions, we were interested in understanding how the amendment would impact young people in the community. “Resident-scientists” were trained to conduct interviews with young people who were difficult to access—those who would be least likely to participate in focus groups or surveys. In the Assessment step, the coalition of partners 7 assisted in the recruitment of participants for survey, focus group, and interview data collection. The Adler School shared a portion of project grant funding with Teamwork Englewood to hire a resident to administratively support both the MHIA and Teamwork Englewood projects. To communicate findings to Englewood residents, three town hall meetings were facilitated by community partners for feedback on preliminary results, formulation of recommendations, and reporting project outcomes. Teamwork Englewood consistently updated the Englewood Portal website with MHIA project announcements and events. To maintain partnerships developed with the coalition, we are currently implementing a year-long Monitoring and Evaluation process in which community partners are trained to track mental health and social determinants impacts of the policy. An overriding goal of this work will be to equip Englewood residents with the knowledge, skills, and tools required promote the health and well-being of children and families, including capacity for monitoring, civic engagement, and participation in public decision-making processes that stand to impact their health. <A>Lessons Learned <N>One of the fundamental lessons learned was that, for a community that had long been excluded from public decision-making processes, partnership development had to be very authentic and purposeful. The first two authors observed that, through using a bound liberation approach, the level of engagement shifted beyond simple research partnership to one of mutual respect and ownership of project targets and outcomes. Over the course of several months, a bidirectional process of engagement took place. The community was open to the first two authors joining, not just because of similar demographic backgrounds, but because of the solidarity on community issues through bound liberation. As a leader of an influential 8 organization within Englewood, the third author on this paper noted that previous researchers have exploited partnerships by making data inaccessible or by creating undue competition for resources among community organizations. However, owing to our bound liberation, she views our partnership more as a sisterhood, associated with joining as a family, where she felt comfortable having mutually beneficial dialogue and shared leadership. She credited this as a model for the community to observe and learn from to build capacity to work in partnership with academic institutions in the future. The MHIA provided an opportunity to engage Englewood residents and partners in a project with meaningful, shared goals. Through observation and feedback from partners, we learned that capacity-building processes need to be incorporated early in the project timeline. Joining was critical to project success, but now that we are at the end of the MHIA process, we face the difficult task of transferring primary responsibility of managing ongoing project goals to the community. Englewood residents developed skills and tools during the course of the project; however, these tools need to be strengthened to continue the work now that this phase of the project is complete. This may be challenging because this project may have appeared nuanced to community residents and they may find it difficult to find ways to strengthen and translate their new tools for future initiatives within their community. The challenge of transferring skills to residents was not a particular aspect the coalition considered when moving through the process; however, as we transition into Monitoring and Evaluation, we will plan activities to ensure that residents will understand how to apply this skill set for addressing other community issues. Although joining with a community is a valuable means of supporting involvement, project plans should include strategies for community-engaged researchers to encourage community members to take the lead in achieving their research aims. 9 <A>Conclusions <N>Community-based participatory research is a collaborative approach to research allows researchers to adapt best practices to the community's needs.12 Researchers often require a conduit to engage community partners, and view engagement as inviting community to the table to achieve project goals. In vulnerable communities, stakeholders may reasonably question what motivation researchers have in the partnership. Working through bound liberation extends the historical community-based participatory research practice of transforming power dynamics toward the promotion of social change in community health partnerships.13 It requires academic partners to align with the larger goals of the community, versus prioritizing research objectives or professional agendas. This approach can repair community–academic relationships in vulnerable communities owing to potential mistrust of researchers. In establishing a bound liberation framework, future researchers and community partners should be mindful of creating a space where all partners can generate shared goals. All partners should be encouraged to participate in initiatives beyond the scope of the research to be fully invested in community needs. Therefore, this concept should extend even after the research project is over. Critical to project success is a sharing of resources so that the community considers the partnership to be equitable. Ultimately, the community needs to know that research partners are connected and working in solidarity. <A>Acknowledgments <N>The authors acknowledge the entire Mental Health Impact Assessment project team, including community partners Teamwork Englewood, Imagine Englewood If, Resident Association of Greater Englewood, and Cure Violence (formerly Ceasefire Chicago). Support for 10 this project was provided by funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, W.K. Kellogg Foundation, and Pierce Family Foundation. <A>References 1. Yonek J, Hasnain-Wynia R. A profile of health and health resources within Chicago’s 77 communities. Chicago: Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Center for Healthcare Equity/Institute for Healthcare Studies; 2011. 2. Bocskay KA, Harper-Jemison DM, Gibbs KP, Weaver K, Thomas SD. Community area health inventory part two: Community area comparisons. Health Status Index Series, Vol. XVI No. VI. Chicago: Chicago Department of Public Health Office of Epidemiology; 2007. 3. Kloos B, Shah S. A social ecological approach to investigating relationships between housing and adaptive functioning for persons with serious mental illness. Am J Community Psychol. 2009;44:316-26. 4. Scutella R, Wooden M. The effects of household joblessness on mental health. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67:88-100. 5. Moore N, Link M, McDowell T. Social determinants to health: Youth in U.S. based armed groups and child soldiers. Intl J Humanities Soc Sci. 2013;3(2):49-52. 6. Todman L. The social determinants of mental health. The SES indicator. Washington (DC): American Psychological Association; 2011. 7. Marmot M, Friel S, Bell R, Houweling TA, Taylor S; Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Lancet. 2008;372(9650):1661-9. 11 8. Adler School of Professional Psychology, Institute on Social Exclusion. U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission policy guidance: A mental health impact assessment. Chicago: Adler School of Professional Psychology; 2013. 9. North American HIA Practice Standards Working Group. Minimum elements and practice standards for health impact assessment. Oakland (CA): North American HIA Practice Standards Working Group; 2010. Available from: http://www.humanimpact.org/doclib/finish/11/9 10. Collins PH. Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge; 2000. 11. Minuchin S. Families and family therapy. Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press; 1974. 12. Altman DG. Sustaining interventions in community systems: on the relationship between researchers and communities. Health Psychol. 1995;14(6):526–36. 13. Wallerstein N, Duran B. The theoretical, historical, and practice roots of CBPR. In: Community-based participatory research for health: From process to outcomes. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2008. p. 25-46. 12 <table number>Figure 1. <table title>Hypothesized relationships between policy decision, social determinants, and mental health. EEOC, Equal Opportunity Employment Commission. 13