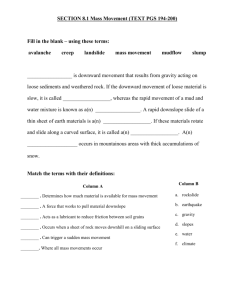

NSW gov Dunal management

5.2.3 Dune Management

Dune management is the combination of activities that aim to sustain the role and value of beach dunes. Management for a stable dune system involves the control of windblown sand when it encounters the foredune. The elevated foredune interacting with zoned vegetation is recognised as one of the basic requirements for coastal stability.

(see Appendix B8 ).

The basic principle in dune management is to maintain a satisfactory vegetative cover on the foredune. This prevents sand blowing inland where it is lost from the coastal system.

Management of coastal dunes involves the application of land capability principles, organisation of recreational activity and rehabilitation of disturbed dunes.

Dune management options are described briefly below, and in more detail in Appendix D5 .

Detailed information on dune management techniques is provided in the Soil Conservation

Service's "Coastal Dune Management" manual.

(a) Dune Management Planning

Before any management or rehabilitation program is undertaken, certain information must be obtained so that a suitable program can be developed. Investigation of the land resource, land use patterns and planning of management programs should be undertaken well before any actual works commence. A detailed treatment of dune management planning is provided in the following reference: "Coastal Dunes of New South Wales,

Status and Management", D.M. Chapman, University of Sydney Coastal Studies Unit

Technical Report No. 89/3.

(b) Community Involvement

Measures designed to influence peoples' awareness of, their attitude to, and their physical impact on the beach system are an integral part of a successful dune management program.

The dilemma facing the coastal manager is that although dunes are an extremely fragile landform not well adapted to community pressure, they are a popular resource.

Australians are largely coastal dwellers and traditional beach users. This beach usage has been intensified in recent years as traditional beach activities have been added to by newer recreational, residential, and tourist development.

To be most successful, dune management programs require the community to be aware of, and actively or passively support, dune management works.

(c) Dune Reconstruction

Any revegetation program implemented on coastal dunes requires a suitable landform for the planting of grasses, shrubs and trees. A suitable landform is essentially an area of sand with no major hummocks or undulations which will interrupt wind flow and cause the wind to concentrate, making vegetation establishment difficult or even impossible.

Preparing such landforms generally involves the reforming of dunes. This may involve filling of small blowouts, or on a larger scale, the reconstruction of hundreds of metres of dune.

(d) Dune Revegetation

The major objective of any dune revegetation program should be to provide sufficient plant cover to protect against wind erosion. Species native to the coastal dune system have adapted to survive the hostile environment of drifting sand, strong winds, salt spray and infertile soils, and provide long term stability to the system.

A successful revegetation program will also provide other benefits to the coastal system including increased protection for landward areas and amenities, improved habitat for native fauna, particularly birds, and enhanced beach amenity.

Figure 5.2 Dune Stablisation, Newport Beach, Sydney.

(e) Dune Protection

The provision of dune protection is necessary where land use pressures will, in the absence of protection measures, cause damage to the dune landform or vegetation. A combination of dune fencing, formalised accessways and signposting is normally used to protect the dune system. An active community awareness program will complement these measures.

Fences preserve both revegetated and naturally vegetated areas by protecting them from uncontrolled pedestrian and vehicle traffic. Formalised accessways allow pedestrians and vehicles access to dunes in a manner which protects both the dune and adjoining vegetation; they are fenced to direct and confine the movement of the traffic; and the dune surface is generally protected by materials such as board and chain mats to prevent sand blowing from the accessway and to provide traction for traffic.

(f) Dune Maintenance

Both rehabilitated and natural dune areas require long term maintenance (maintenance in perpetuity), to ensure that vegetation and structures such as fences and accessways retain their function, and to protect the initial investment of funds in management works.

Deterioration of rehabilitation works may be caused naturally by the action of the wind, waves and moving sand. Vandalism may increase the rate of deterioration of works.

Maintenance of dune management works includes the following aspects:

continuation of public awareness campaigns;

repairs to fences, accessways and signs; replanting of areas where plants have failed to establish or have died because of disease, insect attack, fire or moisture stress;

planting of secondary and tertiary vegetation in suitable areas;

control of weeds such as bitou bush and lantana;

application of fertiliser when required; and

fire control.

Figure 5.3 Seawall and Promenade, North Steyne, Sydney.

Consistent and adequate maintenance of rehabilitation works will contribute to the aesthetic appeal and amenity of the beach area. Regular maintenance will also reduce the need for major restoration at a later date, thereby reducing the cost of subsequent works.

5.2.4 Protective Works

Protective works are described in detail in Appendix D6 .

In general, protective works tend to be expensive. However, they often provide the only socially and economically acceptable means of reducing hazards to existing properties at risk. Unless carefully designed and constructed, structural works, by reason of their location within the active beach zone, may have a number of unforeseen detrimental effects on amenity.

(a) Seawalls

A properly designed and constructed seawall will protect properties and areas of the foreshore from the impacts of beach erosion and coastline recession hazards. However, the recreational use and scenic appeal of the beach may be reduced by seawalls, especially if their presence facilitates the loss of sand in front of the wall and/or delays beach rebuilding after storms.

(b) Training Walls

Properly designed and constructed training walls can stabilise a coastal entrance, improve navigation and help mitigate estuarine flooding. However, training walls can markedly alter patterns of erosion and deposition, both within the estuary and on the coastline either side of the entrance. They can also have a marked effect on the tidal range of the estuary and thereby estuarine ecology.

(c) Groynes

Groynes can provide coastal protection and increase amenity by building a wider beach.

However, erosion tends to occur along the section of beach downdrift of the groyne field.

This can be minimised by initially filling the groyne embayments with sand as part of a beach nourishment program.

Figure 5.4 Groyne Structure, Kirra Beach Qld.

(d) Beach Nourishment

Like groynes, beach nourishment provides coastal protection and increases beach amenity by building a wider beach. However, unlike groynes, nourishment does not promote erosion in downdrift locations of the beach. In fact, beach nourishment programs have few if any detrimental effects (this is part of their attraction) provided that an adequate supply of suitable sand is available and that it can be obtained without undue consequences. One potential drawback of beach nourishment is that further nourishments may be needed in the future.

(e) Offshore Breakwaters

Offshore breakwaters reduce the intensity of wave action in inshore waters and thereby reduce coastal erosion. They have not been commonly used along the New South Wales coast. They are costly to construct because of the prevailing wave climate and their use is generally limited to the protection of sheltered areas not exposed to open coast wave conditions.

(f) Artificial Headlands

Artificial headlands act as large groynes that extend into deep water to restrict longshore transport. On the open coast, they require large, expensive structures. Consequently, their use has been restricted to areas with less severe wave climates.

(g) Configuration Dredging

Configuration dredging is dredging to a pattern such that wave refraction limits the effects of wave action on a stretch of coastline. Its usefulness on the open coast is restricted by the variety of wave directions possible and the scale and cost of works required. It may have application in more sheltered waters but could only be considered where the coastline processes were well understood.