Aristotle

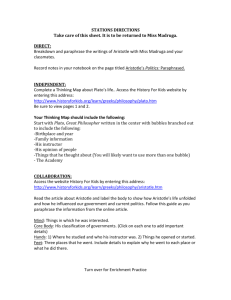

advertisement

Aristotle (384 – 324 BC) – Poetics The disciple of Plato. Plato’s name not even mentioned in his Poetics. The tutor of Alexander the Great. T.S. Eliot calls him “a perfect critic”. Saintsbury hails him “the very Alexander of criticism”. His works are his lecture notes. Why is it said that Aristotle’s works are ‘acromatic’ in nature? Aristotle’s works are considered acromatic in nature because each work of his cannot be completely understood without the help of his other works. For example, knowledge of his Ethics, Metaphysics and Rhetoric would throw greater light on Poetics. What are the reasons for the difficulty in understanding Aristotle? His works are only lecture notes gathered by his students and not a full-fledged treatise. Moreover, his works are esoteric in nature, meant for a chosen and initiated group who may not need lengthy explanations. The major terms discussed by Aristotle in his Poetics are: Mimesis: Mimesis means imitation. There is a major difference between Plato’s theory of imitation and Aristotle’s theory of imitation. The Platonic view is that the world is an imperfect reflection of an ideal archetypal order. Poetry, being an imitation of an imitation, is thrice removed from reality. However, Aristotle rejects Plato’s doctrine of ideas. For Plato imitation means copying, whereas for Aristotle it is creative and dynamic. It is representation and not just copying that Aristotle has in mind, not a representation of men as they are. The artist imitates things as they ought to be, and so, art is a free and voluntary activity of the human consciousness, free from any utilitarian motives. We derive pleasure from the artistic representations of even the most repelling of things. We see into the life of things. Imitation leads us from the particular to the universal. Art is a source of insight into life. For Aristotle mimesis does not mean photographic reproduction. Rather, it means a recreation of inner human action. Katharsis: This is a key word in Aristotle, occurring only twice in Poetics. In chapter six, Aristotle defines tragedy as “the imitation of an action that is serious, complete in itself and of a certain magnitude, in an embellished language, through action and not through narration, and through pity and fear effecting the katharsis of these emotions”. Pity and fear constitute the two-fold audience reaction to the sight of tragic suffering. Pity and fear demand the tragic hero to be noble; only then his fall from happiness to misery arouses in us these emotions. Pity is aroused by the magnitude of the suffering undergone by the protagonist. Terror is aroused by the knowledge that tragic suffering and fate has overtaken one similar to us. The meaning of the term has given rise to a lot of controversy. The four meanings of Katharsis are: 1. The Therapeutic (Purgation): It is akin to the homoeopathic system of medicine that holds the view that the right cure for an illness is administering an agent similar to the disease. In this sense Katharsis means purgation. It means that by presenting the emotions of pity and fear to the audience, the audience is cured of the excesses of these emotions. Tragedy effects Katharsis by generating the very conditions that it seeks to cure. But many scholars do not accept this medical metaphor. 2. The Moral (Purification): The purpose of tragedy is to purify the emotions of the audience by disciplining it, and refining it by removing the excesses. Understood as a religious metaphor, Katharsis means purification. It is paradoxical that we go the theatre to experience delight from the spectacle of suffering. However, it must be realized that the element of external suffering on the stage is perhaps the least important part of the tragedy. True tragedy unfolds an inner process. We find the protagonist in a state of clash at three levels – with oneself, with others, and with the impersonal forces of nature. In this three-dimensional conflict, the protagonist displays a certain dignity and probity. The apparent destruction of virtue and innocence may strike terror. But ultimately we realize that the good and the virtuous may be destroyed, but the values of goodness and virtue remain sound and secure. The moral foundation may be shaken, but it only becomes stronger and deeper. F.L. Lucas remarks “the theatre is not a hospital”. However, many scholars do not accept this view of art as a moralizing agent. 3. The Structural (Absolution): It views Katharsis as a process by which the protagonist can absolve himself of the supposed evils he has perpetrated, so that the audience can respond with emotions of pity and fear appropriate for the occasion and be willing to free the protagonist from pollution. 4. The Intellectual (Clarification): Katharsis is a kind of insight experience. The features of this experience are It is pleasurable and not painful as in real life This pleasure is similar to that arising from learning It leads to clarification According to Aristotle, the character of a wise, virtuous man is that he feels emotions at the right time, with reference to the right people, the right object, with the right motive and in the right way. This is the principle of moderation. Katharsis obeys and conforms to this principle. The result of Katharsis is emotional equilibrium. It involves restoration of emotional health. Whichever meaning one may support, Aristotle sees art not as being harmful as Plato does, but as being beneficial. Hamartia: Hamartia means tragic flaw. The protagonist commits a moral error, and for this, he receives his punishment. This view has been modified to relate the term to an intellectual rather than a moral error. For instance, a character who has distinguished himself in one sphere is thrown into a different sphere of action. Tragic flaw results in his exercise of his value system in the new sphere in which it does not hold good. Shakespeare’s tragic heroes are an instance in point. Brutus comes to grief by imposing the ethical on the political. Again, the tragic flaw occurs when King Lear applies the laws that operate in the feudal world to the family by demanding a profession of love from his daughters. Spoudaios: It means noble character. For Aristotle, character is what determines moral choice. Tragedy imitates noble character, and comedy base character. Critics like Arthur Miller mistake character as socially determined and hence accuses Aristotle of social arrogance and snobbishness. Aristotle never ever said that a common man cannot be a tragic hero. Miller fails to grasp the basics in Aristotle’s logic. The nobility referred to in Poetics is morally determined and not socially construed. The Poetics The elements of a tragedy are: plot, character, thought, diction spectacle and song. Plot is morally determinate action. Though the external events are the same, the plot of Romeo and Juliet is tragic, while that of ‘Pyramus and Thisbe’ in A Midsummer Night’s Dream is farcical. Plot is the soul of tragedy. It is the shaping principle that gives unity to a work. Character is that which reveals moral purpose. Probable impossibilities are to be preferred over improbable possibilities. Anagnorisis means recognition and peripeteia means reversal of fortune. A work of art resembles a living organism; it has a beginning, middle and an end. Aristotle was never a dogmatic, prescriptive critic. He only described what he saw in the drama of his time. Robertello and Castelvetro misread Aristotle’s theory of the three Unities. It was Dr Johnson who rectified this error. Aristotle prescribed only the Unity of Action by which is meant the action must be organic. Unity of Time and Unity of Place were later Renaissance additions. The Romantics were against Aristotle. The Poetics is unbelievably short. It has only 26 chapters. The first five are introductory chapters, the next fourteen chapters are devoted to tragedy, the next eight, diction, and the next four on the epic, and the very last one deals with problems in criticism. Lyric poetry is completely ignored, and the epic and the comedy are given only sketchy treatment.