Chapter 3 Methods in Corpus Linguitics

advertisement

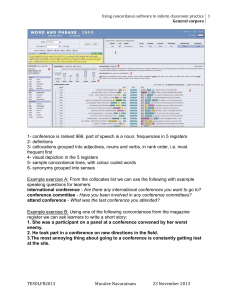

Chapter 3: Methods in corpus linguistics: Interpreting concordance lines (Hunston, Susan. Corpora in Applied Linguistics. CUP, 2002) 3.1 Introduction This chapter offers a number of examples of corpus searches, each one illustrating one or more points about the methodology of finding and interpreting concordance lines, and about the kind of findings that emerge from such study. ‘word-based’ methods cf.) ‘category-based’ methods (chapter 4) The topics in this chapter ・What kind of searches are useful in finding out about how English works? ・How can concordance lines be presented in an accessible way? ・What are concordance lines useful for? ・What view of language does this chapter want to put across? And What general assumptions about language investigation are made in offering concordance lines as a source of information? 3.2 Searches, concordance lines and their presentation A concordancer is a program that searches a corpus for a selected word or phrase and presents every instance of that word or phrase in the centre of the computer screen, with the words that come before and after it to the left and right. a node word = a selected word, appearing in the centre of the screen Sort lines to make them more visible The words focused on are printed bold. e.g.) critical ・ (be, is) critical, (a, his, this) + critical + (noun), self-critical ・ be critical of … ‘negative opinion’ ・ be critical to, be critical in … ‘important’ ・ critical + (noun) … ‘important’ ・ more predicative use than attributive use Search for a phrase, or for specific word-classes e.g.) on + adjective + terms + with a degree of closeness (familiar, friendly, intimate), whether or not the two groups like each other (good, reasonable, bad) a similarity in status (equal) 3.3 What is observable from concordance lines? 3.3.1 Observing the ‘central and typical’ Linguistic description focuses on distinctions between what ‘can’ and ‘cannot’ be said in a particular language, with little regard for whether what is possible frequently or rarely occurs in practice. (Swan) There is no ‘demarcation’ between the correct and the incorrect. In place of demarcation, a corpus offers information that a native speaker cannot replicate: an indication of ‘central and typical’ usage. (Hanks, Sinclair) ’Typical’ is used to describe the most frequent meanings or collocates or phraseology of an individual word or phrase. e.g.) recipe for ・more metaphorical meaning than literal meaning ・recipe for + N which has a negative meaning ・BE + a + recipe for ↓ typical use: something is a recipe for something bad The concept of ‘centrality’ applied to categories of things rather than to individual words. e.g.) central use of present progressive: the reference to present time a central adjective: an adjective which occurs both attributively and predicatively Native speakers’ intuitions about typicality do not always accord with evidence of frequency. Prototypical: a usage which is commonly felt to be typical but which is not necessarily most frequent. (Barlow and Shortall) ・English teaching course books e.g.) comparatives (course book) The USSR is larger than China. (corpus) a larger plan, their larger but poorer northern neighbours comparison is implicit e.g.) reflexive pronouns (course book) be proud of oneself, be proud of one’s child (corpus) FIND + oneself, SEE, IMAGINE, VISUALISE, CONSIDER, ASK + oneself indicating thoughts and speech > the verbs of physical action I saw myself in the mirror. > He hit himself with the hammer. The psychologically prototypical is not necessarily to be ignored in language teaching, but knowing what is central and typical in frequency term can indicate what the bulk of examples that a learner is exposed to should be like. The notion of typicality will be related to the idiom principle and to the reduction of ambiguity. e.g.) Time flies. ‘we perceive time to pass quickly’ > ‘use a stop-watch to time how quickly flies move’ 3.3.2 Observing meaning distinctions Observing typical usages of near-synonyms can clarify differences in meaning. Study on ‘semi-grammatical’ words (words which by themselves carry only a general meaning) (Partignton) e.g.) sheer, pure, complete, utter, absolute sheer: ・with nouns of degree or magnitude, often in the pattern of the sheer N of N(sheer number, the sheer weight of noise) ・in expressions indicating causality (through sheer insistence) absolute: with ‘hyperbolic’ nouns (chaos, disgrace) 3.3.3 Observing meaning and pattern The meaning of words are distinguished by the patterns or phraseologies in which they typically occur. To illustrate this, it is common to divide concordance lines into set, each set exemplifying one meaning. e.g.) initiative Set 1: an initiative, a government initiative ‘something that someone ( usually a government agency or other institution) starts to try to solve a problem’ Set 2: take the initiative ‘start something and so gain an advantage over a competitor’ lose the initiative: ‘fail to start something and so allow a competitor to gain an advantage’ Set 3: ‘a lot of initiative the quality of being able to do things without being told’ e.g.) CONDEMN condemn something , condemn something as something ‘criticize’ condemn someone to something ‘make something bad happen’ ‘pass sentence’ condemn someone to do something (be condemned to do something) ‘something’ is bad or undesirable Words with similar meaning tend to share patterns e.g.) it + BE + adjective + that-clause The adjectives which indicate an evaluation or judgement. Judgements of likelihood (inevitable, likely, possible, unlikely) clarity (apparent, clear, obvious) necessity (crucial, essential, important, necessary) significance (revealing, significant) goodness or badness (appropriate, fitting, etc.) other kinds of judgement ( ironic, surprising, etc.) ‘frames’: sequences of, usually, three words in which the first and last are fixed but the middle word is not e.g.) a …of, be …to The frame has a numerical significance to the corpus which far outweighs the significance of any one of the triplets. Renouf and Sinclair’s corpus: a … of: 3,830 a lot of:1,322 a quarter of: 174 The frame is significant to each word which occurs as the middle item in it. The middle words belong to particular meaning groups. e.g.) many … of thousands, kinds, years, members: numbers, a type or aspect, a length of time, a group of people or thing Why are ‘frames’ useful? ・ Frames are useful because programs can be written to identify them automatically, without the researcher knowing or guessing in advance what they will be. ・ Frames show part of what is typical in a corpus and, because they incorporate variation, they are much more frequent than fixed phrases are. ・ Frames and patterns are an alternative to the very general statements made by most grammars and the very specific statements that can be made about the collocations of each individual word in a language. ・ Frames are particularly useful when looking at a specialized corpus, and can be used as the basis for investigating the language of a discipline. 3.3.4 Observing detail For more specific observations about the behaviour of individual words, it is necessary to obtain more co-text. e.g.) V + advice as to ( + wh-clause) a verb indicating ‘getting, giving, wanting or offering’ e.g.) V + ANSWER as to (+ wh-clause) ・a verb indicating ‘getting, giving, wanting or offering’ ・ANSWER as to follows a phrase indicating a clear answer is not available, or that to give a clear answer is difficult or unexpected ↓ (further research with more co-text) ‘[negative] [clear] answer as to [wh-word] apply to only ANSWER useless as a generalisation 3.4 Coping with a lot of data: using phraseology Sinclair (1999) selecting 30 random lines, and noting the patterns in them, then selecting a different 30, noting the new patterns, then another 30 and so on until further selections of 30 lines no longer yield anything new. ‘hypothesis testing’ A small selection of lines is used as a basis for a set of hypotheses about patterns. Other searches are then employed to test those hypotheses and form new one. This is a way of investigating a very frequent word without being faced by thousands of lines at once. 3.4.1 Suggestion SUGGESTION + finite clause, SUGGESTION as to, SUGGESTION for, SUGGESTION of ↓ SUGGESTION of, SUGGESTION for, SUGGESTION to, (no SUGGESTION as to) ↓ SUGGESTION for, SUGGESTION to, SUGGESTION as to ↓ SUGGESTION for: occurs over 1,000 times in the Bank of English corpus … a significant part of the way SUGGESTION behaves SUGGESTION to: the to-infinitive clause is dependent on a word other than SUGGESTION ↓ the to-infinitive clause explains what the suggestion is the to-infinitive clause means something like ‘in order to’ ↓ SUGGESTION does have a pattern in which it is followed by a to-infinitive, but that pattern is not exemplified by all 200 lines of SUGGESTION to SUGGESTION as to: followed by a clause beginning with a wh-word 3.4.2 Point The search may be based on what comes before point what comes after point a word-class ↓ Each phrase illustrates a different meaning Point indicates the name of a place and a way of scoring in a game. It is used with this or that to refer back to something that has been said before. 3.5 Using a wider context: observing hidden meaning 3.5.1 I must admit A larger context than a concordance line is needed to find out about patterning when subtle meanings and usages are being observed. e.g.) par for the course In general terms: ‘this kind of thing is to be expected’ Channell’s investigation: ・It is used to comment on events which are negatively evaluated, not on events that are desirable. ・In spoken English, the phrase is often used by one speaker apparently to express solidarity with another speaker who is reporting a frustrating, annoying or inconvenient event. e.g.) I must admit (Establishing a pattern from the different instances) ・The speaker uses I must admit when saying something that is uncomplimentary, either about the hearer or about a third party ・What the speaker says or implies contradicts what a previous speaker has said. ・The speaker says something that is potentially embarrassing to him or herself, not to the hearer. ↓ The common theme is the need for a speaker to protect their own face or that of their hearer. (Brown and Levinson) ↓ Genreralisation: I must admit mitigates a threat to face. (Considering a counter-example) A previous speaker has spoken at some length about her dislike of hearing swear-words in public. I must admit I don’t like to hear bad language in the street. The speaker may dislike hearing bad language in the street, but may not object to it in other contexts. The speaker does not actually say this, but maintains his integrity by implying a measure of disparity between their opinions. ↓ The general theory is not necessarily falsified. 3.5.2 SIT through SIT through demonstrates what is sometimes called semantic prosody. SIT through follows have to (= connotation) an expression indicating the pressure has been exerted an expression indicating that someone does not want to do something The experience being undergone is unpleasant in some way ↓ sat through, sitting through ↓ SIT through is followed by an indication of a specific length of time by an indication that the length of time is judged to be uncomfortably long ↓ Use of SIT through implies boredom or discomfort. ↓ Considering a counter-example our home grown industry and having sat through this delightful, acid, piece ↓ ‘Hidden meaning of SIT through can be overridden. SIT through carries connotations of ‘boredom’ amassed through the typical contexts. The connotations hold unless there is very clear evidence to the contrary. Typicality is crucial here, because the connotation cannot be observed by examining one or two instances of the phrase, but depends on its most frequent contexts. 3.6 Using probes Probes: searches to find sets of words or expressions that cannot easily otherwise be called to mind e.g.) how men and women are typically evaluated: something/nothing + adjective + about/in + him/her ・Adjectives focusing on the construal of age and sexuality: boyish, childlike, masculine, womanly ( examples found in the male list only) ・We evaluate people in terms of their moral and psychological characteristics ・We evaluate people surprisingly often in terms of how much like other people they are, with how much confidence we are able to understand them e.g.) would like ・ways of expressing possible or hypothetical events other than with an if-clause or a when-clause: otherwise, in the event of 3.7 Issues in accessing and interpreting concordance lines The techniques needed to access and interpret concordance lines ・the variation using the word, the lemma or the phrase as a target ・the need to edit the lines to separate the target phrase form others ・the need to sort lines to make the patterning in them more visible ・the fact that it is often necessary to look at only part of each line in a set of concordance lines in order to identify patterning. ・the need sometimes to look at more co-text than a short concordance line ・the need to tackle a large amount of data by looking at successive group of a small number of lines, forming and testing hypotheses; ・the need to concentrate on evidence for the ‘central and typical’; ・the need to consider apparent counter-examples; support the hypothesis or not Concordance lines present information; they do not interpret it. Interpretation requires the insight and intuition of the observer. To some extent, this is a disadvantage, as it complicates statistical work on corpora. The enormous benefit, however, is that the human eye can perceive features of language that were hitherto unguessed-at. Corpus interpretation ・ distinguishing between categories such as types of clauses ・ making generalizations about the association between the way a word is used and its meaning ・ making statements about ‘the way the world is’ --- interesting and difficult e.g.) There are roughly twice as many instances of left-handed as right-handed in the Bank of English corpus. Why? ― ・more left-handed people in the world ・the left-handed have a higher status ・right-handedness :‘norm’ and left-handedness:‘deviant’ deviance is more often mentioned than normality Looking at the lines themselves suggests that the third one is the most likely interpretation, but it is important to recognize that this is an interpretation of evidence, not ‘fact’. *** New Terms *** p.39 node word p.42 typical, typicality p.43 central, centrality p.43 prototypical p.45 semi-grammatical words p.49 frames p.52 hypothesis testing p.60 semantic prosody p.62 probes References: http://www.soc.hyogo-u.ac.jp/tani/ch3.html