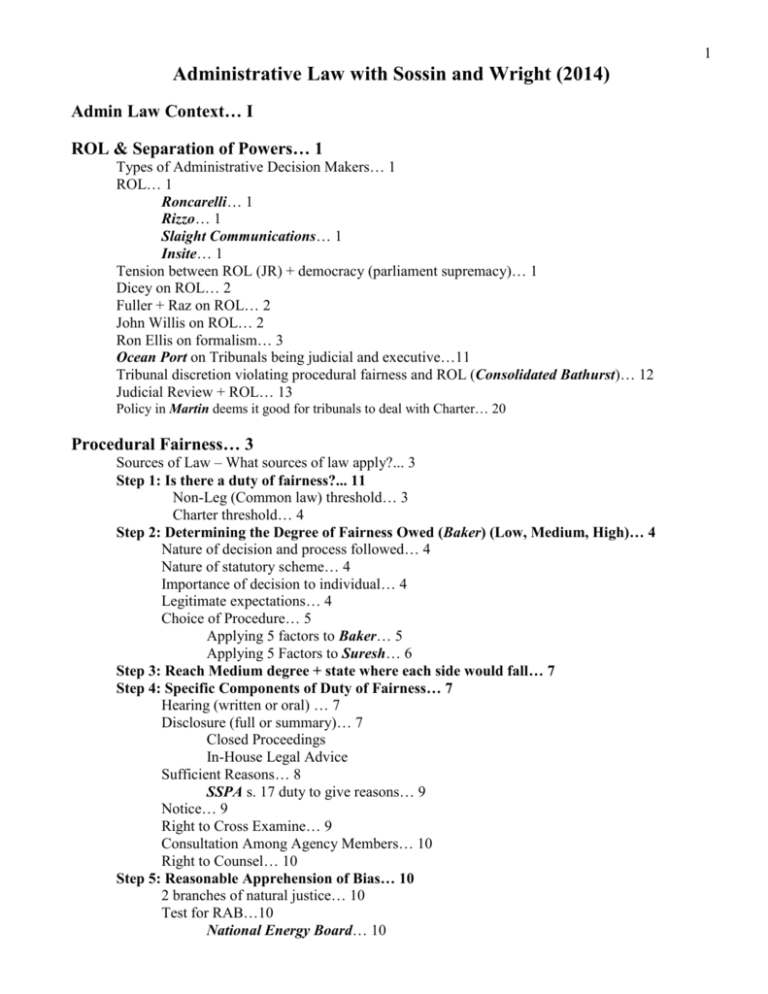

Administrative Law - (Sossin and Wright) - 2013-14 (1).

advertisement