Honors American Literature and Composition

advertisement

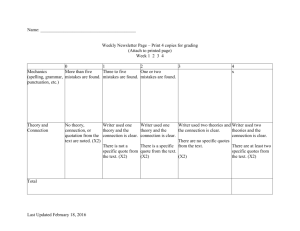

2015 Summer Reading—Honors American Literature and Composition Required Reading Overview The Creekside High School English Department believes that summer reading can be beneficial in honing students’ analytical skills, laying the foundation for a classroom community, fostering independent reading; and, most, supporting students’ appreciation for literature. Our hope is that providing students with high-interest texts and meaningful assignments will encourage your reading and promote both your oral and written analysis of the text. Thus, students taking Honors American Literature and Composition at Creekside High School are required to read the contemporary, American memoir Finding Fish by Antwone Fisher. One of the essential questions in American Literature and Composition is how do our economic, social, political, geographic, and personal contexts/situations shape who we are as Americans. Antwone Fisher’s memoir allows students to explore one possible answer to this question. As you read, consider how you might respond to the two- part assignment below. Assignment 1: Write a comparison contrast essay in which you compare the memoir Finding Fish to the movie Antwone Fisher (PG-13). Purpose: Please remember this important aspect of literary analysis: “It is important for you to keep literary analysis in perspective: analyzing a work is a means toward appreciation and evaluation, not an end in itself.” Sometimes students think they have fulfilled the requirements for an A paper by comparing two characters without any mention of the theme or the insight such a comparison or analysis lends. You MUST have a reason for writing what you write (other than it is a requirement for this class). [What insight, what truth is revealed by a careful analysis of your topic?] Source: Danny Lawrence, College Board AP instructor Use your prewriting notes on the similarities between the concepts. Find a sound bases for comparison. Remember that you can actually compare apples to oranges, but the point is that you really want to compare apples to apples. Your comparisons need to be cogent (convincing). Write a clear thesis statement. The thesis statement should identify the subjects and the purpose of your comparison. To help you formulate your thesis statement, ask yourself the following questions: What similarity do I want to show? Am I introducing a subject that may be unfamiliar to my readers, or am I attempting to refine my readers’ understanding of the similarities between the two subjects? Gather and organize information. Using your thesis statement as a guide, identify the most important points of comparison—the relevant features. Use your graphic organizer again to list the relevant features, and then compare each subject on each of those features. For example, in a comparison of rock music and blues music, relevant features might include rhythm, instrumentation, lyrics, audience, and performers. There are two basic patterns for organizing a comparison. With subject-by-subject organization, you fully discuss one subject, and then the other. With the featureby-feature pattern, you address each feature in turn and show how the subjects are similar. The chart below shows the two patterns of organization. Subject-by-Subject/Block Introduction Subject 1 Feature 1 Feature 2, Feature 3, etc. Subject 2 Feature 1 Feature 2 Feature 3, etc. Conclusion Feature-by-Feature/ Point by Point Introduction Feature 1 Subject 1 Subject 2 Feature 2 Subject 1 Subject 2 Feature 3, etc. Conclusion Here is an explanation of these two patterns of organization for comparison/contrast essays: Key: organization is evident. Thesis: Mom’s Hamburger Haven is a much better restaurant than McPhony’s because of its superior food, service, and atmosphere. Subject-by-Subject/Block A. Mom’s 1. Food 2. Service 3. Atmosphere B. McPhony’s 1. Food 2. Service 3. Atmosphere Feature-by-Feature/ Point by Point Point 1: Food A. Mom’s B. McPhony’s Point 2: Service A. Mom’s B. McPhony’s Point 3: Atmosphere A. Mom’s B. McPhony’s *** If you use the subject-by-subject/ block pattern, you should discuss the three points—food, service, atmosphere—in the same order for each subject. In addition, you must include in your discussion of subject “B” specific references to the points you made earlier about subject “A.” In other words, because your statements about Mom’s superior food may be several pages away by the time your comments on McPhony’s food appear, the readers may not remember precisely what you said. Gently, unobtrusively, remind them with a specific reference to the earlier discussion. For instance, you might begin your paragraph on McPhony’s service like this: “Unlike the friendly, attentive help at Mom’s, service at McPhony’s features grouchy persons who wait on you as if they consider your presence an intrusion on their privacy.” The discussion of atmosphere might begin, “McPhony’s atmosphere is as cold, sterile, and plastic as its décor, in contrast to the warm, homey feeling that pervades Mom’s.” Without such connecting phrases, what should be one unified essay will look more like two distinct mini-essays, forcing readers to do the job of comparing or contrasting for you. Source: Danny Lawrence, College Board AP instructor Write an introduction. The introduction to your composition should present the subjects being compared and state the purpose of your comparison. Be sure to include a brief introduction of the concept so that you can place it in its proper context. To draw your readers into your composition, you might begin by showing a striking contrast or an often overlooked similarity between your subjects. The introduction should narrow to the thesis, which will be the last sentence in your introductory paragraph. Draft. As you write, keep your thesis in mind. Be sure to discuss each relevant feature you have identified. Choose one pattern of organization and follow it throughout your composition. As you write the body, remember that transitions are effective signals to the reader to show whether you are discussing similarities or differences. Sophisticated transitions are parallel phrases, clauses, and synonyms that link sentences or paragraphs. The topic sentences should refer to the overall thesis idea and/or the idea discussed in the previous paragraph and should refer specifically to the new ideas to be discussed in the paragraph. The number of paragraphs will be at your discretion. I do expect good topic sentences and specific support/evidence from the individual works to develop those paragraphs. Write a conclusion. I will expect a good concluding paragraph for this essay also. End your composition on a strong note. You have put forth so much effort; do not merely “whimper off the page.” In addition to restating the main idea (not a summary of what you have written), draw a conclusion about the subjects you have compared. What is the purpose of having written the comparison? Ask yourself so what? after each sentence in your conclusion to help you polish your concluding paragraph. Document correctly. When you cite from the text in your essay, use quotation marks around directly quoted material. Follow the quotation with page number(s) in parenthesis. Final punctuation should follow the parenthesis. If the quote runs four or more lines block or center the quote. In this instance, the final punctuation mark precedes the final parenthesis. To cite a movie in an essay, see https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/747/02/ If you change the original text to fit your own prose, you should indicate the change in brackets [ ]. Do not consult secondary sources for written comparative essays on the two texts, doing so, may put you in jeopardy of unknowingly copying what you find. Tip: If you get stuck or have writer’s block, go to the website of a large university’s writing center where you will find guidelines like the ones provided here as well as sample essays. http://writingcenter.unc.edu/ Source: the bulleted notes above are adapted from Danny Lawrence, College Board AP instructor and various text books. Resources: If you need some more advice/inspiration to get started, check out the website: http://www.readwritethink.org/materials/compcontrast/ Basic Checklist Have you drafted, revised, and edited your essay at least twice? Have you headed your paper correctly, titled your paper accordingly, and followed MLA format? Have you chosen sound features to make your comparison worthwhile? Does your introduction provide brief expository information to place the concepts within their respective contexts? Is your thesis open? Does it present your thesis statement clearly and present the purpose of your comparison? Have you identified the relevant features to be compared and analyzed them thoroughly? Have you included specific details, quotes, and examples from the text(s) to support your comparison? Have you drawn a specific conclusion and ended your composition on a strong note? Have you used appropriate transitions to show similarities between the subjects of your comparison? Are your transitions sophisticated (synonyms, pronouns, phrases, and clauses) which help to link/connect ideas? Have you used subject-by-subject or feature-by-feature organization? Is the essay written formally in the third person? Have you eliminated contractions, slang, and conversational (colloquial) language? Have you spelled the characters’ names correctly, italicized the titles of the works, and eliminated grammatical errors including punctuation, sentence structure, mechanical, pronoun-antecedent agreement, misplaced and dangling modifiers, parallelism, subject/verb agreement, and spelling errors? Have you written in the literary present? Have you written no more than 2 fully developed pages? Have you read a sample essay comparison contrast essay—not on your topic? Are you ready to submit your essay? Source: adapted from various text books. Comparison Contrast Rubric ELACC11-12W2 : Write informative/explanatory texts to examine and convey complex ideas, concepts, and information clearly and accurately through the effective selection, organization, and analysis of content. (CCGPS) ELACC11-12RL7 : Analyze multiple interpretations of a story, drama, or poem (e.g., recorded or live production of a play or recorded novel or poetry), evaluating how each version interprets the source text. (CCGPS) Domains Introduction ELAW2: a. Introduce a topic; organize complex ideas, concepts, and information so that each new element builds on that which precedes it to create a unified whole. Thesis Formulates a coherent thesis/claim or controlling idea. Conclusion ELAW2: f. Provide a concluding statement or section that follows from and supports the information or Exceeds Standard 14-15 The writer produces an engaging hook and provides expository information Meets Standard Approaches Standard 11-10 The writer gives a perfunctory overview and/or leaves out a couple of important aspects of the exposition. The writer’s introduction is one of the ineffective introductions: “Place Holder,” “Book Report,“ Restated Question,” “Webster’s Dictionary,” or “The Dawn of Man Introduction.” Emergent/Beginning 14-15 The writer constructs a clearly stated thesis which reveals a sound bases for comparison as well as a meaningful purpose for analysis. 14-15 The writer produces a strong (welldeveloped) concluding paragraph which advances an idea and discusses the 13-12 The writer creates a thesis which reveals a sound bases for comparison and an evaluative purpose. 11-10 The paper forms a thesis that may be obvious and/or the purpose for comparison is not articulated. 9-0 The writer does not articulate a thesis. The writer’s paper does not have an evaluative purpose, or the writer’s thesis statement is convoluted. 13-12 The writer provides a sound conclusion which takes an idea one step further or advances an 11-10 The writer gives one of the four types of ineffective/weak conclusions: “That’s My Story and I’m Sticking to It” “The Sherlock Holmes,” 9-0 The writer has no conclusion or offers a mere, cursory restatement of the introductory paragraph and thesis. 13-12 The writer provides the basic expository requirements of the essay. 9-0 The writer offers little or no expository information, or the introductory paragraph is not evident. explanation presented (e.g., articulating implications or the significance of the topic). Purpose and Supporting Details ELAW2: b. Develop the topic thoroughly by selecting the most significant and relevant facts, extended definitions, concrete details, quotations, or other information and examples appropriate to the audience’s knowledge of the topic Organization and Structure ELAW2: c. Use appropriate and varied transitions and syntax to link the major sections of the text, create cohesion, and clarify the relationships among complex ideas and concepts. implications of the reasoned analysis. 14-15 The writer compares items clearly. The writer points to specific examples to illustrate the comparison. idea. 13-12 The writer includes only the information relevant to the comparison. “America the Beautiful,” “I am Woman [Man],” “We Shall Overcome,” or Grab Bag Conclusions.” 11-10 The writer compares items clearly, but the supporting information is incomplete. The writer may include information that is not relevant to the comparison. 9-0 The writer does not fully compare the two subjects. The writer has no supporting information or the support is incomplete. 11-10 The writer breaks the information into block/ subjectbysubject similarities or feature-by feature/ point-bypoint structure, but some details are not in a logical or expected order which distracts the reader. 9-0 The writer digresses so there is little sense that the writing is organized and logical. 13-12 14-15 The writer breaks the information into block,/subjectby-subject similarities or featureby-feature/pointby point structure. The writer follows a consistent order when discussing the comparison. The writer breaks the information into block/subject-bysubject or feature-by feature/ point-bypoint structure but does not follow a consistent order when discussing the comparison. Transitions Maintains coherence by relating all topic sentences to the thesis/claim or controlling idea, as applicable. Conventions (Grammar, Usage, and Mechanics) ELA12C1: ELACC11-12L1 : Demonstrate command of the conventions of standard English grammar and usage when writing or speaking. (CCGPS) 14-15 The writer moves smoothly from one idea to the next. The writer uses comparison and contrast transition words to show relationships between ideas. The writer uses a variety of sentence structures and transitions. 13-12 The writer employs transitions which move from one idea to the next, but there is little variety. The writer uses comparison and contrast transition words to show relationships between ideas. 11-10 The writer uses some transitions which work well, but the connections between other ideas are fuzzy. 9-0 The writer’s transitions between ideas are unclear or nonexistent. 14-15 The writer has 1-2 errors in grammar, spelling, or usage that distracts the reader from the content. 13-12 The writer has 3-4 errors in grammar, spelling, or usage that distracts the reader from the content. 11-10 The writer has 5-6 errors in grammar, spelling, or usage that distracts the reader from the content. 9-0 The writer has more than six errors in grammar, spelling, or usage that distracts the reader from the content. 10-9 8-7 6-5 4-0 Adapted from: NCTE read write think copyright 2004. Assignment 2: ELACC11-12RI7 : Integrate and evaluate multiple sources of information presented in different media or formats (e.g., visually, quantitatively) as well as in words in order to address a question or solve a problem. (CCGPS) Life Box “The objects people carry around can tell a lot about them at that precise moment in time. They could describe what they do for a living or where they are going. You could call these things ‘character life boxes,’ because they reveal something about a person’s life.” Source: http://artsedge.kennedy-center.org/educators/lessons/grade-68/Character_Life_Box#Instruction Purpose: In literature, for a character to become interesting, the writer must create specific and believable details that will make us care about this individual. Some reasons that we may care about characters are: We have something in common with them. Something about them is familiar to us, they remind of us someone we know, like, or dislike. [In essence], we understand their goals, dreams, successes or failures. Source: http://artsedge.kennedy-center.org/educators/lessons/grade-68/Character_Life_Box#Instruction “The ‘life box’ offers [you] a hands-on opportunity to understand characterization” in nonfiction “literature and to connect historical and contemporary culture.” Through research and study of the memoir Antwone Fisher, you will collect props, which will serve as symbols and clues to create a “life box.” Source: adapted from http://artsedge.kennedy-center.org/educators/lessons/grade-68/Character_Life_Box#Instruction Instructions: 1. Using the memoir, research information about the historical context in which Fisher grew up. The National History Museum is a sound source for images. See http://americanhistory.si.edu/ . 2. Create a “character life box” for Antwone Fisher. 3. Choose five items to place inside the box. These items should be symbolic of Fisher’s “goals, dreams, successes, and/or failures.” 4. Provide five quotes (textual evidence) from the memoir which supports your symbol. 5. Present your “Life Box” to the class. Source: adapted from http://artsedge.kennedy-center.org/educators/lessons/grade-6-8/Character_Life_Box#Instruction Source: adapted from http://blogs.pennmanor.net/lorihuel/2009/12/01/character-box-requirements-andrubric/ Rubric: Character Box Project Requirement/Criteria Points Possible 75/75 Points Earned The student stores the items in a literal or virtually decorated box or container. ELACC11-12W7 : Conduct short as well as more sustained research projects to answer a question (including a self-generated question) or solve a problem; narrow or broaden the inquiry when appropriate; synthesize multiple sources on the subject, demonstrating understanding of the subject under investigation. (CCGPS) The student decorates a box depicting images from the geographic, social, political, economic, and personal contexts in which Fisher grew up. Descriptors: aesthetically pleasing, neat, relevant to the character and the period, prepared before class presentation 5x5 =25 Points 4x5=20 Points 3x5=15 Points 2x5=10 Points 1x5=5 Points ELACC11-12RL7 : Analyze multiple interpretations of a story, drama, or poem (e.g., recorded or live production of a play or recorded novel or poetry), evaluating how each version interprets the source text. The student has written specific textual support which explains why each of the five symbolic or literal objects was chosen and what it reveals about the character. Think analysis. 5 x5= 25 4 x 5= 20 3 x 5=15 2 x 5= 10 1 x 5= 5 ELACC11-12SL1 : Initiate and participate effectively in a range of collaborative discussions (one-on-one, in groups, and teacher-led) with diverse partners on grades 11–12 topics, texts, and issues, building on others’ ideas and expressing their own clearly and persuasively. (CCGPS) The student presents the “life box” to the class. Student uses a clear voice and correct, precise pronunciation of terms. The student consistently listens to and asks questions about his or her classmates’ presentations. 5 x 5= 25 4 x 5= 20 3 x 5= 15 2 x 5= 10 1 x 5= 5 Source: Adapted from http://blogs.pennmanor.net/lorihuel/2009/12/01/character-box-requirements-andrubric/