Date: 15-08-2014 Author: Guus Visman Student number: 349144

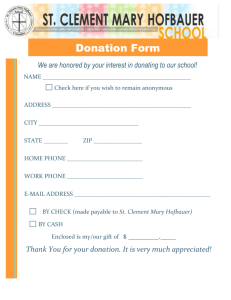

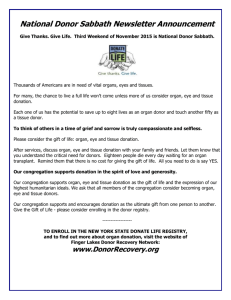

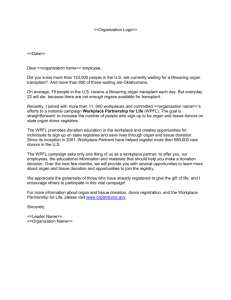

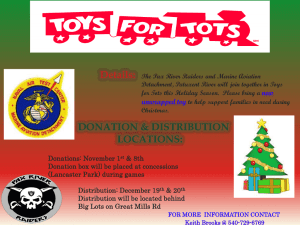

advertisement