Sparta - Haiku

advertisement

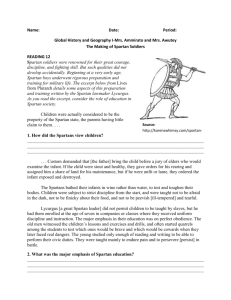

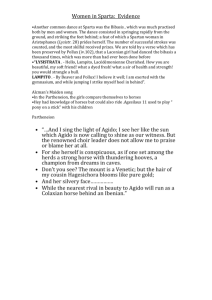

“Using sources you have studied, assess the social and political features of Spartan Society that made it unique throughout Greece” Spartan society is portrayed by modern and ancient sources as austere and militaristic and to be constructed on the principles of survival of the fittest, class-based hegemony and, to a degree, socialism. Both ancient sources, “clearly…the most powerful and most famous state in Greece (Xenophon, p. 194) and modern, “the original utopia” (Cartledge, 2002, p. 22) have a great appreciation for Spartan society. Significantly, Sparta was incredibly different from all the other Greek states regardless of their relative geographical proximity. It can be seen how considerably distinct Spartan society was from the rest of Greece by looking at social features such as the presence of a strong class system and the unique role of women, and the political framework of Spartan society. By looking at these elements of Sparta and comparing it to the other Greek city states, the sheer austerity and dissimilarities of the society can be easily identified. Social components of Spartan society made it quite distinct from the rest of the Greek city states. Most significant of these was the class system of Sparta, upon which the whole society was dependent on to function. Sparta had two primary social classes: the homoioi or Spartiate who were the full members of the state and the servant Helot class. Additionally the Spartan state had the Perioeci, who supplemented the lack of craftsmen and economic functionaries among the Spartiate class. What was unique about the Spartan social structure in comparison to the rest of Greece was that typically Greek states would have a citizen class that was free to go down their avenue of life, and mostly “important foreigners of barbarians” (Cartledge, 2002, p. 67) would work for them. Instead, in Sparta a Sparitate was expected to live a rigorous militaristic life that only allowed the fit to survive. A Spartiate would be examined for his strength from birth, where if “the baby was puny…they dispatched it to what was called ‘the place of rejection’…considering it better both for itself and the state” (Plutarch, p. 20). From the age of seven to about eighteen they would be brought up by the Agoge, a thorough militaristic training program for the young Spartiates. For the rest of their life they would be involved in constant drilling and training, as Plutarch puts it, “Spartiates training extended into adulthood, for no one was permitted to live as he pleased” (Plutarch, p. 29). On the other side of the coin were the Helots, “serf-like peasants” who “provided the economic basis of their unique lifestyle” (Cartledge, 2002, p. 27). What was truly different of the Helots to the other Greek slave classes was that they “shared their masters’ culture and language” (Cartledge, 2002, p. 67) and essentially, were a “Greek ethnic group enslaved en masse” (Cartledge, 2002, p. 67). The Spartiate and Helot classes highlight the significant uniqueness of the Spartan state to the rest of Greece, as while the other Greek states allowed a more liberal lifestyle for its populace and used foreigners for slaves, the Spartiates were held to a military law-code for their life and used the conquered Messenians to supply their servant class so that they could be entirely focused on their military routine. As well as the strong class system of Sparta, the unique role of women in Spartan society is characteristic to its uniqueness to the other Greek states. As Xenophon puts it, “elsewhere girls who are prospective mothers and considered to be well brought up are fed the plainest practicable diet… [they] require girls to be sedentary” (Xenophon, p. 194). Spartan women were brought up very differently to other Greek women. Rather than being “sedentary”, Spartan women were “required…to take physical exercise just as much as males” (Xenophon, p. 194) and to contest the men in strength and speed. The overall aim of this was to prepare women for “the challenge of childbirth” (Plutarch, p. 17), as in Spartan society “the production of children was the most important duty of free women” (Xenophon, p. 194). Additionally, women were bred to be “fit partners for the men and fit mothers of future Spartan warriors” (Cartledge, 2002, p. 63). By this token, Spartan women were not given a place in the army, but were “formally educated and socialised” (Cartledge, 2002, p. 63). Along with their unique role of procreation in Spartan society, women also played a role in the maintenance of managing the household and the kleros. As the kleros and the Helots attached to it was the means of production in Spartan society, Spartan women were able to distinguish themselves from other Greek women by their accessibility to wealth. Pomeroy claims that by Aristotle’s time women owned two-fifths of the land and that Spartan women were the wealthiest women in mainland Greece (Pomeroy, p. 82). This demonstrates how women in Sparta had two unique roles, compared to other Greek women: they were brought up for the purposes of childbirth, and they had a profound access to the collection of wealth. Further, it demonstrates how unique Spartan society was in ancient Greece. The political framework also was a unique construct to Spartan society. Rather than being a conventional form of monarchy or a new democracy like their Greek neighbours, the Spartan political system took elements from monarchy, oligarchy and democracy. The monarchical element was represented by the two kings of the Agiad and Europontid royal families. Kings had the role of chief priest, and “by virtue of his divine descent, should perform all the public sacrifices on the city’s behalf” (Xenophon, p. 211). Kings also presided over the ekklesia with the gerousia of thirty elders, whom represented the oligarchic element of the Spartan political framework. Additionally, five ephors; executive members of the Spartan political body, further represented this oligarchic element. Processes in the ekklesia of putting notions to the people and allowing a vote of ‘acclaim’ for elders by the people reflected the democratic aspect of Sparta’s political system. In addition to the system itself, what was particularly Spartan in this system was that it prevented the state from falling into a state of tyranny from the monarchs or from the people (Plutarch, p. 8). Instead, it struck a fine balance between the two. Plutarch comments on this system as being greater to the other Greek political systems, “initially their circumstances and those of the Spartans had been equal…however they did not prosper very long, but through their insolence of their kings…and the non-cooperation of their masses…they threw their institutions into complete turmoil” (Plutarch, p. 10). Plutarch’s quote demonstrates not only how unique the political framework was to the other Greek states, but how effective the Spartan system was compared to theirs. Moreover, the Spartan political system was incredibly significant in terms of its uniqueness to Sparta in Greece. While “the Spartans were considered in antiquity to be intriguing, extreme and even alien” (Cartledge, 2002, p. 22), their austerity and uniqueness brought them a greater level of social and political success. This can be seen in relation to the strong class system, the role of women, and the political framework of Spartan society. Spartan soldiers were revered throughout Greece, Spartan women were considered “the most beautiful in all Greece” (Cartledge, 2002, p. 50) and Spartan governments remained more stable than their Greek counterparts, as demonstrated by Plutarch. Therefore, the social and political qualities of Spartan society were incredibly significant to the uniqueness of the Spartan state, and to its success as a state.