Seren essay annotate.. - UCL Department of Geography

advertisement

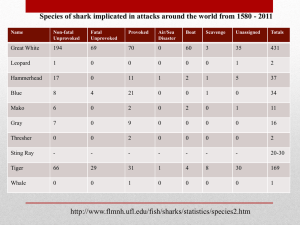

Jan Axmacher Changing Landscapes Candidate Number: YNVH4 Investigate the Implications of the Use of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) and Chinese Cooking for Nature Conservation with Specific Focus on Aquatic Organisms. Wildlife and humans coexist in an intricate relationship; people value wildlife as a source of income, food and medicine as well as representing cultural symbols (Alves and Rosa, 2007). From an ethnomedicinal perspective, wildlife represents an immeasurable source of information and raw materials, which support health systems of different human cultures that depend on nature as a source of medicines to treat and cure illnesses (Zhen, 2009). Naturally occurring substances such as plant, animal and mineral sources have provided a continuing supply of medicines since the earliest times (Alves and Rosa, 2012). The use of these traditional medicines have provided a crucial support and health system to millions of people around the globe for centuries and this has continued and influenced the present day (Alves et al., 2012). Traditional medical systems throughout the world have been relied on to support, promote, retain and regain human health for millennia. It has been estimated that between 70 and 95% of citizens in a majority of developing countries, especially those in Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East use traditional medicine for the management of health and as primary health care to address their health care needs and concerns (Xue et al., 2010). The healing of human ailments by using therapeutics based on medicines obtained from animals or ultimately derived from them is known as zootherapy (Lev, 2003). Undoubtedly the basis of many of these traditional medicines contains parts of plants and animals, however the pharmacological using animals in medicines have been little explored. Available studies have nevertheless shown that animal natural resources are highly promising in the search for new drugs of medical pharmaceutical interest (Souto et al., 2012). As the demand for these resources are so high, inevitable exploitation has been seen. There is a need for careful strategy due to the exploitation of aquatic organisms through bioprospecting as there is a growing demand for their medicinal purposes that can lead to sever overharvesting of target species (Seedhouse, 2011). In view of this reality, economic development associated with animal bioprospecting should be preceded by a broad discussion of the conservation of biodiversity and the sustainable management of natural resources (Harvey, 2012). Aquatic mammals from various sizes have been sourced for their use in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) since ancient times (Guo et al., 1997). However, there is growing concern towards their use, as they are also among the most threatened animal taxa worldwide (Still, 2003). At least 24 species of aquatic mammals are used in TCM, although all these species are listed in the IUCN Red List and include critically endangered species (Yi-Ming et al., 2000). The medical value of aquatic animal species has also not been included in the calculations of the economic value of biodiversity by the World Conservation Union (IUCN) (Alves, and Rosa, 2005). The medicinal use probably does not pose major threat to most aquatic mammals, nevertheless their exploitation for Jan Axmacher Changing Landscapes Candidate Number: YNVH4 medicinal purposes is troubling, as it constitutes an additional and persistent impact for a group of animals that have suffered major direct impacts, especially from ocean habitat degradation and over fishing, as well as impacts related to global warming (Zhang et al., 2008). Oceans are the Earth’s most valuable natural recourses, which provide majority of the food in form of fish and shellfish; about 200 billion pounds are caught each year (Burge et al., 2013). Oceans are the richest resources for numerous biomedically important chemicals as well as protein molecules, which range from general medication proposes to the specific therapeutic applications (Jha and Zi-rong, 2004). Developments of medicines from the sea are quickly becoming seen as the best at present day because there is a conventional belief that “life originated from the sea” (Pitchford, 2002). Asians supplement their regular diet with seafood, which provides them more proteinaceous and medically valuable ingredients. They view a healthy and nutritious life as being able to source the right food, thus the search for medicinal foods and remedies are still continuous from marine resources (Gould and Villarreal, 2006). Many of the aquatic organisms found in TCM are part of trading processes throughout China (Chan et al., 2003). Since demand is high it’s a lucrative market with huge earning potential for buyers and sellers. One of the most alarming trades is from shells of hard shelled and soft shell turtles (Alves et al., 2012). Turtles and tortoises have long been utilized in East and Southeast Asia for food, medicines and pets; China is the largest consumer country in the world (Fund, 2002). Due to burgeoning demand in the market following rapid economic growth, over one-half of freshwater turtle and tortoise species from Southeast and East Asia have been severely threatened by overexploitation for food and traditional medicines (Parham et al., 2001). The turtle shells (plastrons from hard-shelled species and carapaces from soft-shell species) have long been used as an ingredient for TCM in many societies with Chinese cultural origins and affinities in East and Southeast Asia and other overseas Chinese communities around the World (Gong et al., 2009). However, the trade in turtle shells has never been systematically monitored and very few long-term data reports are available (Schlaepfer et al., 2005). Although a study carried out by Chen et al in 2009 showed that based on custom trade statistics from 1999 to 2008, a total of 1989 metric tons of hard shells have been imported into Taiwan for consumption in the TCM market, with an average of 198.9 metric tons per year (Chen et al., 2009). Soft-shells were also imported and a figure of 290 metric tons was recorded, averaging 29.0 metric tons per year (Chen et al., 2009). This volume indicates that millions of turtles and tortoises have been killed annually for the TCM market in Taiwan alone. The custom trade records however were not species specific but Chen et al did discover through surveying methods that in 1996-2002 a total of 39 species of the turtles and tortoises in this trade mainly originated from China. Only 3 nonAsian species were found whilst surveying. The TCM market is a closed community and the domestic trade is very poorly documented due to the limited oversight by the responsible agencies, this means that data access relies purely on international trade statistics of custom reporting systems (Broad et al., 2001). The larger number and numerous species of origin in turtle-shell trade for the Jan Axmacher Changing Landscapes Candidate Number: YNVH4 TCM market indicate blatant disregard by traders for law and authority countries (Cheung and Dudgeon, 2006). The trade of turtle shells appears to be highly unsustainable and may have great impact on the chelonian fauna in Asia due to the absence of turtles and tortoises in the food chain (Shiping et al., 2006). Clear policies and close international cooperation for the regulation of turtle shell trade are urgently needed. A similar trade can also be seen in manta and mobula rays across the TCM market, the appetite for these animals have put the population at sever risk (Alava et al., 2002). Labelled as a traditional medicine, there is actually no historical reference to this remedy in Chinese texts, so the term “traditional” cannot directly be applied accurately (Fernando and Stevens, 2011). However, the product is still being marketed as such but is extremely undocumented and many reports are based on speculation. They are hunted for their gill rakers, these are filaments that filter out plankton, krill and other food (Jaine et al., 2012). Demand in China for dried gill rakers as purported medicine for chicken pox and other aliments is down to a marketing pitch (Nijman and Nekaris, 2012). They are advertised through the belief that as manta rays are capable of filtering particles out of the water, if you consume the rakers yourself, it will filter impurities from your body (Hilton, 2009). It’s thought that this has drawn attention to the growing market, as there are increasing problems with bird flu, SARS and asthma from pollution (Still, 2003). This market pitch has tapped into people’s insecurities and the consumption of gill rakers are inevitably raising when twenty years ago they were an unheard of remedy (Fernando and Stevens, 2011). The increasing popularity of this trade means that a large manta can fetch several hundred dollars, versus $20 to $40 for its meat alone (Shyr, 2012). Last year it was stated that around 100,000 of the rays landed in global fish markets, this estimate included around a dozen mobuild species (Shyr, 2012). In 2004, manta rays were identified by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species as a group associated with significant unregulated, unsustainable fishing and sever population depletion (Stevens, 2012). In 2005, the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species classified the manta ray as “near threatened” (Dewar et al., 2008). If current fishing practices continue, certain populations are vulnerable too extinction in the future (Hilton, 2009). However, global extinction is far from sight but it is possible that populations will go, or have gone, regionally extinct. Some species of manta have been documented to be more vulnerable than others and there is a need of urgent research to understand the comprehensive management efforts that need to be put in place (Marshall, 2008). There is much still to be discovered on behalf of manta rays biology and physiology. A fear has set in across scientists who are making new discoveries into the life of a manta ray. Their slow maturity rates and infrequent pregnancies mean that populations cannot replenish themselves as fast as man is catching and killing them (Stevens, 2012). The shark fin trade is arguably the most important determinant of the fate of shark populations around the world (Clarke et al., 2006). Shark fins have been a traditional element of Chinese haute cuisine for centuries. They were first established as an ingredient in formal Chinese banquets prepared for the Jan Axmacher Changing Landscapes Candidate Number: YNVH4 emperor of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 AD) (Fabinyi et al., 2012). Although, during the Mao Zedong and early Deng Xiaoping eras, consumption was either discourages by policies of cultural reform or priced beyond the reach of all but the wealthiest consumers (Lack and Sant, 2006). However the consumption of shark fin has remained a status symbol by means of the same factors of exclusiveness and exoticism that fuel the demand for other rare wild animals in Chinese society. They are freely available to purchase in shops and restaurants and are advertised as prize dining features to make a restaurant exclusive and desirable. Fig 1. Below is a photo demonstrating the advertisement of shark fins ready for consumption. In addition to this, connections between shark fins and beliefs about health and vitality play a role in market demand (Worm et al., 2013). Products from animals known to be strong or fierce, such as sharks, were believed to impart strength to those who ate them and this are considered suitable for the imperial family (Fong and Anderson, 2000). There is no data complied on shark fin sales and volumes in Hong Kong or Mainland China, import data from national custom authorities are only available for indications of demand (Milner-Gulland and Bojorndal, 2008). As the demand is further explored attention needs to be drawn to regulatory and policy actions designed to discourage the practice of shark finning. Finning has arisen mostly from fisheries targeting high-value species such as tuna or billfishes (Clarke et al., 2006). The vessels that operate within Jan Axmacher Changing Landscapes Candidate Number: YNVH4 these fisheries often make lengthy trips with limited hold capacity and therefore do not wish to keep shark carcasses, but appreciate the high value of fins. Some vessels may also target sharks especially just for their fins however recent campaigns have urged coastal longline fleets that land large numbers of whole sharks to use both fins and meat, if only to make the processes more ethically bearable (Clarke et al., 2004). The current extent of finning is unknown and studies into the matter are not entirely welcomed. It is thus necessary to simultaneously work to rectify data deficiency while supporting precautionary measures as a hedge against scientific uncertainties. The most serious, and yet perhaps most easily remedied, data deficiency is that associated with frozen fin imports to China (TRAFFIC, East Asia, 2004). A decision by the Government of China to reverse the coding guidance of 2000 and ideally to separate dried and frozen and processed and unprocessed shark fin imports and exports as Hong Kong does, would greatly benefit all research into the shark fin trade (Norman and Catlin, 2007). In order to close unavoidable loopholes in the regulation of shark fins via fin-to-carcass weight ratios, finning regulations should be amended to require that sharks be landed with fins attached, as was specified in the State of Hawaii legislation in 2000 (Morita, 2000). To improve the conservation of aquatic animals that are associated with TCM there is need for action to be taken on the supply side of the economic equation. However consumer awareness and precautionary demand reduction campaigns could be extremely effective. The target audience for such campaigns would obviously be consumers and potential consumers in Mainland China, as no other group can so strongly affect the fate of sharks, manta rays and turtle populations (Still, 2003). These however are to only name but a few of the aquatic species that are being endangered by popular use of TCM. However, the use of animals for medicinal purpose is part of a body of traditional knowledge, which is increasingly becoming more relevant to discussion on conservation biology, public health policies, sustainable management of natural resources, biological prospection and patents (Costa-Neto, 2005). Coexistence is not out of the question if proper management and regularity is carried out in the trade of TCM. Nevertheless, the political web surrounding this broad statement is incredibly vast. Strong political will from the Chinese government is crucially needed along with proper environmental education to take a step towards new conservation methods in order to appreciate and protect these critically endangered species. Word Count – 1994 Jan Axmacher Changing Landscapes Candidate Number: YNVH4 References Alava, M. N. R., Yaptinchay, A. A., Dolumbal, E. R. Z., & Trono, R. B. (2002). Fishery and trade of whale sharks and manta rays in the Bohol Sea, Philippines. In Elasmobranch Biodiversity, Conservation and Management: Proceedings of the International Seminar and Workshop, Sabah, Malaysia, July 1997 (pp. 132-148). by: IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK.. Alves, R. R., & Rosa, I. L. (2005). Why study the use of animal products in traditional medicines?. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 1(1), 5. Alves, R. R., & Rosa, I. M. (2007). Biodiversity, traditional medicine and public health: where do they meet?. Journal of ethnobiology and ethnomedicine, 3(1), 14. Alves, R. R. N., Rosa, I. L., Albuquerque, U. P., & Cunningham, A. B. (2012). Medicine from the Wild: An Overview of the Use and Trade of Animal Products in Traditional Medicines. Animals in Traditional Folk Medicine, 25-42. Alves, R. R. N., Medeiros, M. F. T., Albuquerque, U. P., & Rosa, I. L. (2012). From Past to Present: Medicinal Animals in a Historical Perspective. Animals in Traditional Folk Medicine, 11-23. Broad, S., Mulliken, T., & Roe, D. (2001). The nature and extent of legal and illegal trade in wildlife (pp. 3-22). S. Oldfield (Ed.). London. Burge, C. A., Kim, C. J., Lyles, J. M., & Harvell, C. D. (2013). Special Issue Oceans and Humans Health: The Ecology of Marine Opportunists.Microbial ecology, 1-11. Chan, M. F., Mok, E., Wong, Y. S., Tong, T. F., Day, M. C., Tang, C. K. Y., & Wong, D. H. C. (2003). Attitudes of Hong Kong Chinese to traditional Chinese medicine and Western medicine: survey and cluster analysis.Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 11(2), 103-109. Chen, T. H., Chang, H. C., & Lue, K. Y. (2009). Unregulated trade in turtle shells for Chinese Traditional Medicine in East and Southeast Asia: the case of Taiwan. Chelonian Conservation and Biology, 8(1), 11-18. Cheung, S. M., & Dudgeon, D. (2006). Quantifying the Asian turtle crisis: market surveys in southern China, 2000–2003. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems, 16(7), 751-770. Clarke, S., McAllister, M. K., & Michielsens, C. G. (2004). Estimates of shark species composition and numbers associated with the shark fin trade based on Hong Kong auction data. Journal of Northwest Atlantic Fishery Science, 35, 453465. Jan Axmacher Changing Landscapes Candidate Number: YNVH4 Clarke, S. C., McAllister, M. K., Milner‐Gulland, E. J., Kirkwood, G. P., Michielsens, C. G., Agnew, D. J., ... & Shivji, M. S. (2006). Global estimates of shark catches using trade records from commercial markets.Ecology Letters, 9(10), 1115-1126. Costa-Neto, E. M. (2005). Animal-based medicines: biological prospection and the sustainable use of zootherapeutic resources. Anais da Academia Brasileira de ciências, 77(1), 33-43. Dewar, H., Mous, P., Domeier, M., Muljadi, A., Pet, J., & Whitty, J. (2008). Movements and site fidelity of the giant manta ray, Manta birostris, in the Komodo Marine Park, Indonesia. Marine Biology, 155(2), 121-133. Fabinyi, M., Pido, M., Harani, B., Caceres, J., Uyami‐Bitara, A., De las Alas, A., ... & Ponce de Leon, E. M. (2012). Luxury seafood consumption in China and the intensification of coastal livelihoods in Southeast Asia: The live reef fish for food trade in Balabac, Philippines. Asia Pacific Viewpoint. Fernando, D., & Stevens, G. (2011). A study of Sri Lanka’s manta and mobula ray fishery. The Manta Trust. Fong, Q. S. W., & Anderson, J. L. (2000). Assessment of the Hong Kong shark fin trade. Infofish International, (1), 28-32. Fund, T. C. (2002). A global action plan for conservation of tortoises and freshwater turtles. Strategy and funding prospectus, 2007, 30. Gong, S. P., Chow, A. T., Fong, J. J., & Shi, H. T. (2009). The chelonian trade in the largest pet market in China: scale, scope and impact on turtle conservation. Oryx, 43(02), 213-216. Gould, B. W., & Villarreal, H. J. (2006). An assessment of the current structure of food demand in urban China. Agricultural Economics, 34(1), 1-16. Guo, Y., Zou, X., Chen, Y., Wang, D., & Wang, S. (1997). Sustainability of wildlife use in traditional Chinese medicine. Conserving China’s Biodiversity, 190-220. Harvey, B. (2012). Blue genes: sharing and conserving the world's aquatic biodiversity. Routledge. Hilton, P. (2009). Manta Rays and Chinese Traditional Medicine. sourced via http://www.paulhiltonphotography.com/index.php/field-notes/9 on the 12th of March, 2013. Jaine, F. R., Couturier, L. I., Weeks, S. J., Townsend, K. A., Bennett, M. B., Fiora, K., & Richardson, A. J. (2012). When Giants Turn Up: Sighting Trends, Environmental Influences and Habitat Use of the Manta Ray Manta alfredi at a Coral Reef. PloS one, 7(10), e46170. Jan Axmacher Changing Landscapes Candidate Number: YNVH4 Jha, R. K., & Zi-rong, X. (2004). Biomedical compounds from marine organisms. Marine Drugs, 2(3), 123-146 Lack, M., & Sant, G. (2006). World shark catch, production and trade 1990-2003. Department of the Environment and Heritage. Lev, E. (2003). Traditional healing with animals (zootherapy): medieval to present-day Levantine practice. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 85(1), 107-118. Marshall, A. D. (2008). Biology and population ecology of Manta birostris in southern Mozambique. Milner-Gulland, E. J., & Bjorndal, T. (2008). Social, economic and regulatory drivers of the shark fin trade. Centre for the Economics and Management of Aquatic Resources, University of Portsmouth. Morita, E. L. (2000). 2000 Legislative Session: Important Legislation for Practicing Attorneys, The. U. Haw. L. Rev., 23, 389. Nijman, V., Nekaris, K. A. I., & Bickford, D. P. (2012). Asian medicine: Small species at risk. Nature, 481(7381), 265-265. Norman, B., & Catlin, J. (2007). Economic importance of conserving whale sharks. Report for the international fund for animal welfare (IFAW), Australia. Parham, J. F., Simison, W. B., Kozak, K. H., Feldman, C. R., & Shi, H. (2001). New Chinese turtles: endangered or invalid? A reassessment of two species using mitochondrial DNA, allozyme electrophoresis and known‐locality specimens. Animal Conservation, 4(4), 357-367. Pitchford, P. (2002). Healing with Whole Foods: Asian traditions and modern nutrition. North Atlantic Books Schlaepfer, M. A., Hoover, C., & Dodd Jr, C. K. (2005). Challenges in evaluating the impact of the trade in amphibians and reptiles on wild populations. BioScience, 55(3), 256-264. Seedhouse, E. (2011). Ocean Medicine. Ocean Outpost, 141-150. Shiping, G., Jichao, W., Haitao, S., Riheng, S., & Rumei, X. (2006). Illegal trade and conservation requirements of freshwater turtles in Nanmao, Hainan Province, China. Oryx, 40(03), 331-336. Shyer, L. (2012). Manta and mobula ray numbers are falling as they’re hunted for Asian remedies. National Geographic. Volume. 222. Issues 2, p16. Souto, W. M. S., Pinto, L. C., Mendonça, L. E. T., Mourão, J. S., Vieira, W. L. S., Montenegro, P. F. G. P., & Alves, R. R. N. (2012). Medicinal Animals in Jan Axmacher Changing Landscapes Candidate Number: YNVH4 Ethnoveterinary Practices: A World Overview. Animals in Traditional Folk Medicine, 43-66. Stevens, G. (2012). Manta Rays and the Chinese Medicine Trade: An Interview with Guy Stevens, Part I. sourced via http://conservationconnections.blogspot.co.uk/2012/06/manta-rays-andchinese-medicine-trade.html on the 12th of March, 2013. Still, J. (2003). Use of animal products in traditional Chinese medicine: environmental impact and health hazards. Complementary therapies in medicine, 11(2), 118-122. TRAFFIC, East Asia, (2004) Shark product trade in Hong Kong and mainland China and implementation of the CITES shark listings. Worm, B., Davis, B., Kettemer, L., Ward-Paige, C. A., Chapman, D., Heithaus, M. R., ... & Gruber, S. H. (2013). Global catches, exploitation rates, and rebuilding options for sharks. Marine Policy, 40, 194-204. Xue, C. C., Zhang, A. L., Greenwood, K. M., Lin, V., & Story, D. F. (2010). Traditional Chinese medicine: an update on clinical evidence. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 16(3), 301-312. Yi-Ming, L., Zenxiang, G., Xinhai, L., Sung, W., & Niemelä, J. (2000). Illegal wildlife trade in the Himalayan region of China. Biodiversity and Conservation, 9(7), 901918. Zhang, L., Hua, N., & Sun, S. (2008). Wildlife trade, consumption and conservation awareness in southwest China. Biodiversity and Conservation, 17(6), 1493-1516. Zhen, G. U. O. (2009). Brief Discussion in Protection and Utilization of Ethnomedicine Resources Based on Ecological Perspective. Chinese Journal of Ethnomedicine and Ethnopharmacy, 23, 001.