A Rusty Old Milk Strainer

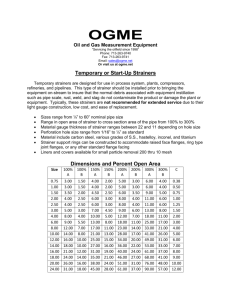

advertisement

A Rusty Old Milk Strainer: It Has Been A Long Journey Lowell L. Getz While our daughter was home this past weekend, we made a quick run to the local Walmart to pick up a few items, passing on the way the Timeless Treasures antique store in Savoy. Because Allison has an ardent affinity for old household items, she turned in for a quick look-see. Among the items on display outside the entryway was something I had not seen in almost 70 years, an old milk strainer (Figs. 1 and 2). I dare say few people entering Timeless Treasures would have recognized what that old rusty funnel-shaped object represented. But, I did and promptly entered a personal time warp. Fig. 1. Looking down into the rusty old milk strainer. Fig. 2. Milk strainer positioned on a milk can as it would have been when straining milk for sale to the “creamery.” Back in the days when most farmers kept a few milk cows to provide milk, cream, and butter for the family, as well as milk to sell for a bit of income, a milk strainer was as common a household fixture as was the ubiquitous rolling pin. The strainer was used to remove particulate contaminants that had fallen into the bucket while the cows were being milked by hand. In using the strainer, a circular “milk pad” was fitted onto the bottom of the strainer. A perforated plate was placed atop the pad to hold it flat, the plate in turn held in place by a circular ring (Fig. 3). When milk was poured into the top of the strainer, unwanted flotsam was filtered out as the milk flowed into the milk can below. Not a very sanitary process, given all the dissolved contamination that remained in the milk. Remember, however, those days were long before the current hygienic hyperbole. Fig. 3. Lower right: milk pad, composed of a layer of absorptive material sandwiched in between thin sheets of porous paper. Lower left: perforated plate that held the pad in place. Top: spring ring that held the perforated plate in place. As I looked down upon the rusty old milk strainer, vivid memories of a long distant past came flooding back. And, with them came the realization of just far I have “traveled” from where it all began, a South-Central Illinois farm in the early 1930s. The journey I have made has taken me places that were far beyond any comprehension I could have conjured up, or even understood, in those very young days. Memories, visions and other long-suppressed sensations raced through my mind, and with them the appreciation of how fortunate I have been. Things I long have taken for granted were placed in proper perspective. I have had highly successful academic and military careers, neither of which could have been anticipated when a milk strainer was a daily, albeit perverse, part of my every day life. I graduated from the University of Illinois, obtained a doctorate from the University of Michigan and had a long academic research career, beginning with eight years at the University of Connecticut, followed by 28 years at the University of Illinois. Concurrent with my academic pursuits, I managed to fit in a military career, eventually retiring as a Colonel in the Army Reserves. My current personal situation is far-removed from that I experienced during those early years. Sight of the milk strainer carried me back in time to the depths of the Great Depression. We lived in an uninsulated two-story farmhouse. Heat in winter was provided by two wood-burning stoves, a “Great Majestic” cook stove in the kitchen and a larger “Riverside Oak” heating stove in the sitting room. In winter, the unheated upstairs bedrooms were freezing cold at night, as were the downstairs rooms when we first got up in the morning. It took at least an hour for the stoves to heat up the kitchen and sitting room once the grates had been shaken down, firing up the banked, smoldering wood from the night before. Even so, the stoves barely took the chill off the room air. On especially cold nights, we would sit close to the sitting room stove with our socking feet propped up on the shiny side skirts, roasting in front and freezing on our backside. In summer, our only relief from the stifling heat was open windows. When this was insufficient to allow for restful sleeping, and it was not raining, we often slept on mattresses laid out in the yard. We had no electricity. Light for the house was provided by coal oil lamps, scarcely sufficient for reading, even when sitting up close to the lamp. Cooking was done on the wood-burning kitchen stove. There was no running water. Drinking water was carried, a couple buckets at a time, from a well over one hundred yards away, down a long hill from the house. Our wash water was obtained from a cistern that collected rainwater from the roof. Water was pumped from the cistern, by a hand pump, to a sink in the small washroom off the kitchen. Water for washing laundry and dishes and for bathing was heated on the kitchen stove. We had a battery-powered radio, use of which had to be limited. Battery life was short and money for replacements was tight. An outhouse was located about fifty feet from the back of the house. The distance seemed much longer on cold winter nights. Because of low farm prices during the Depression, our net income varied from $300-$1,500 per year, resulting in little buying power even in those days of depreciated prices. We grew or collected most of what we ate from an extensive garden for vegetables, cherry and peach trees at the end of the garden, blackberries, raspberries, dewberries, and gooseberries picked from patches in the pasture, chickens raised for meat, fish “logged” from the nearby Macoupin Creek, milk, cream and churned butter from a single milk cow, and sugar cured pork from a couple of hogs butchered during the winter. There was little money for non-essentials or “store-bought” meat, especially beef. We fattened “feed cattle” for sale, but had no means by which to preserve beef. My Mom did the laundry on a washboard in a large round galvanized washtub (which also served as our bathtub), wringing out the pieces by hand, including heavy overalls, and hanging them to dry on an outdoor clothesline. These weekly tasks were hard on her hands, especially in the cold of winter. Because I was an only child, the duties of washing the evening dishes and other kitchen utensils fell upon me. They were washed in an 18-inch diameter wash pan, the water heated on the cook stove. The order of washing was—glassware, silverware, pots and pans, and last of all, the everpresent milk strainer. By the time I got to the strainer, the water was cold, exacerbating the onerous task of removing the film of milk, as I struggled to keep the strainer in the barely larger wash pan. My young mettle was tested each night before the strainer was washed and dried. I never complained. That simply was the way of life in those days. My lot was not unique. The only thing different was that many families had a daughter who washed the dishes and had to contend with the annoying milk strainer. As the economy recovered following World War II, money became more available for non-essential commodities and life became a bit better. My parents moved twice after the war, each time to houses more modern than the one before. By then, the Federal REA (Rural Electrification Act) had extended electricity to remote farms. Electricity now lighted our house. Although exceptionally dim by today’s standards, the incandescent light fixtures were a vast improvement over coal oil lamps. We purchased an electric radio, which we could listen to as much as we wanted. We acquired a coal oil kitchen stove and coal replaced wood for the sitting room stove. My Dad bought my Mom an electric ringer washing machine, actually one that originally had been powered by a gasoline engine, which had been replaced by a small electric motor. Still we did not have running water and hot water was heated on the kitchen stove. Laundry continued to be hung to dry on an outside clothesline. There also remained the outhouse with its cold winter-night journeys. And, the cumbersome milk strainer continued to be washed by hand. After high school I was fortunate to be able to attend the University of Illinois, the first in my family to go to college. Although there were the new tribulations of writing reports and studying for exams, the dorms had “indoor plumbing.” No more cold winter trips to the outhouse. Washing the milk strainer also was a thing of the past. Both distressing annoyances began fading from my mind, accelerated by increasing demands of college life. After graduating college, I married and moved to Massachusetts to go on active duty in the Army. There we lived in modern apartments. No trips to the outhouse and no milk strainer to wash, both of which became distant memories. When my tour of duty was over, we began graduate work at the University of Michigan, where, for the first two years, we lived in apartments. All the time we were living in the apartments, we did our laundry in a small portable washer, wringing the items by hand and hanging them to dry on an outdoors clothesline. After two years in apartments, we purchased a small, winterized cabin north of Ann Arbor, where we lived the next four years. The house was heated by a fuel oil space heater that was barely able to warm the house in winter. We bought an electric ringer washer, but still had to dry the laundry on an outdoor clothesline. Thoughts of trips to the outhouse and washing the milk strainer became even more remote. Upon moving to our first academic position at the University of Connecticut, we lived in an apartment for four years. There for the first time we had an automatic washer and dryer. No more hanging out the laundry on cold winter days. We then built a modest, but comfortable, house with central heating in Storrs, in which we lived another four years. Finally, we joined the faculty of the University of Illinois and bought a new much larger, more modern, house in Champaign. For the first time we had central air conditioning. Temperatures remained comfortable throughout the house all seasons. In both houses we had automatic washers and dryers. And, we had dishwashers. No more dishes to wash by hand. From when I left the farm, each time I moved, my lot in life improved and memories of the outhouse and milk strainer disappeared more deeply into the recesses of my brain. Oh, once and awhile when socializing with friends, we would talk about the “olden days”, back when we were kids. None of our friends had grown up under such primitive conditions, as I had experienced. I tried to explain to them about winter trips to the outhouse and struggling to wash the ungainly milk strainer. Not sure they ever comprehended what life really had been like back on the farm. I would go on to say that, so long as I had an indoor bathroom (I used more descriptive terminology, not suitable for a written memoir) and did not have to wash the milk strainer, I would never complain of my station in life. Except for those brief interludes of reminiscences, however, I really did not think of the milk strainer. It took the sight of the rusty old milk strainer outside the door of Timeless Treasures to give me pause to step back and remember from whence I came. Back then, primitive conditions on the farm, while stressful, were simply the way people lived. Most of our neighbors and friends’ conditions were the same as ours. We knew no better. That just was the way it was. To ensure I never again lose sight of my beginnings and how lucky I have been, I purchased the old milk strainer. Most of the rust was removed and the strainer restored close to how it looked when a functional item so long ago. Usage and age have taken their toll on the strainer. It shows the wear and tear of straining thousands of gallons of milk and years of neglected disuse after no longer being needed. The strainer now rests on our fireplace hearth (Fig. 4), a continuous reminder of the journey I have made, a pilgrimage manifested by the presence of a rusty old milk strainer. Fig. 4. Milk strainer sitting on fireplace hearth, a daily reminder of how far I have come in life.