View/Open - Lirias

advertisement

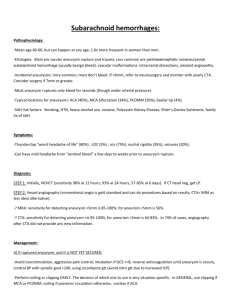

Vesalius’ experience with aortic aneurysms Raphael Suy1 , Inge Fourneau2 1 Professor emeritus, KU Leuven- University of Leuven, Department of cardiovascular diseases, Leuven, Belgium 2 Vascular Surgeon, Professor, KU Leuven – University of Leuven, Department of cardiovascular diseases, Leuven, Belgium. Key words: history, aneurysm, Vesalius, aortocaval fistula. 1 Vesalius’ experience with aortic aneurysms Introduction Andreas Vesalius was not only the central figure whose efforts most contributed to effecting an anatomical Renaissancei, he was also a clinician and a surgeon who has introduced several new surgical ideas and techniques.ii Arterial aneurysms, part of surgical pathology since early times, did also not escape his attention. Perhaps he gave it less attention at the start of his career when between 1538 and 1543 he was professor of surgery and anatomy at the University of Padua. Chirurgia Magna, a book of about 500 pages, has been published in 1568 by Prospero Bargarucci, professor at the University of Padua. This book is not the work of Vesalius but are probably by Bargarucci revised class notes of Vesalius ‘ students. It contains one short paragraph on external traumatic aneurysms.iii Vesalius’ later stay in Augsburg in 1555 is a key moment for anyone interested in the history of arterial aneurysm. This story about Vesalius’ experience with aortic aneurysms is based on a report by the doctors Adolph Occo junior (1524-1606) and Achilles Pirmin Gasser (1505-1577), who in 1555 asked Vesalius to come to Augsburg (South-Germany) to give an opinion an Leonard Welser, a gentleman with agonising and so far untreatable backpain. How could Welser’s attending physicians convince Vesalius to make a two-week iv, tiring and hazardous journey from Brussels to Augsburg? For Vesalius, the attraction to undertake such a journey were probably linked to the fame and wealth of Leonard Welser, a member of a family who were the bankers-financiers of the Habsburgempire. However, it was probably also due, in no small part to his friendship with Gasser, for the Occo familyv, and with so many other people in Augsburg, a small but important city where he spent many months between 1547 and 1551 as court physician of Emperor Charles V.vi 2 The case report of Leonard Welser. Leonard Welser died in 1557 and his autopsy was carried out under the supervision of Achilles Gasser. His medical history written up by Occo junior was reported in 1609 as “A famous case of an aneurysm”.vii The English translation of this medical history sounds as follows: About 40 years ago, my colleague, Achilles Gasser took care of Leonard Welser, a gentleman of Augsburg, who had sustained a violent concussion when handling an agitated horse. He became ill with pertinent sickness, whose principal symptom was excruciating pain in the dorsal region. He failed to respond to any of the medicines proposed by his physicians, and so the advice of Vesalius from Belgium, who then taught anatomy, was sought. This illustrious man instantly recognised the symptoms of an aortic aneurysms, which he predicted would be fatal. Immediately on discovering a small pulsating tumour under the dorsal spine, he declared it to be an aneurysm caused by dilation of the aorta. Given that this resulted from a concussion, it was incurable. He also stated, that he had seen such a disease in the neck, the chest, the popliteal space, and the arm, and that it always was associated with excruciating pain, and at the end, sideration.viii [Vesalius stated that]this condition is incurable unless it is possible to remove it, and that these aneurysms frequently contain a concrete fluid resembling ice or the crystalline humour, sometimes coagulated blood, or a polypous substance. [He also stated that] while alive, the aneurysmal blood remains fluid, but that is black and sidareted after death, [and that the] patient dies suffering from exquisite pain, [and that] sometimes these vascular dilatations form spontaneously, sometimes they are the results of an external cause, as in the present case. Two years after the consultation the patient finally ran out of patience in the face of this pain, which had resisted all medical treatment. [The patient] ultimately threw himself into the hands of an empiric [a charlatan], who administered certain catapotia [internal remedies], the use of which was soon followed by expectoration of blood causing the patient choke on his own blood, resulting in sudden death on June 25, 1557. From the section of the body we found as predicted by Vesalius, a very large, cavernous, fleshy, tumour protruding from the aorta, which was the source of the pain and the pulsations in the back. As predicted by Vesalius, the good man died from this incurable disease. The autopsy was performed on the same day by both Occos, by Ambrosius Jungius, and by Lucas Stengelius, all friends of Vesalius. The report from the autopsy reads as follows: On opening of the abdominal cavity in the usual way, the internal organs appeared to be fairly normal. There was no damage on the stomach and intestines and the liver was intact but very large, the vena cava was extremely large, larger perhaps than ever seen before in any dissection, an was ruptured at the point of contact with the aneurysm. The spleen was small and partly pale and semi-putrefied. The kidneys [appeared to be] intact. The large heart was full of blood. The aorta presented a not-moderated dilatation about the size of a hand palm, attached to ribs and dorsal vertebrae in a way that it could not be separated intact. [Once the tumour] torn apart, thin red blood flowed out which was as pure as arterial blood and surrounded by fleshy fibre free concrete; this was surrounded by a pale hard substance as thick as a finger, resembling boiled pork in colour and substance. The whole of the 3 aneurysms was about the size of a fist of a medium sized man or an ostrich egg. At the middle of the aneurysm, the ribs were almost decayed; one rib was (probably as result of very strong pressure) ruptured and broken. The vertebrae at the place where they were connected to the aneurysms, above the diaphragm were spongy and eroded so that the tip of the little finger could be inserted into their surface. [There was] nearly no stench, [and] no lesion of the lungs, and since the patient had spewed so much blood before dying it may have seemed to the bystanders that he was suffocated in that blood. The subcutaneous tissue at the level of the tumour and the pulsations during life was after death livid and suffused with blood, as in flagellants. The autopsy report was sent by Achilles Gasser to Vesalius who replied within a short period of time. The report of the autopsy and Vesalius’ answer to Achilles Gasser were preserved by Joannes Uldaric Rumler ( ?? – 1606) a grandson of Achilles Gasser,ix and published in 1668 by the good care of Georgius Hieronymus Velschius, a medical doctor and apothecary from Augsburg.x The English translation of Vesalius’ letter sounds as follows: Most learned friend, Master Achilles, I have received your letter together with a letter from Master Bartholomeus Welser, in which you describe the case of Master Leonard as it was carefully observed by you at autopsy. I am very grateful for this since I am aware that we are compelled to learn about ailments in different ways. It was very remarkable how the enlargement of an artery of this sort is mainly characterised by different types of blood clots. In this patient it resembled to lard, [but] I have found in other [aneurysms] somewhat a consistency close to the vitreous eye humour, or a fleshy substance resembling the internal surface of the ventricles of the heart. The sister of the Bishop of Arras has under the stomach in the anterior region of the abdomen a similar condition which is so mobile that you might consider it as a ball at one moment on the left side, the next on the right depending on her lying position.[She has] this condition for many years, even since her youth. The mother writes that she has perceived the beginning of this affection and that she believed that it was a pulse.xi If we frequently discover[aneurysms] in living persons, how many times may it be hidden from us in the brain, the chest or the pelvic region. May I perish if I didn’t see after my visit to Master Leonard, at least six affections of this type located in different regions. As I told you before, I have seen for the first time such an affection in the thoracic cavity near to the bottom of the neck (the jugulum), which distorted the shape of the upper ribs of the chest. The ribs and the transverse process of the vertebrae were, such as in Master Leonard, gradually shaped rather than affected by caries and putrefaction. Brussels, 18 July, 1557. Discussion Arterial aneurysm is a timeless condition. The Greek term ανεύɋίσμα, which indicates a tumour on (upon) a bloodvessel, was first recorded by Ruphus of Ephesus (110-180 AD). Galen of Pergamum, his contemporary, drew the distinction between (false) aneurysms caused by arterial trauma and genuine or true aneurysms resulting from spontaneous dilation of the whole artery at the level of the arteriovenous connections which he called αναστόμώϑείσήσ, but it remains unclear from his writings whether he had himself seen a true aneurysm.xii Prior to the 16th century the focus within medical science was often vague but in anyway, no mention was made of an aneurysm of the aorta or its side branches. This was not because aneurysms in this location were never seen as in those days post4 mortems were ‘not done’, but rather because internal spontaneous aneurysms did not exist before the 16th century. Internal aneurysms “especially in the chest or around the spleen and the mesentery where a violent throbbing is frequently observed [sic]” were first mentioned for the first time by the Sorbonne professor, Jean-François Fernel ( 1479-1558) – one of Vesalius’ teachers in Paris – in his book Universa Medicina(first edition in 1576).xiii Within a few decades this pathology took on the proportion of a plague all over Europe. The first clinical recording was written by Antoine Saporta (1507-1573), professor at the University of Montpellier, who reported in his manuscript his experience in 1554 with a pulsating tumour in a 50 years old man, next to the dorsal spine under the shoulder blade.xiv The diagnosis of aneurysm was shortly afterwards confirmed by autopsy but Saporta did not report the exact origin of the pulsating tumour and the nature of the aneurysm. The contrast with the report on Welser’s case is striking: based on a clinical examinations and on findings by autopsy in a previous similar case, Vesalius made the correct diagnosis, and also predicted the final issue since the “affection was incurable as it was related to concussion”. Two hundred years later, Joannes Baptista Morgagni ( 1628-1771), considered to be the father of pathological anatomy and the founder of modern medical diagnostics,xv called Vesalius’ diagnosis “remarkable for those days, now easy to repeat”.xvi Vesalius accounted the aneurysm of Alfred Welser on concussion of the aorta during a ride on an agitated horse. The cause of large internal and external true aneurysms remained unclear up to the 1890s. The theory of arterial-wall degeneration because of impetus of blood, concussion and exertion persisted until modern times. The truth was less convenient: in the second half of the 19th century, it became obvious that most aneurysms were related to aortitis, a late complication of tertiary syphilis. It appeared that 90 percent of patients with an aortic aneurysms suffered from syphilis, an affection whose treatment was already in the 16th century considered to be a risk factor for aneurysm formation, as first written by the famous French surgeon Ambroise Paré (1510-1590). He linked aortic aneurysms to sweat cures in patients suffering from ‘pox’, with the result that “the blood becomes greatly heated and subtilises, causing the content of the artery to seek to escape, thus producing a dilatation of the artery, at times as big as a fist”.xvii Based on the autopsy report, we can, with probability bordering on certainty, state that Leonard Welser died from massive pulmonary congestion related to overflow of blood from the aorta through the vena cava into the right ventricle and pulmonary artery. In those days, even the most learned men such as Gasser and Vesalius could not yet reach such a conclusion as Galen’s doctrine of centrifugal blood flow through arteries and through veins was still considered to be the only truth. Gasser did not mention in the autopsy report any blood in the abdomen nor around the vena cava because there was not a free rupture of the vena cava, but rather a rupture of the aortic aneurysm into the vena cava resulting in an aortacaval fistula. This explains the maximal diameter of the vena cava, the congestion of the liver, the enlargement of the heart which was full of blood, and finally, despite intact lungs, the expectoration of blood in such a quantity that it seemed to the bystanders that the patient choked in that blood. Up to the modern times internal aneurysms were incurable, but as a surgeon Vesalius was visionary by stating that cure was possible” if the affection can be resected”. Resection of external aneurysms without reconstruction was first performed in 1680 and became the procedure of choice after the introduction of inhalation anaesthesia.xviii The first attempt of reconstructive vascular surgery of an 5 aortic aneurysm, which was a luetic one, was reported in 1951.xix The title of the paper on this primary is misleading since the surgeons did not resect, but rather excluded the aneurysm, and restored the circulation by a bypass with an homograft. Three months after surgery the patient died from an abscess and an haemorraghe. The learned lesson was that cure of such an aneurysm can only be achieved by resection, as was already stated by Andreas Vesalius in 1557. Epilogue With Leonard Welser’s case in mind, and with a special interest for the history of arterial aneurysms, we can only regret that Andreas Vesalius stopped his academic career at the age of 24 years. His comment on Welser’s affection and on the autopsy report confirm that Vesalius was an excellent clinician and an innovative surgeon. Addendum Syphilitic aneurysms are saccular and mostly located on the thoracic aorta (Fig. 1). Microscopically, chronic mesaortitis with patchy destruction of musculo-elastic medial tissue and replacement by vascularized connective tissue is seen, as well as endarteritis obliterans of vasa vasorum with perivascular plasma-cell and cuffing, adventitial fibrosis and intimal atherosclerosis. XX It is hypothesized that the narrowing of the vasa vasorum causes ischemic injury of the medial aortic arch and then finally loss of elastic support and dilatation of the vessel. It is a very painful affection due to erosion of the neighbouring tissues such as nerves, bones (Fig. 2) and joints. Free rupture in the chest (Fig. 3), abdomen or even through the skin (Fig. 4) were common complications. A rupture into the vena cava was extremely rare but as deadly as a free rupture albeit a little less sudden. Several cases of death through incision by an empiric have also been reported. Syphilitic aneurysms disappeared in the first half of the 20th century with the eradication of syphilis through more hygienic life and appropriate antibiotics; the syphilitic saccular thoracic aneurysm was gradually supplanted by the fusiform abdominal so-called arteriosclerotic aneurysm which has an actual incidence of about five percent in the adult population. This new type of aneurysm is an ideal indication for surgery (endograft or replacement by a synthetic graft). i A. Cunningham (1997) p. 3. R. Van Hee (1996) pp. 141-150. iii H. Boerhaave & Albinus B.S. (1725) p. 1045. iv It took four days by continuous night and day horse riding to cover the distance of 700 kilometres from Brussels to Augsburg. (For further information read De Post van Thurn und Taxis. Brussels, 1992 p.15). v Grandfather Adolph Occo (1447-ca.1503), a Frisian, came as a doctor medicinae from the University of Ferrara to Augsburg. His adopted son Adolph, surnamed Occo II (1494-1572) and his grandson Adolph, surnamed Occo junior or Occo III (1524-1606), were close friends of Vesalius. vi H.L Houtzager (1978a) pp. 11-15. vii A. Occo III (1609) pp. 787. viii The term sideration was used to denote the sudden development of carious or gangrenous disorganization, in the ultimate stage of an acute disease. For more information read Kennedy J. (1823) p.274. ix J.O. Leibowitz (1964) pp 377-378. x J.U. Rumler (1668) pp. 46-47. xi This affection was probably a large enteric duplication in close contact with the underlying aorta . xii D. De Moulin (1961) pp. 54-55. xiii J-Fr. Fernel ( 1580) p.319. xiv A. Saporta (1624) pp. 171-172. xv S. B. Nuland (1988) chapter 6. ii 6 xvi J. B. Morgagni ( 1779) p. 370. A. Paré (1585) Livre VII, Chap. XXXIII. xviii R. M. E. Suy (2006) pp 354-360. xix C. R. Lam & H.H. Aram (1951) pp 743-752. XX H.A. Heggtveit (1964) p349. xvii Legend to the Illustrations Figure 1 Sketch of a saccular aneurysm of the aortic arch with compression of the trachea. from Hodgson J. (1815) Treatise of the Diseases of Arteries and Veins. London. Figure 2 Sketch of a saccular aneurysm of the aortic arch with erosion of the vertebrae unknown artist Figure 3 Drawing of a ruptured saccular thoracic aneurysm. From Scarpa, A. (1804) Sull Aneurisma. Pavia. Figure 4. Death by rupture of a protruding aneurysm of the ascending aorta. From Verbrugge J. (1773) De Aneurysmate. Leiden Bibliography Boerhaave, H. & Albinus B.S. (1725) Chirurgia Magna. In : Andreae Vesalii Opera Magna Anatomica & Chirurgica. Leiden. Deel II, 889-1156. Cunningham, A. (1997) The Anatomical Renaissance : the Resurrection of the Anatomical Projects of the Ancients. Aldershot, England. De Moulin D. (1961) Aneurysm in Antiquity. Arch Chir Neerl. 13: 49-63. Fernel, F-Fr.(1580) De Externis Corporis Affectibus. Liber VII in: Universa Medicina, Geneve. 319. Heggtveit, H.A. (1964). Syphilitic aortitis: a clinicopathologic autopsy study of 100 cases, 1950 to 1960. Circulation. 29:346-355. Houtzager, H.L. (1978a) De Augsburgse vriendenkring van Andreas Vesalius. Arts en Wereld, 11: 11-13. Kennedy, J. (1823) Illustrations of Rupture in the Vena Cava. The London Medical Repository. 118, vol XX, 269305. Leibowitz, J.O. (1964) Johan Udalric Rumler and a letter of Vesalius. Med Hist 85 (4): 377-378. Morgagni, J. B. (1779) Verba sunt de Lumborum Dolore. Epistola anatomica-medica XL. In: De Sedibus et Causis Morborum per Anatomem Indagatis. Liber III, 352-374. Nuland , S.B. (1988) The new medicine, the anatomical concept of Giovanni Morgagni. Chapter VI in: Doctors, The Biography of Medicine. New York. 7 Occo, A. (1609) Aneurysmatis exempla illustria. Observatio CCXI, In: Joannis Schenckii à Grafenberg Observationum medicarum rararum, novarum, admirabilium. Liber VII, 787. Lam, C.R. & Aram H.H. (1951) Resection of the descending thoracic aorta for aneurysms. Ann Surg, 134: 743752. Paré, A. (1585) De l’ aneurisme. In: Les oeuvres d’Ambroise Paré. Le 7me livre, chap. XXXIII. Rumler, J.A. (1668) Observatio Medicae. In: Georgii Hieronymi Velschii Sylloge Curationum et Observationum Medicinalium. Ulm. 46-47. Saporta, A. (1624) De Aneurysmatibus. Cap. XLII in Liber I : De Tumoribus praeter Naturam libri quinque. 167182. Suy, R. (2006) The varying morphology and aetiology of the arterial aneurysm. A historical review. Acta Chirurgica Belgica. 106: 351-360. Van Hee, R. (1996) André Vésale éminent chirurgien du XVIe siècle. Hist Sc Med tome XXX (2) : 141-150. 8