the story of poppy day: moina belle michael

advertisement

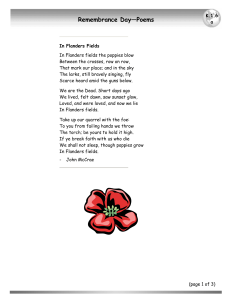

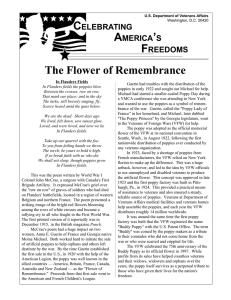

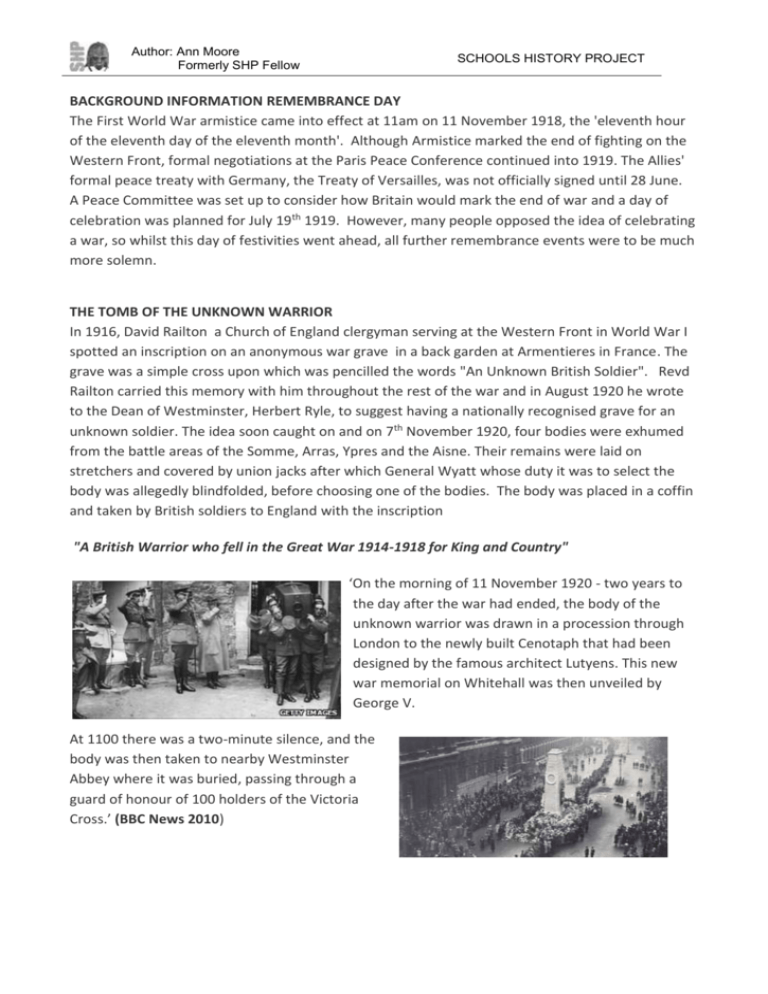

Author: Ann Moore Formerly SHP Fellow SCHOOLS HISTORY PROJECT BACKGROUND INFORMATION REMEMBRANCE DAY The First World War armistice came into effect at 11am on 11 November 1918, the 'eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month'. Although Armistice marked the end of fighting on the Western Front, formal negotiations at the Paris Peace Conference continued into 1919. The Allies' formal peace treaty with Germany, the Treaty of Versailles, was not officially signed until 28 June. A Peace Committee was set up to consider how Britain would mark the end of war and a day of celebration was planned for July 19th 1919. However, many people opposed the idea of celebrating a war, so whilst this day of festivities went ahead, all further remembrance events were to be much more solemn. THE TOMB OF THE UNKNOWN WARRIOR In 1916, David Railton a Church of England clergyman serving at the Western Front in World War I spotted an inscription on an anonymous war grave in a back garden at Armentieres in France. The grave was a simple cross upon which was pencilled the words "An Unknown British Soldier". Revd Railton carried this memory with him throughout the rest of the war and in August 1920 he wrote to the Dean of Westminster, Herbert Ryle, to suggest having a nationally recognised grave for an unknown soldier. The idea soon caught on and on 7th November 1920, four bodies were exhumed from the battle areas of the Somme, Arras, Ypres and the Aisne. Their remains were laid on stretchers and covered by union jacks after which General Wyatt whose duty it was to select the body was allegedly blindfolded, before choosing one of the bodies. The body was placed in a coffin and taken by British soldiers to England with the inscription "A British Warrior who fell in the Great War 1914-1918 for King and Country" ‘On the morning of 11 November 1920 - two years to the day after the war had ended, the body of the unknown warrior was drawn in a procession through London to the newly built Cenotaph that had been designed by the famous architect Lutyens. This new war memorial on Whitehall was then unveiled by George V. At 1100 there was a two-minute silence, and the body was then taken to nearby Westminster Abbey where it was buried, passing through a guard of honour of 100 holders of the Victoria Cross.’ (BBC News 2010) Author: Ann Moore Formerly SHP Fellow SCHOOLS HISTORY PROJECT THE STORY OF POPPY DAY: JOHN McCRAE On May 2nd 1915, a Canadian soldier Alexis Helmer, serving in Flanders, in Belgium was killed by an exploding shell at the second battle of Ypres. He was buried by his friend and colleague, John McRae who was the brigade’s military doctor. The devastation of the site had churned up the mud to such an extent, that poppy seeds which had lain dormant, were exposed to the sun once again and began to grow. John McCrae noticed that this phenomenon also happened around the newly dug graves of many of the soldiers and in memory of his friend Alexis, wrote what is probably the most famous poem of the First World War. Eye witnesses said that it took him only twenty minutes to write the poem below. In Flanders fields the poppies blow Between the crosses, row on row, That mark our place; and in the sky The larks, still bravely singing, fly Scarce heard amid the guns below. We are the Dead. Short days ago We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow, Loved and were loved, and now we lie In Flanders fields. Take up our quarrel with the foe: To you from failing hands we throw The torch; be yours to hold it high. If ye break faith with us who die We shall not sleep, though poppies grow In Flanders fields. It is said that John was dissatisfied with the poem, so screwed it up and threw it away. A fellow soldier rescued it and John, after several months of deliberations sent it to the magazine Punch, which published it anonymously on December 8th 1915. The poem became famous during the war and was published in many different newspapers and magazines. Meanwhile John was promoted to the acting rank of Colonel. On January 13 1918, he was named Consulting Physician to the British Armies in France. Sadly he contracted pneumonia on that same day, and later came down with cerebral meningitis. He died on January 28, 1918. Author: Ann Moore Formerly SHP Fellow SCHOOLS HISTORY PROJECT THE STORY OF POPPY DAY: MOINA BELLE MICHAEL Ten months later on November 9th 1918 only two days before the official armistice, a 49 year old teacher called Moina Belle Michael, was working in the Reading Rooms of the New York Headquarters of the YMCA. The annual conference of YMCA War Secretaries was going on at the same time. By chance, Moina began to read John McCrae’s poem which had been published in the ‘Ladies Home Journal’. It affected her so deeply that she did two things straight away. Firstly she went shopping and bought 25 or so red satin poppies which she handed out to conference delegates. Secondly she wrote the following poem as a response to McCrae’s by now famous poem. Oh! you who sleep in Flanders Fields, Sleep sweet - to rise anew! We caught the torch you threw And holding high, we keep the Faith With All who died. We cherish, too, the poppy red That grows on fields where valor led; It seems to signal to the skies That blood of heroes never dies, But lends a lustre to the red Of the flower that blooms above the dead In Flanders Fields. And now the Torch and Poppy Red We wear in honor of our dead. Fear not that ye have died for naught; We'll teach the lesson that ye wrought In Flanders Fields. Moina also resolved to wear a poppy every day in memory of the War Dead, and began a campaign to create the Flanders field poppy as an international sign of remembrance Within three years, she had successfully persuaded organisations in the USA, France, Canada, Australia and New Zealand to adopt the emblem. In the autumn of 1921, Field Marshal Douglas Haig lent his weight to the campaign, and the emblem was adopted by the British Legion in time for the November 1921 commemorations in Whitehall. Author: Ann Moore Formerly SHP Fellow SCHOOLS HISTORY PROJECT THE STORY OF POPPY DAY: FIELD MARSHAL DOUGLAS HAIG Field Marshal Douglas Haig is one of Britain’s best known Generals and was Commander in Chief during the First World War. His championing of poppy day and the establishment of the ‘Earl Haig Fund’ to assist ex service men, was perhaps a personal acknowledgement of the death and destruction that trench warfare brought, particularly at the Battle of the Somme? Earl Haig threw his weight behind Moina Belle Michael’s campaign, and suggested that making artificial poppies could be something that unemployed and disabled ex servicemen could do. The image on the next page is from the front cover of a small leaflet that was produced for the 1921 Remembrance Day Service and was owned by the wife of Second Lieutenant Leonard Brown who died serving with the East Surrey Regiment in Flanders in 1918; after nearly four years on the Western Front, having been commissioned from the ranks. Author: Ann Moore Formerly SHP Fellow Acknowledgements: http://www.20thcenturylondon.org.uk/ www.greatwarphotoswordpress.com www.greatwar.co.uk Wikipedia BBC History BBC News London Museum Melbourne Museum Australia SCHOOLS HISTORY PROJECT