Brooke Hunter Department of History BRIDGE

advertisement

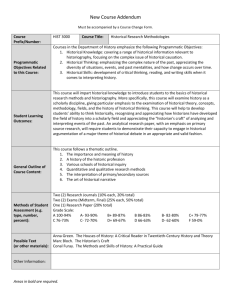

Brooke Hunter Department of History BRIDGE Final Report 2009-2010, 2013 (update) HIS 360: Seminar in Historiography This is an advanced seminar for History majors taken during the junior year designed to prepare students for our research capstone. This seminar provides an intensive exploration of historiography (i.e., the study of the study of history including interpretation and methodology). I have taught the course at least once a year for nine years. Problem/Question When I started the course could best be described as an advanced reading seminar. I selected three themes/topics and had the students read a lot of scholarship and write reviews. This graduate seminar format did not work well with undergrads who lacked the necessary skills and stamina for such intense discussions. I also recognized that most students were not doing serious research in the capstone. It occurred to me that giving students practical experience using a variety of historical methods was as important as teaching them to read more critically in the junior seminar. It’s too late by the time they’re in the senior research seminar to learn much about methods. So, I have revised the course to combine these two skills: reading scholarship and doing history. Despite an increasing focus on methodology the central purpose of this seminar is to develop a student’s ability to read and evaluate historical scholarship at a higher level. This means not only identifying and evaluating the thesis (does the evidence support the author’s claims), but also recognizing the author’s purpose and methodology, situating the work in the larger body of scholarship and using the work to provide ideas for further research. This kind of critical reading is required for students to produce new historical knowledge in the capstone. Yet students struggle with the basic identification of these key elements of historical scholarship. As a result, our discussions rarely get beyond articulating the thesis. How can I teach students to “read like a historian” more effectively? (i.e., identify historical arguments, situate a work in its historiographical framework, and classify methodology/approach).1 1 I am not alone in facing this problem. See, Craig T. Nelson, “On the Persistence of Unicorns: The Trade-Off between Content and Critical Thinking Revisited,” in Bernice A. Pescosolido and Ronald Amizade, eds., The Social Worlds of Higher Education: Handbook for Teaching in a New Century (Boston: Pine Forge Press, 1999), 168-184. On historians’ reading strategies, see Sam Wineburg, Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts : Charting the Future of Teaching the Past (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2001), 63-112. 1 2009-2010 PROJECT 1. Methods Journal (informal writing). Gauge student understanding and target specific skills needed to write a book review. Assessment: effort, thoughtfulness, accuracy Book Review (formal writing). Put practice to the test. Assessment: ability to summarize argument; situate in historiographical context; evaluate. Modeling Critical Reading in discussion (e.g., breaking introduction into ‘sections’ by purpose; identifying key terms and phrasing ( historiographical “flags”), using endnotes to evaluate argument and use of evidence) Scaffolding/sequencing [journal entries/discussion topics: 1) identifying and summarizing argument, & historiographical framework (purpose); 2) identifying and evaluating approach/structure; 3) asking historiographically-derived questions.] In-class group work (e.g., charting an argument/evaluating evidence) 2. Evaluation Journals keep students on top of reading, while sequencing helps focus on specific skills. In-class group work provides a change of pace. However, historiography is not represented in sequence (part of discussion but not hands-on practice). Structural issues: Since I don’t read them ahead of time (collect in class), I lose the chance to shape seminar discussion around issues raised in entries and trouble-shoot problems. Having students correct their work in class would be a way to correct this problem. In their book reviews students identified the thesis (because we repeated it every class). Their summaries could better describe the author’s “road map” (i.e., How is the big argument arranged into little arguments?) and use of evidence. Historiographical discussions were weak. Students clearly need more practice/preparation. I should add a journal entry (identify historian’s motives and purpose for writing). I might also consider breaking the book review assignment down into parts: summary, historiographical context, evaluation. It may also work better to have students write a review first that focuses on summary and evaluation of the argument. The next step (newer skill) would be to analyze the work’s historiographical context. A pre- and post-test using reading we have not discussed might be a better way to generate an accurate reading of progress. 3. Results/Reflection My BRIDGE project and participation in the TFLO Capstone Competencies Assessment Pilot Summer 2011 contributed significantly to my Department’s Self-Study (2011-2012), which resulted in a major revision of our curriculum and renumbering of our courses effective Fall 2013. Our goal is to improve our major by building skills purposefully from the 100 level to the capstone. The historiography seminar, renamed The Craft of History and renumbered HIS 260 will now be recommended for second semester sophomores and for juniors. This shift is designed to help students apply reading and analytical skills learned in the seminar to their advanced course work. This seminar and the research seminar (HIS 460) are being changed to topical courses. This will take better advantage of faculty expertise and increase 2 student achievement. Finally, a key problem that I voiced to my BRIDGE colleagues was the fact that students’ exposure to historiography outside the seminar was too limited. We have addressed this problem with criteria for each level ensuring that historiography will be introduced early and reinforced often as students complete the major.2 2013 PROJECT 1. Methods In hopes of figuring out where students’ abilities were at more accurately I gave them pre- and posttests in which they read a scholarly work and were asked to identify the basic elements. Pre-Test (January 28, 2013). This was delivered on the first day of class following a brief introduction to the course. Since time was limited students were only given the introduction and conclusion (5 pages) to a recent scholarly article to read and asked to identify the topic, purpose/historiographical contribution, thesis, and methods/approach. I asked them to mark the text and collected it as well. (Appendix A) Each response was evaluated on a 4-point scale (0=no mastery, 1=limited, 2=satisfactory, 3=excellent). Post-Test (April 22, 2013 & May 6, 2013). Students completed an 800-word article review (Appendix B) for a work we had not discussed yet to check their progress in “reading like a historian”. Students were evaluated on the 0-3 scale. Scaffolding Assignments: Précis (Appendix C) and Article Analysis Worksheets (Appendix D). These assignments were used to emphasize particular skills and improve student ability to “read like a historian”. 2. Evaluation On course evaluations students rated their knowledge of historiography before and after taking the course. Prior to the seminar two students rated their knowledge at “none” and ten as “basic”. After completing the course eight rated their knowledge as “good” and four as “high”. When asked where and how they had learned about historiography in other courses, student responses varied from “I had no idea what historiography was prior to this course”, “never heard it”, “I searched it before taking the course, but not really any mention in other classes” to “I’ve heard professors mention it on topics they’ve studied but I’ve never had to incorporate it into my own work” and “in other courses we have talked about some of the debates within historiography.” 2 These changes are supported by recent scholarship, see Laura M. Westhoff, “Historiographic Mapping: Toward a Signature Pedagogy for the Methods Course,” Journal of American History 98, no. 4 (March 2012): 1114-1126; Kathleen W.Jones, Mark V. Barrow Jr., Robert P. Stephens , and Stephen O’Hara, “Romancing the Capstone: National Trends, Local Practice and Student Motivation in the History Curriculum Journal of American History 98, no. 4 (March 2012): 1095-1113; Linda J. Borish, Mitch Kachun, and Cheryl Lyon-Jenness, “Rethinking a Curricular ‘Muddle in the Middle’: Revising the Undergraduate History Major at Western Michigan University,” Journal of American History 95, no. 4 (March 2009): 1102-1113; Forum on Capstone Courses in Perspectives (April 2009). 3 Pre- & Post-Test : “Reading Like a Historian” For this discussion I have isolated two elements: 1) identifying the historiographical framework, 2) identifying the thesis. While students could not define historiography well on the first or last day of class, Figures 1 and 2 suggest that identifying the thesis is a bigger problem. Two-thirds of the students failed to articulate the thesis on the pre-test, while one-third of the students still failed to identify the thesis on the post-test. Several students confused historiographical claims with the argument on both the pre- and post-tests. Figure 1: Historiography 9 8 7 6 5 # of students 4 3 2 1 0 Pre-Test Post-Test 0 no competency 1 1+ minimal 2 2+ satisfactory 3 excellent Figure 2: Identifying the Thesis 8 7 6 5 # of students 4 Pre-Test 3 Post-Test 2 1 0 0 no competency 1 minimal 1+ 2 2+ satisfactory 3 excellent 4 Tracking individual students is also revealing. While the class as a whole improved, several individuals demonstrated no growth or declined (as shown in Figure 3). Some, like student E who scored excellent in both categories on the pre- and post-test, had nowhere to go. But why did the four students who scored “no mastery” or “satisfactory” in historiography on both tests not improve? Why did high-scoring students (C, G) perform at a lower level on the post-test for identifying the thesis and others remain at “no mastery”? These results suggest a problem with the scaffolding assignments. Figure 3: Student Pre-Test Post-Test +/- Pre-Test historiography Post-Test +/- thesis A 1 3 + 1 2 + B 1 1 same 0 1 + C 2 2 same 3 2 - D 2 1 - 1 1 same E 3 3 same 3 3 same F 2 3 + 1 3 + G 2+ 3 + 3 2 - H 2 2 same 1 1 same I 2 2 same 1 1 same J 3 3 same 1 2 + K 3 3 same 2+ 3 + 2 3 + 1 3 + 3 ? 3 ? L M n/a n/a Student reading practices may also offer some answers. I noted on the pre-test that students underlined text without making marginal notations indicating the significance. Since I gave students a list of things to look for more probably made more notations than usual. (Appendix A) I made a big point throughout the semester to encourage students to read actively either marking the text or taking notes. I did not get much traction. One obstacle is that many students rent their books, which prohibit marking. However, students will never “read like historians” if they don’t change their habits. Students completed two article worksheets during the semester, which is clearly not enough (Appendix D). Only a few students performed well on the table section which asked them to break the argument down into smaller parts, identify evidence, and evaluate both argument and evidence. They learned that it’s hard work to “read like a historian”, but most are not putting in the necessary effort except when they are required to do so by an assignment (and even then the results are mixed). 3. Results/Reflection As our Department implements our new curriculum it is critical that we follow through and introduce historiography and give students practice “reading like historians” in every course and not just in the seminars. As I noted in 2010 it might be best to isolate particular skills and then put them together to 5 avoid overwhelming students as they learn. We need to design and share assignments that address these skills. Only through repetition and practice will “reading like a historian” become a habit of mind for our majors. As I continue to work on improving students’ ability to identify historiographical claims and arguments, it is also critical that we address students’ weaknesses in other areas such as recognizing research questions (an excellent clue to those elusive thesis statements!) and evaluating a historian’s argument and use of evidence. Appendix A: Pre-Test Read the introduction and conclusion of: Rachel B. Herrmann, “The ‘tragicall historie’: Cannibalism and Abundance in Colonial Jamestown,” William and Mary Quarterly, 68, no. 1 (October 2011): 47-74. Mark the article as you read. Identify the following: topic under investigation purpose for writing (why is this work important?) references to other historians (where does her work fit into existing literature?) method or approach to the topic (how is her study designed? how does she use sources?) thesis (what is her research question? The argument is the answer to that question.) 1. What is the topic under investigation? 2. What is the purpose of her research? How is her approach or method unique? Where does she state this most clearly? (cite page #) 3. What is her argument? Where does she state this most clearly? (cite page #) 6 Appendix B: Post-Test Learning Objectives: To identify the main components of a piece of historical scholarship (i.e., argument, historiography, methodology, evidence). To build historical literacy skills: (1) read for content to learn about history, (2) read to analyze the author’s purpose and interpretation to learn about historiography, (3) to evaluate a historian’s argument and use of evidence. To track your progress in these skills from the beginning of the semester Reading Questions: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. What is the specific topic under investigation? What is the broader subject? How does the author summarize and synthesize existing scholarship on Prohibition? How does the author fit their work into the historiography? What new contribution is made? What is the author’s main argument? What is the author’s method or approach? What are the key sources used? How do you know? Is the article divided into sub-sections? If so, what is the subject of each section and how does it support the main argument? Is the evidence convincing? Review: The review should be 800 words or less, typed and single-spaced (please double-space between paragraphs). Do not include heading or citations in your word count. Proofread your final copy carefully and make corrections. Use footnotes or endnotes in Chicago style. You must use abbreviated citations for subsequent citations. 1. Summarize a historian's argument and methodology. The ability to summarize other scholars’ interpretations is a central skill for a historian, but writing an effective summary is challenging. An effective summary identifies the author’s research question, states the thesis clearly, and elaborates on how the thesis is supported (methods), citing selected sections that illustrate the author's main point. 2. Historiography: document a historian’s scholarly contribution. Where does the work fit into existing scholarship, and, what scholarly contribution has been made to the field or debate? As a beginning researcher you may feel that you lack the experience and knowledge to make such judgments. But a careful review of the article should enable you to comment on many aspects of a scholarly work. Focus on the author's aims/claims as stated in the introduction and notes. 3. Critique: offer some critical insight about the work. Being critical does not mean being negative; include both positive and negative features as appropriate. Focus on whether the thesis is supported by the evidence. Has the historian convinced you their interpretation is correct? Use specific examples to support your claims. Do not neglect the notes!! 7 Appendix C: Précis The ability to summarize other scholars’ interpretations is a central skill for a historian. Write a 250word précis of Shy's essay. A précis is a summary in which the author’s argument is accurately and fairly reproduced, but in your own words. The purpose is to demonstrate comprehension of the material not to critique it. Try not to quote the text but if you do make use of key phrases rather than complete sentences. Block quotes (three lines or more) are absolutely forbidden. You should cite quotes as well as paraphrasing of main ideas and presentation of evidence using parenthetical citations, e.g., (34). Cite the essay using Turabian/Chicago Manual of Style. Appendix D: Article Worksheet 1. Author, title of article: 2. Historical subject (broader) and theme (narrower) of this article? 3. Historical question(s) addressed in this article? 4. Thesis or argument of this article? 5. Historiographical significance? What scholarly contribution has the author made? 6. What types of sources does the author use, and how are they used to support an argument? 7. Could the same evidence support a different conclusion? 8. Is the argument weakened by questionable or inadequate evidence? What makes it questionable? Why is it inadequate? 9. Can the conclusions of this study by generalized? If so, how far? If not, why not? 10. Complete the table below. Add rows if needed. Section Main Ideas Evidence (not just the source) Comments about evidence or approach Introduction Conclusion Section 1 Section 2 Section 3 8