Impact of Gender on Leadership

advertisement

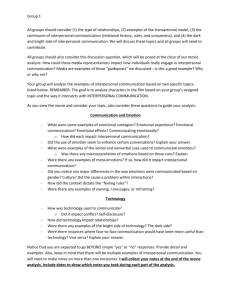

Running head: GENDER AND LEADERSHIP The Impact of Gender on Leadership Shayna Cooke Virginia Commonwealth University 1 GENDER AND LEADERSHIP 2 The Impact of Gender on Leadership When looking at the majority of top management positions within companies, mid-size to large, it is safe to say that men, rather than women, have predominantly managed these organizations. As a matter of fact, Zenger & Folkman (2011), the authority in strengths-based leadership development, conducted a research study, sampling 7,280 leaders (64% male and 36% female), on their leadership effectiveness in 2011. What they found was very interesting. Of the 7.280 individuals in leadership positions at their companies, 78% were male and only 22% were female. These numbers indicate that there is still a vast gender gap in terms of leadership positions held by women across the board, from sales and marketing to administrative and clerical work. However, looking at the leadership effectiveness index on this same population sample, it was determined that overall, females were rated consistently more positively than males by the total of all respondents of this survey, from the manager to peers. This data indicates that while women hold fewer leadership positions within these companies and across these divisions, the consensus on female leadership is overwhelmingly positive. So, what is it about female leadership that is so effective? Judy Rosener (1990) believes that women make more efficient leaders because they tend to characterize their leadership style as transformational, getting their subordinates or direct reports to transform their own self-interest into the interest of the group or company and turn their concern outward toward the mission of the organization, rather than focus on their own personal successes. Wilfred Drath (2001) would label this kind of leadership as Interpersonal Dominance. Drath (2001) explains that when working from a place of Interpersonal Dominance, a leader has insight into the vision and the direction of the company and can motivate people to then become focused on this same mission and vision of the company through persuasion and shared commitment to the organization. Rosener (1990) calls this GENDER AND LEADERSHIP 3 leadership style interactive leadership because she believes that through this transformational type of leadership, women work consistently to make their interactions with subordinates or direct reports positive for everyone. Women do this by encouraging participation in the decision making process, by sharing power and information amongst the employees collectively rather than keeping them in the dark, and help by enhancing employee self-worth through positive meaningful interactions. All of these strategies and interactions help to ignite a passion and sense of loyalty with personnel, which is beneficial for the employee but also for the organization. This type of leadership style became more popular as more women began to take on leadership roles within their organizations. Until the 1960s, it was not common for a woman to be career oriented and career focused. The expectation of the woman’s role in the family and society was one that expected women to be wives, mothers, volunteers in the community, nurses in the medical field, and, school teachers (Rosener, 1990). These roles taught women to be cooperative and supportive of those around them. To be understanding and gentle when providing service to other people. This type of gentle leadership and collaboration, according to Drath (2001), focused on Influence and Dialogue, but rarely reflected Dominance. Through Influence and Dialogue, women were able to lead through collective collaboration that allowed women to influence others more than she was influenced and to do that by establishing a gentle dialogue in shared work. Rosener (1990) hypothesized that men have always had to appear to be competitive, strong, decisive and in control, while women have been permitted to work from a place of collaboration. Drath (2001) would describe this type of leadership for men as Personal Dominance, where the leader embodies the direction of the company and heavily encourages others to follow his lead, not through a collaborative effort which focuses on the “why” of the GENDER AND LEADERSHIP 4 organization, but through a commitment to the leader, reflected from this personal dominance establishment of leadership. Through the survey, conducted by Zenger & Folkman (2011), it was discovered that the bias of most people surveyed is that females are more successful at nurturing competencies that enhance relationship building and the development of other employees. While these characteristics are not specifically reserved for women, it is more common to see women working from an interpersonal and relational place that focuses on others, rather than their selves (Drath, 2001). Interpersonal leadership practice involves negotiating ones influence over others and the way in which to move the direction of the company forward using this interpersonal influence. In terms of relational focus, this leadership style focuses on the meaning of the organization and not only allowing others to see that meaning but to help them to align their focus in that way as well (Drath, 2001). Figure 1 (below) describes Drath’s (2001) leadership principles and how they emerge from understanding leadership and putting that understanding into practice. Drath (2001) established a Personal Dominance Principle which indicates that the leader embodies direction, inspires commitment, and personally faces adaptive challenges successfully. This leadership principle rings true with the command and control type of leadership that is experienced from a top-down or captain type of leadership. Though woman can most certainly lead from this angle, it is not as common to see women working from a personal dominance leadership style. Rosener (1990) suggests that women are more successful utilizing a non-traditional form of leadership such as Interpersonal Dominance as seen on Drath’s figure of Leadership Principles. GENDER AND LEADERSHIP 5 Figure 1. Drath’s Leadership Principles Ways of Understanding Leadership Ways of Practicing Leadership Personal: Leadership is a personal endowment of leaders. Interpersonal: Leadership is a process of negotiating social influence Dominance: Leadership happens when a leader acts Personal Dominance Principle: The leader embodies direction, inspires commitment, and personally faces challenges The leader has insight into direction, motivates people to become committed, and facilitates the facing of challenges. Influence: Leadership happens when a person influences others more than he or she is influenced. Influence is recognized as a tool the leader may use to gain agreement or compliance Dialogue: Leadership happens when people make sense together of shared work. Dialogue is recognized as an intimate approach to communication Dialogue is Interpersonal influence: A leader recognized as emerges from perspective taking, reasoning and reframing, suspending negotiating as the assumptions. person with the most influence over direction, who is thus best able to gain commitment and create conditions for facing adaptive challenges. Relational: The leader is the Differences in relative Relational Dialogue Leadership is meaningcentral participant influence are products Principle: People making in communities of in the communal of the communal sharing work create practice construction of construction of the leadership by direction, meaning of direction, constructing the commitment, and commitment, and meaning of direction, facing adaptive facing adaptive commitment, and challenges. challenge. adaptive challenges. Figure 1. Drath’s Leadership Principles as described in The Deep Blue Sea: Rethinking the source of leadership. Interpersonal influence Principle occurs when a leader emerges organically from collaborative teamwork as the person with the most influence over direction. This person is then GENDER AND LEADERSHIP 6 best able to gain commitment from the team in moving forward (Drath, 2001). Per this description, it should be noted that both male and female leaders have the ability to work from this frame and do so successfully. Drath (2001) suggests that the final Leadership Principle, Relational Dialogue, where people share work and in turn create leadership by expressing and building on the meaning of direction and commitment to the team, is rarely attainable by anyone and reserved for the most enlightened and successful leader. While these Leadership Principles, supplied by Drath (2001), are succinct and helpful in determining ones strengths as a leader. Rosener said it best when she said, “the best leadership style depends on the organization context”(Rosener, 1990, p.125). The best leaders are those that are fluid in their use of leadership skills, adaptable to a variety of situations, and can modify their leadership tactics based on the scenario at hand. Though female leaders seem to be more comfortable, and more common, at working on leadership and management from a transformational and collaborative approach, this would not always work, depending on the situation. Just as the personal dominance or top-down approach, most often used by men, will not work in every situation. As a woman, the Observer also feels more comfortable working from a place of collaborative and supportive leadership, inspiring from within. When looking at Figure 1, the Observer identifies most closely with Interpersonal Dominance as her most comfortable description of leadership, per Drath. But, as noted above, the Observer also must be able to adjust her style to be reflective of the audience and the situation. To be an effective leader and have the ability to manage a team successfully, one must be able to read the people and the situation in which they find themselves and react in a strong and decisive way that suits the GENDER AND LEADERSHIP situation but still instills a sense of calm amongst the employees and direct reports. When one can adapt this type of leadership fluidity, then they can be considered a successful leader. 7 GENDER AND LEADERSHIP 8 References Drath, W. (2001). The deep blue sea. Rethinking the source of leadership. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Rosener, J. (1990). Ways women lead. Harvard Business Review, 119-125. Zenger & Folkman. (2012). A study in leadership: Women do it better than men. (Strengths based leadership development). Orem, UT: Retrieved from Zenger Folkman website: http:// www.zengerfolkman.com