The Anthropology of Adventure

advertisement

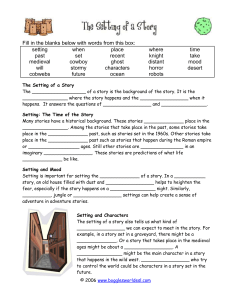

The Anthropology of Adventure: Moving Beyond Ambivalence? Proposal for an Annual Reviews of Anthropology Article February 2009 Luis A. Vivanco, Associate Professor of Anthropology, University of Vermont and Robert Fletcher, Assistant Professor of Natural Resources and Sustainable Development, University for Peace Overview The proposed article, of approximately 7000 words and 150 references, explores the empirical explosion of popular interest in adventuring, dominant social and cultural theories of adventure, anthropology’s historically ambivalent relationship with adventure, and new directions for anthropological research on adventure. Below is a brief outline and abstract to give a sense of the substantive issues that would be covered in this article. Brief Outline A. Introduction B. Explaining Adventure: What Is It and Why Do People Do It? Overview of dominant theories of adventure C. Anthropology’s Ambivalence towards Adventure Historical exploration of anthropology and/as adventure D. Moving Beyond Ambivalence Discussion of new currents in anthropology, as well as future directions Abstract Introduction In the past several decades, the practice of adventure has exploded worldwide, as evidenced by dramatic growth and popularization of adventure tourism and “extreme” sports. Consumer culture celebrates the adventurer, producing narratives about spectacularly successful—and, often more attention-grabbing, spectacularly failed—adventures. This also promotes the consumption of goods meant to capture, or more to the point, generate, a sensibility for adventure, from outdoor magazines to Hummer SUVs. Concurrent with this growth in adventure practice and sensibility has been increasing interest from a variety of academic perspectives to explain this attraction to adventurous activities. Although anthropology has only recently begun to contribute to this literature, due in part to a longstanding ambivalence towards adventure within the discipline, we suggest that anthropologists occupy a unique position in the academic division of labor and can productively contribute to the analyses of adventure in a variety of ways. Indeed, a number of anthropologists have already furthered discussion of adventure in important ways, and this initial work could be reinforced through subsequent research. Adventure touches on issues central to current anthropological interests, including themes of experience, representation, and political economy as they relate to topics such as tourism, consumer culture, media, colonialism, and the history of anthropology. In this review, we offer an overview of the rapidly growing literature analyzing adventure, identify anthropologists' own contributions to this literature, and describe new ways in which anthropologists have begun, through their particular methods (ethnography) and subject matter (cross-cultural comparison), to engage with adventure-related research. Explaining Adventure: What Is It and Why Do People Do it? The primary idioms of adventure in Western culture are biological, ranging from the biochemical—references to the “adrenaline rush” and “endorphin high” abound—to the evolutionary (Vivanco and Gordon ibid.; e.g., Ardrey 1976; Campbell 1968; Manhart 2005). Others have suggested that a quest for adventure is inherent to only some people, who are hardwired to need higher levels of stimulation that the average individual in order to achieve "optimal stimulation” (e.g., Zuckerman 1979 2007). Some have suggested that adventurers suffer from psychological pathology such as neurosis or addiction (e.g., Farberow 1980; Ogilvie 1973). Others describe motivation in terms of the pursuit of valued goals. In this vein, it is commonly pointed out that adventure activities tend to precipitate an altered state of consciousness alternately called "flow" (Csikszentmihalyi 1990), "peak experience" (Maslow 1961), "edgework" (Lyng 1990) and "action" (Goffman 1967). Even while pointing usefully to the connections between human biology and adventure, the reduction of adventure to its evolutionary and biochemical functions and manifestations greatly obscures the social, cultural, political, and economic contexts that shape how and why people think of certain activities and images as adventuresome (Vivanco and Gordon 2006). In a different vein, then, some researchers have described the unique characteristics designating adventure as a particular activity or sensibility (Campbell 1968; Celsi et al. 1993; Simmel 1971; Vester 1987; Zweig 1974). Others have explained adventure motivation in terms of collective dynamics, viewing the pursuit of adventure as a "performance" in which adventurers act out culturally-valued "models or scripts" (Celsi et al. 1993; Jonas 1999; Vester, 1987). A popular line of sociological research describes the pursuit of adventure as a form of escape from or resistance to unsatisfactory aspects of mainstream social life (Arnould et al. 1999; Celsi et al. 1993; Lyng 1990, 2005; Mitchell 1983; Vester 1987). In addition, a growing literature investigates the demographics of adventure practice, seeking to explain the widely-noted fact that the majority of adventure athletes and tourists tend to be white, upper-middle-class members of advanced industrial societies (e.g., Braun 2003; Fletcher 2008; Gibson and Yiannakis, 2002; Kay and Labarge 2004; Kusz 2004; Simon 2002, 2004). Adventure has been analyzed from a variety of other angles as well. A substantial body of research explores the risks, difficulties and potential contradictions involved in the commercialization of adventure, that is, in offering an inherently predictable activity as a touristic experience that can be purchased in advance (e.g., Cater 2006; Holyfield 1999; Ortner 1999; Palmer 2006). Researchers have explored legal issues surrounding the rise of adventure activities as well (Simon 2002). As a field dominated by psychologists and marketing researchers, the majority of adventure research to date has involved interviews, surveys, and other forms of formally structured methodology. In addition, research analyzes texts written by travelers, explorers, journalists, and other adventurers. There has, however, been substantial ethnographic research of adventure as well, undertaken by anthropologists and others, concerning such sports as skydiving (Celsi 1993; Celsi et al. 1994; Lyng and Snow 1986; Lyng 1990), hang gliding (Brannigan and McDougall 1983), mountaineering (Mitchell 1983; Thompson 1984), rock climbing (Abramson and Fletcher 2007), whitewater kayaking (Kinney 1997; Fletcher 2008) and rafting (Arnould and Price 1993; Arnould et al. 1999; Fletcher 2008; Holyfield 1999; Jonas 1999), and cliff jumping (Abramson and Laviolette 2007). Anthropology’s Ambivalence towards Adventure Until recently, anthropologists have been conspicuously absent from these debates. Perhaps this reticence is due to an "ambivalence to adventure," which as Vivanco and Gordon (2003, p.11) observe, is related to a longstanding conviction within the field "that science kills adventure, our claims to fieldwork and forms of writing meant to distance us from the self-referential pursuits of adventurers." In Tristes Tropiques, for instance, Lévi-Strauss (1973 [1955], p.17) famously remarked, "Adventure has no place in the anthropologist's profession; it is merely one of those unavoidable drawbacks, which detract from his effective work." On the other hand, there is little doubt that anthropology’s public identity is intertwined with adventure, a fact relevant long before the likes of Indiana Jones came along. Franz Boas himself is reported to have been drawn to anthropology through its association with adventure (Pierpont 2004). Many contemporary anthropologists will admit that it was a similar desire for adventure that attracted them to the discipline, a sensibility very much framed by mass media images produced in magazines like National Geographic or Hollywood spectacles like Lawrence of Arabia. This ambivalence toward adventure offers a useful vantage point from which to consider key aspects of disciplinary history, especially its normalization as a professional field, shaped in relation to (often in differentiation from) adventurers and adventuresome experiences. Moving Beyond Ambivalence As anthropologists have begun to analyze adventure as a form of social action and cultural logic, they have contributed to the various discussions outlined above in various ways that could be elaborated upon in future research: 1) While adventure has been described as a universal human inclination, as described above, cross-cultural research has called into question whether something that can be commonly labeled as adventure is actually practiced in societies around the world (Ridgeway 1979; Fisher 1990; Ortner 1999; Rubenstein 2006) and future study could explore this issue further. 2) As a form of “deep play” (Abramson and Fletcher 2007), the pursuit of adventure seems to challenge rational actor explanations of human behavior, but can such theories recapture this phenomenon, for instance, by describing it as a form of “costly signaling” (Manhart 2005)? 3) While a few studies have investigated adventurers' assessment of risk (Lyng 1990; Hunt 1995), more work, drawing on anthropological research concerning assessment of risk crossculturally (e.g., Douglas 1992; Douglas and Wildavsky 1983), is definitely warranted. One approach would be to investigate, in the tradition of Malinowski (1954) and Gmelch (1992), the pseudo-magical rituals adventurers use to attempt to gain control over inherently unpredictable circumstances. 4) Colonial-era and contemporary adventuring have often been organized around the production and consumption of written and visual narratives, suggesting an exhibitionary logic underlying the conceptualization and practice of adventure (Vivanco and Gordon 2006). The recent volume Tarzan was an Ecotourist…And Other Tales in the Anthropology of Adventure (Vivanco and Gordon 2006) shows how such themes intersect with long-standing anthropological interest in representation and the political economy of meaning production, and this work could be built upon in the future. 5) Many adventurers describe their activities as ineffable, indescribable, claiming that only someone who has undertaken the experience can truly understand the appeal (Lyng 1990). Thus, there appears to be important knowledge concerning the adventure experience only accessible via the type of involvement that participant observation affords, and thus anthropologists are uniquely situated to explore this knowledge. 6) And yet there remain sources of ongoing ambivalence for anthropologists working on adventure as a subject of study, which have to do with the institutional constraints placed on ethnographic research, as well as shifting notions of ethnographic authority (Stoll 2006). Future work might explore how this ambivalence can be negotiated in the production of adventure ethnographies. References Abramson A, Fletcher R. 2007. “Recreating the vertical: Rock climbing as epic and deep ecoplay.” Anthropology Today 23(6):3-7. Abramson A, Laviolette P. 2007. “Cliff-jumping, tombstoning and coasteering: Notes on a mutating British landscape and an emergent dangerous game.” Journal of the Finnish Anthropology Society 32(2):5-28. Arnould EJ, Price LL, Ontes C. 1999. “Making consumption magic: A study of white-water river rafting.” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 28:33-68. Arnould EJ, Price LL. 1993. “River magic: Extraordinary experiences and the extended service encounter.” Journal of Consumer Research 20:24-45. Ardrey R. 1976. The Hunting Hypothesis. New York: Atheneum. Braun B. 2003. “‘On the raggedy edge of risk’: Articulations of race and nature after biology.” In Race, Nature, and the Politics of Difference, ed. DS Moore, J Kosek, A Pandian, pp. 175203. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. Brannigan A, McDougall AA. 1983. “Peril and pleasure in the maintenance of a high risk sport: A study of hang-gliding.” Journal of Sport Behavior 6:37-50. Campbell, J. 1968. The Hero with a Thousand Faces, 2nd ed. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Cater CI. 2006. “Playing with risk? Participant perceptions of risk and management implications in adventure tourism.” Tourism Management 27:317-325. Celsi RL. 1992. “Transcendent benefits of high-risk sports.” Advances in Consumer Research 19:636-641. Celsi RL, Rose RL, Leigh TW. 1993. “An exploration of high-risk leisure consumption through skydiving.” Journal of Consumer Research 20:1-23. Csikszentmihalyi M. 1990. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York: Harper and Row. Douglas M. 1992. Risk and Blame: Essays in Cultural Theory. London: Routledge. Douglas M, Wildavsky A. 1983. Risk and Culture: An Essay on the Selection of Technological and Environmental Dangers. Berkeley: University of California Press. Farberow NL, ed. 1980. The Many Faces of Suicide: Indirect Self-Destructive Behavior. New York: McGraw-Hill. Fisher JF. 1990. Sherpas: Reflections on Change in Himalayan Nepal. Berkeley: University of California Press. Fletcher R. 2008. “Living on the edge: The appeal of risk sports for the professional middle class.” Sociology of Sport Journal 25(3):310-330 Gibson HJ, Yiannakis A. 2002. Tourist roles: Needs and the lifecourse. Annals of Tourism Research 29(2):358–383. Gmelch G. 1990. “Baseball magic.” In Conformity and Conflict, ed. J Spradley, D McCurdy, pp. 373-383. Glenview, IL: Scott, Foreman/Little, Brown. Goffman E. 1967. Interaction Ritual: Essays on Face-to-Face Behavior. Garden City, NJ: Doubleday. Holyfield L. 1999. “Manufacturing adventure: The buying and selling of emotions.” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 28(1):3-32. Hunt JC. 1995. “Divers’ Accounts of Normal Risk.” Symbolic Interaction 18:439- 462. Jonas LM. 1999. “Making and facing danger: Constructing strong character on the river.” Symbolic Interaction 22:247-267. Kay J, Laberge S. 2004. “Mandatory equipment”: Women in adventure racing. In Understanding Lifestyle Sports, ed. B Wheaton, pp. 154–174. New York: Routledge. Kinney TD. 1997. Class V Whitewater Paddlers in American Culture: Linking Anthropology, Recreation Specialization, and Tourism to Play. M.A. Thesis, Northern Arizona University. Kusz K. 2004. “Extreme America: The cultural politics of extreme sports in 1990s America.” In Understanding lifestyle sports, ed. B Wheaton, pp. 197–213). New York: Routledge. Lévi-Strauss C. 1974. Tristes Tropiques. New York: Atheneum. Lyng S. 1990. “Edgework: A social psychological analysis of voluntary risk taking.” American Journal of Sociology 95:851-886. Lyng S, ed. 2005. Edgework: The Sociology of Risk-Taking. New York: Routledge. Lyng S, Snow, DA. 1986. “Vocabularies of motive and high risk behavior: The case of skydiving.” Advances in Group Processes 3:157 -179. Malinowski B. 1954. Magic, Science and Religion and Other Essays. Garden City, NY: Manhart K. 2005. “Lust for danger.” Scientific American Mind, September. Maslow AH. 1943. 1961. “Peak-experiences as acute identity-experiences.” American Journal of Psychoanalysis 21:254–260. Mitchell RG, Jr. 1983. Mountain Experience: The Psychology and Sociology of Adventure. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Noyce W. 1958. The Springs of Adventure. London: John Murray. Ogilvie B. 1973. “The stimulus addicts.” The Physician and Sportsmedicine 1:61–65. Ortner SB. 1999. Life and Death on Mt. Everest: Sherpas and Himalayan Mountaineering. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Palmer C. 2004. Death, danger, and the selling of risk in adventure sport. In Understanding lifestyle sports, ed. B Wheaton, pp. 55-69. New York: Routledge. Ridgeway R. 1979. The Boldest Dream: The Story of Twelve Who Climbed Mount Everest. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. Simmel G. 1971. “The adventurer.” In On Individuality and Social Forms: Selected Writings, ed. DN Levine, pp. 187-198. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Simon J. 2002. “Taking risks: Extreme sports and the embrace of risk in advanced liberal societies.” In Embracing Risk, ed. T Baker, J Simon, pp. 177-208. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Simon J. 2004. “Edgework and insurance in risk societies: Some notes on Victorian lawyers and mountaineers.” In Edgework, ed. S Lyng, pp. 203–226. New York: Routledge. Thompson M. 1980. “Risk.” Mountain 73:44-46. Vester HG. 1987. “Adventure as a form of leisure.” Journal of Leisure Studies 6:237-249. Vivanco LA, Gordon RJ. 2003. “Tarzan was an ecotourist.” Anthropology News 44(3):11. Vivanco LA, Gordon RJ, eds. 2006. Tarzan was an Ecotourist. . .and other Tales in the Anthropology of Adventure. New York: Berghahn. Zuckerman M. 1979. Sensation Seeking: Beyond the Optimal Level of Arousal. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Zuckerman M. 2007. Sensation Seeking and Risky Behavior. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Zweig P. 1974. The Adventurer: The Fate of Adventure in the Western World. New York: Basic Books.