aspects of bura phonology

advertisement

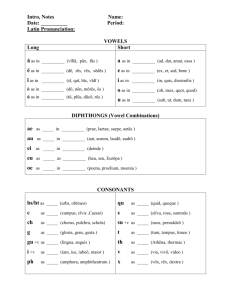

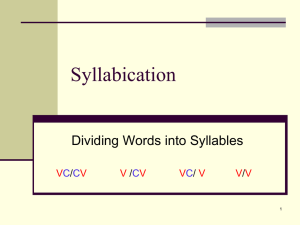

ASPECTS OF BURA PHONOLOGY OLALEKAN OLUWASEUN PAUL 07/15CB078 A RESEARCH PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS AND NIGERIAN LANGUAGES, FACULTY OF ARTS, UNIVERSITY OF ILORIN ILORIN – NIGERIA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS (B. A. HONS) IN LINGUISTICS JUNE, 2011. CERTIFICATION This essay has been read and approved as meeting the requirements of the Department of Linguistics and Nigerian Languages, University of Ilorin, Ilorin, Nigeria. _________________________________ MR. S. A. AJE Project Supervisor _________________________ DATE ______________________________ _________________________ PROF. A. S. ABDUSSALAM Head of Department _____________________________ EXTERNAL EXAMINER DATE __________________________ DATE DEDICATION This project is dedicated to Almighty God, Alpha and Omega for His love, mercy and grace over my life and for seeing me through my programme in the University of Ilorin. I also dedicate this project to my parents, Mr. and Mrs. Olalekan Abolanle, for their financial and moral support and also for their increasing prayers to ensure that I achieve the best in life. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS God’s reflection of love, care, mercy, goodness, guidance and inspiration has made this project a reality. I thank God and people that have supported me in one way or the other to make this dream an everlasting record. I am particularly in-depted to my supervisor, Mr. S. A. Aje, for his sincere concern, guidance, patience, understanding and his words of wisdom. You have deposited what money cannot buy in me. May God keep blessing you sir, (Amen). I am also immensely grateful to my dearest mother, lecturer, Mrs. Abubakre, for her deliberate support over my academic life and specially this project, despite the huddles of life she never stopped encouraging, guiding and supporting me by advising and providing necessary materials when needed. May God reward her efforts. (Amen). However, for the academic inspiration and support of the Head of Department (H.O.D), Professor Abdussalam and my wonderful lecturers in the Department of Linguistics and Nigerian Languages and that of the Faculty of Arts. I am grateful. Gratefull am to my friends and colleagues who played important roles in the course of this project. May God’s mercy always be with you all (Amen). Without God, there is no my parents, without my parents, there is no me and without me there is no this project, and for this project to come true, it has been the support of my parents Mr. and Mrs. Olalekan Abolanle for their moral, spiritual, financial, support and guidance. I am indeed very grateful. I am also grateful to my sisters and brother namely: Atinuke Omosefunmi, Olanike Utulu and Olalekan Abiodun, for their advice, focus over my activities and challenges of life, may God guide you in all of your endeavours (Amen). I wish to thank my informants, Mr. Simon Shelia and Pastor Ishaku Bitrus Nda for their unmeasurable efforts made over this project, may God fulfill your aims and objectives (Amen). Finally, I want to give thanks to the typist of this project, Mr. Sunkanmi for his full interest he had, to make sure that this project is a must of success in year 2011, I feel honoured and grateful, may God keep you His mercy (Amen). LIST OF SYMBOLS AND ABBREVIATIONS C. - a consonant V. - a vowel ~ - nasalization [] - a phonetic transcription // - a phonemic transcription - change + - morpheme boundary # - word boundary - - position of change / - environment of change H - high tone L - low tone M - mid tone [/] - high tone [\] - low tone - null or empty C1 C2 - consonant cluster TABLE OF CONTENTS Title Page i Certification ii Dedication iii Acknowledgements iv List of Symbols and Abbreviations vi Table of Contents vii List of Figures xi CHAPTER ONE: GENERAL INTRODUCTION 1.0 Introduction 1 1.1 General Background of the Language 1 1.2 Historical Background of Bura Speakers 2 1.3 Sociolinguistic Profile of Bura People 2 1.4 Genetic Classification 3 1.4.1 Genetic Classification of Bura 4 1.4.2 A Map of Bura 5 1.5 Scope and Organization of Study 6 1.6 Theoretical Framework 6 1.7 Data Collection 7 1.8 Data Analysis 8 1.9 Brief Review of the Chosen Framework 9 1.9.1 Motivation for Generative Phonology 10 1.9.2 Operational Levels of Generative Phonology 11 1.9.3 The Underlying Level 12 1.9.4 The Surface Level 12 1.9.5 Phonological Rules 13 CHAPTER TWO: BASIC PHONOLOGICAL CONCEPTS 2.0 Introduction 14 2.1 Distribution of Consonants 14 2.1.1 Bura Consonant Inventory 22 2.1.2 Distinctive Feature Classification of Bura Consonants 23 2.1.3 Justification of features 24 2.1.4 The Redundancies in Bura Consonant Sounds 27 Bura Vowel Inventory 29 2.2.1 Distribution of Vowels 30 2.2 2.2.1.1 Distribution of Nasals 31 2.2.2 Distinctive Feature Classification of Bura Vowel 33 2.2.3 The Redundancies in Bura Vowel Sounds 34 2.2.4 Tonal Inventory 35 2.2.5 Syllabic Inventory 36 CHAPTER THREE: PHONOLOGICAL PROCESSES IN BURA LANGUAGE 3.0 Introduction 38 3.1 Phonological Processes 38 3.1.1 Syllabic Structure Processes 39 3.1.1.1 Deletion/Elision 39 3.1.1.2 Insertion/Epenthesis 41 3.1.2 Euphonic Processes 43 3.1.2.1 Assimilation 44 3.1.2.1.1 Nasalization 46 CHAPTER FOUR: SYLLABLE AND TONAL PROCESSES 4.0 Introduction 48 4.1 Syllable Process 48 4.1.1 Auto Segmental Analysis 50 4.1.2 Monosyllabic Words 50 4.1.3 Disyllabic Words 52 4.1.4 Trisyllabic Words 59 Tonal Processes 62 4.2.1 Tone Pattern and Distribution 63 4.2 4.2.2 Polarization 66 4.2.3 Tone Stability 67 CHAPTER FIVE: SUMMARY, CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 5.0 Introduction 69 5.1 Summary 69 5.2 Conclusion 71 5.3 Recommendations 72 References 73 LISTS OF FIGURES 1. Map of Bura 2. Genetic Classification of Bura 3. Consonant Chart of Bura 4. Fully Specified Matrix of Bura Consonant 5. Partially Specified Matrix of Bura Consonant 6. Vowel Chart of Bura 7. Fully Specified Matrix of Bura Vowels 8. Partially Specified Matrix of Bura Vowels 9. The Structure of the Syllable CHAPTER ONE GENERAL INTRODUCTION 1.0 INTRODUCTION As an introductory chapter, we shall focus on the historical background of Bura, sociolinguistic profile of the people and the genetic classification of the language. Other sub-headings in this chapter include the scope and organization of study, theoretical framework, data collection, data analysis, and a brief review of the chosen framework. 1.1 GENETIC BACKGROUND OF THE LANGUAGE Bura is a language spoken in two adjacent states in the north-eastern part of Nigeria. Native speakers of Bura are found in the southern part of Borno and northern Part of Adamawa. In Borno state, native speakers are found, precisely, in Gwoza and Damboa districts while in Adamawa state, they live around Madagalik, Gulak, Duhu and Isge. In terms of population of speakers, the SIL website ethnologue counts 250,000 ‘Bura’ altogether (SIL, 1993). 1.2 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF BURA SPEAKERS As stated above, native speakers of Bura are found in southern part of Borno in Borno state and northern part of Adamawa in Adamawa state. In Borno state, native speakers are found, precisely, in Gwoza and Damba districts while in Adamawa state, they live around Madagalik, Gulak, Duhu and Isgel. The people of Duhu in Adamawa state migrated from Sukur mountain. Sukur mountain is located in Gombi Local Government Area in Adamawa state. The migration was due to the growth in their population and search for farm land. Quite a number of Bura speakers are literate. This is as a result of early contact with the Church of Brethen (CBM) Missionaries which brought education and medical care to Bura people. 1.3 SOCIOLINGUISTIC PROFILE OF BURA LANGUAGE The Bura people have a very rich sociolinguistic profile just like many African people. These include their system of government with the king as the head. The king is assisted by leaders of different units like farming and army, known as ‘Lawans’. Christianity, Islam and African Traditional Religion (ATR) are the religions practiced by Bura people. A rough estimate of the religious percentages is as follows: Muslim 78%, Christians 20%, Traditionalists 2%. Traditionally, Bura people wear the normal Hausa attaire and carry sticks (especially those on mountain). The women are seen with skirts and wrapper which they tie on one side above the shoulder. Their hair is always cut short and covered with a calabash. The economic system of Bura agriculture. In fact, agriculture is the dominant occupation of the Bura. Among their festivals are ‘maize harvest’ festival which performed before fresh corn can be eaten and ‘mbal’ festival for both men and women who are suitable for marriage. 1.4 GENETIC CLASSIFICATION Bura, Comrie (1987: 706) and Newman (1977) quoted in Meritt (1991: 92), is classified under Bura group of Biu-Mandara branch of Chadic sub-family of the Afro-Asiatic Phylum. This is shown by the family tree below. AFRICA Niger-Kodorfania Afro-Asiatic Nilo-Saharan Egyptian Cushitic Semitic West Chadic Tera Kotoko Group Group Biu Mandara Omotic Khoisan Berber East Chadic Bura Higi Mandara Group Group Group Chadic Masa Matakam Sukur Daba Bata Group Group Group Group Kilba Chibak Bura(Pabir) 1.4.1 GENETIC CLASSIFICATION OF BURA Margi Puta 1.4.2 A MAP OF BURA 1.5 SCOPE AND ORGANIZATION This long essay is divided into five chapters. The first chapter is the introductory chapter which will contain the general introduction of the research, the historical background of the speakers, sociolinguistic profile of Bura people, genetic classification of the language, collection and analysis of the data and the theoretical framework employed. Chapter two deals with basic phonological concepts such as the sound inventory, tonal inventory, syllable inventory and sound distribution. The chapter ends with a distinctive feature classification of distinctive sounds of the language. Finally, chapter five summarizes and concludes the work. 1.6 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK This project is theoretically modelled according to ‘generative’ grammar, a theory propounded by Chomsky in the 1950s. A generative grammar consists of a set of formal statements which delimit all and only all possible structures that are part of the language in question. The basic aim of a generative of linguistics to present in a formal way the tacit knowledge native speakers have of their language. 1.7 DATA COLLECTION The data used for this project was collected from native speakers of the language. The data was collected through the use of the Ibadan word of 400 basic items. Below are pieces of information about the informants. 1. NAME: Simon Shelia SEX: Male AGE: 39 OCCUPATION: Lecturing NUMBER OF YEARS SPENT IN BURA: 26 years OTHER LANGUAGES SPOKEN: English, Hausa, Chibok 2. NAME: Ishaku Bitrus Ndah SEX: Male AGE: 37 OCCUPATION: An Evangelist NUMBER OF YEARS SPENT IN BURA: Occasionally during holidays OTHER LANGUAGES SPOKEN: English, Hausa, Fufulde 1.8 DATA ANALYSIS On collection of the data, the researcher listens to the recorded tape and writes the words in a chosen orthography and transcribes the words phonetically. By doing this, the researcher was able to observe the behaviour of segments in the language. The principle of minimal pair (a principle of identifying contrastive sounds) was used as a technique for identifying contrastive segments. Through this, the researcher accounts for the sound inventory and the syllable inventory of the language. The minimal pair principle was also used in accounting for the tonal inventory of the language. Words that are homographic but differ in pitch (tone) are treated as distinct words. Such contrast is analyzed as the language attesting distinct tonemes, hence, the language being tonal. Sounds are also examined in terms of their distribution. That is, the structural positions in which a sound can occur or occurs and the class of sounds that can pattern together in a given structural position. This triggers an ‘if-then’ condition that warrants the use of distinctive features and the postulation of phonological rules and rule formalization. 1.9 BRIEF REVIEW OF THE CHOSEN FRAMEWORK This project is theoretically built on the mode of Generative Grammar (G.G). The generative approach of language puts greater emphasis on the need for a linguistic analysis to have explanatory power, that is, to explain adequately what the native speaker intuitively ‘knows’ about his language (Hawkins, 1984: 22). Generative grammar’s meaning is something like ‘the complete description of a language’, that is, what the sounds are and how they combine, what the meaning of the words are, etc. (Davenport and Hannahs, 2005: 4). Generative Phonology is particularly associated with the works of the American linguist, Noam Chomsky and his followers. The joint work on phonology by Chomsky and Halle published in 1968 as ‘sound patterns of English’ (SPE) marked the emergence of generative phonology as a new theory and framework of description. Generative Phonology is an alternative to ‘taxonomic’ or ‘classical’ phonemics, and on the other an ambitious attempt to build a description of ‘English’ phonology on a transformational-generative theory of language (Clark Yallop and Fltehcer, 2007: 129). Chomsky criticizes the taxonomic phonologists concerned with segmentation, contrast, distribution and biuniqueness and puts forward the view that phonological description is not based on analytic procedures of segmentation and classification but rather a matter of constructing the set of rules that constitute the phonological component of a grammar (P. 129). 1.9.1 MOTIVATION FOR GENERATIVE PHONOLOGY Generative Phonology is a theory which built on the insights of taxonomic phonemes even while remodelling the focus of phonological analysis (Oyebade, 2008: 9). It seeks to resolve many issues that the former theory (Taxonomic Phonemics) left unaddressed. These include: Linguistic intuition, Foreign Accents, Speech errors and Language aquisition. Talking about ‘Linguistic Intuition’, the question that Generative Phonology attempt to answer is ‘how do we know that native speakers know the sequential constraints of their own language (Hyman, 1957: 19)’? Chomsky and Halle (1968: 38) affirm that knowledge of the sequential constraints is responsible for the fact that speakers of a language have a sense of what sounds like a native word and what does not. In other words, speakers usually subject the sounds of foreign languages they intend pronouncing to the phonological pattern of their own language. A third motivation for GP is ‘speech errors’. Oyebade (2008: 11) reports that a large number of utterances heard by man are defective, possibly as a result of slips of the tongue, stress, stage fright, paralinguistic factors, psychological, as well as physiological factors. The final motivation of GP is ‘language acquisition’. The errors children usually make when they are attempting to discover the phonology of their own language during the stage of language acquisition is quite revealing. 1.9.2 OPERATIONAL LEVELS OF GENERATIVE PHONOLOGY There are two operational levels/representations of generative phonology: the underlying level/representation and the surface level/representation. Between these two extremes is an intermediary that mediates or the underlying level to generate surface representations. The mediators are phonological rules (Oyebade, 2008: 15). 1.9.3 THE UNDERLYING LEVEL The underlying level/representation is also called the phonemic or phonological level/representation. The underlying representation represents the native speaker’s tacit knowledge (Chomsky and Halle 1968: 14) specifically propose that phonological representation are mentally constructed by the speaker and the hearer and underlie their actual performance in spelling and “understanding”. The underlying representation are relatively abstract and do not manifest surface variants. 1.9.4 THE SURFACE LEVEL The surface representation, on the other hand, is the physical instatiation of underlying forms (Davenport and Hannahs, 2005: 122). The surface representation can be likened to performance – the actual use of language. It is also called the phonetic level because it deals with the physical manipulation of the organ speech to produce linguistic forms. It is accompanied with a lot of nuances that do not characterize the native speaker’s competence, hence, its predictableness. They are complete with lexical items and reflect the grammatical rules of the language. 1.9.5 PHONOLOGICAL RULES Since the underlying/phonemic level differs from the surface level, phonological rules serve as mediators between these two extremes. Phonological rules link them together. Phonological rules are facts that are expressed in formal statements which act on the information stored in the human’s (native speaker’s) instinct. Phonological rules that act on underlying forms of the language to yield surface phonetic forms. CHAPTER TWO BASIC PHONOLOGICAL CONCEPTS 2.0 INTRODUCTION This chapter examines key concepts in phonology. To be also considered in this chapter are the sound, tones, and syllable inventory of the language. A distinctive feature classification of the distribution sounds of language as well as knowledge of the distribution of sounds in language is also included in this chapter. 2.1 DISTRIBUTION OF CONSONANTS /p/ Voiceless Bilabial Plosive pífù ‘heart’ sírípí ‘mat’ mכsùp ‘spear’ /b/ Voiced Bilabial Plosive batahu ‘arm’ àjàbà ‘plantain’ àjàbà ‘plantain’ /k/ Voiceless Velar Plosive kútá ‘belly’ fùkũ ‘chin’ mũsúmakì ‘hunter’ /g/ Voiced Velar Plosive gàrí ‘mountain’ dĩgìa ‘knife’ dĩgìa ‘knife’ /t/ Voiceless Alveolar Plosive tílì ‘saliva’ kútá ‘belly’ kútá ‘belly’ /d/ Voiced Alveolar Plosive dìr ‘town’ dзãdà ‘tongue’ dзãdà ‘tongue’ /l/ Voiced Alveolar Liquid lìà ‘iron’ álí ‘leaf’ sìl ‘leg’ /r/ Voiced Alveolar Liquid ráká ‘small’ dárè ‘taste’ dárè ‘taste’ /f/ Voiceless Labio-Dental Fricative fùkũ ‘chin’ pífù ‘heart’ pífù ‘heart’ /v/ Voiced Labio-Dental Fricative vìrì ‘day’ ivìrì ‘fear’ ivìrì ‘fear’ /h/ Voiced Glottal Fricative hir ‘teeth’ ùhà ‘breast’ ùhà ‘breast’ /kw/ Voiceless Labialized Alveolar Plosive kwárá ‘donkey’ skwár ‘soup’ skwár ‘soup’ /gw/ Voiced Labialized Alveolar Plosive gwòrò ‘kolanut’ kugwà ‘calabash’ kugwà ‘calabash’ /bw/ Voiced Bilabial Plosive bwa ‘push’ mbwà ‘groom’ nábuà ‘door’ /fw/ Voiced Labio-Dental Affricate tónfùà ‘leopard’ tónfùà ‘leopard’ tónfùà ‘leopard’ /kp/ Voiceless Labio-Velar Plosive kpá ‘beat’ kpá ‘beat’ kpá ‘beat’ /gb/ Voiced Labio-Velar Plosive gègégbó ‘heavy’ bógbá ‘strong’ bógbá ‘strong’ /m/ Voiced Bilabial Nasal mamì ‘blood’ lmu ‘orange’ sכm ‘ear’ /n/ Voiced Alveolar Nasal ninim ‘sweet’ hóná ‘salt’ hóná ‘salt’ /ŋ/ Voiced Velar Nasal ŋgilà ‘refuse’ ŋgilà ‘refuse’ ŋgilà ‘refuse’ /ת/ Voiced Palatal Velar תárá ‘lick’ תárá ‘lick’ תárá ‘lick’ /m/ Voiced Bilabial Fricative mfà ‘tree’ mfà ‘tree’ mfà ‘tree’ /j/ Voiced Palatal jímí ‘water’ dכjá ‘cassava’ dכja ‘cassava’ /w/ Voiced Labio-Velar wàdá ‘groundnut’ ùwùlàím ‘charcoal’ ùwùlàím ‘charcoal’ // Voiceless Palato-Alveolar Fricative ámbárí ‘wind’ íí ‘hair’ íí ‘hair’ /з/ Voiced Palato-Alevolar Fricative mãзà ‘red’ mãзà ‘red’ mãзà ‘red’ /t/ Voiceless Palato-Alveolar Affricate tívì ‘feaces’ tívì ‘feaces’ tívì ‘feaces’ /dз/ Voiced Palato-Alevolar Affricate dзãdà ‘tongue’ mãdзa ‘oil palm’ mãdзa ‘oil palm’ 2.1.1 BURA CONSONANT INVENTORY Consonants are sounds made by exploiting the articulatory capabilities of the tongue, teeth and lips in such a way that airflow through the mouth cavity is radically constricted or even temporarily blocked (Clark, Yallop and Fletcher, 2007: 13). Bura attests the following consonants: pb, td , kg, lr, mnŋm, hfv, sz, kp gb, kw gw, jw, bw, fw, ʒ, t, dз. The above consonants are represented in a chart thus: Labialized plosive Fricative bw f Labialized fricative Affricate Nasal v d s z ʒ t dʒ Kp gb m Lateral Flap Approximant Bura Consonant Chart n gw h fw m Kw Glottal kg Labialize d velar Palatal Palatoalveolar Aveolar t Labiovelar p b Velar Plosive Labio dental Bilabial PLACE OF ARTICULATION n ŋ j w l r p b t d k g kw gw bw fw kp gb ʒ dʒ t m n ŋ n m h j w s z l r f v + CONS + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + SON - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - + + + + + - - - - - - - - - + CONT - - - - - - - - - + - - + - - - - - - - - - - + + + + + + + + NAS - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - + + + + + - - - - - - - - - + DEREL - - - - - - - - - - - - - - + + - - - - - - - - - - - - - - + LAT - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - + - - - + VOICE - + - + - + - + + - - + - + - - + + + + + + + + - + + + - + + STRID - - - - - - - - - - - - - - + + - - - - - - - - - - - - - - + COR - - + + - - - - + + - - + + + + - + - - - - - - + + + + + + + ANT + + + + - - - - - - - - - - - - + + - - - - - - + + + + + + + LAB + + - - - - + + - - - - - - - - + - - - - - - - - - - - + + Fully Specified Matrix 2.1.2 DISTINCTIVE FEATURE CLASSIFICATION OF BURA CONSONANT p b t d k g kw gw bw fw kp gb з - - - - - - - - - + - - + - - - - - - - - - - - dз t m n ŋ n m h j w s z - - - + + + - - - l r f v + + + + CONS + SON + CONT + NAS + DEREL + LAT - - - - - + VOICE - + - + - + - + + - - + - + + - + + + - + + - + + STRID - - - - - - - - - - - - - - + + - - - - - - - - + COR - - + + - - - - + + - - + + - + + + + + + + ANT + + + + - - - - - - - - - - + + - - - - - - + + + + + + LAB + + - - - - + + - - - - - - + - - - - - - - - - - + + Partial Specified Matrix - - - + - - 2.1.3 JUSTIFICATION OF FEATURES According to Oyebade (2008: 29-33), the foregoing features are defined as follows: 1. Syllabic [+ Syll]: they are sounds that constitute syllabic peaks (vowels, syllabic consonants versus glides, non syllabic consonants). 2. High [+ High]: High sounds are produced by raising the tongue body toward the palate (high vowels versus low vowels). 3. Low [+ Low]: Low sounds are produced by drawing the body of the tongue down away from the roof of the mouth (Low vowels versus high vowels). 4. Back [+ Back]: Back sounds are produced with the tongue body relatively retracted (back vowels versus front vowels). 5. Round [+ Round]: Round sounds are produced with protrusion of the lips (rounded vowels versus front vowel). 6. Advanced Tongue Root [+ ATR]: They are sounds produced by drawing the root of the tongue forward [i, e, o, u, vs , כ, a]. 7. Tense [+ Tense]: They are produced with a tongue body involving a greater of constriction than that found in their lax counterpart (tense versus lax vowels). According to Oyebade (2008: 29-33), the above distinctive features are justified as follows: 1. Consonant [+ Cons]: They are sounds produced with a sustained vocal tract constriction (obstruents, nasals, liquids versus vowels and glides). 2. Sonorant [+ Son]: Sonorants are produced with a vocal tract configuration suffcieitnly open that the air pressure inside and outside the mouth is approximately equal (vowels, glides, liquids nasals versus stops, and fricatives). 3. Continuants [+ Cont]: They are sounds formed with a vocal tract configuration allowing the aristream to flow through the midsaggital region of the oral tract (vowels, glides, fricatives versus nasal, oral stops). 4. Nasals [+ nas]: nasals are pr oduced by lowering the velum so that the air passes through the nasal cavity (nasals versus other sounds). xxxvii 5. Delayed Release [+ derel]: They are sound produced by totally constricting the airstream at specific points in the oral tract and releasing it gradually [affricates versus other sounds). 6. Lateral [+ lat]: Laterals are produced with the tongue placed in such a way as to prevent the airstream from flowing outward through the centre of the mouth (lateral, sonorant versus all others). 7. Voice [+ Voice]: Voiced sounds are produced with periodic vibration of the vocal cords; voiceless sounds lack such periodic vibration (voiced versus voiceless consonants). 8. Strident [+ Strid]: Strident sounds are produced with a complex constriction forcing the airstream to strike two surfaces, producing fricative noise (sibilants, labiodentals versus all others). 9. Coronal [+ Cor]: Coronals are produced by raising the tongue blade towards the teeth or the hard palate (dentals, alveolars, palatoalveolars, palatals versus labials, velars). 10. Anterior [+ ant]: Anterior sounds are produced with a primary constriction at or in front of the alveolar ridge (labials, dentals, alveolars, versus palato-alveolars, palatals, velars). xxxviii 11. Labial [+ lab]: Labials are formed with constriction at the lips (labial consonants versus all others). 2.1.4 THE REDUNDANCIES IN BURA CONSONANT SOUNDS 1. if: [+ son] then [-derel] 2. if: [+ cont] Then: [-nas] 3. If: [+ strid] Then: [- lat] 4. If: [+ son] Then: [- strid] xxxix 5. If: [+ nas] Then: [+ voice] 6. If: [+ derel] Then: [- son] 7. If: [+ nas] Then: [- cont] 8. If: [+ cont] Then: [- derel] 9. If: [+ nas] Then: [- lat] 10. If: [+ derel] Then: [- son] xl xli 2.2 Bura Vowel Inventory Bura Oral Vowels Front High Central Back i Mid-high u e Mid-low o ε Low a Bura Nasal Vowels Front High Back ĩ Mid-high Mid-low low Central Ũ ẽ õ כ ε ã 2.2.1 Distribution of Vowels xlii /i/ High front Unrounded Vowel ivìrì ‘fear’ ninim ‘sweet’ ímí ‘bad’ /u/ High Back Rounded Vowel ùhà ‘breast’ wulia ‘neck’ pífù ‘heart’ /e/ Mid-High Front Unrounded Vowel èù ‘bone’ délépá makè /o/ ‘dawn’ ‘three’ Mid-High Back Rounded Vowel ómdá ‘nine’ pósó ‘darkness’ sófó ‘bat’ xliii // Mid-Low Front Unrounded Vowel lmu ‘orange’ jbí ‘rope’ jímírìh ‘rain’ // Mid-Low back Rounded Vowel mpù ‘white’ djá ‘cassava’ djá ‘cassava’ /a/ Low-Back Unrounded Vowel álí ‘leaf’ lálè ‘bow’ kusa ‘grass’ 2.2.1.1 Distribution of Nasals /ĩ/ High Front Nasal Unrounded Vowel sĩbùrù ‘navel’ nsĩsé ‘sit’ jrĩ ‘millet’ xliv /ũ/ High Back nasal Rounded Vowel mũsí ‘dwell’ sũnì ‘dream’ sũnì ‘dream’ /ẽ/ Mid-High Front Nasal Unrounded Vowel ŋgẽlèm ‘crocodile’ ŋgẽlèm ‘crocodile’ kialẽ ‘child’ /õ/ Mid-High Back Nasal Rounded Vowel õdòkúmádi ‘ninety’ àrúõfùà ‘four hundred’ tehõtà ‘delegate’ // Mid Low Front Nasal Unrounded Vowel dʒlì ‘play’ bjì ‘friend’ bjì ‘friend’ // Mid-Low Back Nasal Rounded Vowel gb ‘thigh’ xlv gb ‘thigh’ gb ‘thigh’ /ã/ Low Back Nasal Unrounded Vowel àtó ‘was’ dɔãdà ‘tongue’ dɔãdà ‘tongue’ 2.2.2 Distinctive Feature Classification of Bura Vowel Fully Specified Matrix + + + + + + I Syll + High + Low Back ATR + Tense + e + + + - + + - a + + + + + + + - o + + + + - u + + + + + a o u - + + Partial Specified Matrix I + + + + + Syll High Low Back ATR e xlvi + Tense + - - + - 2.2.3 The Redundancies in Bura Vowel Sounds 1. If: [- syll] Then: [- low] 2. If: [-back] Then: [- low] 3. If: [+ high] Then: [+ ATR] 4. If: [+ round] Then: [+ back] 5. If: [-ATR] Then: [- round] 6. If: [- back] xlvii - + Then: [- round] 2.2.4 TONAL INVENTORY Bura attests three register tones: high [/], mid (unmarked) and low [\]. The data below attest to thus: High Tone: úvúm ‘cotton’ jímí ‘water’ íí ‘hair’ kútá ‘belly’ púl ‘nail’ Mid Tone hil ‘guinea corn’ kusa ‘grass’ lεmu ‘orange’ wulia ‘neck’ ksuku ‘market’ Low Tone xlviii dì ‘ground’ vìrì ‘day’ ùhà ‘breast’ fàkù ‘dry season’ hà ‘song’ 2.2.5 SYLLABIC INVENTORY Bura has three basic syllable structures: (1) CVC (2) CCV (3) CV xlix CVC hil ‘guinea corn’ sm ‘ear’ hir ‘teeth’ sìl ‘leg’ màl ‘oil’ CCV ndá ‘person’ púá ‘pour’ nbà ‘burn’ CV sà ‘beat’ sí ‘hand’ jí ‘body’ dì ‘ground’ tà ‘die’ l CHAPTER THREE PHONOLOGICAL PROCESSES IN BURA LANGUAGE 3.0 INTRODUCTION In this chapter, we shall examine the phonological processes of Bura. The following processes, which the language attests shall be discussed: deletion, insertion, assimilation and nasalization. 3.1 PHONOLOGICAL PROCESSES Phonological processes are results of pronunciation in connected speech. In connected speech, certain segments have the tendency to run together; extra segments may be added to ensure smoothness of speech some segments adopt a less clearly defined phonetic form; and some completely disappear. Phonological processes are therefore, sound modifications motivated by the need to maintain euphony in a language or to rectify violations of well-formedness constrains in the production of an utterance (Oyebade, 2008: 61). Oyebade classifies phonological processes into two: syllable structure processes and euphonic processes. li 3.1.1 SYLLABLE STRUCTURE PROCESSES IN BURA LANGUAGE According to Oyebade (2008: 62), syllable structure processes are phonological processes which involve the modification of a derived syllable structure to conform with a language preferred syllable structure through the manipulation of distribution of vowels and consonants in a word. Deletion, coalescence and epenthesis are examples of phonological processes classified under syllable structure processes. With respect to Bura, however the following are attested: deletion/elision and insertion/epenthesis. 3.1.1.1 DELETION/ELISION It is a phonological process common in languages. It involves the loss of a segment under some language-specifically imposed conditions. Deletion involving vowels is called elision. Vowels are usually elided when two or more vowels occur across morpheme boundary in which case the first or the second of the contiguous vowels may be dropped. Bura attests both consonant deletion and vowel elision. The data below illustrate this phenomenon. 1. /kúgùnà/ + money 2. /súsúm/ /nbùà/ house + /ndásì/ [kúgùnàbùà] ‘house rent’ lii [súsumdási] 3. 4. food swallow ‘swallow food’ /malukum/ + /kìlfà/ [malukumìlfà] fat fish ‘big fish’ /dákù/ + good house /nbùà/ [dakùbùà] ‘beautiful house’ Prose Statement: A consonant get deleted when two consonants followed each other at the morpheme boundary. Formal Statement: C /+ ______ Vowel Elision: 1. /tímbá/ + /àdè/ [tmbádè] pepper 2. 3. 4. grind ‘grind pepper’ /ímí/ + /ivìrì/ [ímívìrì] bad fear ‘bad fear’ /pálá/ + /ivìrì/ [pálávìrì] big fear ‘heavy fear’ /sóltà/ + /àyàbà/ liii [sóltàyàbà] fry 5. banana /hólhólá/ + dry /èshù/ ‘friend plantain’ bone [hólhóláshù] ‘dry bones’ The above data show explicitly that the second of two contiguous vowels is elided in Bura. This process can be captured using the rule format thus: V [+ Syll] /V + ______________ [Syll] This rule says that a vowel is deleted if it occurs after a similar vowel across word boundary. 3.1.1.2 Insertion/Epenthesis Insertion or epenthesis involves the introduction of an extraneous segment into an utterance in order to break up unwanted or unallowed sequences. Although consonant insertion is rare in language, vowel insertion is not an uncommon occurrence. Insertion is not limited breaking up clusters; it is also manifested at the end of words to ensure that a closed syllable does not end a word. It could also introduce an extraneous vowel at the beginning of a word-prothesis as exemplifies in Spanish. However, Bura does not attest prothesis, rather it allows liv certain consonants to end a word. Examples of vowel insertion to break up unwanted sequence can be shown by the following: /CP/ [kpu] ‘cup’ /ta’ma:tau/ [tamatiru] ‘tomato’ /’teibl/ [tebu] ‘table’ /’mauta/ [‘moto] ‘motor’ Epenthesis is a very common phenomenon in the loan-word phonology of many African languages. The Hausa words borrowed into Bura. For example, are shown in the following: Hausa Bura makaranta ‘school’ makaranta ‘school’ lemú ‘orange’ lemú ‘orange’ àyàbà ‘banana’ àyàbà ‘banana’ Bura also borrowed from Yoruba language as seen in: Yoruba Bura bàbá ‘father’ bàbá ‘father’ màmá ‘mother’ màmá ‘mother’ àdá ‘cutlass’ àdá ‘cutlass’ lv Although, Bura permits consonant cluster involving a nasal sound and any other sound or approximants and (e.g. [nja] ‘mouth,’ [mbál] ‘palm wine’ [mfà] ‘tree’, [ndʒerìl] ‘mortar’, [npa] ‘war’ [ŋgẽlèm] ‘crocodile’, etc.). It is observed that Bura allows certain consonants ([m, n, p, l, r] to end a word. Where there are no such sounds at the end of a word, a vowel ends. However, we also observed that there are sequence of non-nasal consonant which are attested in Bura language. The following, are the examples given below: [sáptá] ‘gather’ [hàlhàlà] ‘old’ [hólhólá] ‘dry’ 3.1.2 EUPHONIC PROCESSES In section 3.1.1.1 above, we examined syllable structure processes as the first category of phonological processes. In this section, we shall discuss the second category-euphonic processes. Oyebade (2008) says phonological processes classified under this category ‘make pronunciation easier or pleasing to the ear’. Among these processes are assimilation and vowel harmony. Since lvi Bura, a Chadic language, does not attest vowel harmony, we shall limit our discussion to assimilation. 3.1.2.1 ASSIMILATION Assimilation occurs in an environment where two contiguous sounds with different modes of production become identical in some or all of the features of their production. It is the modification of a sound in order to make it more similar to some other sound in its neighbourhood (Katamba, 1989: 80). Katamba reports that assimilation is advantageous because it results in smoother, more effortless, more economical transitions from one sound to another. He went further to say that assimilation facilitates the task of speaking; and that native speakers generally usually try to conserve energy by using no more effort than necessary to produce an utterance. In terms of directionality, assimilation could be anticipatory/regressive or preservative/progressive. (Katamba, 1989: 84 and Oyebade, 2008: 62). It is anticipatory or regressive if a sound changes to become more like the sound that follows it. Conversely, it is preservative or progressive if a sound becomes more like the sound that precedes it. The Bura data below show cases of assimilation. lvii DATA A: /ngèlà/ [ŋgèlà] ‘abuse’ /nkà/ [ŋkà] ‘return’ /ngilà/ [ŋgilà] ‘refuse’ /ngegírítà/ [ŋgegírítà] ‘pull’ The data above describe a case of regressive or anticipatory assimilation in Bura. as clearly shown in the data, the underlying alveolar nasal /n/, in anticipation of the velar sounds, changes to a velar nasal [ŋ]. This can formally expressed thus: lviii + nasal + ant + cor + nas + ant - cor +obst - cont - ant - cor The above rule can be interpreted as saying an alveolar nasal changes to a velar nasal before a following velar sound. DATA B: /nbál/ [mbál] ‘palm wine’ /chínbá/ [tímbá] ‘pepper’ Just like data A, data B also show a case of anticipatory assimilation in Bura. In B, however, the alveolar nasal /n/ changes to a bilabial nasal [m]. This change can be represented in formal notations as: + nasal + cor - cor - ant - cor +nas + ant - cor + ant The above rule says an alveolar nasal becomes a bilabial nasal before a bilabial sound. 3.1.2.1.1 Nasalization lix Nasalization is an assimilatory process attested in Bura. It is a process whereby an oral segment acquires nasality from a neighbouring segment. Such neighbouring segment is traditionally a nasal consonant. In terms of directionality, just like the case of assimilation discussed above, nasalization in this language is regressive or anticipatory. The following are some examples: /pínjù/ [pĩdʒù] ‘mosquito’ /nsìsé/ [nsĩsé] ‘sit’ /sùnnì/ [sũnì] ‘dream’ /síndà/ [sĩdà] ‘know’ /dántà/ [data] ‘remember’ /antó/ [ãtó] ‘was’ In this language, a vowel is nasalized if it is followed by a nasal sound. This can be stated formally as follows: V [nas] + ant + cor + nasal lx CHAPTER FOUR SYLLABLE AND TONAL PROCESSES 4.0 Introduction In chapter two, an inventory of the tones and the syllable structure of Bura was carried out. This chapter will examine and account for the principles involved in the arrangement of phonemes to form a syllable and to establish processes that underlie the modification of tones before they reach their actual phonetic forms. According to Goldsmith (1995: 207), the syllable can be viewed as the structural units providing melodic organization to such strings. This melodic organization is based, for the most part on the inherent sonority of phonological segments, that is, the loudness of a sound relative to other sounds produced with the same input energy. The Goldsmith autosegmental approach to syllable analysis will be adopted in the study of the syllable structure of Bura. 4.1 Syllable Process Phonological research has given us a wealth of insight into shared properties in the phonology of human language. These shared properties and universal preferences of language have formed a family together in view of the lxi relatedness of their functions. Among these shared properties of language is syllable structure constraints. Simply put, the syllable is the phonological unit which organizes segmental melodies in terms of sonority (Goldsmith, 1995: 207). Furthermore, Clark, Yallop and Fletcher (2007: 67), defined a syllable as a combination of sounds which consists of a vocalic peak, which may be accompanied by a consonantal onset or coda. In other words, syllable has a family of constraints that is born out of the syllable structure preference of natural language. Some of these constraints are, onset, peak or nucleus and coda. Onset is the beginning of a syllable, peak is the central and coda is the end of a syllable. However, the internal structure of syllable can be diagrammatically represented thus: Syllable Onset Rhyme Nucleus Coda (Centre, peak) lxii (Yule 1996: 58) Therefore, the analysis of syllable process in Bura language will be carried out or discussed under the prominent theory of phonology called autosegmental phonology. 4.1.1 Autosegmental Analysis 4.1.2 Monosyllabic Words They are words with only one syllable. Monosyllabic words, in Bura, have the following syllabic process: CV, CVC, CCV, VCV and CCVC. Below are some examples: CV kí ‘head’ jù ‘body’ sí ‘hand’ tá ‘cooking’ hà ‘sing’ CVC s ɔ m C V C ‘some’ lxiii d ì r C V C h I r C V C d ì l C V C ‘town’ ‘teeth’ ‘leg’ It should be noted that in a C1C2V structure, C1 is a Nasal sound C1C2V n j à C1 C2 V ‘mouth’ lxiv m f à C1 C2 V m à l C V C ‘tree’ ‘oil’ C1C2VC m b á l C1 C2 V C ‘palmwine’ In Bura, only nasals and liquids are allowed to end a word, otherwise, a vowel ends. 4.1.3 Disyllabic Words They are words with two syllables. They have the following syllable processes: CVCV, CCVCV, CCVCVC and CVCVC. Some examples are given below: CVCV lxv í í C V C V á t ú C V C V k ú m í C V C V ù h à ‘breast’ V C V ‘hair’ ‘stand’ ‘jaw’ VCV lxvi ù V C V á l í V C V ú h ù V C V a d á V C V kp é f ù ‘bone’ ‘leaf’ ‘fire’ ‘matchet’ CVCV ‘heart’ lxvii C V C V k ú t á C V C V ‘belly’ C1C2VCV m b a l ù C1 C2 V C V n m ù j ì C1 C2 V C V m m a l à C1 C2 V C V ‘wine’ ‘buffalo’ ‘male’ lxviii n d á s i C1 C2 V C V ‘swallow’ C1C2VCVC n d é s a l C1 C2 V C V C n dʒ é r ì l C C V C V C ‘wall’ ‘man’ ‘mortar’ CVCVV dɔ ã b ú à C V C V V k á l á ù ‘sand’ lxix C V C V V s à p ú à C V C V V ‘spin’ CVCVC kp í l ú m C V C V C p ì n á m C V C V C f ĩ dɔ ù m C V C V C ‘yam’ ‘maize’ ‘ashes’ lxx g ì l à m C V C V C m s ù p C V C V C ‘water pot’ ‘spear’ 4.1.4 TRISYLLABIC WORDS They are words with three syllables. The syllable processes for trisyllabic words is as follows: CVCVCV p ú t i v ì C V C V C V b á t á h ú C V C V C V ‘buttocks’ ‘arm’ lxxi k à dɔ í r ì C V C V C V t é f í r à C V C V C V s í r í p í C V C V C V ‘vagina’ ‘thorn’ ‘mat’ CCVCVCV n s e z ũ t à C C V C V C V n d e k ó w á lxxii ‘throw’ ‘split’ C C V C V C V CVCVCVCV í í k ú m í C V C V C V C V b ù r ù k ù t ù C V C V C V C V j í m í r ì h C V C V C V C V t é r í m à m à lxxiii ‘beard’ ‘wine’ ‘rain’ ‘bee’ C V C V C V C V s à r ì b ú l à C V C V C V C V ‘banana’ VCVCV à j à b à V C V C V i w í V C V C V a r ú p á V C V C V ‘cat’ ‘hundred’ lxxiv ‘wring’ 4.2 TONAL PROCESSES Just as segments could be modified or influenced when they collocate or when morphemes are combined together in order to ease articulation, so also tone, as a suprasegmental (or prosodic) feature, can be modified. In tonal language the mechanism that makes this possible is usually referred to as tonal processes. Tonal processes, according to Schuh (1978: 21) deal with influence of tone on each other or the interaction and the relationship between tone and segments. Also, they refer to influence of or change in pitch that is traceable to neighbouring tonal or segmental environment or some special morphological marking. Before going into tonal process employed in Bura, a quick survey of the distribution and pattern of tones in the language is appropriate. 4.2.1 TONE PATTERN AND DISTRIBUTION lxxv As mentioned earlier, Bura has three contrastive register tones namely, High, Mid and Low. These tones pattern that: i. High-High [íí] ‘hair’ [kútá] ‘belly’ [kúmí] ‘jaw’ [sũsũ] ‘food’ [jímí] ii. ‘water’ High-Mid [mãdʒa] ‘oil palm’ [mábu] [data] iii. ‘mud’ ‘remember’ High-Low [kútèr] ‘nose’ [kpéfù] ‘heart’ [tílì] [kpúsà] [báʒì] ‘saliva’ ‘snow’ ‘friend’ lxxvi iv. Low-Low [fùkũ] ‘chin’ [gìlàm] ‘water pot’ [vìrì] ‘night’ [vìjà] ‘rain season’ [fàkù] ‘dry season’ v. Low-High [bí] ‘cloth’ [fùgúm] ‘cock’ [bàbá] [màmá] ‘father’ ‘mother’ [gèká] vi. ‘call’ Low-Mid [hàze] ‘grind’ [bilem] ‘new’ vii. Low-High-Low [sùsúrì] [ùkásì] ‘kneel’ ‘turn around’ lxxvii [sàpúà] ‘spin’ [dʒbũtà] ‘break’ [ndʒérìl] ‘mortar’ viii. Mid-Mid [dɔãdɔar] ‘tongue’ [lmu] ‘orange’ [laku] ‘road’ [kefi] ‘work’ [towa] ix. ‘weep’ Mid-Low [mamì] ‘blood’ [ù] ‘bone’ [kugwà] ‘calabash’ [namzà] ‘red’ The above tonal patterns/distribution show that most words containing one morpheme in this language have the following tone melodies: H,L,M,H,HM,LM,ML, and LHL in respect of the number of syllables they contain. lxxviii 4.2.2 POLARIZATION Polarization occurs when a morpheme is assigned a tone which is opposite to that of its neighbouring morpheme. When an underlying morpheme posited to be unmarked or mid tone is assigned, a tone which is opposite to that of a neighbouring morpheme (from which it gets its tone), polarization can be said to have taken place (cf. Kenswicz, 1994: 313). In Bura counting system, the formation of some tense numbers (such as fifty, thirty and eighty) require a combination of a morpheme denoting a unit number (five, three and eight), and the morpheme denoting the number ‘ten’ ([kúmádi]). The process, however, triggers tone polarization. The following are some examples of tone polarization in Bura. /tofu + kúmádi/ five ten /tisu + kúmádi/ eight ten /makiri + three ten [tòfùkúmádi] ‘fifty’ [tìsùkúmádi] ‘eighty’ kúmádi/ [màkìrìkúmádi] ‘thirty’ lxxix The data given above show that the morphemes for the ‘unit’ numbers in Bura language counting system which are unmarked at the underlying level, become the pillar opposite of the morpheme for ‘ten’ at the surface representation. It can be observed also that the high tone of the morpheme for ‘ten’ that is contiguous with the unmarked-mid tone morphemes of the ‘unit’ numbers (at the unmarked underlying level) trigger the polarization which manifests at the surface level. 4.2.3 TONE STABILITY In many languages when an underlying tone-bearing segment (normally a vowel) is either deleted or becomes nonsyllabic and loses its ability to bear tone, the tone still survives and surfaced on an adjacent syllable. Bura (cf. Hoffman, 1963; Katamba, 1989: 194 and Oyebade, 2008: 146) has the following examples: /ùhù/ + /ímí/ [ùhúmí] fire bad ‘bad fire’ /súwà/ + rope bad /mpù/ + /ímí/ [súwămí] ‘bad rope’ /íká/ [mpĭká] lxxx white bird ‘the white bird’ What is observed about the examples given above is that the second of two contiguous vowels disappears as a result of an elision process but the tone of such a vowel survives to show up on the surving vowel of such a cluster. Note, however that the underlying LHL tone pattern is preserved although that means the LH being squashed on to a single vowel. Similarly, when glide formation (see the last example) turns an underlying high vowel into a nonsyllabic glide. Mid tone or unmarked tone does not disappear. It merely gets shunted on to the next syllabic segment. Once again, the underlying LHL tone pattern is preserved by having a rising tone on the first available vowel. lxxxi CHAPTER FIVE SUMMARY, CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 5.0 Introduction This chapter sets out to give a summary of the entire work, conclusion and some recommendations. 5.1 Summary Bura is spoken in two adjacent states in the North-eastern part of Nigeria. Native speakers of the language are found in Adamawa and Borno State, particularly in Gwoza, Damboa District (Borno State) and Duhu and Gulak (Adamwa State). Sociolinguistically, the people have their own unique culture and a monarchical system of government. Christianity, Islam, and African traditional Religion (ATR) are the religions practiced by the people. Among the festivals are ‘maize harvest’ festival which performed before fresh corn can be eaten and ‘mbal’ festival for both men and women who have attained the age of marriage. The economic system of Bura hinges on agriculture and transportation. Bura (Pabir) is under Bura group of biu Mandara branch of Chadic sub-family of the Afro-Asiatic phylum in the genetic tree. The project is theoretically modelled according to the principles of generative phonology. Meanwhile, the data used lxxxii for the project were collected from native speakers of the language. The data were then analyzed using the principles of data analysis identified by generative phonologists. This project deals with the sound inventory of Bura. Bura attests thirty consonants and seven vowel sounds including seven nasal vowels. Apart from liquids and nasals, which occur word-initial, medial and final, other consonants occur word-initial and medial. Similarly, /i/, /u/, /e/, /o/ and /a/ occur wordinitial, medial and final while // occur in word medial and final position. The language has three register tones High [/], Low [\] and Mid [(unmarked). The syllable inventory of Bura has three basic structures which are CV, CCV, CVC. We also examine the phonological processes of the language. The phonological processes of Bura were examined under two broad headings. Syllable structure processes and euphonic processes. The former concerns deletion/elision and insertion/epenthesis where as the latter’s focus is assimilation and vowel harmony. The elision rule of Bura affects the second of two contiguous vowels across word boundary. The assimilatory process of Bura is regressive or anticipatory. lxxxiii The syllable and tonal processes were discussed in this project. Bura has monosyllabic, disyllabic, and trissylabic words structured distinctively. It has fourteen (14) syllable processes which are: CV, CVC, CCVC, CVCV, CCV, VCV, CCVCV, CCVCVC, CVCVV, CVCVC, CVCVCV, CCVCVCV,, CVCVCVCV, and VCVCV. In addition to the syllable processes, Bura has nine tonal configurations or patterns given as follows: High-High, High-Mid, High-Low, Low-Low, Low-High, Low-Mid, Low-HighLow, Mid-Mid, Mid-Low. The tonal patterns are reduced to a tonal melody of H,L,M,HL,HM,LM,ML,LHL, and MM. Tone polarization and stability are properties of Bura tonal inventory. 5.2 Conclusion The problem of Nigerian Government and Society is the ignorance of phonological study of native languages. This has led to negative effect and languages are less developed because they (speakers of Nigerian languages) have negative attitude, towards their languages. The Aspects of Bura Phonology is of immense significance to the development of language change of negative attitude because this case study embraces the value of language, culture, the speakers and environment. lxxxiv 5.3 Recommendations Despite the work done in various ways, the following recommendations will be useful. Public and Private Sectors should involve in the development of minority languages without being biased. The Federal Government should make the people imbibe their various indigenous languages by enforcing/introducing various indigenous languages in primary schools, secondary schools. At the higher institutions, the study of native languages should be of more standard and professional job opportunities that are incentive should be made available to zeal up a high interest rate of the people in this field. Language research institutes should be funded and necessary materials should be made available in the institute, for the linguists and the Department of Linguistics and Nigerian Languages all over the federation for both majority and minority languages. Also, native speakers should be encouraged to get trained in learning and teaching various indigenous languages. Finally, each native speaker in the nationhood should imbibe the culture of speaking, writing and learning through the indigenous in order to encourage increase of size in culture, population, economy and language. Therefore, native languages must be the first, and other languages should follow. lxxxv REFERENCES Aitchison, J. (2001). Language Change: Progress or Decay? Third Edition. UK: Cambridge University Press. Chomsky, N. and M. Halle (1968). The Sound Pattern of English. New York: Harper and Row. Clark, J.C., Yallop and J. Fletcher (2007). An Introductory to Phonetics and Phonology. Third Edition. UK: Blackwell. Comorie, B. (ed.) (1989). The World’s Major Languages Revised Edition, London and New York: Routledge. Crystal, D. (1987). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language. New York: Cambridge University Press. _____________ (2003). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language . Second Edition. New York: Cambridge University Press. Davenport, M. and S. J. Hannahs (2005). Introducing Phonetics and Phonology. Second Edition. London: Hodder Arnold. Hoffmann, C. (1963). A Grammar of Bura Language. London: OUP. Hoffmann, C. (1976). ‘The Languages of Nigerian by Language Family’. In Hansford, G. (et al) Studies in Nigeria Languages. Accra: Longman. lxxxvi Hyman, L. (1975). Phonology: Theory and Analysis. New York: Holt Rinehart and Winston. Katamba, F. (1989). An Introduction to Phonology. New York: Longman. Kenstowicz, M. (1994). Phonology in Generative Grammar. Cambridge, Mass: Basil Blackwell. Oyebade, F. (2008). A Course in Phonology. Second Edition. Ijebu-Ode: Shebiotimo Press. Ruhlen, M. (1991). A Guide to the World’s Languages. Volume 1. London: Edward Arnold. Wente-Lukas, R. (1985). Handbook of Ethnic Units in Nigeria. London: OUP. Schuh, R. G. (1978). ‘Tones Rules’. In Fromkin, V.A. (ed.) Tone: A Linguistics Survey. New York: Academic Press. Vaughan, J.H. (1970). ‘Caste Systems in the Western Sudan in Tunde, A. and L. Plotnicov (eds.) Social Stratification in Africa. New York: Free Press. Yule, G. (1996). The Study of Language. Second Edition. UK: Cambridge University Press. lxxxvii lxxxviii