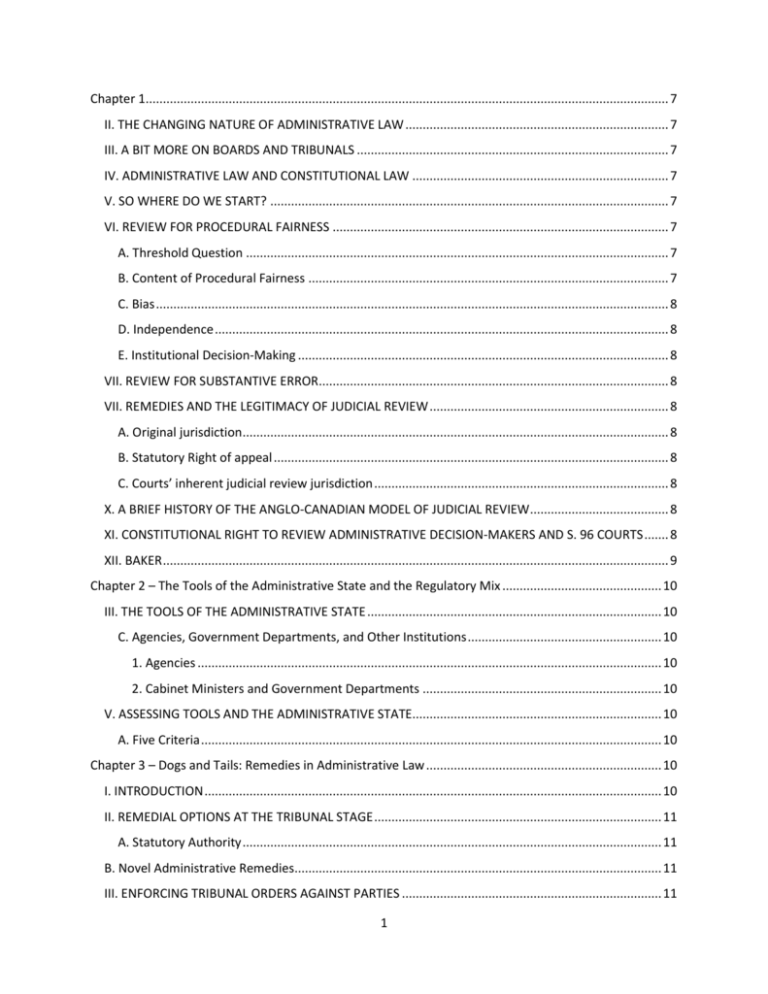

institutional fairness

advertisement