Supporting document to the “European Territorial Vision

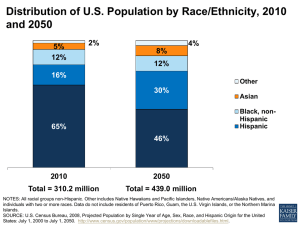

advertisement