An Anti-Oppression Education

advertisement

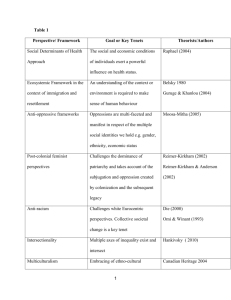

An Anti-Oppression Education 2012 An Anti-Oppression Education A Literature Review Katie Nielsen Kisko University of Toronto, OISE An Anti-Oppression Education 2012 Anti-oppression education must be taught in schools across the country to help students and teachers end the repetition of oppression within society. The literature I have read and chosen to review are five journal articles and two websites. Each of these articles and sites deals with anti-oppression education and how anti-oppression educators can teach students how to recognize oppression, and end the repetitive cycle of oppressive education in Canada. Each article identifies all resources available for students in the form of textbooks, curricula, and stories as partial. They encourage students and teachers to recognize the impartiality and question what is missing, what is unsaid, what is unheard and develop a critical response as to what this excluded information tells us about our society and about our history. It further encourages students and teachers to find the missing voices, listen to these voices, and re-evaluate our society and our country’s history in order to understand ourselves. Through constructivism pedagogy, self-reflection and critical discourse anti-oppression education can be taught and will assist students and teachers to become agents of social change, and of their own learning. The first point I would like to make is that curricula and the resources we use to teach the curriculum is partial. In any resource, story or recount there is always a missing voice, another side that has not been heard or that has been silenced. The Center of Anti-Oppression Education states that “curriculum cannot help but be partial.” They insist that “learning needs to involve refusing to be comfortable with what we already know and what we are coming to know.” Kumashiro (2001) says that “all students come to school with partial knowledges … [and] the school curriculum often does little to address these partial knowledges” (4). He also contends that “History textbooks continue to silence the narrative or authorial voice [which] implies that the account being told is objective and impartial” (4). Materials such as these privilege the hegemonic version of history. Kumashiro (2002) outlines that “anti-oppressive educators have long recognized the problematic nature of biased, non-inclusive curricula that are Eurocentric, male centered, heterosexist, or class biased. By focusing on only certain stories and perspectives such curricula normalize and privilege certain groups in society while marginalizing others” (70). He expresses the need for inclusive curricula that can help social differences and affirm how one feels about oneself. Many countries are looking at this issue, and addressing it by making teachers developers of the curriculum. For example in Kumashiro’s article, Preparing Teachers for Anti-Oppressive Education: International Movements, Brazil is allowing teachers to construct a three phase curriculum; Study of Reality, Organization of Knowledge, and Application of Knowledge. Thus, the curricula is dealing with social issues within the school’s community, making learning authentic and based on real life issues that students can relate to and including all voices within the community. Tupper (2007) in her article 1 An Anti-Oppression Education 2012 From Care-Less to Care-Full: Education for Citizenship in School and Beyond, recognizes that the Social Studies curriculum in Canada is also impartial. She suggests “that there is indifference, a lack of concern, and even negligence caught up in its construction and that because of this, many students leave their classrooms without fully understanding what it might mean to be and live as a citizen” (259). Therefore, the first part of teaching an anti-oppressive education is recognizing that the curriculum, and the resources made available to students are impartial and in need to be critiqued. My second point that I would like to make is that students and teachers must be aware and must reflect on the “hidden curriculum.” The hidden curriculum is what students learn unintentionally from the exclusion and the silences that occur in the classroom, in the curriculum and in the resources that are available. The Center for Anti-Oppressive Education notes that: “students learn results not only from what teachers teach intentionally, but also from what teachers teach unintentionally and often unknowingly, and different students ‘learn’ different things, depending on the lenses they use to make sense of their experiences. These hidden lessons about the subject matter, about schooling, and about broader social relations are always permeating our schools, emerging from our silences, behaviours, curricular structures, institutional rules, cultural values, and so forth.” Kumashiro (2001) adds that silence and exclusion are significant parts of the “hidden curriculum” (5). Which begs the question that Kumashiro et al. (2004) asks, “what voices have we yet to hear as we articulate what it means to prepare teachers in anti-oppressive ways?” (260). Kumashiro (2002) suggests teachers and students look for hidden curricula and analyze its implications. For example, in English class, Kumashiro (2001) suggests students “learn to read for silences and the effects of those silences on the “meaning” of a text… educators can teach that the partiality of texts is exactly what makes texts useful for anti-oppressive education” (7). Overall, it is imperative that students and teachers reflect on the hidden curriculum; that teachers understand what Kumashiro (2001) states “[that] the hidden curriculum is no less important than the formal one, and thus anti-oppressive teacher education involves focusing observations, support, and evaluations… on what is being taught and learned intentionally and visibly as on what is being taught and learned unintentionally and indirectly” (11). The third point that I would like to make, is that to teach anti-oppression education one must use the principles of constructivism pedagogy. The principles include teachers using rich tasks in the classroom that are authentic to students, that promote authentic interactions in class, that involve discussions, critical thinking, questioning, rich dialogue, inquiry, and experiences that connect to their real life. The 1 An Anti-Oppression Education 2012 classroom is a class of learning for both the student and the teacher. The teacher is no longer the “information depositor” but the facilitator and guide to his or her students who are active agents of their own learning. Learning is authentic with a mixture of face-to-face learning and online education or use of computer technology. Though none of the articles mention the constructivism pedagogy they all state the need for the tools that make up this pedagogy. For example, Paulo Freire in his work, Pedagogy of the Oppressed mentions the importance of dialogue, praxis, action, conscientization (developing consciousness), lived experience, and use of metaphor when teaching anti-oppressive education. In Van Gorder’s (2007) Pedagogy for the Children of the Oppressors, he states that “educators of the privileged can proactively encourage conscientizacao by generating an attitude of awareness through critical reflection, a prerequisite for liberative education” (15). He continues to say that “through conscientizacao both the privileged and the oppressed become ‘masters of their own thinking’” (15) which is essentially the goal of constructivism pedagogy. We need to teach students to be critical thinkers, to acknowledge there is a reason why certain voices are silenced and to find out why. We need to ask questions that are in-depth and thought provoking. For example, such questions as Kumashiro (2001) suggests: What story about [Canada] does the presence of these voices (and the absence of Other voices) tell us? When we add different voices, how does the story change? What knowledges and identities and practices do different configurations of voices make possible? Which stories justify the status quo? Which stories challenge the marginalization of certain groups and identities in society? (6) Not only do we need to ask questions about other we also need to ask questions of ourselves and take time to reflect. Questions such as Tupper (2007) suggests, “What privileges do I enjoy? How am I less or more privileged than others and why? What are the historical conditions that contributed to these privileges? What are the implications of this for my own experiences of citizenship?” (262). Journaling, auto-biographies, and written essays, as examples, all can help students question themselves, question others and deal with the crisis that comes with studying anti-oppressive education. Kumashiro (2002) suggests that students analyze their own identities and life experiences and how privilege or lack of privilege influenced their K-12 schooling experiences. He suggests students make connections between school and the communities they live in and compare them to their readings. He also mentions research projects addressing issues of inequity in local schools with educators. He also suggests that students draw two parallel analyses where they find readings that mirror their own experiences and readings that differ from their own experiences. Lastly, he suggests skits where students experience the difference 1 An Anti-Oppression Education 2012 between being the stereotyper with intent to harm and playing the stereotyper with the intent to critique. Not only are these great ways to reflect on self but they help students overcome the crisis that is inevitable when learning anti-oppressive education. It may also help them recognize their need or desire to resist anti-oppressive education and overcome it. Overall, these experiences are authentic and help students understand their purpose thus allowing them to be more willing to participate. Finally, teachers should also reflect on themselves and their practice. Kumashiro (2001) suggests teachers not only ask themselves what worked in their lesson but “what did this lesson make possible and impossible? In what ways did it enable repetition, crisis, change, and so forth?” (10). Overall, the tasks involved in constructivism pedagogy mirror the tasks involved in anti-oppressive education. I think this pedagogy should be used to teach in anti-oppressive ways based on the suggestions made through these articles and sites. The fourth point I found important, is that anti-oppressive education must look beyond what is written and said. Kumashiro (2001) states that “anti-oppressive education involves constantly looking beyond what it is we teach and learn… look beyond what is being learned and what is already known” (6-7). Education is no longer about repetition, “education involves learning something different, learning something new, learning something that disrupts one’s common-sense view of the world. The crisis that results from unlearning, then, is a necessary and desirable part of anti-oppressive education” (8). He concludes by stating that: Anti-oppressive education works against common-sense views of what it means to teach. Teachers must move beyond their pre-conceived notions of what it means to teach, and students must move beyond their current conceptions of what it means to learn. Antioppressive education involves constantly re-examining and troubling the forms of repetition that play our in one’s practices and that hinder attempts to challenge oppressions. It involves desiring and working through crisis rather than avoiding and masking it. It involves contesting the standards that currently define education in the disciplines. And it involves imagining new possibilities for who we are and can be (9). We need to resist repetition, and begin to question and analyze our readings, our resources and our practices. We need to provide students with opportunities to “look beyond the theories and begin to explore the possibilities for challenging oppression that the field of research has yet to articulate (Kumashiro, 76). Lastly, as Tupper (2007) states, we need to “move beyond curricular “boxes” and limited ways of engaging in the world” (270). We need to make living connections, discover new meanings, and new ways of looking at the world. Through anti-oppressive education, or ‘care-full’ 1 An Anti-Oppression Education 2012 citizenship we need to interrogate the conditions of oppression and privilege and with the tools outlined in these articles teach students and teachers how to be active agents of social change and stop the inequities that exist in our society. From reading all of these articles and sites, I have determined that teaching anti-oppressive education is not easy but it is possible. We first need to recognize that our curriculum, our resources and our knowledges are impartial. We then need to explore what is missing. We also need to be aware of the hidden curriculum and what we are teaching our students through our silences and our exclusions. Next we need to teach our students using the constructivism pedagogy where students can be active agents of their own learning, thus discovering and constructing new knowledges instead of just repeating what is already known. Working through crisis, dealing with the tough emotions that are inevitable when dealing with anti-oppression and looking beyond what it is we teach and learn I think that we can all be successful in teaching and learning anti-oppressive education. I think in combination the literature is good. I think that Kumashiro gives a lot of wonderful and useful tasks that can be implemented in any classroom. What I would like to see in further research are case studies of work being done in and across Canada and how it is making a difference! 1