FUNCTIONS of the LYMPHATIC SYSTEM

advertisement

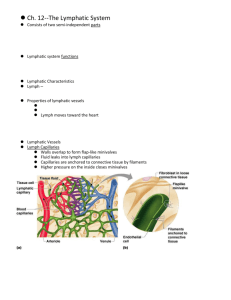

Lymphatic system Lymphatic System: Facts, Functions & Diseases Kim Ann Zimmermann, LiveScience Contributor | February 08, 2013 03:22pm ET The primary function of the lymphatic system is to transport lymph, a clear, colorless fluid containing white blood cells that helps rid the body of toxins, waste and other unwanted materials. Lymphatic comes from the Latin word lymphaticus, meaning "connected to water," as lymph is clear. The lymphatic system, which is a subset of the circulatory system, has a number of functions, including the removal of interstitial fluid, the extracellular fluid that bathes most tissue. It also acts as a highway, transporting white blood cells to and from the lymph nodes into the bones, and antigen-presenting cells to the lymph nodes. Description of the lymphatic system The lymphatic system is a network of tissues and organs that primarily consists of lymph vessels, lymph nodes and lymph. The tonsils, adenoids, spleen and thymus are all part of the lymphatic system. There are 600 to 700 lymph nodes in the human body that filter the lymph before it returns to the circulatory system. The spleen, which is largest lymphatic organ, is located on the left side of the body just above the kidney. Humans can live without a spleen, although people who have lost their spleen to disease or injury are more prone to infections. The thymus, which stores immature lymphocytes and prepares them to become active T cells, is located in the chest just above the heart. Tonsils are large clusters of lymphatic cells found in the pharynx. Although tonsillectomies occur much less frequently today then they did in the 1950s, it is still among the most common operations performed and typically follows frequent throat infections. When bacteria are recognized in the lymph fluid, the lymph nodes make more infection-fighting white blood cells, which can cause swelling. The swollen nodes can sometimes be felt in the neck, underarms and groin. Unlike blood, which flows throughout the body in a continue loop, lymph flows in only one direction — upward toward the neck — within its own system. It flows into the venous blood stream through the subclavien veins, which are located on either sides of the neck near the collarbones. Plasma leaves the cells once it has delivered its nutrients and removed debris. Most of this fluid returns to the venous circulation through the venules and continues as venous blood. The remainder becomes lymph. Lymph leaves the tissue and enters the lymphatic system through specialized lymphatic capillaries. About three-quarters of these capillaries are superficial capillaries that are located near the surface of the skin. There are also deep lymphatic capillaries that surround most of the body’s organs. There are two drainage areas that make up the lymphatic system. The right drainage area handles the right arm and chest. The left drainage area clears all of the other areas of the body, including both legs, the lower trunk, the upper left portion of the chest, and the left arm. Lymph Lymph is a fluid derived from blood plasma. It is pushed out through the capillary wall by pressure exerted by the heart or by osmotic pressure at the cellular level. Lymph contains nutrients, oxygen, and hormones, as well as toxins and cellular waste products generated by the cells. As the interstitial fluid accumulates, it is picked up and removed by lymphatic vessels that pass through lymph nodes, which return the fluid to the venous system. As the lymph passes through the lymph nodes, lymphocytes and monocytes enter it. At the level of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, lymph has a milky consistency that is attributable to fatty acids, glycerol, and rich fat content. Lacteals are lymph vessels that transport intestinal fat and are localized to the GI tract.[1, 5, 3] Lymphatic vessels Lymphatic capillaries are blind-ended tubes with thin endothelial walls (only a single cell in thickness). They are arranged in an overlapping pattern, so that pressure from the surrounding capillary forces at these cells allows fluid to enter the capillary (see the image below). The lymphatic capillaries coalesce to form larger meshlike networks of tubes that are located deeper in the body; these are known as lymphatic vessels. Lymph capillaries in spaces. Blind-ended lymphatic capillaries arise within interstitial spaces of cells near arterioles and venules. The lymphatic vessels grow progressively larger and form 2 lymphatic ducts: the right lymphatic duct, which drains the upper right quadrant, and the thoracic duct, which drains the remaining lymphatic tributaries. Like veins, lymphatic vessels have 1-way valves to prevent any backflow (see the image below). The pressure gradients that move lymph through the vessels come from skeletal muscle action, smooth muscle contraction within the smooth muscle wall, and respiratory movement.[1, 6, 2, 5, 4] Lymphatic 1-way valves. Lymph nodes Lymph nodes are bean-shaped structures that are widely distributed throughout the lymphatic pathway, providing a filtration mechanism for the lymph before it rejoins the blood stream. The average human body contains approximately 600-700 of them, predominantly concentrated in the neck, axillae, groin, thoracic mediastinum, and mesenteries of the GI tract. Lymph nodes constitute a main line of defense by hosting 2 types of immunoprotective cell lines, T lymphocytes and B lymphocytes. Lymph nodes have 2 distinct regions, the cortex and the medulla. The cortex contains follicles, which are collections of lymphocytes. At the center of the follicles is an area called germinal centers that predominantly host B-lymphocytes while the remaining cells of the cortex are T-lymphocytes. Vessels entering the lymph nodes are called afferent lymphatic vessels and, likewise, those exiting are called efferent lymphatic vessels (see the image below). Lymph node structure. Extending from the collagenous capsule inward throughout the lymph node are connective tissue trabeculae that incompletely divide the space into compartments. Deep in the node, in the medullary portion, the trabeculae divide repeatedly and blend into the connective tissue of the hilum of the node. Thus the capsule, the trabeculae, and the hilum make up the framework of the node. Within this framework, a delicate arrangement of connective tissue forms the lymph sinuses, within which lymph and free lymphoid elements circulate. A subcapsular or marginal sinus exists between the capsule and the cortex of the lymph node. Lymph passes from the subcapsular sinus into the cortical sinus toward the medulla of the lymph node. Medullary sinuses represent a broad network of lymph channels that drain toward the hilum of the node; from there, lymph is collected into several efferent vessels that run to other lymph nodes and eventually drain into their respective lymphatic ducts (see the image below).[1, 6] Lymph drainage flow; lymphatic duct anatomy. Thymus The thymus is a bilobed lymphoid organ located in the superior mediastinum of the thorax, posterior to the sternum. After puberty, it begins to decrease in size; it is small and fatty in adults after degeneration. The primary function of the thymus is the processing and maturation of T lymphocytes. While in the thymus, T lymphocytes do not respond to pathogens and foreign organisms. After maturation, they enter the blood and go to other lymphatic organs, where they help provide defense. Structurally, the thymus is similar to the spleen and lymph nodes, with numerous lobules and cortical and medullary elements. It also produces thymosin, a hormone that helps stimulate maturation of T lymphocytes in other lymphatic organs.[2, 5, 3, 4] Spleen The spleen, the largest lymphatic organ, is a convex lymphoid structure located below the diaphragm and behind the stomach. It is surrounded by a connective tissue capsule that extends inward to divide the organ into lobules consisting of cells, small blood vessels, and 2 types of tissue known as red and white pulp. Red pulp consists of venous sinuses filled with blood and cords of lymphocytes and macrophages; white pulp is lymphatic tissue consisting of lymphocytes around the arteries. Lymphocytes are densely packed within the cortex of the spleen. The spleen filters blood in much the same way that lymph nodes filter lymph. Lymphocytes in the spleen react to pathogens in the blood and attempt to destroy them. Macrophages then engulf and phagocytose damaged cells and cellular debris. The spleen, along with the liver, eradicates damaged and old erythrocytes from the blood circulation. Like other lymphatic tissue, it produces lymphocytes in an immunologic response to offending pathogens.[5, 3, 4] Therefore, the spleen conducts several important functions, as follows: It serves as a reservoir of lymphocytes for the body It filters blood It plays an important role in red blood cell and iron metabolism through macrophage phagocytosis of old and damaged red blood cells It recycles iron by sending it to the liver It serves as a storage reservoir for blood It contains T lymphocytes and B lymphocytes for immunologic response Tonsils Tonsils are aggregates of lymph node tissue located under the epithelial lining of the oral and pharyngeal areas. The main areas are the palatine tonsils (on the sides of the oropharynx), the pharyngeal tonsils (on the roof of the nasopharynx; also known as adenoids), and the lingual tonsils (on the base of the posterior surface of the tongue). Because these tonsils are so closely related to the oral and pharyngeal airways, they may interfere with breathing when they become enlarged. The predominance of lymphocytes and macrophages in these tonsillar tissues offers protection against harmful pathogens and substances that may enter through the oral cavity or airway.[1, 2] Diseases of the lymphatic system include lymphedema, lymphoma, lymphadenopathy, lymphadenitis, filariasis, splenomegaly, and tonsillitis. Lymphedema Lymphedema results when the lymphatic system cannot adequately drain lymph, resulting in an accumulation of fluid that causes swelling. It may be either primary or secondary. Primary lymphedema is an inherited condition that occurs as a result of impaired or missing lymphatic vessels; it may be present at birth, may develop with the onset of puberty, or may occur in adulthood, with no apparent causes Secondary lymphedema is basically acquired regional lymphatic insufficiency, which may occur as a consequence of any trauma, infection, or surgical procedure that disrupts the lymphatic vessels or results in the loss of lymph nodes Treatment consists of compression bandages or pneumatic stockings to alleviate the swelling after appropriate diagnosis is made.[7, 4] Lymphoma Lymphoma is a medical term used for a group of cancers that originate in the lymphatic system. Lymphomas usually begin with malignant transformation of the lymphocytes in lymph nodes or bunches of lymphatic tissue in organs like the stomach or intestines. Hodgkin lymphoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma are the 2 major categories of lymphoma, characterized by enlargement of lymph nodes, usually present in the neck. Symptoms of lymphoma include chronic fatigue, weak immune function, weight loss, and night sweats.[4] Lymphadenopathy Lymphadenopathy is a lymphatic disorder in which the lymph nodes become swollen or enlarged as a consequence of an infection. For example, swollen lymph nodes in the neck may occur as a result of a throat infection or sinus infection.[3] Lymphadenitis Lymphadenitis is an inflammation of the lymph node that is due to a bacterial infection of the tissue in the node, which causes swelling, reddening, and tenderness of the skin overlying the lymph node.[3] Filariasis Filariasis is a lymphatic system disorder that results from a parasitic infection that causes lymphatic insufficiency.[3] Splenomegaly Splenomegaly, or enlarged spleen, is a lymphatic system disorder that develops as a result of a viral infection, such as mononucleosis. Tonsillitis Tonsillitis is caused by an infection of the tonsils (the lymphoid tissues present in the back of the oral cavity). The tonsils help filter out bacteria; when infected, they become swollen and inflamed, leading to sore throat, fever, and difficulty and pain while swallowing.[3] FUNCTIONS of the LYMPHATIC SYSTEM The main functions of the lymphatic system are as follows: the main function of the lymphatic system is to collect and transport tissue fluids from the intercellular spaces in all the tissues of the body, back to the veins in the blood system; it plays an important role in returning plasma proteins to the bloodstream; digested fats are absorbed and then transported from the villi in the small intestine to the bloodstream via the lacteals and lymph vessels. new lymphocytes are manufactured in the lymph nodes; antibodies and anti (manufactures in the lymph nodes) assist the body to build up an effective immunity to infectious diseases; lymph nodes play an important role in the defence mechanism of the body. They filter out micro-organisms (such as bacteria) and foreign substances such as toxins, etc. it transports large molecular compounds (such as enzymes and hormones) from their manufactured sites to the bloodstream.