SOC 604 Goodsell - BYU Sociology

advertisement

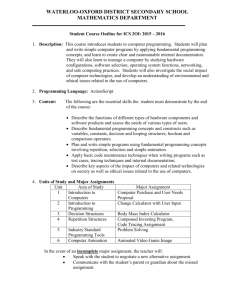

1 SOC 604 - Ethnographic Research Techniques Winter 2013 Section 001: 2002 JFSB on M W from 8:45 am - 10:00 am Name: Todd Goodsell Office Phone: 801-422-3336 Office Location: 2029 JFSB Email: goodsell@byu.edu Office Hours: M,W 3:15 pm M,W 10:00 am T 6:30 pm Or By Appointment Course Information Description Rationale, methods, and limitations of qualitative research; includes participant observation and hermeneutic skills. Prerequisite Soc 600 Material Item BYU CUSTOM - THE HOBO : THE SOCIOLOGY OF THE HOMELESS MAN Required by N, ANDERSON, ISBN: 9780740932571 ETHNOGRAPHER'S METHOD Required by A, STEWART, ISBN: 9780761903949 Vendor Price (new) Price (used) BYU Bookstore $0.00 $0.00 BYU Bookstore $26.00 $19.50 BYU Bookstore $19.00 $14.25 BYU Bookstore $16.95 $12.75 WRITING ETHNOGRAPHIC FIELDNOTES 2E Required by R, EMERSON, Edition 2 ISBN: 9780226206837 LEARNING FROM STRANGERS Required by R, WEISS, ISBN: 9780684823126 Learning Outcomes Full Range of Methodologies Graduates will know the full range of methodologies, the basic epistemological assumptions associated with each, the criteria for evaluating quality research, and how to select and implement the appropriate method to test a hypothesis or address a research question. Code and Interpret Graduates will know how to code and interpret qualitative data. 2 Schedule Date MJan 07 Topics Introduction TJan 08 WJan 09 Response 1 Purposes of Qualitative Research Su Jan 13 MJan 14 Readings & Assignments Geertz, Clifford. 1973. Thick Description: Toward an Interpretive Theory of Culture. Chapter 1 (p. 3-30) in The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays. New York: BasicBooks. Response 2 Ethics TJan 15 Berg, Bruce. 2012. Ethical Issues. Chapter 3 (p. 61-104) in Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences. 8th ed. Boston: Pearson. Response 3 WJan 16 Ethnography: Examples MJan 21 Martin Luther King Jr. Holiday Anderson, Nels. 1923. The Hobo: The Sociology of the Homeless Man. Provo, UT: BYU Custom. (beginning to p. 122) TJan 22 Response 4 WJan 23 Anderson, Nels. 1923. The Hobo: The Sociology of the Homeless Man. Provo, UT: BYU Custom. ( p. 123 to end) Su Jan 27 Response 5 MJan 28 Haenfler, Ross. 2004. Rethinking Subcultural Resistance: Core Values of the Straight Edge Movement. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 33(4):406-436. TJan 29 Response 6 WJan 30 Ethnography Stewart, Alex. 1998. The Ethnographer's Method. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. (beginning to p. 29) 3 Date Topics Readings & Assignments Su Feb 03 Response 7 MFeb 04 Stewart, Alex. 1998. The Ethnographer's Method. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage (p. 29 to end) TFeb 05 Response 8 WFeb 06 Emerson, Robert M., Rachel I. Fretz, and Linda L. Shaw. 2011. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (beginning to p. 44) Su Feb 10 Response 9 Berg, Bruce. 2012. Field Notes (p. 229-238) in Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences. 8th ed. Boston: Pearson. MFeb 11 Patton, Michael Quinn. 2002. Fieldwork: The DataGathering Process (p. 302-306) in Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods. 3rd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. TFeb 12 Reponse 10 WFeb 13 Emerson, Robert M., Rachel I. Fretz, and Linda L. Shaw. 2011. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (p. 171-199) MFeb 18 Presidents Day Holiday TFeb 19 Monday Instruction WFeb 20 (What is a good ethnography?) Reponse 11 Emerson, Robert M., Rachel I. Fretz, and Linda L. Shaw. 2011. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (p. 201-248) Response 12 Wacquant, Loic. 2002. Scrutinizing the Street: Poverty, Morality, and the Pitfalls of Urban Ethnography. American Journal of Sociology 107(6):1468-1532. Su Feb 24 Response 13 MFeb 25 Anderson, Elijah. 2002. The Ideologically Driven Critique. American Journal of Sociology 107(6):1533-1550. Duneier, Mitchell. 2002. What Kind of Combat Sport Is 4 Date Topics Readings & Assignments Sociology? American Journal of Sociology 107(6):15511576. Newman, Katherine. 2002. No Shame: The View from the Left Bank. American Journal of Sociology 107(6):15771599. TFeb 26 Response 14 Duneier, Mitchell. 2011. How Not to Lie with Ethnography. Sociological Methodology 41(1):1-11. WFeb 27 Fieldnotes Su Mar 03 MMar 04 Response 15 Qualitative interviewing Participant observation: Fieldnotes and analysis due TMar 05 WMar 06 Weiss, Robert S. 1994. Learning from Strangers: The Art and Method of Qualitative Interview Studies. New York: Free Press. (beginning to p. 60) Response 16 (Sampling in a Qualitative Study) Patton, Michael Quinn. 2002. Purposeful Sampling (p. 230246) in Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods. 3rd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Small, Mario Luis. 2009. 'How Many Cases Do I Need?': On Science and the Logic of Case Selection in Field-Based Research. Ethnography 10(1):5-38. Su Mar 10 Response 17 MMar 11 Weiss, Robert S. 1994. Learning from Strangers: The Art and Method of Qualitative Interview Studies. New York: Free Press. (p. 61-150) TMar 12 Response 18 Atkinson, Robert. 1998. Transcription (p. 54-57) in The Life Sory Interview. Thousand Oaks, Sage. WMar 13 (Transcribing Audiorecordings) Kvale, Steinar and Svend Brinkmann. 2009. Transcribing Interviews (p. 180-187) in InterViews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing. Los Angeles: Sage. 5 Date Topics Readings & Assignments Su Mar 17 Response 19 MMar 18 Weiss, Robert S. 1994. Learning from Strangers: The Art and Method of Qualitative Interview Studies. New York: Free Press. (p. 151-end) TMar 19 Response 20 Kvale, Steinar and Svend Brinkmann. 2009. Preparing for Interview Analysis (p. 189-193) InterViews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing. Los Angeles: Sage. WMar 20 Interviewing Su Mar 24 MMar 25 TMar 26 WMar 27 Su Mar 31 MApr 01 TApr 02 Response 21 Oral History, Biographical Research, and Narrative Analysis Portelli, Alessandro. 1991. The Death of Luigi Trastulli: Memory and the Event. Chapter 1 (p. 1-26) in The Death of Luigi Trastulli and Other Stories: Form and Meaning in Oral History. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. Rosenthal, Gabriele. 2007. Biographical Research. Chapter 3 (p. 48-64) in Qualitative Research Practice. Edited by Clive Seale, Giampietro Gobo, Jaber F. Gubrium, and David Silverman. Los Angeles: Sage. Response 22 Response 22 Bornat, Joanna. 2007. Oral History. Chapter 2 (p. 34-47) in Qualitative Research Practice. Edited by Clive Seale, Giampietro Gobo, Jaber F. Gubrium, and David Silverman. Los Angeles: Sage. Coding & Memoing Response 23 Lieblich, Amia, Rivka Tuval-Mashiach, and Tamar Zilber. 1998. [Narrative Analysis] p. 12-14, 62-63, 112-114 in Narrative Research: Reading, Analysis, and Interpretation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Response 24 6 Date WApr 03 Topics Focus groups Su Apr 07 Readings & Assignments Morgan, David L. 1996. Focus Groups. Annual Review of Sociology 22:129-152. Response 25 Harper, Douglas. 2002. Talking about Pictures: A Case for Photo Elicitation. Visual Studies 17(1):13-26. MApr 08 Visual Ethnography Harper, Douglas. 2003. Framing Photographic Ethnography: A Case Study. Ethnography 4(2):241-266. Interviewing: Transcript due Findings Section TApr 09 Response 26 Garcia, Angela Cora, Alecea I. Standlee, Jennifer Bechkoff, and Yan Cui. 2009. Ethnographic Approaches to the internet and Computer-Mediated Communication. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 38(1):52-84. WApr 10 Online Qualitative Research Methods Hookway, Nicholas. 2008. 'Entering the Blogosphere': Some Strategies for Using Blogs in Social Research. Qualitative Research 8(1):91-113. Murthy, Dhiraj. 2008. Digital Ethnography: An Examination of the Use of new Technologies for Social Research. Sociology 42(5):837-855. Su Apr 14 Response 27 Term Paper Opens Anderson, Leon. 2006a. Analytic Autoethnography. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 35(4):373-395. Ellis, Carolyn S. and Arthur P. Bochner. 2006. Analyzing Analytic Autoethnography: An Autopsy. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 35(4):429-449. Final Exam: MApr 15 2002 JFSB Anderson, Leon. 2006b. On Apples, Oranges, and Autopsies: A Response to Commentators. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 35(4):450-465. 3:00pm - 6:00pm Autoethnography Optional: Atkinson, Paul. 2006. Rescuing Autoethnography. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 35(4):400-404. Charmaz, Kathy. 2006. The Power of Names. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 35(4):396-399. Vryan, Kevin D. 2006. Expanding Analytic Autoethnography and Enhancing Its Potential. Journal of Contemporary 7 Date Topics Readings & Assignments Ethnography 35(4):405-409. Denzin, Norman K. 2006. Analytic Autoethnography, or Deja Vu all Over Again. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 35(4):419-428. Term Paper Due Interviewing: Analysis due Extra Credit WApr 24 Assignment Descriptions Findings Section Due: Monday, Apr 08 at 9:00 am Interviewing Due: Wednesday, Mar 20 at 9:00 am Fieldnotes Due: Wednesday, Feb 27 at 9:00 am Fieldnotes Coding & Memoing Due: Wednesday, Mar 27 at 9:00 am Coding & Memoing Term Paper Due: Wednesday, Apr 24 at 12:15 pm Term Paper Response 1 Due: Tuesday, Jan 08 at 11:59 pm Response 1 Response 2 Due: Sunday, Jan 13 at 11:59 pm Response 2 Response 3 Due: Tuesday, Jan 15 at 11:59 pm Response 3 Term Paper Closes 8 Response 4 Due: Tuesday, Jan 22 at 11:59 pm Response 4 Response 5 Due: Sunday, Jan 27 at 11:59 pm Response 5 Response 6 Due: Tuesday, Jan 29 at 11:59 pm Response 6 Response 7 Due: Sunday, Feb 03 at 11:59 pm Response 7 Response 8 Due: Tuesday, Feb 05 at 11:59 pm Response 8 Response 9 Due: Sunday, Feb 10 at 11:59 pm Response 9 Reponse 10 Due: Tuesday, Feb 12 at 11:59 pm Response 10 Reponse 11 Due: Monday, Feb 18 at 11:59 pm Response 11 Response 12 Due: Tuesday, Feb 19 at 11:59 pm Response 12 Response 13 Due: Sunday, Feb 24 at 11:59 pm Response 13 9 Response 14 Due: Tuesday, Feb 26 at 11:59 pm Response 14 Response 15 Due: Sunday, Mar 03 at 11:59 pm Response 15 Response 16 Due: Tuesday, Mar 05 at 11:59 pm Response 16 Response 17 Due: Sunday, Mar 10 at 11:59 pm Response 17 Response 18 Due: Tuesday, Mar 12 at 11:59 pm Response 18 Response 19 Due: Sunday, Mar 17 at 11:59 pm Response 19 Response 20 Due: Tuesday, Mar 19 at 11:59 pm Response 20 Response 21 Due: Sunday, Mar 24 at 11:59 pm Response 21 Response 22 Due: Tuesday, Mar 26 at 11:59 pm Response 22 Response 22 Due: Tuesday, Mar 26 at 11:59 pm Response 22 10 Response 23 Due: Sunday, Mar 31 at 11:59 pm Response 23 Response 24 Due: Tuesday, Apr 02 at 11:59 pm Response 24 Response 25 Due: Sunday, Apr 07 at 11:59 pm Response 24 Response 26 Due: Tuesday, Apr 09 at 11:59 pm Response 26 Response 27 Due: Sunday, Apr 14 at 11:59 pm Response 27 Participation Due: Wednesday, Apr 17 at 11:59 pm Participation Extra Credit Due: Monday, Apr 15 at 11:59 pm Take the end-of-the-semester, online evaluation and release your name Point Breakdown Assignments Percent of Grade Homework 48.34% Findings Section 15.11% Interviewing 15.11% Fieldnotes 15.11% Coding & Memoing 3.02% Final Exam 30.21% Term Paper 30.21% Response Papers 16.92% Response 1 0.6% 11 Assignments Percent of Grade Response 2 0.6% Response 3 0.6% Response 4 0.6% Response 5 0.6% Response 6 0.6% Response 7 0.6% Response 8 0.6% Response 9 0.6% Reponse 10 0.6% Reponse 11 0.6% Response 12 0.6% Response 13 0.6% Response 14 0.6% Response 15 0.6% Response 16 0.6% Response 17 0.6% Response 18 0.6% Response 19 0.6% Response 20 0.6% Response 21 0.6% Response 22 0.6% Response 22 0.6% Response 23 0.6% Response 24 0.6% Response 25 0.6% Response 26 0.6% Response 27 0.6% Participation 4.53% Participation 4.53% Extra Credit 0% Extra Credit 0% University Policies Course Policies Attendance and Participation 12 Attendance and participation are required. The instructor may take attendance. Attendance and participation may be used as a factor in determining final grades. Be ready to learn. Show up on time and do not leave until the class is over. Turn off your cell phone or pager before class starts, or put them on “vibrate.” When it is class time and when you are in class, you should be part of the class. Do not do things that distract other students (e.g., study for other classes, read the newspaper, eat lunch, take phone calls, surf the Internet, text message, or chat with your neighbor [unless instructed to do so]). These are standards you are expected to follow in many workplaces. Have study buddies in class, in case you are sick and need someone to give you notes or turn in your work. You should also have study buddies with whom you can study for exams. All work must be done by you, for this class. You may not, for example, double-count work you did for another class as also work for this class. The academic and moral standards of this class stipulate that you actually do the assigned work. For example, while you may discuss homework assignments with other class members, what you write should be based on your own reading, study, and thought. (I do not want another class in which several students turn in virtually the same essay. Rather than trying to figure out who wrote the original essay, I am likely to assume that everyone just copied or paraphrased off of everyone else—and that’s going to be bad for everyone’s grades.) Turning in Assignments Turn in assignments through BYU Learning Suite. If BYU Learning Suite is not working or if you have to turn something in late, print it out looking professional, and submit it in hard copy. Turn in assignments by handing them to Dr. Goodsell directly, or by giving them to the Sociology Department secretaries (2008 JFSB), or by sliding them under the door of Dr. Goodsell’s office (2029 JFSB). Do not leave anything in the plastic bin in the hallway outside Dr. Goodsell’s office (2029 JFSB). It is not secure. Assignments are due as indicated in BYU Learning Suite. Assignments turned in after the due date/time will be penalized. If you are turning something in late, please write on the assignment the day and time you turned it in so I know how much the assignment will be penalized. (Otherwise, I guess when you turned it in.) Each class member is granted one opportunity during the semester to turn one written assignment in late for full credit. To take advantage of this, you must email Dr. Goodsell before the assignment is due and provide the following information: State that you will be turning the assignment in late. State when (day & time) you will turn it in (must be within 48 hours of when it is due). Notwithstanding this policy, no assignments will be accepted after the last class period of the semester. You may always turn in assignments early (e.g., if you have to be out of town), and if you do, the late policy will not apply. Portions of assignments that are only in-class cannot be made up. Under exceptional circumstances (e.g., flu pandemic), typical protocols may be waived. Please do not come to class or visit the professor if you are sick and contagious. (Consider using the telephone or email.) Per university directive, a note from your doctor is not required. If you have some kind of exceptional circumstance (disease, disaster, disability, etc.), please talk to the instructor as soon as possible to make other arrangements. Records Save your work. If you find a problem with the evaluation of an assignment or test, do not wait until the end of the semester to bring it up with Dr. Goodsell; please discuss it with Dr. Goodsell as soon as possible. Dr. Goodsell will return assignments and/or post scores online. Dr. Goodsell will also post final grades prior to the grade submission deadline. Because of this, Dr. Goodsell is less likely to accommodate grade change requests after the grade submission deadline. Communication 13 You are responsible to attend class, keep your contact information (including email address) up to date with the university, and check your registered email account regularly and frequently. If you don’t do this, you may miss important class announcements and instructions. Help with Writing FHSS Writing Lab 1051 JFSB 801-422-4454 http://fhsswriting.byu.edu fhss-writinglab@byu.edu This class is coordinated with the FHSS Writing Lab. Writing tutors can help you with any written assignment for this class. Take drafts of papers in as early as possible so you have time to revise them. To prepare for a visit with a writing tutor, take A hard copy of the assignment A hard copy of your draft A list of questions or concerns you have about your draft Either make an appointment or just drop in. You may also meet with Dr. Goodsell to discuss your ideas about course material and assignments. If you want Dr. Goodsell to give you feedback on a draft of your work, you must also provide him with a “golden ticket” from the FHSS Writing Lab showing that you have gone through a draft with a writing tutor at least once since Dr. Goodsell has last seen a draft of this assignment. Also, the deadline for giving Dr. Goodsell a draft of an assignment is two class periods before the assignment is due. This gives him at least a couple of days to provide written feedback to you and it gives you at least a couple of days to revise. Use ASA style unless the particular assignment requires otherwise. A brief guide to ASA style is found at: http://www.asanet.org/Quick%20Style%20Guide.pdf The full ASA Style Guide is available in the FHSS Writing Lab. Careers If you have goals for graduate school and/or careers, you’ll enjoy your classes more because you will see how they are relevant. You are welcome to visit with me to talk about your educational and career plans. You can come alone or you can bring a friend. You don’t have to have goals yet; you can talk with us if you are just trying to figure things out. We’ll give you some suggestions about what you can do right now so you can be better prepared for graduate school and/or a career. Think about your undergraduate education as a “package” that includes the following: University core A major A minor or a double-major Internships Teaching and/or research assistantships Pre-professional and academic clubs Classes specifically related to your educational and career goals Other experiences (e.g., the Honors Program, service projects, international programs) Preparation for graduate school I don’t give you points for meeting with me to talk about education or careers. However, good students will typically talk with their professors about educational and career plans. This can get you started doing that. 14 Flexibility Changes may be made to the course (including to the syllabus) to account for emergent needs or for clarification. Requirements may change in the event of a policy statement from administrators. Honor Code In keeping with the principles of the BYU Honor Code, students are expected to be honest in all of their academic work. Academic honesty means, most fundamentally, that any work you present as your own must in fact be your own work and not that of another. Violations of this principle may result in a failing grade in the course and additional disciplinary action by the university. Students are also expected to adhere to the Dress and Grooming Standards. Adherence demonstrates respect for yourself and others and ensures an effective learning and working environment. It is the university's expectation, and my own expectation in class, that each student will abide by all Honor Code standards. Please call the Honor Code Office at 422-2847 if you have questions about those standards. Sexual Harassment Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 prohibits sex discrimination against any participant in an educational program or activity that receives federal funds. The act is intended to eliminate sex discrimination in education and pertains to admissions, academic and athletic programs, and university-sponsored activities. Title IX also prohibits sexual harassment of students by university employees, other students, and visitors to campus. If you encounter sexual harassment or gender-based discrimination, please talk to your professor or contact one of the following: the Title IX Coordinator at 801-422-2130; the Honor Code Office at 801-422-2847; the Equal Employment Office at 801-422-5895; or Ethics Point at http://www.ethicspoint.com, or 1-888-2381062 (24-hours). Student Disability Brigham Young University is committed to providing a working and learning atmosphere that reasonably accommodates qualified persons with disabilities. If you have any disability which may impair your ability to complete this course successfully, please contact the University Accessibility Center (UAC), 2170 WSC or 4222767. Reasonable academic accommodations are reviewed for all students who have qualified, documented disabilities. The UAC can also assess students for learning, attention, and emotional concerns. Services are coordinated with the student and instructor by the UAC. If you need assistance or if you feel you have been unlawfully discriminated against on the basis of disability, you may seek resolution through established grievance policy and procedures by contacting the Equal Employment Office at 422-5895, D-285 ASB. Academic Honesty The first injunction of the Honor Code is the call to "be honest." Students come to the university not only to improve their minds, gain knowledge, and develop skills that will assist them in their life's work, but also to build character. "President David O. McKay taught that character is the highest aim of education" (The Aims of a BYU Education, p.6). It is the purpose of the BYU Academic Honesty Policy to assist in fulfilling that aim. BYU students should seek to be totally honest in their dealings with others. They should complete their own work and be evaluated based upon that work. They should avoid academic dishonesty and misconduct in all its forms, including but not limited to plagiarism, fabrication or falsification, cheating, and other academic misconduct. Plagiarism Intentional plagiarism is a form of intellectual theft that violates widely recognized principles of academic integrity as well as the Honor Code. Such plagiarism may subject the student to appropriate disciplinary action administered through the university Honor Code Office, in addition to academic sanctions that may be applied by an instructor. Inadvertent plagiarism, which may not be a violation of the Honor Code, is nevertheless a form of intellectual carelessness that is unacceptable in the academic community. Plagiarism of any kind is completely contrary to the established practices of higher education where all members of the university are expected to acknowledge the original intellectual work of others that is included in their own work. In some cases, plagiarism may also involve violations of copyright law. Intentional Plagiarism-Intentional plagiarism is the deliberate act of representing the words, ideas, or data of another as one's own without providing proper attribution to the author through quotation, reference, or footnote. Inadvertent Plagiarism-Inadvertent plagiarism involves the inappropriate, but non-deliberate, use of another's words, ideas, or data without proper attribution. 15 Inadvertent plagiarism usually results from an ignorant failure to follow established rules for documenting sources or from simply not being sufficiently careful in research and writing. Although not a violation of the Honor Code, inadvertent plagiarism is a form of academic misconduct for which an instructor can impose appropriate academic sanctions. Students who are in doubt as to whether they are providing proper attribution have the responsibility to consult with their instructor and obtain guidance. Examples of plagiarism include: Direct Plagiarism-The verbatim copying of an original source without acknowledging the source. Paraphrased Plagiarism-The paraphrasing, without acknowledgement, of ideas from another that the reader might mistake for the author's own. Plagiarism Mosaic-The borrowing of words, ideas, or data from an original source and blending this original material with one's own without acknowledging the source. Insufficient AcknowledgementThe partial or incomplete attribution of words, ideas, or data from an original source. Plagiarism may occur with respect to unpublished as well as published material. Copying another student's work and submitting it as one's own individual work without proper attribution is a serious form of plagiarism. Respectful Environment "Sadly, from time to time, we do hear reports of those who are at best insensitive and at worst insulting in their comments to and about others... We hear derogatory and sometimes even defamatory comments about those with different political, athletic, or ethnic views or experiences. Such behavior is completely out of place at BYU, and I enlist the aid of all to monitor carefully and, if necessary, correct any such that might occur here, however inadvertent or unintentional. "I worry particularly about demeaning comments made about the career or major choices of women or men either directly or about members of the BYU community generally. We must remember that personal agency is a fundamental principle and that none of us has the right or option to criticize the lawful choices of another." President Cecil O. Samuelson, Annual University Conference, August 24, 2010 "Occasionally, we ... hear reports that our female faculty feel disrespected, especially by students, for choosing to work at BYU, even though each one has been approved by the BYU Board of Trustees. Brothers and sisters, these things ought not to be. Not here. Not at a university that shares a constitution with the School of the Prophets." Vice President John S. Tanner, Annual University Conference, August 24, 2010 Inappropriate Use Of Course Materials All course materials (e.g., outlines, handouts, syllabi, exams, quizzes, PowerPoint presentations, lectures, audio and video recordings, etc.) are proprietary. Students are prohibited from posting or selling any such course materials without the express written permission of the professor teaching this course. To do so is a violation of the Brigham Young University Honor Code. Deliberation Guidelines To facilitate productive and open discussions about sensitive topics about which there are differing opinions, members of the BYU community should: (1) Remember that we are each responsible for enabling a productive, respectful dialogue. (2)To enable time for everyone to speak, strive to be concise with your thoughts. (3) Respect all speakers by listening actively. (4) Treat others with the respect that you would like them to treat you with, regardless of your differences. (5) Do not interrupt others. (6) Always try to understand what is being said before you respond. (7) Ask for clarification instead of making assumptions. (8) When countering an idea, or making one initially, demonstrate that you are listening to what is being said by others. Try to validate other positions as you assert your own, which aids in dialogue, versus attack. (9) Under no circumstances should an argument continue out of the classroom when someone does not want it to. Extending these conversations beyond class can be productive, but we must agree to do so respectfully, ethically, and with attention to individuals' requests for confidentiality and discretion. (10) Remember that exposing yourself to different perspectives helps you to evaluate your own beliefs more clearly and learn new information. (11) Remember that just because you do not agree with a person's statements, it does not mean that you cannot get along with that person. (12) Speak with your professor privately if you feel that the classroom environment has become hostile, biased, or intimidating. Adapted from the Deliberation Guidelines published by The Center for Democratic Deliberation. (http://cdd.la.psu.edu/education/The%20CDD%20Deliberation%20Guidelines.pdf/view?searchterm=deliberatio n%20guidelines)