Boumediene-Bush Precedent Cases

advertisement

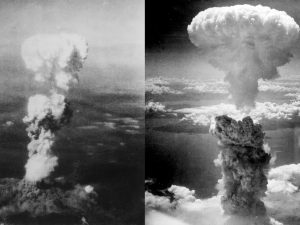

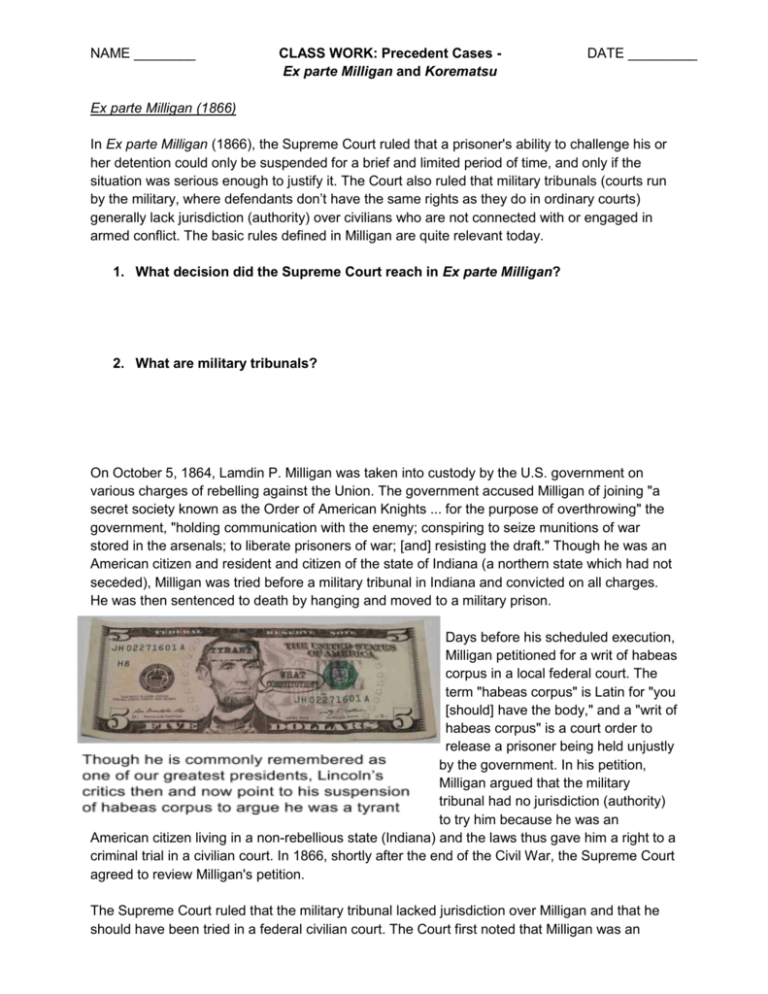

NAME ________ CLASS WORK: Precedent Cases Ex parte Milligan and Korematsu DATE _________ Ex parte Milligan (1866) In Ex parte Milligan (1866), the Supreme Court ruled that a prisoner's ability to challenge his or her detention could only be suspended for a brief and limited period of time, and only if the situation was serious enough to justify it. The Court also ruled that military tribunals (courts run by the military, where defendants don’t have the same rights as they do in ordinary courts) generally lack jurisdiction (authority) over civilians who are not connected with or engaged in armed conflict. The basic rules defined in Milligan are quite relevant today. 1. What decision did the Supreme Court reach in Ex parte Milligan? 2. What are military tribunals? On October 5, 1864, Lamdin P. Milligan was taken into custody by the U.S. government on various charges of rebelling against the Union. The government accused Milligan of joining "a secret society known as the Order of American Knights ... for the purpose of overthrowing" the government, "holding communication with the enemy; conspiring to seize munitions of war stored in the arsenals; to liberate prisoners of war; [and] resisting the draft." Though he was an American citizen and resident and citizen of the state of Indiana (a northern state which had not seceded), Milligan was tried before a military tribunal in Indiana and convicted on all charges. He was then sentenced to death by hanging and moved to a military prison. Days before his scheduled execution, Milligan petitioned for a writ of habeas corpus in a local federal court. The term "habeas corpus" is Latin for "you [should] have the body," and a "writ of habeas corpus" is a court order to release a prisoner being held unjustly by the government. In his petition, Milligan argued that the military tribunal had no jurisdiction (authority) to try him because he was an American citizen living in a non-rebellious state (Indiana) and the laws thus gave him a right to a criminal trial in a civilian court. In 1866, shortly after the end of the Civil War, the Supreme Court agreed to review Milligan's petition. The Supreme Court ruled that the military tribunal lacked jurisdiction over Milligan and that he should have been tried in a federal civilian court. The Court first noted that Milligan was an American citizen who was a resident of a non-rebellious state, Indiana, during the Civil War. The Court also noted that Milligan was not connected to the armed forces and had not been fighting Union forces when he was captured. Therefore, his actions could not be realistically described as rebellion. Accordingly, the Court also argued Milligan was denied basic constitutional rights when his writ of habeas corpus was denied and his case was sent to a military tribunal rather than an ordinary court. Together, the Court concluded that the laws and Constitution demand that Milligan, as with any other civilian, not be tried by a military tribunal if, as in this case, there is a civilian court available instead. To find otherwise, the Court said, would mean that "republican government is a failure, and there is an end of liberty regulated by law." The Court warned that "Martial law" in such a system "destroys every guarantee of the Constitution, and effectually renders the 'military independent of and superior to the civil power.'" Ex parte Milligan was a clear statement on behalf of basic rights and liberties most Americans take for granted today. 3. What reasons did the Supreme Court give for siding with Milligan? 4. Is what Milligan was described as doing consistent with your definition of a rebellion? 5. Do you think Lincoln’s decision to arrest and deny Milligan’s habeas corpus rights was constitutional? Explain your answer with evidence. Korematsu v. United States (1944) concerns outweighed the rights. In Korematsu v. United States, the Supreme Court sided with the government’s policy of removing Japanese-Americans from their homes and relocating them to internment camps. By a 6-3 majority, the Court accepted the U.S. military's argument that the loyalties of some Japanese Americans resided not with the United States but with their ancestral country (Japan), and that because separating "the disloyal from the loyal" was not realistic or possible, the internment order had to apply to all Japanese Americans within the restricted area. Balancing the country's stake in the war and national security against the "suspect" denial of rights of a particular racial group, the Court decided that the nation's security Constitution's promise of equal Writing for the majority, Justice Hugo Black held that although "all legal restrictions which curtail the civil rights of a single racial group are immediately suspect" and subject to tests of "the most rigid scrutiny," not all such restrictions are inherently unconstitutional. "Pressing public necessity," he wrote, "may sometimes justify the existence of such restrictions; racial antagonism never can." 1. What decision did the Supreme Court reach in Korematsu v. United States? 2. What explanation did the Supreme Court provide for making this decision? Early in World War II, on February 19, 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, granting the U.S. military the power to ban tens of thousands of American citizens of Japanese ancestry from areas deemed critical to domestic security. Promptly exercising the power granted by Executive Order 9066, the military then issued an order banning "all persons of Japanese ancestry, both alien and non-alien" from a designated coastal area stretching from Washington State to southern Arizona, and quickly set up internment camps to hold the Japanese-Americans for the duration of the war. In defiance of the order, Fred Korematsu, an American-born citizen of Japanese descent, refused to leave his home in San Leandro, California. After his conviction, he appealed, and in 1944 his case reached the Supreme Court. 3. What was Executive Order 9066, and why did President Roosevelt issue it? Justice Robert Jackson issued an angry, yet intelligent, dissent. "Korematsu ... has been convicted of an act not commonly thought a crime," he wrote. "It consists merely of being present in the state whereof he is a citizen, near the place where he was born, and where all his life he has lived." The nation's wartime security concerns, he contended, were not adequate to strip Korematsu and the other internees of their constitutionally protected civil rights. In the second half of his dissent, however, Jackson admitted that ultimately, in times of war, the military should maintain the power to arrest citizens -- and that, possessing no executive power, there was little the judicial branch could do to stop it. Nonetheless, he resisted the Court's willingness to lend its reputation and authority to justify the military's actions, and contended that the majority decision struck a "far more subtle blow to liberty" than did the order itself: "A military order, however unconstitutional, is not apt to last longer than the military emergency... But once a judicial opinion rationalizes such an order to show that it conforms to the Constitution, or rather rationalizes the Constitution to show that the Constitution sanctions such an order, the Court for all of time has validated the principle of racial discrimination..." The Court's decision in Korematsu, loudly criticized by many at the time and generally condemned by historians ever since, has never been explicitly overturned. However, a report issued by Congress in 1983 declared that the decision had been "overruled in the court of history," and the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 contained a formal apology -- as well as provisions for monetary reparations -- to the Japanese Americans interned during the war. In 1998, President Bill Clinton awarded Fred Korematsu the Presidential Medal of Freedom. 4. Do you agree more with the majority opinion or the dissenting opinion in this case? Explain your answer with evidence. 5. Do you think Roosevelt’s decision to detain Japanese-Americans and deny them habeas corpus rights was constitutional? Explain your answer with evidence.