unit overview. - Achievement First

advertisement

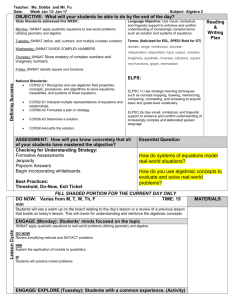

5th Grade, Unit 6: Writing Ancient Polynesian Navigation Introduction, Overview, Aims, and Calendar Table of Contents Writing class unit introductions and overviews Assessment and Summative Assessment Aims for writing class Unit calendar for writing class Grade 5, Unit 6 Overview – Ancient Polynesian Navigation In this informational-based writing unit, scholars will utilize their scientific knowledge about the movement of the earth and stars to explain how ancient Polynesians were able to navigate vast open areas of water. While not the primary focus of this unit, this unit will also tangentially leverage history’s focus on early civilizations. During this unit, scholars will be flexing their research muscles for the first time. This unit intentionally builds the skills that scholars will use during the Unit 8, a more independent research unit. Three of the ten Common Core Standards are explicitly rooted in research, and this skill is one scholars will continue to hone throughout high school and college. This unit is also the last one in 5th grade that introduces new 6th grade specific PBA thresholds. Future units continue to give scholars additional at-bats, sometimes in different genres, at previously introduced thresholds, and scholars that are meeting all of these can be pushed up towards sixth grade thresholds. Specifically, in terms of new thresholds, this unit focuses on incorporating both quoted evidence and paraphrased evidence. Because this is the first official time scholars are differentiating between quoted and paraphrased evidence, making sure scholars understand the value of giving credit where credit is due and the cost of plagiarism is critical. Additionally, scholars will continue to improve the quality of their analysis. By this point in the year, scholars should be attempting to clarify or explain most of their evidence. As with many fifth grade thresholds, we are teaching scholars to clarify or explain all of their evidence, but we are evaluating their ability to do this most of the time. While there are no new grammar points to be introduced in this unit, scholars should be independently writing with all of the fifth grade grammar concepts consistently by the end of the year. These include proper capitalization, end punctuation, and comma usage (in a series, after introductory phrases, and in compound sentences). Scholars not doing these things consistently and independently should have one of these as a focus skill until it is mastered and then move onto the next skill. Scholars who consistently and independently write with these focus skills should begin working on sixth grade skills. As scholars will be gathering information for this paper, some early days will resemble reading days more than writing days. The resources are set up in an order to build natural inquiry for scholars. Having resources set up in a webquest format can provide 5th graders with an accessible foray into research. Common Core State Standards: Writing CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.5.2 Write informative/explanatory texts to examine a topic and convey ideas and information clearly. CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.5.2a Introduce a topic clearly, provide a general observation and focus, and group related information logically; include formatting (e.g., headings), illustrations, and multimedia when useful to aiding comprehension. CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.5.2b Develop the topic with facts, definitions, concrete details, quotations, or other information and examples related to the topic. CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.5.2c Link ideas within and across categories of information using words, phrases, and clauses (e.g., in contrast, especially). CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.5.2d Use precise language and domain-specific vocabulary to inform about or explain the topic. CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.5.2e Provide a concluding statement or section related to the information or explanation presented CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.5.7 Conduct short research projects that use several sources to build knowledge through investigation of different aspects of a topic. CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.5.8 Recall relevant information from experiences or gather relevant information from print and digital sources; summarize or paraphrase information in notes and finished work, and provide a list of sources. CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.5.9 Draw evidence from literary or informational texts to support analysis, reflection, and research. CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.5.9b Apply grade 5 Reading standards to informational texts CCSS.ELA-Literacy.L.4.1g Correctly use frequently confused words (e.g., to, too, two; there, their).* CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.5.4 Produce clear and coherent writing in which the development and organization are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience. (Grade-specific expectations for writing types are defined in standards 1–3 above.) CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.5.5 With guidance and support from peers and adults, develop and strengthen writing as needed by planning, revising, editing, rewriting, or trying a new approach. (Editing for conventions should demonstrate command of Language standards 13 up to and including grade 5 here.) CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.5.6 With some guidance and support from adults, use technology, including the Internet, to produce and publish writing as well as to interact and collaborate with others; demonstrate sufficient command of keyboarding skills to type a minimum of two pages in a single sitting. CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.5.10 Write routinely over extended time frames (time for research, reflection, and revision) and shorter time frames (a single sitting or a day or two) for a range of discipline-specific tasks, purposes, and audiences. CCSS.ELA-Literacy.L.5.2e Spell grade-appropriate words correctly, consulting references as needed. CCSS.ELA-Literacy.L.5.3a Expand, combine, and reduce sentences for meaning, reader/listener interest, and style. New PBA Thresholds: Evidence: Selection: Presentation: 2 Evidence selected is used co rrectly indirectly (paraphrased) and directly (quo tatio ns) when appro priate. Student may cho o se to o nly paraphrase (as a natural precurser to direct quo tatio ns). Evidence: Interpretation: Analysis: 3 A ttempts to clarify and explain the meaning o f mo st evidence as needed . Essential Questions: How can we use technology to explain some of the mysteries of early civilizations? How can we find and incorporate evidence into our writing? Why is it important to give an author credit if we use someone else’s words and ideas? Enduring Understandings: Early civilizations created their own technology, and through modern technology, we can better understand ancient technology. We, as researchers, can use technology to find information, but we must give the original author credit when we incorporate their words and ideas into our writing. Unit Goals Scholars will write an informational essay that: Provides some general framing about the content (Evidence: Contextualization: Framing: 3) Is driven by a clear and focused topic sentence that addresses the prompt and states a relevant claim in third person (Argument: Position: Thesis: 2) Uses one and two word transitions to clarify relationships (Argument: Organization: Flow: 2) Begins to have ‘reasonable essay structure (Argument: Organization: Structure: 3-4) Selects evidence connected to the topic of the paragraph (Evidence: Selection: Choice: 3) Uses both quoted and paraphrased evidence (Evidence: Selection: Presentation:2) Attempts to clarify and explain most evidence (Evidence: Interpretation: Analysis: 3) Attempts to establish and maintain a formal tone in writing (Language: Style: Register: 3) Uses active verbs and academic language (Language: Word Choice: Range and Quality: 3) Unit Assessments Below are descriptions of the diagnostic, formative, and summative assessments for Unit 4. The formative assessments may be used daily, weekly, and in combination to measure scholars’ progress toward unit goals. The summative assessment should be delivered uniformly across the grade in order to accurately measure scholars’ achievement. Diagnostic PBA Data from Unit 4 and 5 IA 2 and 3 Data Formative Ongoing writing on Google Docs Exit Tickets Unit Checkpoints Summative PBA Performance Task EOY IA Summative Assessments Process Based Assessment: How were the Ancient Polynesians able to traverse large bodies of water and find land without modern navigation tools? Primary Resources: The Art of The Tautai: Polynesian Wayfinder: (9:35) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=joP-v7NxQZU Never Lost: http://www.exploratorium.edu/neverlost/ Polynesia’s Genius Navigators: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/ancient/polynesia-genius-navigators.html OPTIONAL: Secrets of Ancient Navigators http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/ancient/secrets-of-ancient-navigators.html See secondary resources attached below. On-Demand Assessment: (Choice) How were the people of Easter Island able to make and move the moai without modern technology? http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2012/06/120622-easter-island-statues-moved-hunt-lipo-science-rocked/ http://travel.nationalgeographic.com/travel/world-heritage/easter-island/ http://www.livescience.com/37277-easter-island-statues-walked-there.html How and why did the Ancient Egyptians make mummies? http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/ancient/mummies-101.html http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/ancient/making-mummies.html http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/ancient/afterlife-ancient-egypt.html http://www.si.edu/Encyclopedia_SI/nmnh/mummies.htm IA Correlation: On IA 4, scholars will integrate information from multiple sources, very similar to the Smarter Balanced assessment. Writing Class AIMs 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. SWBAT annotate the prompt. SWBAT provide some general framing about the topic after watching a short video clip. SWBAT define plagiarism and articulate the rationale for citing evidence. SWBAT distinguish between paraphrased and quoted evidence. SWBAT decide when to quote and when to paraphrase evidence. SWBAT accurately paraphrase evidence. OPTIONAL:SWBAT distinguish between relevant and irrelevant evidence. OPTIONAL: SWBAT skim for relevant evidence. SWBAT determine paragraph topics and identify relevant quoted and paraphrased evidence from notes. SWBAT craft a thesis and topic sentences for body paragraphs. SWBAT select the best relevant quoted and paraphrased evidence for each body paragraph. SWBAT properly punctuate quotations. OPTIONAL Extension: SWBAT properly cite quotations. SWBAT clarify and explain evidence while drafting body paragraphs. SWBAT incorporate general framing when drafting the introduction. SWBAT draft a conclusion that links to the introduction. SWBAT incorporate a variety of one and two word transitions that clarify the relationships between ideas. SWBAT revise for word choice, including correct use of academic language, incorporation of vocabulary words, and colorful use of active verbs. SWBAT edit for personal grammar goals, including capitalization, end punctuation, commas in a series, commas after introductory phrases, and commas in compound sentences. SWBAT edit for formal tone as needed. SWBAT demonstrate mastery of 5th grade PBA thresholds by publishing their PBA. SWBAT describe and reflect on the research process from the PBA Writing Aims Calendar Week 1 Day 1 – The Art of Tautai Aims: SWBAT annotate the prompt. SWBAT provide some general framing about the topic after watching a short video clip. (The Art of the Tautui) Week 2 Day 6 – Aim: SWBAT determine paragraph topics and identify relevant quoted and paraphrased evidence from notes. Day 2 – Never Lost Day 3 – Never Lost Aim: SWBAT define plagiarism and articulate the rationale for citing evidence. Aim: SWBAT decide when to quote and when to paraphrase evidence. SWBAT distinguish between paraphrased and quoted evidence. SWBAT accurately paraphrase evidence. Day 4 -Polynesia’s Genius Navigators Aim: SWBAT decide when to quote and when to paraphrase evidence. Day 5 – Flex Day OPTIONAL: Secrets of Ancient Navigators SWBAT accurately paraphrase evidence. Aim: OPTIONAL: SWBAT distinguish between relevant and irrelevant evidence. OPTIONAL: SWBAT skim for relevant evidence. Day 7 – Day 8 – Day 9 – Day 10 – Aim: SWBAT craft a thesis and topic sentences for body paragraphs. Aim: SWBAT properly punctuate quotations. Aim: SWBAT clarify and explain evidence while drafting body paragraph 1. Aim: SWBAT clarify and explain evidence while drafting body paragraphs 2-3. SWBAT select the best quoted and paraphrased evidence for each paragraph. OPTIONAL Extension: SWBAT properly cite quotations. Week 3 Day 11 – Day 12 – Day 13 – Day 14 – Flex Day Day 15 – Aim: SWBAT incorporate general framing when drafting the introduction. Aim: SWBAT incorporate a variety of one and two word transitions that clarify the relationships Aim: SWBAT edit for personal grammar goals, including capitalization, end punctuation, commas in a Aim: Aim: Publish PBA. Final PBAs must be submitted by the end of class today. between ideas. SWBAT draft a conclusion that links to the introduction. SWBAT revise for word choice, including correct use of academic language, incorporation of vocabulary words, and colorful use of active verbs. series, and commas in compound sentences. SWBAT edit for formal tone as needed. Week 4: Performance Task: Great Wall of China or Egyptian Pyramids Day 16 – Day 17 – Performance Day 18 – Performance Task Task Aim: SWBAT describe Day 2 of independent and reflect on the Day 1 of independent scholar work time for the research process from scholar work time for the performance task. the PBA (with the intent performance task. of applying that Aim: knowledge to the Aim: performance task). Day 19 – Performance Task Day 3 of independent scholar work time for the performance task. Day 20 – Performance Task Day 4 of independent scholar work time for the performance task. Some Relevant Vocabulary Words IA 1 Comprehend Contribute Evidence Inference Resource Endurance Verify Billowing Sprawling IA 2 Perplexed Significant Origin Bewilderment Hardship Traditions Fathom Utterly Cunning Native Underlying IA 3 Devote Persevere Retrieve Meander Acquire Yearn Longing Wanter Wisdom Reputation Ritual Unparalleled Generation Culture Annotated Exemplar or Student Example When European explorers came to the islands in the Pacific Ocean, they were perplexed to find many of these islands already settled. Long before the Europeans arrived, the ancient Polynesians traveled all over the sprawling Pacific Ocean without modern technology like GPS. Their canoes, their use of nature to help them navigate, and their knowledge about how to find land contributed to the ancient Polynesians’ success. The canoes that the Ancient Polynesians used were not regular canoes. According to Never Lost, they were 120 feet long and made out of native Koi trees. These big canoes could carry more resources and would probably not get crushed as much in the waves. Also, these were not single canoes. They were double canoes or had outriggers. This would make them more stable in the ocean. When people tried to recreate these canoes recently, it took a long time to succeed because these weren’t easy to build. Ancient Polynesians relied on the stars and the waves to help them find their way. “Polynesian navigators orient themselves primarily by the stars, using what's called a star compass” (Never Lost). This wasn’t actually a real compass, but it was their memory of the sky and stars. They couldn’t rely on this during the day though, so they used swells. Swells are waves that have traveled a long way. Even when it is sunny and they couldn’t see the stars, Polynesians could use the swells to verify that they were still heading the right way. It is pretty incredible that the Ancient Polynesians didn’t meander or wander off course. Instead, they could travel thousands of miles in a straight line with only the stars and the waves to guide them. Finally, Polynesians knew about signs that showed that they were close to land. PBS.org says, “The surest telltale sign would be the presence of birds making flights out to sea seeking food.” Birds can’t live very far from land, so if they see birds, that is evidence that land is near. Clouds can also help people find land. “Clouds accumulate over islands, and an isolated pile of clouds on the horizon often signals the presence of land” (Never Lost). Sometimes, sunlight reflects off the white sand and lights up the bottom of clouds. Also, many islands are in groups, so if you find one of them, you can find the others. This wisdom contributed to the Polynesians’ ability to find land. Some people are utterly bewildered by the Polynesians’ unparalleled accomplishments and think that finding these tiny islands in the middle of a big ocean would be like finding a needle in a haystack, but the Polynesians did it over and over again. Without modern technology, they were able to navigate and settle the Pacific Ocean using traditions and rituals passed down from generation to generation. People today try to replicate these voyages, and they are continually amazed at what the Polynesians were able to accomplish with wooden canoes, the stars, the waves, the birds, and the clouds. Supplemental Resources 1. APPENDIX C: Origins and Migrations of the Polynesians. By: Potter, Norris W. and Kasdon, Lawrence M. and Rayson, Ann; History of the Hawaiian Kingdom, 2003, p. 185, 3p, 1 Color Photograph, 1 Map, Reading Level (Lexile): 990 http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=khh&AN=18255713&site=hrc-live History Reference Center Many centuries ago the ancestors of the Polynesian peoples came into an area known today as Oceania. It is made up of more than ten thousand islands, which modern geographers divided into three parts: Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. It is thought that these people journeyed slowly from Southeast Asia, through the islands of Indonesia, and from there to the far-flung islands of the Pacific. Settlement of Oceania During the last Ice Age (15,000 to 20,000 years ago) the ocean level was 150 to 350 feet lower than it is today. Many areas now under water were once dry land. Over this land bridge from Asia came the ancestors of the native peoples of Australia, New Guinea, and parts of Melanesia. They migrated not all at once but over a period of many centuries. Since distances between the land masses were short, these people needed only very simple boats for travel and probably were seldom out of sight of land. Centuries later, other tribal and family groups sailed farther eastward. They settled the rest of Melanesia and the islands of Micronesia and Polynesia. These explorations took place many centuries before the great Western European voyages. Settlement of Polynesia By slow stages the islands of western Polynesia were discovered and simple communities founded. Centers of culture were formed in Samoa and the Society Islands in southeastern Polynesia. Further daring expeditions would follow, toward New Zealand to the south, Hawai'i to the north, and Easter Island to the East--the great "Polynesian Triangle." The Hawaiian Islands were among the last to be discovered by the Polynesians. In the past, scholars believed that Hawai'i was first settled by Tahitians about 1000 A.D. However, archeologists have uncovered evidence that the first Hawaiians came from the Marquesas at least 500 15 years earlier. Because Hawaiian culture is so closely related to Tahitian culture, there is reason to believe that, although the first settlers came from the Marquesas, the later ones were from Tahiti. How the Polynesians Crossed the Great Ocean In what kinds of boats did the Polynesians make their amazing journeys? Long before sailors of the Mediterranean and the Atlantic dared to venture far from land, Polynesian canoes were crossing and recrossing the 2,400 miles between Hawai'i and Tahiti. From the central Pacific they sailed eastward to discover Rapa Nui (Easter Island), a distance of 2,500 miles with no in-between stopping places. For ordinary fishing and travel to nearby islands, the Polynesians used a simple canoe hollowed out of logs with the aid of stone adzes. Usually these canoes were small, although some were more than fifty feet long. A more stable craft was the outrigger canoe, made by attaching a floating ama, or outrigger, to a single canoe. The ama is a pole of light wood, fastened to the hull by two crosspieces extending outward from the hull. It rests on the surface of the water and helps to keep the canoe from tipping. With the ama, small vessels could be used for fairly long journeys even in rough water. For long voyages, two canoes were joined together by wooden crossties or by a platform pulled between them. The large twin canoes had one or two masts set in this platform. Often a deck house thatched with pandanus leaves was built on the platform for shelter from the sun and rain. When the Europeans arrived in Polynesia, they found the islanders using Tongan single canoes, which could be 150 feet long. A triangular sail was hung by the middle of one side from the mast, which was fastened to the deck or the front of the canoe. The sail, not the canoe, was reversed when the crew wished to change direction. Preparations for the Voyage When the Polynesians set out on a long voyage to a new home, they planned very carefully. First they inspected their canoes for any weaknesses. Everything had to be in perfect order for the coming battle with the mighty ocean. Then they stocked the canoe with food and water. Since their new island home might have few natural resources, they took with them seeds and food plants, pigs, dogs, and fowl. The foods for the voyage were usually cooked. Voyagers starting from atolls took ripe pandanus fruit grated into a coarse flour, cooked, dried, and packed into bundles protected by an outer wrapping of dried pandanus leaves. The voyagers starting from volcanic islands took preserved breadfruit carried in fairly large baskets and sweet potatoes that had been cooked and dried. Also onboard was dried shellfish, which could be kept indefinitely. Fowls were cooped in canoes, fed with dried coconut meat, and killed and eaten when necessary. Master fishermen caught deep-sea fish, including sharks. Food could be cooked over a fireplace laid on a bed of sand on the deck. Fresh water was carried in coconut water jugs, gourds, or lengths of bamboo. 16 After waiting for the right season of the year, they decided on the perfect day to set forth. When all the omens were favorable and the gods had been honored, they raised their mat sails, passed through the reefs, and steered for the horizon. The Crossing They had no compass or log book. They guided themselves by the sun and the stars, by the flight of the birds, by cloud formations, and by the actions of the waves and winds. Polynesian navigators knew and could name 150 or more stars. They kept track of the days by tying knots in a piece of string. Year after year these daring voyagers piloted their double canoes across the waters of the Pacific. One by one the islands of the Pacific were discovered. Some were dry and not fit for settlement. Others were green and could support life. Among the most livable of these were what are now known as the Hawaiian Islands. When the ancient Polynesians arrived in the Hawaiian Islands, they brought with them their old ways of doing things. Later, they changed them to fit the conditions of their new home. And then suddenly, for some reason still unknown, the period of the "long voyages" ended. The people who had reached Hawai'i lived apart from the rest of the world. In this period, lasting centuries, they developed their own culture. 17 After some centuries the Islands were discovered again, this time by Europeans and Americans, who brought a new god and new ways. : The darker blue area is the "Polynesian Triangle." The arrows show paths of migration to Hawai'i from the Marquesas (A.D. 300-600) and from Tahiti (A.D, 1000-1300). 18 2. The Polynesians. Explorers of the South Pacific, 2003, p. 12, 8p, 4 Color Photographs, Reading Level (Lexile): 1040 http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=khh&AN=10664885&site=hrc-live History Reference Center The Early People of Australia and New Guinea, called aborigines, went to sea on crude rafts. Then, they began making canoes out of tree bark. They used sticks-or their hands-as paddles. Very lightweight, these early canoes rode over high ocean waves without being swamped. Among the greatest ancient navigators were the Polynesians. Scientists are uncertain which island, island group, or continent was the Polynesians' original home. They have Oriental features in appearance, suggesting Asian ties, but they also resemble native peoples of South America and have certain similar customs. This led 20th-century explorer and scientist Thor Heyerdahl to believe they may have migrated westward across the Pacific from South America, rather than eastward from the Asian or Australian mainlands. To prove his theory, in 1947 Heyerdahl set out from Peru with five companions in a crude raft. If they could cross the Pacific safely to the islands of Polynesia using only sail power, it would prove ancient sailors could have done the same-an idea most scientists thought preposterous because of the distances. Heyerdahl's raft, named Kon-Tiki, was made of large, light balsa logs from the jungle of Ecuador. He and his men lashed the logs together using hemp, a rough form of rope similar to what early Native Americans might have used centuries ago. Heyerdahl refused to use metal bands or nails. He insisted on using only materials that would have been available to South Pacific seafarers many centuries before. They built a breezy deck cabin of bamboo and mounted a large, square sail on a mast. Amazingly enough, they made it to the Tuamotu Islands near Tahiti-some 4,000 miles away-in 101 days. Although the experiment did not prove the Polynesians had come originally from South America, it showed they could have. Among the Polynesians, canoe making became a practiced skill. Directed by a master craftsman of the village, groups of workers would begin with a wide tree trunk. They would scoop out the center using stone axes and seashells, leaving a thin-sided hull. To make the sides higher and more seaworthy against the surging ocean waves, they would sew boards, or strakes, along the upper edges. To bore holes in the wood, they used shark-tooth drill bits tied to sticks with animal skin cords. The work was both backbreaking and delicate. 19 If you've ever ridden in a canoe, you know that great care must be taken to keep it from capsizing-that is, turning over in the water. Polynesians faced the same problem, made worse in choppy seas. In time, the islanders discovered they could make a boat more stable by attaching a floating "arm" several feet out from one side. This balanced the boat wonderfully as it zipped over ocean swells. Canoes made in this way are called outriggers. Polynesian sailors also came to realize they could use the wind to help their canoes go. They learned to harness the wind by raising a pole from the bottom of the raft, tying a crosspiece at the top, and hanging an animal hide or woven mat from it. They worked these simple sails using ropes made of braided coconut fiber. In fair winds, they could sail 100 miles or farther in a day. The Polynesians in their outrigger canoes ventured great distances across the Pacific. Sometimes they followed birds in flight. They learned natural skills of navigation, finding their location from the position of the sun, moon, and constellations. They understood the Pacific's wind patterns and currents, and used them to their advantage. Their seafaring instincts steadily increased over the centuries. While sailing the open sea, for example, they could tell when they approached land by the look of the clouds and the scent of flowers and other wildlife on the breeze. By sailing in expeditions of many outriggers spread across miles of ocean, the Polynesians increased their likelihood of sighting one of the small, far-flung islands of the vast Pacific. Over the centuries, Polynesian canoes were made larger and larger. The natives began connecting two large canoes side-by-side, with a platform across the middle. By building a small hut on these planks, they could shelter themselves from the weather. Thus, they created some of the first "ships" in the world. Some of these vessels were longer than a modern house. Eventually, Polynesian culture spread throughout the South Pacific, from Easter Island off the South American coast to New Zealand in the west and Hawaii in the north, above the equator. Those islands, with Tahiti near the center, are the three corners of the Polynesian "triangle." However, some historians think the Polynesians also sailed the Indian Ocean and possibly reached westward to the coast of Africa. 20 3. Ridgell, Reilly Pacific Nations & Territories; 1995, p26(Click to view 'Table of Contents')4p1 Color Photograph, 1 Black and White Photograph, 1 Diagram Bess Press, Inc. 9781573060011 This article provides information on the navigation and canoe technology of Pacific Islanders. Pacific Islanders used outrigger sailing canoes. These craft were very sturdy and easily capable of open-ocean voyages. The hulls were usually made of breadfruit wood. The sail was made of woven pandanus leaves. Rope and lines for the vessel were made from coconut fibers. Polynesian canoes could be quite large, with double hulls capable of carrying 50 or more people. Micronesian canoes tended to be smaller. Early European explorers were always impressed with the seaworthiness of Pacific canoes. Even caught in a typhoon, they would at least stay afloat. (Copyright applies to all Abstracts) 820 http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=n4h&AN=18275107&site=srck5-live PART ONE: PACIFIC BACKGROUND: UNIT TWO: PEOPLING OF THE PACIFIC: CHAPTER 5: Navigation and Canoe Technology 1. Outrigger Canoes Pacific islanders used outrigger sailing canoes. These craft were very sturdy and easily capable of open-ocean voyages. The hulls were usually made of breadfruit wood. The sail was made of woven pandanus leaves. Rope and lines for the vessel were made from coconut fibers. Polynesian canoes could be quire large, with double hulls capable of carrying 50 or more people. Dogs, pigs, and chickens could be taken for stock on a new island. It was also a good idea to take coconuts, breadfruit, taro, bananas, potatoes, and other crops for planting on a new island. The canoes could hold all this easily. 21 Micronesian canoes tended to be smaller, 25 feet to 30 feet long (7.5-9 m). To tack, or change direction when sailing upwind, the whole sail could be lifted and moved to the other end. The bow would become the stem and vice versa. Early European explorers were always impressed with the seaworthiness of Pacific canoes. Even caught in a typhoon, they would at least stay afloat. Many cases have been recorded of islanders surviving a typhoon by lashing themselves to their canoe and riding out the storm. 2. Navigation Problems In navigation there are two problems. One is how to tell which direction you are going. The other is how to tell your exact position. In the open ocean, out of sight of land, these are very real problems. In the European method of navigation, a compass can be used to tell direction. The needle will point north. But this does not tell you where you are. The needle will point north regardless of your position. (Of course it will point to magnetic north, which is not the same as true north.) To find position, you must know your latitude and longitude. Latitude lines, or parallels, run east-west around the earth. They measure how far north or south of the equator you are. Longitude lines, or meridians, run north-south, meeting at the poles. They measure how far east or west you are of the prime meridian, which runs through Britain. If you know your degrees of latitude and longitude, you can locate yourself on a map. These values can be found using a sextant, an accurate watch, the proper tables, and good charts and maps. Latitude is easier to find. The North Star never moves. It is located right above the North Pole; the farther north, the higher the North Star. South of the equator, the North Star disappears. But if you are north of the equator, simply use the sextant to measure the angle of the North Star to the horizon. That gives you exact latitude. Longitude is much more difficult. You must use the sextant to take a sight of the sun exactly at noon. Then you need the proper tables and charts. Early European navigators were very poor at fixing longitude. Today there are many electronic navigation aids. Loran stations are large radio transmitters located on certain islands. They send out steady signals to help ships and planes pinpoint their locations. Various types of navigation radar are being used, and satellites are proving useful to navigation. 22 3. Islander Navigation Methods Pacific islanders didn't have compasses, sextants, watches, tables, or maps. They had no Loran stations, satellites, or radar. If below the equator, they did not even have the North Star. (They did, however, have the Southern Cross, a constellation giving a fairly accurate reading for south.) One way to navigate is to use dead reckoning. This means you start from one island and head straight in the direction of the island you want to reach. If you keep straight, you should hit the island. But ocean currents can take you off course without your knowing it. You will miss the island. Storms and squalls may also throw you off your path. Pacific island navigators have many methods for telling direction and position. For direction, the sun and stars are very useful. By their rising and setting, they give a general heading for east and west. They also serve as a directional guide to locate islands. From the time he is a small boy, a prospective navigator memorizes hundreds of star courses. He memorizes which stars to follow to get to each island from any island he might be on. If it is cloudy, the navigator can use waves to tell direction. Waves are made by wind. During the trade wind season, which is also the sailing season, the steady trade winds make steady swells or waves. These swells go in a steady direction. The navigator feels the waves under the boat. He can tell which are the steady swells coming from the northeast (or southeast below the equator). He feels the rocking of the canoe as the waves pass under. Depending on how the boat rocks, he can judge the angle of the canoe to the swells. He thus knows in which direction he is heading. Keeping track of position is more difficult. The navigator simply keeps track mentally of speed and direction to judge how far the canoe has traveled. This is also dead reckoning, and means he has to be on the lookout for currents. There are three main currents in the Pacific area we are studying. The North Equatorial Current flows east to west. The Equatorial Counter Current flows west to east just north of the equator. Below it is the South Equatorial Current that flows east to west. The navigator already knows where these and other regular currents are and can judge their strength by the shape of the waves. Waves are made by wind, and a current will change the way a wave looks. Also, while leaving an island, the navigator takes two back sightings lining up the canoe with special landmarks. The second back sight tells him how much the canoe has been affected by the current so that he may adjust his course accordingly. All this information will be in the navigator's head. The navigator also knows the location of all undersea reefs. He can recognize a reef by the shape along its edge. Once he finds a reef and recognizes which one it is, he knows his exact location. Some reefs are many miles from land, but they are valuable sea marks. Once you know your exact position, you can adjust your course. 23 Land-nesting sea birds also help navigators. These birds fish anywhere from 20-30 miles (32-48 km) from land. If a navigator spots such a bird, he knows land is close. At sunset, the birds will head in a straight line for their island. Since flat atolls can be seen from about ten miles (16 km) away at most, the birds give the navigator a bigger target and more insurance. Certain island groups had additional methods. Kiribati navigators could see islands reflected in the clouds above the islands. Marshallese navigators used the northeast swells. The steady waves would be bent by the long reefs of the Marshallese atolls. The famous Marshallese stick charts were really only used as training aids for young navigators. Today, most of this knowledge has been lost. Only in a few islands in the Central Carolines of Micronesia are there still navigators who dare to cross hundreds of miles of open ocean. Even on those islands, the skill may be dying. Many children go off to school, away from their fathers and uncles who can teach them navigation. It takes years of study and practice to become a navigator. Some of these islands have, however, experienced a revival of canoe building and navigation learning in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Whether the current revival on islands like Polowat, in Chuuk, and Satawal, in Yap, will keep such skills alive for more than a generation or two remains to be seen. As of 1992, there were approximately 90 traditional navigators of varying degrees of skill in all the islands of the Central Carolines. There were also about 50 apprentices. Vocabulary: outrigger canoes, tack, direction, position, compass, latitude, longitude, parallels, meridians, prime meridian, sextant, North Star, Loran stations, dead reckoning, northeast or southeast swell, undersea reefs 24 : Imaginary journeys of Polowat canoes showing how they use reefs and birds to stay on course. In both samples here, they head for the huge Gray Feather Bank to do some fishing, then continue either to Pik or Onoun. Both islands are about 100 miles from Polowat. Satawal, in Yap is another central Carolinian island famous for its navigation and sailing. Both islands, about 120 miles apart, visit each other frequently. 25 Man from Kapingamarangi, a Polynesian atoll in Micronesia, uses an adze to carve out a paddling canoe on Pohnpei. (Photo courtesy MRTC) 26 Outrigger sailing canoe tied up in the Polowat Lagoon, Chuuk State. (Photo by Carlos Viti) 27