Distributed Language Theory, Dialogism and Linguistic Meta

advertisement

2014-06-18

Per Linell

Distributed Language Theory, dialogism and linguistic

meta-theory

Paper presented at the International Conference on ”Finding Common Ground: Social, Ecological, and Cognitive

Perspectives on Language Use”, University of Connecticut at Storrs, June 12, 2014

1. Interactivities in Distributed Language Theory and Dialogical Theories

The purpose of this paper is to discuss a few aspects of the similarities and differences

between Distributed Language Theories (DLT; Cowley et al., 2010; Cowley, 2011) and

dialogism (”dialogical theories”; Linell, 2009). This reflects a discussion which I am

currently having together with Sune Vork Steffensen (Linell, 2013; Steffensen, forthc.;

Linell, forthc.). At the end, I will also summarise some points of a meta-theory of

language, which will substitute many dogmas in dominant structuralist and generativist

theories of language. This theory, or rather: meta-theory, will assume that language is

based on languaging rather than language systems.1

The similarities between DLT and dialogical theories, their ”common ground”, comprise,

among other things, the central role of human interactivity in life and sense-making, the

distributed nature of sense-making and meaning-making, the central role of actionperception cycles in sense-making, the primordial status of languaging over secondorder language systems, the heterogeneity of languages, the emergence (and reemergence in new generations) of languaging and language from other semiotic

practices, and undoubtedly many others.

However, here I will focus more on some possible differences between DLT and

dialogism. One point concerns assumptions about interactivities and their statuses

within the theories. I will distinguish between classical dialogism and extended

1

Ppt on language vs. languaging.

dialogism (or a broader view on interactivities). Let us differentiate between at least

three positions:

(1) Distributed Language Theory: this is largely based on organism – environment

theory, according to which the single organism (or subject, system) and its umwelt (with

its objects, processes, artefacts etc.) mutually determine each other. That is, the outer

environment does not simply function as stimuli for the organism´s reactions and

responses, but the organism has capacities to actively search for information and sense,

especially through action-perception cycles. At the same time, there is no special place in

DLT for the interaction between self and other sense-makers (”the other”).

(2) Classical dialogism (e.g. Bakhtin; Marková 2003 etc), which is defined by its

emphasis on the Self – Other relations. Self (the participant in current focus) is

interdependent with Other(s) in all sorts of sense-making, in direct or indirect

interactions.2 In addition, there is, in classical dialogism, often an emphasis on language

(or other symbolic means).

(3) Extended dialogism, based on the interactivities between both the subject (the

sense-maker in current focus) and the objects, artefacts etc in the environment, and

between the subject and other sense-makers. Essentially this amounts to an integration

of (1) and (2).

Why would a dialogist (like myself) prefer (3), i.e. both (1) and (2), to just (2)? Well,

because self-other interaction is intertwined with, and partially emerges from, a broader

organism-environment interaction. More specifically, we need other-interdependence (2)

as a necessary assumption in the theory of language/languaging, (and therefore more

generally in) communication, cognition etc. But people are also involved in an extended

interactivity with the ecosocial world (1) in general, and we need this in the language

Note that this self-other interdependency holds not only for direct interaction (as in a

conversation or direct bodily interaction) but also for solo thinking, or the activities of

the lone writer or reader. One may make a distinction between meaning-making, which

would involve (partially) conscious or accountable use of conventional signs (e.g.

language) and the more general phenomenon of sense-making, which may also include,

for example, sensory (ap)perception.

2

sciences too, because it is necessary in the explanation of the development and

maintenance of many aspects of language itself (aspects of language emergent from

interaction with the world/Umwelt we live in).

As already suggested, processes and practices of languaging are (logically and

genetically) prior to language systems (cf. Thibault, 2011: first-order languaging vs.

second-order language systems). But second-order languages are real too; as Thibault

(op.cit.: 219) points out:

”Second-order language is no less real than the dynamical properties of first-order

languaging, though it exists on a different spatiotemporal scale as a set of virtual

patterns – a structured space or contrast set of cultural possibilities that defines and

constrains the sociocognitive interactive capacities andtendencies of a population of

agents.”

In all the theories of (1), (2), and (3), interactivities are essential, rather than derived

(there is an intrinsic relation, rather than extrinsic, relation between the parties and the

interactions as a whole). For example, Gibson´s (e.g. Gibson, 1979) affordance theory of

perception, an example of (1), the affordances (sense potentials) of objects in the

environment are realised only if there is a perceiver making situated sense of them.

Theories of category (1), without the dialogical self-other interdependencies, and with

the single organism/subject as the dependent perceiver, are the dominant way of

thinking across human sciences:

Transfer theories (monologism): inducer of reaction >> reaction

Phenomenology: Husserl, Merleau-Ponty, Thompson (2007)

Organism-environment theories, e.g. von Uexküll, Maturana, Varela, and input

from these in Thompson

Linguistic pragmatics: e.g. Benveniste, Searle, Grice etc

Interactionist neurobiology: Damasio

DLT

But let us look at things from the point of view of self-other interdependence: Is (1)

really part of dialogism? Well, there are different dialogical theories. (The exact

terminological or conceptual demarcation of `dialogism´ is not the important issue in

this context.3 But it is clear that (2) is only one part of the subject´s interaction with the

ecosocial world, part of interactionism. In my view, the core of (claassical) dialogism (2)

must be compatible with interactionism in general, i.e. (1). If dialogism only deals with

linguistic interactions between people, we run the risk of segregating language from its

contexts (cf. Harris 1997). Ecumenical dialogism (Linell, 2009) allows for both (2) and

(3), and other variants, which amounts to a special theoretical stance. (But note that DLT

is not homogeneous as a general framework either.)

In other words, interactionism (and `extended dialogism´) covers both interaction

between self´s minded body/embodied mind and others (with their minded bodies), and

its interactivities with objects (including artefacts) and processes in the ecosocial world

(which includes the cultural world with its social norms, preferences and probabilities).

From now on I will deal, in this presentation, with two points (apart from the new metatheory of language), one of which (all?) dialogists agree upon (the otherinterdependence), and one which they disagree (should we have (2) or (3) within the

framework?)

2. The other-interdependence in interaction

This point concerns the presence of others in the individual´s communication and

cognition. Recall that this applies to both direct and indirect interaction, from overt

socio-dialogue to solo thinking, silent individual reading and lone writing (the latter will

contain more of unidirectional dependencies, but they are still other-(inter)dependent

(Linell, 2009).

3

On different dialogical and dialogue theories, cf. Linell (2014c).

Here I will give only examples of the role of other-dependencies among parties to a

conversation.4

2:1: Utterances are not the context-independent products of autonomous

speakers

(#1) Reported speech and affinity between adjacent utterances: What a speaker

chooses to say at a given point of a conversation is usually heavily dependent on what

other speakers have just said. The new speaker often uses some of prior speakers´ actual

wordings. The most obvious case is probably that of reported speech, by which the

speaker directly or indirectly reports what somebody else has said. (A classical

treatment of reported speech as evidence of dialogicality is Voloshinov (1973.) But the

quoting of others´ thoughts and utterances is much more extended than just reported

speech. The new contribution is often provoked by a prior utterance and the contextual

resources actualised by that (or by the affordances of the surrounding situation).

The ”power of dialogue” to reproduce itself lies in this: A produces an utterance, which

provokes a response from B (B chooses to attend to some aspects of the linguistic and

contextual resources of A´s utterance), which in turn provokes another contribution by

A, etc. As a consequence, contributions to a sequence of interaction with two or more

participants are interlinked. There is a tendency for participants to reuse (recycle) the

others´ (and their own) words with variation (Anward, 2014); there is `resonance´ or

`affinity´ (Du Bois, 2009) between utterances. (Cf. the notion of `priming´ in

psycholinguistics.) That is, a speaker may repeat some of the other´s words, in lexicogrammatically the same or similar form but often prosodically reaccentuated (Bakhtin).

An example from Du Bois (op.cit.: 11):

(1) (Deadly Diseases SBC015) (from a psychotherapy session? CHECK!)

1. Lenore: so your mother´s happy now.

2.

(0.2)

See also Linell & Mertzlufft (2014). One may perhaps think of the three groupings

below as building on the properties of sequentiality, joint action and partial holism

(larger units of discourse than only singular ”speech acts”), respectively.

4

3. Joanne: .hh my mother´s never happy.

4.

[my mother wouldn´t be happy if] everything was g-

5. Lenore: [excuse me hhh ]

6. Joanne:

hrmm everything was great, and everything is

7.

great.

Such inter-turn links may be used to emphasise agreement and consensus, or difference

and competition (depending on co-texts and prosodies, among other things). In terms of

M. Goodwin´s (1990: 177ff.) related notion of `format tying´, the partial repetition of

others´ utterances is used mainly for competitive purposes (Goodwin is particularly

concerned ritual insults among young Black girls).

By way of conclusion, theories of interactivity tend to emphasise co-action or joint

action. The question ”Who came up with the idea?” can often not be given an individualbased answer.

[OTHER EXAMPLES : STOLEN: lines 17, 19; ; BBGun: gun, lines 9, 11, 14, 16, 20, 22;

really long one, lines 25, 27, 32, 34, 37; drama (only B) lines 48, 57, 59, 62. See

Appendices.]

#2: Responsivity and projectivity between adjacent utterances:

The affinity between adjacent utterances is a consequence of the responsivity of

utterances; an utterance is made relevant as a response to prior contributions

(responsivity). (Of course, speakers can also abruptly introduce new topics. But in such

cases the new topic is often somehow ”near at hand” in the specific situation

(encounter), or the speaker must mark it specifically as a new topic.)

We can see that utterances have external relations both to prior actions (responsive

relations) and to possible next actions (projective or anticipatory relations). However,

the relative strength of responsive and projective relations can vary. Also, responsive

and projective properties may also be built into grammatical constructions of the

language system; we may talk about `responsive´ or `projective´ constructions, and some

constructions have both these external relations at the same time. As an example of a

responsive construction, consider Swedish x-och-x (Linell & Mertzlufft, 2014):

(2) Swedish x-och-x: Transcribed from a trailer for an upcoming series (March, 2007) of

talk-shows on Swedish state television (Carin tjuett å tretti `Carin 21.30´) to be led by a

well-known journalist, Carin Hjulström; S = speaker voice, C = Carin Hjulström)

1 S: Carin tjuett å tretti (.) e tibaka.

Carin twenty-one thirty (.) is back

2 C: tibaka å tibaka ja har ju vatt här hela tiden.

back and back (i.e. `back it depewnds on what you mean´)

I have PRT been here all the time

Utterances can provide affordances (Rommetveit, 1974: `message potentials´) for

several interpretations. Here, Carin picks up, in line 2, on two opposed interpretations of

her `being back´ in the S(peaker´)s line 1, i.e. that the specific program (`Carin 21.30´)

has been off the air for some time (something which makes line 1 situationally

adequate), vs. that she (referred to as `I´ in line 2) has appeared in other programs `the

whole time´ (something which makes line 1 more situationally inadequate). Precisely

this type of partial contradiction is the special function of the grammatical construction

we call x-and-x (Linell & Mertzlufft, 2014).5

[Projective constructions: Interrogative utterances constructed in specific ways project

specific kinds of `type-conforming´ (Raymond, 2003) responses. Other examples

(Appendices): responsivity: BBGun: lines 2<1, 4<3, 6<3/4, 9<1/7, 11 and 14 counterquestions or follow-up questions to l. 9;

Projectivity: BBGun; 1>2, 3>4, 11>12 etc]

#3: The dynamics of utterance-building: Internal dialogue within single turns and

utterances: Incremental production of utterances: The preceding point has a turn- or

utterance-internal counterpart. Utterance building is done incrementally, in a step-wise

Note, however, that S(peaker) talks about the specific program (`Carin 21.30´),

whereas C(arin) talks about her own person (`I´).

5

fashion, and is therefore analysable in terms of projectivity and fulfillment (or alteration)

of projections (Linell, 2013b; Günthner, 2011).6 This can be seen as an indication of a

speaker´s `internal dialogue´; the speaker orients to different positions (or `voices´), his

own, those of the other participants and those of others not even present.

Speakers often start their turns/utterances by light beginnings, or by repeating one or a

few of the other´s central words in a prior turn/utterance (Pickering & Garrod, 2013: 1).

Light beginnings are methods to start by postponing the choice of specific consequential

words or topics, for example, by using routinised expressions, such as well, it´s…, there

are…, I´d say… Later, the incremental nature of the speaker´s utterance-building also

allows the listener to follow the speaker in her piece-by-piece production of

associations, intentions and expressions. These methods facilitate the listener´s task of

following and comprehending the evolving utterance. The speaker´s seraching for

listener support is embodied in feedback elicitation strategies (#4 below). In the

utterance-building process there are certain ”decision points” where the speaker must

choose how to continue and the listener may provide feedback or butt in, that is, these

points are simultaneously ”response points” (Linell, 1998). In between, there are

routinised (automatised) solutions.

(3) Excerpt from STOLEN (lines 11-19)

11. M:

.hhh uh; (d) oh: did yer not in on what ha:ppen´. (hh (hh) (d)

12. T:

no(h)o=

13. M:

=he´s flying.

14.

(0.2)

15. M:

en Ilene is going to meet im:. becuz the to:p wz ripped

16.

off´v iz car which is tih say someb´ddy helped th´mselfs.

17. T:

stolen.

18.

(0.4)

19. M:

stolen.=right out in front of my house.

The incremental nature of utterance building has been foregrounded in, for example,

Clark´s (1996) theory of discourse contributions, CA-inspired on-line syntax (Auer,

2005, 2009; Linell, 2013b), Dynamic Syntax (Kempson et al., 2001) (based on formal

syntax and pragmatics), and studies of incremental processing (Rieser & Schlangen,

2011) using psycholinguistic experiments, computational models, corpus studies, and

more abstract grammar-to-dialogue models (Kempson et al., op.cit.).

6

Here, Marsha first realises that Tony does not yet know what happened their son Joey.

When she has given expression to this (line 11), she hesitates (hh (hh) (d)) before

continuing, and Tony provides a confirmation at this response point (line 12). Marsha

then informs him on what happened, beginning with line 13 and then continuing with

lines 15-17. Here, Tony passes on possible response points (cf. line 14).

One may depict the general process of building an utterance by means of an abstract

schema of the following kind:7

(4) The decision process in utterance-building

Utterance:

------

--------

pre-front

front field

field

DP1

DP2

pp

--------mid field

DP3

ppppp (Utterance pp (Subject;

topic)

Verb)8

---------------end field

DP4

-------------

--- etc.

post-completion

field

DP5

DP6

p (Obligatory ppp (Extra

ppp (new

complements)

add-ons)

TCU)

A schema like this refers mainly to main clauses. Furthermore, it cannot be valid for all

languages. Languages that prefer an SOV basic constituent order are, for example,

different (verbs come later). Among SVO languages, there is a difference between

Topic+Subject First languages (like English) and V2 languages (with the finite verb

second in the clause, and thus first in the mid field). In Topic+Subject First languages ,

the grammatical subject either occurs as Topic (in the front field) or, if the fronted

constituent is not the grammatical subject, the subject comes first in the mid field. In V2

languages the finite verb is always the second constituent (irrespective of which type of

constituent occurs in the front field); the verb appears as the first part of the mid field.

p = perturbation. This schema is influenced by work by, among many others, Clark &

Clark (1977) and Schegloff (1996), and for Swedish Lindström (2008). Note that the

schema is abstract, which means that there are many language-specific details that will

not fit without accommodating the schema.

8 Here, in cases where the grammatical subject is not fronted (in the front field),

Topic+Subject First languages have the order subject followed by verb in the mid field,

whereas V2 languages have the order finite verb followed by the subject in te mid fie

7

Some English examples?

In any case, utterances involve major ”decision points” (DPs), where the speaker has to

take decisions of how to continue. At these points, there are often signs of perturbations

(p above) (non-fluencies): micro-pauses, ”filled pauses” (hesitation items: uh, ehrm, um

etc.), repetitions (e.g. ”stuttering”), restarts, ”light” lexical items (typically: function

words, discursive particles). DP1 designates the point where the speaker-to-be decides

(to try) to take the turn (signalled by gestures, inbreath, lip smacks, etc.).9 This is often

followed by particles, dislocated elements etc. in the so-called pre-front field (cf. above

on ”light beginnings”). This is followed by DP2 where the speaker decides on the first

semantically heavy constituent, the utterance topic (often the grammatical subject)

(unless of course the speaker chooses to continue a current topic, in which case a

pronominal subject may be used). This belongs to the front field, the first part of what

can (sometimes) be seen as the ”inner clause”. The next decision (DP3) deals with the

choice of the verb (unless this is postponed by language-specific rules to the end of the

inner clause, or if the language is a SOV language). The verb is often a very strategic

choice, which determines what is to be the utterance´s ”comment” part and projects

much of the following complements (constituents expressing obligatory semantic roles,

such as objects, some obligatory adverbials etc.). With some closely associated

constituents, often sentence advervials etc., the verb makes up the mid field. The

obligatory complements, which of course also have to be chosen (cf. DP4) or are

otherwise specified (by ”pre-fabrication”) make up the end field. In German, this is

closed by the so-called right brace. Usually, the inner clause is then potentially

syntactically complete, but not necessarily pragmatically. Then, at DP5 (which can be

repeated recursively) the speaker must decide on extra (non-obligatory) constituents,

which (if they occur) make up a post-completion field (Schegloff). After this, at DP6,

there is again several options: to relinquish the turn or try to keep it, by starting on new

turn-constructional units (TCUs).10

Such signals may occur even before short responses.

When projections are altered utterance-internally (as a consequence of the

incremental production and the wish to continue the turn, rather than give up

speakership), the resulting utterance as a whole often looks deviant from the viewpoint

of conventional written language grammar. I have illustrated such phenomena in a

9

10

Gaze behaviour is also part of this interplay; in the beginning of turns and some TCUs

(”turn-constructional units”), speakers tend to avoid gaze contact, while they seek this

towards the ends of TCUs and at important pieces of information (strategic content

words). However, there are considerable interpersonal (and intercultural) variations in

this – speakers look at addressees more or less, due to personality traits and cultural

belonging as well as communicative activity types – but the general pattern is there.

Thus, speakers (and addressees) use gaze to coordinate activities of production and

comprehension.

It is important to observe that listeners too are extra active at main decision points,

especially at D1 (when possibly competing for the turn) and at DP5 and DP6 (completing

the speaker´s turn or competing for next turn). They then provide feedback (#4 below),

or perhaps make attempts to take over the turn. How this interplay is realised depends

very much on whether participants are in agreement or disagreement on current topics.

2:2: Synchronisation between speaker´s activities and addresseee´s activities:

#4: Feedback elicitation and giving:

Listeners produce feedback signals (listener support items, e.g. nods, verbal-vocal

micro-feedback like mm, yeah, no (agreeing) etc.) at structurally suitable points

(”response points”) in the speaker´s utterances, usually after important referring

expressions, whole clauses etc. Blöndal (2005), who studied micro-feedback in Icelandic

conversational story-telling, found that verbal-vocal micro-feedback was anticipated by

both speaker and listener (Lu, 2014: 48). ”When the listener utters for example mhm or

ja in a place that is inappropriate according to the storyteller´s anticipation, the

storyteller sometimes begins to repeat what he or she has just said before and then

continues the story” (ibid.: 48). The speaker, it seems, needs ”proper” feedback from

couple of specialised articles, on pivot utterances (Norén & Linell, 201), and declarative

sentences initiated by a negated phrase (Linell & Norén, 2014) in Swedish.

listeners (cf. the consequences of absence of feedback in telephone conversation). Ward

& Tsukahara (2000) , who studied ”back-channel communication”, i.e. listener´s microfeedback, found that such feedback ”was often cued, encouraged, or allowed by the

speaker, for instance, by means of low pitch and rising intonation” (Lu, op.cit.: 54). Lu

concludes that speaker´s prosody and listener´s micro-feedback are correlated.

Other devices that are useful in seeking and accomplishing intersubjectivity include

appendor questions (isn´t it? etc.) (Gillespie & Cornish, 2012: 30). These ”tag questions”

are feedback-eliciting devices (practices).

[Also verbal elicitations: BBGun lines 2, 21]

#5: Repair, especially ”third turn repair”: Repair in conversation is provided in order

to save participants from upcoming misunderstandings. Of special interest is perhaps

”third turn repair” (”third position repair”, also called ”repair after next turn”; Schegloff,

1992). Here a first-positioned utterance (by A) has been responded to by a secondpositioned utterance (by B) without any (”next turn” or ”second position”) repair

initiation, but when the first speaker A, after this response from B, discovers or suspects

that B has probably misunderstood her (A´s) first-positioned utterance and therefore

initiates repair in the third turn.

In (3) we meet two sisters in their fifties, Agnes and Portia, who recently missed several

opportunities to get together (i.e.they didn´t meet though they had wanted to). The

lengthy telephone conversation, from which (3) is taken, began with a comment by

Portia about another such failure. Now, consider line 3:

(3) I´M NOT ASKING YOU TO COME DOWN (NB; Schegloff, 1992: 1306; A = Agnes and P

= Portia)

1. A:

I love it.

2.

(0.2)

3. P:

well, honey? I´ll probably see you one a´these day:s.

4. A:

oh:: God yeah,

5. P:

[uhh huh!

6. A:

[we-

7. A:

b´t I c- I jis´[couldn´t git down [there.

8.

(4s)

9. P:

I´m not asking [yuh tuh [come dow-

10. A:

11.

[Jesus.

[I mean I jis´- I didn´t have

five minutes yesterday.

It may seem that Portia´s line 3 is possibly heard as an invitation to Agnes to drop in for

a visit. Agnes excuses herself (line 7), whereupon Portia (line 9) provides a third turn

repair. In other words, a `third-positioned´ response tries to remedy what seems to be a

misunderstanding on the part of speaker B (Agnes) in her second-positioned response

to A´s (Portia) first-positioned turn (the `trouble source´). Accordingly, parties to a

dialogue (at least sometimes) strive to establish some temporal intersubjectivity, i.e.

they determine the degree to which they mutually understand each other. This is a

”dialogical” process; it takes two to communicate.

[There is another incipient opportunity for misunderstanding in STOLEN above (lines

15-19, cf. Schegloff 1992: 1301).]

#6: Collaborative completion: The ability to complete the other´s utterance:

Next speakers often build continuations of prior speaker´s utterance/turn. Sometimes,

they take over the prior speaker´s utterance before it has reached a recognisable

completion. They then indulge in other-completion (or collaborative completion):

(4) STEAM (BNC, H5G: 177-179; Howes, 2012: 77)

1. A:

all the machinery was

2. G:

[all steam]

3. A:

[operated] by steam.

(5) SIXTH FORM STUDENTS (BNC, H5D: 123-127; Howes, 2012: 76; two members of a

school staff filling in a form?)

1. K:

I´ve got a scribble behind it, oh annual report I´d get that

from

2. S:

right.

3. K:

and the total number of [sixth form students in a division.]

4. S:

[sixth form students in a division.]

right.

In other-completions, the addressee complete the first speaker´s utterances slightly

before or simultaneously with the first speaker. However, the first speaker may also

leave an open slot for the other to fill in (Koshik, 2002; Howes, 2012: invited utterance

completions). Repetitions across contributions (`resonance´; #1) and other-completion

contributes to alignment between participants; they build coalitions or `parties´ among

participating persons (Howes, 2012).

(Third-turn) repair, micro-feedback and other-completion (all examples of feedback in

a wider sense) are examples of the fact that speaker´s and listener´s activities are closer

to each other than the transmission model of communication suggests.

The fact that continuations of utterances can be anticipated, due to projection, implies

that speaker and listener can process on-line utterance building and utterance

understanding partly in parallel.11 This synchronisation enables listeners to complete a

speaker´s utterance which is still in progress (collaborative, or competitive, completion),

or they can take over the turn immediately, without any lapse at all, after the previous

speaker´s turn completion (e.g. Lerner, 2002). The similarity between speaker and

listener may also be expressed by the listener (second speaker) in an utterance that

could just as well have been said by the first speaker, as in example (6) (translated from

a Swedish original):

(6) A is trying to find his way to a certain room in the departmental building, is asking a

colleague for help:

1. A: Where is the new lab °or whatever it´s called°?

2. B: ((pointing diagonally upwards)) it is up there to the right.

3. A: it´s so difficult for me to tell the floors apart.

4. B: yeah, all of them are so alike, aren´t they.

Here, B´s line 4 is in fact an explanation for A´s difficulty ”to tell the floors apart” (line 3);

it is an account that could have been said by A. B ”takes the perspective” of A. In STOLEN

11

See Howes (2012) and references there to the parallelism between these activities.

( excerpt 3 above), T explains in line 17 what M has meant (or disambiguates what M

may have meant) in line 16 (cf. Schegloff, 1996: ”confirming the allusion” of M). Such

synchronisations imply that speaker and listener often coordinate their activities on-line

in a truly dialogical way; these activities are not purely individual or mutually

independent.

So there is parity, but of course not complete identity between the speaker´s and the

listener´s predicaments and opportunities. By being the externally active in producing

publicly observable behaviours (utterances) the speaker takes an initiative. But the

listener is also active (e.g. in preparing responses), is often following the speaker closely,

from moment to moment in the course of events.

More examples could be given. But in place of a summary, a quote from Streeck & Jordan

(2009: 93) will suffice:

”Human beings shift posture together, take turns at talk without delay or overlap, and

sometimes complete sentences in unison. Researchers who study interaction under the

microscope have long been fascinated by phenomena such as behavioral synchrony,

entrainment, and choral speaking.”

The close relation between utterance production and comprehension explains ”the

fluency of dialog” (Pickering & Garrod, 2013: Article 238: 2).

2.3: Larger units and projects:

#7: Partial holism: Integration of utterances within larger semiotic and sensemaking activities: The interaction between linguistic gestures, visual gestures and

manipulation of objects has been highlighted by, among others, Ch. Goodwin (2000,

forthc.). An example is the accompaniment of physical (bodily) movements as the

practical performance (say, counting on fingers) of a cognitive task (counting). An

anecdotal example would be a child counting on her fingers how many friends have

been invited to her upcoming party.

#8: Utterances as contributions to local communicative projects: Utterances are not

autonomous speech acts (Searle), but done in the service of communicative purposes.

They are contributions to local communicative projects (e.g. Linell, 2009).

Utterances are conditionally relevant to prior utterances. For example, a question

projects some kind of answer, within the semantic-pragmatic confines set up by its

composition. The following utterance by the other is evaluated as being a relevant

response. Even the absence of a response is assigned significance. Thus, one´s silence

may have a meaning, due to what the other has done and what the situation demands.

The single participant does not control the meaning of his own utterance or his silence.

Let us looked at one of Schegloff´s (2007) examples:

(7) STALLED (MDE, 1:7-23, telephone conversation, Schegloff, 2007: 64; M = Marsha, D = Donny)

1. D:

guess what.hh

2. M:

what.

3. D:

.hh my ca:r is sta:lled.

4.

(0.2)

5. D:

(´n)I´m up here in the Glen.

6. M:

oh::.

7.

{(0.4)}

8. D:

{ .hhh}

9. D:

a:nd.hh

10.

(0.2)

11. D:

I don´t know if it´s po:ssible, but {(.hhh)/(0.2)} see

12.

I haveta open up the ba:nk.hh

13.

(0.3)

14. D:

a:t uh: (.) in Brentwood?hh=

15. M:

=yeah:- en I know you want- (.) en I whoa- (.) en I

16.

would, but- except I´ve gotta leave in aybout five

17.

min(h)utes. [(hheh)

This whole excerpt seems to be a communicative project of implicitly asking for help, an

indirect request (cf. line 1: `guess what?´). Already pre-sequence (1-3) is announcing a

more comprehensive project, and already line 3 announces the problem (Donny´s car

has broken down). There follows a short description of a difficult predicament (3-5).

Lines 9-14 describes the consequences of the accident for Donny. But Marsha is unable

to help and declines (lines 15-19), a declination which comes late and is only half-way

explicit. Donny does not get what he was asking for in his communicative project.

#9: Grammar and communicative genres/activity types (act–activity

interdependence):

The deployment of linguistic resources (lexical items, grammatical constructions) is

subject to activity-grammar interdependence: constructions, as entrenched patterns of

languaging, are characterised not only by their grammatical structures and local

pragmatic functions but also by their links to larger sequences and contexts,

communicative projects, communicative activity types (Linell, 2010) and communicative

genres (Günthner & Knoblauch, 1995). Such genres and activity types involve activities

with several moves, often by different participants. Indeed, they are socioculturally

defined, and call up patterns with a social history (Cowley, 2011: 195), which the

participants in situ can conform to or deviate fram (both of which will be consequential

for the ensuing responses).

Dialogical proposals would claim that utterances invoke contexts, and contexts shape

utterances (contexts are both shaping and renewed, ”double contextuality” (Heritage,

1984); discourse and context, expression and content, are mutually constitutive. Such

analytic reasonings are condemned by monologists as circular, but they are natural

since participants can operate on several time-scales, situated moment and activityprescribed practice (”double dialogicality”; Linell, 2009; 2014d). Such facts point to the

fact that participants in situ often orient to practices shaped by (generations of)

”predecessors” (Goodwin, forthc.; cf. peripheral others), who developed and established

communicative genres and activity types.

3. Interactivities in classical and extended dialogisms

Languaging involves participants´ actions and interactions, and their decisions taken at

various points within these activities. How then have the language sciences, especially

linguistics, accounted for this agency of participants? In a recent paper (Linell, 2014b) I

discussed different competing theories of language and languaging in relation to their

assumptions about participants´ agencies in ordinary situated languaging. We can

summarise these assumptions in Table 1:

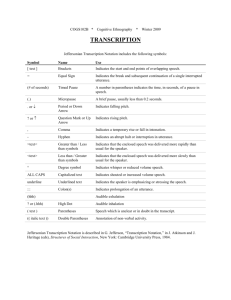

Table 1.

Primary units and forces

1: Impersonal abstract

system

2: Impersonal brain

mechanisms

3: Utterance types in

language system

4: Situated utterances

5: Situated utterances in

sequences

6: Organism–environment

system (interbodily

dynamics)

Range of individual

decision-making

No theory (limited

agency?)

No theory (very peripheral

agency?)

Some: references, lexical

items, speech act types

Vast: as above (3), plus

(intended) indirect

meanings, implicatures

Decisions at selected

points, shared agency; also

automation

Some?

Examples of traditions

Saussurean structuralism

(Later Chomskyan)

generativism

Traditional grammar (?)

Some theories in linguistic

pragmatics

Enunciation theory

Dialogism

Distributed Language

Theory

Most of phenomenology

Interactional neurobiology

Here (1-2) are actually structuralist theories of language, and they do not have any

explicit theory of languaging. For example, Chomsky (2) has nothing to say about

languaging (in his early terminology: ”performance”). No explicit theory of situated

decision-making is formulated. Nonetheless, it is implicitly clear that the impersonal

systems or mechanisms are decisive, with very little space left for the individual speaker

to decide.

Agency is assigned to participants only in (3-5). In (3), here (for want of a better

characterisation) ascribed to ”traditional grammar”, linguistic units are seen as

utterance types. Despite what we now know about the non-sententially shaped

utterances in informal talk, the utterance units are still assumed to be mostly ”wellformed sentences”. However, since sentences are taken to be utterances, there is still an

opening for some individual decision-making, concerning reference, word choice and

speech act choice.

In the next variant (4) we find the emphasis on individual agency; the speaker alone is

the agent, while the recipients are at best subordinated. This is the clearest example of

intentionalism. Within this category, I would classify Searle´s speech act theory and

Grice´s theory of implicatures and his theory of sentence meaning vs. speaker´s meaning,

as well as the enunciation theory by Benveniste (1966, 1972) and others. These, and

many other contributions to linguistic pragmatics, take the speaker´s meaning-making

into account, but the theories are mainly individualistic in nature.

If we assume that individuals cannot exercise their agency independently of others in

the interaction, we must adopt a theory of limited ”participatory agency”. This is the

position of dialogism (5), which assumes that participants in communicative and

cognitive activities are human beings with agency (Linell, 2009; Bertau, 2011), but here

the agency and sense-making are shared, or better: partially shared, not only between

speaker and addressee but also with peripheral others (”third parties”; Linell, 2009).

Human agency is not exercised as an unconstrained power to carry out any kind of

action at one´s discretion independently of context. Rather, we are concerned with an

ability to act in contexts that set up physical and social boundaries. We may talk about

this as `participatory agency´, and it has to be ”limited” in various ways, within the

”wiggle-room” of participants in particular social situations. For example, with regard to

actual languaging and utterance-building, active individual agency could only account

for some aspects of the interaction. Therefore, theories that assume languaging to be

primary with respect to the language system, e.g. dialogist theories, run the risk of

assigning too much importance to the agency and decision-making of the participants

involved. In fact, many properties of our utterances, and responses to utterances ”come

to us” in increments (Linell, 2013b, and references above; cf. the schema (4) above) from

elsewhere; for example, many ideas, attitudes, opinions and understandings ”speak

through us”, rather than being freely chosen and expressed by us in each situated speech

situation. Other limiting factors are natural biologically induced predispositions (e.g.

articulatory movements are constrained by limitations (inertia) of the speech

apparatus), the subordination to strong cultural norms (e.g. taboo), automatisation of

socioculturally acquired patterns (automatised behavioural movements, sedimented as

patterns in spoken dialects), and improvisation (Breyer et al., 2011) or pure chance

(Streeck et al., 2011). In addition, we are interdependent with others´ actions, which

means that to a considerable extent we rely on their agency rather than exclusively on

our own. Yet, there is also decision-making and responsibility on the part of speakers

(and other participants), especially at certain ”decision points”, e.g. in utterance-building

(see (3) and discussion there). All in all, this provides a picture of a mix of stepwise

emerging intentions (Rieser & Schlangen, 2011: 7) and automatised (”mechanistic”)

parts (Pickering & Garrod, 2004).

We must therefore admit that the agencies are limited or circumscribed (section 6).

Speakers act in situated linguistic practices, in which they are languaging together with

others. Thus, the speaker´s own agency, her ability to decide on utterances, is partly

overridden by social interdependencies (the fact that we are faced with ”co-actions”,

rather than independent actions by autonomous individuals). In addition, large parts

can be, and are in fact, projected (Auer, 2005, 2009) and automatised, that is, while the

speaker can decide on some crucial points (in particular, ”decision points”, as in (4)),

many other properties of the utterance will follow automatically from routinised habits

of languaging (provided that the speaker is at ease and knows her language well). And

provided that she does not try to stop her fluency and inhibit the tendency to say what

can be culturally expected.

Present-day dialogism includes the account of utterances as embodied. Mentalism, and

assumptions of immaterial souls and spirits, agency, consciousness or abstract signs,

have increasingly come under attack. The necessary focus on interactivities (e.g. Linell,

2014a) has led to the recognition of intercorporeality (Streeck & Jordan, 2009; Csordas,

2008); we interact through our bodies (cf. Hoffmeyer, 2008) and thereby we are part of

the world. This idea of intercorporeality comes largely from the work of the French

dissenting phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1962,1964). This is (6) in Table 1.

Sometimes, people connect the ideas of intercorporeality to the term ”posthumanism”.

However, this term seems to cover several rather different theories. One of them

concerns the application of organism-environment theories (Maturana & Varela,

Hoffmeyer, Steffensen) to human interaction. We may feel that we are free, responsible

and conscious agents, but this is, according to this view, largely an illusion; we can have

feelings of agency, consciousness and thinking (Harnad, 2005), but this is presumably

just epiphenomena, not causally involved forces. We do not act by ourselves; languaging

is not actions, but rather ”events that just happen to us”. Thus, humanism would ascribe

something characteristically ”human” to people only on erroneous grounds; we are

simply subjected to interbodily dynamics, just like other animals.

Accordingly, in the discussions of bodies in interaction, there are currently partially nondialogist variants of interactivity (”intercorporeality”; Streeck & Jordan, 2009) that

apparently tend to minimise agency, sometimes even deny it. Organism-environment

theories (6) tend to look at the interaction between organism and environment, without

really assigning any role for sociodialogue (interaction between self and other) (Linell,

2013a). A majority of them seem to deny the partial uniqueness of self-other interaction,

and accordingly they focus on the interactivities of the single sense-maker (seen as

organism, self, perceiver, body) and the environment. As mentioned above (section 1),

DLT shares this attitude with several other – theoretically often quite different –

paradigms, such as linguistic pragmatics, phenomenology Maturana/Varela type of

biogenic theory, Donald´s theory of the co-evolution of the embodied mind and the

external culture, interactional neurobiology, etc. In other words, these theories (6)

support a view of languaging that goes against classical dialogism, in which symbols

(words), actions, meanings and accountabilities remain central.

Dialogism is centred around self-other interactivities; this is something which can not be

dispensed with, and the meta-theory then comes out as part of a tradition of humanities.

But many dialogists are also interested in self-environment interactivities, e.g. as

regards sensory perception (e.g. Linell, 2009: 415ff.), and they certainly acknowledge

the embodied nature of languaging. But from this dialogist point-of-view (cf. (5) in Table

1), the interacting bodies are minded bodies, not just (living) physical or biological

organisms. It seems reasonable to argue that the values, in particular, the situated

meanings created in human interactions and civilisations, are not so ”immaterial”,

”mental” or ”spiritual” as we have been told before, but instead part of material

processes. But we still ascribe semiotic affordances, meaning potentials, to the material

objects and processes involved in human meaning-making, and behind these potentials

are minded people. In Cowley´s (2011b) words (following Rączaszek-Leonardi, 2011),

language (languaging) is both ”dynamic” (interbodily) and ”symbolic”.12 We may add

that language is not only dynamical, material and situated, but it is also meaningful,

symbolically and historically constituted, concerned and moral (Putnam, 1978;

Rommetveit, 1991) etc. Having a mind is to have a sense-making ability, and this is what

created the human ecological niche, what makes us human. Language offers

opportunities to reflect on language itself, especially in literate cultures, and therefore it

provides a capacity to use language reflexibly, intentionally and accountably. Our

civilisation builds upon the assumption that we can hold people legally and morally

accountable for their doings.

Accordingly, dialogical theories cannot accept a total elimination of agency and

consciousness. But it seems undeniable that agency and consciousness do not have an

entirely sovereign status in the explanation of human behaviour, including

communication and cognition. We can not claim that languaging always involve a lot of

conscious decision-makings ”at all points”. We need a theory of ”limited agency” (section

6).13 The ideas of intercorporeality in DLT and elsewhere may have something to

contribute here.

Finally, it should be pointed out that the foci on interbodily dynamics vs. accountable

meaning-making may concern different aspects of multimodal languaging. There are

plenty of mirroring behaviours in postures, touch (e.g. hugging), facial expressions,

gestures, in some prosodies, and to some extent in the choice of similar vocabularies and

even grammatical constructions (cf. #1 in section 4) (Mehrabian, 1972). These mutual

mirrorings, which belong largely to the extra- and para-verbal aspects of languaging, do

of course embodily a lot of other-interdependence, and in that sense plenty of

I assume that Cowley and Rączaszek-Leonardi would not necessarily call themselves

posthumanists.

13 In addition, many neurobiologists also hold on to the need of a ”central planner” in

their theories of the brain (cf. discussion in Donald, 2008).

12

dialogicality and interactivity. They provide for some kinds of shared sense-making or

even communion, aspects which are shown rather than said. On the other hand, we have

the verbal (more strictly language-related) aspects of languaging that involve more of

conscious meaning-making, obligations of accountability and, arguably, agency too.

These are rather different aspects of dialogicality and intersubjectivity. So, the theories

of accountable meaning-making and intercorporeality may after all be compatible. On

the one hand, languaging involves automation and nonconsciousness, on the other

interbodily dynamics sustains actions and meanings.

4. The new language theory

If we wish to focus on language and languaging, we will find that a new collection of

theoretical assumptions now havet o be adopted, assumptions that go against the

theoretical foundations of most ”modern” approaches to language within linguistics and

also other language sciences. (Thus, if these points may seem well-established to the

present audience, they remain highly controversial in the discipline of linguistics.) Here

is a non-exhaustive list:

(i) Languaging is prior to language, and languaging is not just about the application of a

language system. Situated actions are primordial, rather than derivative.

(ii) Utterances are embodied (we can talk about an embodied mind (ability to make

sense) and a minded body), multi-modal, temporally distributed and socioculturally and

situationally embedded actions, rather than sequences of abstract forms. (Written

language is a different matter.)

(iii) Language/ing developed out of other partly pre-existing semiotic resources, in

phylogenesis as well as ontogenesis and sociohistorical genesis (Trevarthen, Donald,

Tomasello). This is of course not to deny that once people have mastered verbal

language in their spoken interaction and in writing, their language can reflexively

influence their cognitive and communicative achievements.

(iv) Language itself is not entirely sovereign in sense-making; it cannot express

everything.

(v) Other people are always directly or indirectly present in our sense-makings (cf.

above on the other-interdependence).

(vi) Interactivities are prior to intersubjectivities. Language is individual and collective

at the same time, and it is based on interactivities (social interactions between

individuals who are themselves social beings) (Linell, 2014a).

(vii) Participants in normal situated languaging can execute their own agency, but only

in limited ways.

(viii) Utterances in real, situated languaging only sometimes exhibit the forms of clauses

and sentences (as these have been described in sentence grammars). Many utterances

consists of ”fragments” and self-standing phrases (cf. ”prefabricated phrases”, ”ellipsis”;

Laury, 2008), grammatically inconsistent structures (e.g. pivot utterances; Norén &

Linell, 2013), etc. Grammatical processes in languaging cannot be adequately captured

in static (structuralist or generativist) models, but require a dynamic, temporally based

”on-line syntax” (Auer, 2005, 2009).

(ix) Like other levels of languaging, the phonetics of the vocal-tract behaviours requires

an action account. Oral-vocal language/languaging is about producing hearable sounds.

But the phonological unis are not abstract segment types, but phonetic events, or

articulatory gestures defined in terms of target values for their acoustic results (e.g.

Fowler, 1986).

(x) The situated meanings of utterances are always dependent on an interplay between

meaning potentials of linguistic resources (lexical items and grammatical constructions)

and contextual resources of various kinds. Even if we abstract utterance types

(”linguistic sentences”), their ”linguistic” or ”semantic” meanings can not be derived by

principles of compositionality (Linell, 2013b).

(xi) Traditional and modern linguistics have been subject to a Written Language Bias

(Linell, 2005), and dialogism perhaps to a Language Bias (Linell, 2009). It is not selfevident that (within a specific ”language”, such as English) interactional, oral languaging

and literate texts have the same underlying grammar.

(xii) Structuralism in both Europe and America has been limited in its explanatory

power: it started with idealised fully competent users´ systems, rather than with a

developmental perspective.

References:

Auer, Peter. 2005. Projection in interaction and projection in grammar. Text, 25: 7-36.

Auer, Peter. 2009. On-line syntax: Thoughts on the temporality of spoken language. Language Sciences, 31:

1-13.

Bakhtin, Mikhail. 1986. The Problem of Speech Genres. In: Bakhtin, M., Speech Genres and Other Late

Essays. Translated by V.W. McGee. Texas: University of Texas Press. 159-172.

Barresi, John & Moore, Chris. 2008. The neuroscience of social understanding. In Zlatev et al. (2008). 39‐

66.

Becker, A. L. 1991. Language and Languaging. Language & Communication, 11: 33-35.

Benveniste, Emile. 1966 and 1972. Problèmes de linguistique générale, Vols. 1 (1966) and 2 (1974). Paris:

Gallimard.

Bertau, Marie-Cécile. 2011.

Blöndal, P. 2005. Feedback in conversational storytelling. In: Allwood, J. (ed.), Feedback in Spoken

Interaction – Nordtalk Symposium 2013. (Gothenburg Papers in Theoretical Linguistics, 91). Göteborg

University: Department of Linguistics. 1-17.

Breyer, Thiemo, Ehmer, Oliver & Pfänder, Stefan. 2011. Improvisation, temporality and emergent

constructions. In: Auer, P. & Pfänder, S. (eds.), Constructions: Emerging and emergent. Berlin: De Gruyter.

218-162.

Clark, Herbert H. 1996. Using Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cowley, Stephen. 2011. (ed.), Distributed Language. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Cowley, Stephen, Major, João, Steffensen, Sune V. & Dinis, Alfredo. 2010. (eds.), Signifying Bodies:

Biosemiosis, Interaction and Health. Braga: The Faculty of Philosophy of Braga.

Damasio, Antonio. 1994. Descartes´ Error: Emotion, reason and the human brain. New York: Macmillan.

Damasio, Antonio. 2000. The Feeling of What Happens: Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness.

London: Vintage Books.

Donald, Merlin. 2008. How culture and brain mechanisms interact in decision making. In: Engel, C. &

Singer, W. (eds.), Better than Conscious? Decision Making, the Human Mind, and Implications for

Institutions. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. 191-205.

Du Bois, John. 2009. Towards a Dialogic Syntax. Ms. available at dubois@linguistics.ucsb.edu

Fowler, Carol. 1986. An event approach to the study of speech perception from a direct-realist

perspective. Journal of Phonetics, 14: 3-28.

Gibson, James. 1979. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. Boston: Houghton-Mifflin.

Gillespie, Alex & Cornish, Flora. 2009. Intersubjectivity: Towards a Dialogical Analysis. Journal for the

Theory of Social Behaviour, 40: 19-46.

Goodwin, Charles. 2000. Action and embodiment within situated human interaction. Journal of Pragmatics,

32: 1489-1522.

Goodwin, Charles. Forthcoming book.

Goodwin, Charles, Streeck, Jürgen & LeBaron, Curtis. 2011.

Günthner, Susanne. 2005. Dichte Konstruktionen. InLiSt 43. http://www.unipotsdam.de/u/ynlist/issues/43/index.htm

Harris, Roy. 1997. From an integrational point of view. In G. Wolf & N. Love (eds.), Linguistics Inside out:

Roy Harris and his critics. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. 229-310.

Haye, Andrés & Larraín, Antonia. 2012. What is an Utterance? In: Märtsin, M. et al., (eds.), Dialogicality in

Focus. New York: Nova Science Publishers. 33-52.

Hoffmeyer, Jesper. 2008. The Semiotic Body. Biosemiotics, 1: 169-190.

Howes, Christine. 2012. Coordinating in Dialogue: Using compound contributions to join a party. Ph. D.

diss. Queen Mary University of London.

Kempson, Ruth, Meyer-Viol, Wilfried & Gabbay, Dov. 2001. Dynamic Syntax: The Flow of Language.

London: Blackwell.

Koshik, Irene. 2002. Designedly Incomplete Utterances: A pedagogical practice for elicting knowledge

displays in error correction sequences. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 35: 277-309.

Laury, Ritva. 2008. (ed.). Crosslinguistic Studies of Clause Combining: the Multifunctionality of Conjunctions.

Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Lerner, Gene. 2002. Turn-Sharing: The choral co-production of talk-in-interaction. In: Ford, C., Fox, B. &

Thompson, S.A. (eds.), The Language of Turn and Sequence. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 225-256.

Lindström, Jan. 2008. Tur och ordning: Introduktion till svensk samtalsgrammatik. Stockholm: Norstedts

Akademiska Förlag.

Linell, Per. 2009. Rethinking Language, Mind and World: Interactional and contextual theories of human

sense-making. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Linell, Per. 2013a. Distributed Language Theory, with or without dialogue? Language Sciences, 40: 168173.

Linell, Per. 2013b. The Dynamics of Incrementation in Utterance-Building: Processes and resources. In:

Szczepek Reed, B. & Raymond, G. (eds.), Units of Talk – Units of Actions. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. 5789.

Linell, Per. 2013c. Are natural languages codes? PERILUS 2011, Symposium on Language Acquistition and

Language Evolution. (Stockholm University: Department o Linguistics). 39-50.

Linell, Per. 2014a. Interactivities, intersubjectivities and language: On dialogism and phenomenology.

Forthc. in Language and Dialogue, 4:2.

Linell, Per. 2014b. Dialogical theories and participants´ agency in situated interaction. Ms.

Linell, Per. 2014c. Dialogue theories vs. dialogical theories. Ms.

Linell, Per. 2014d/forthc. Mishearings: Pragmatics and situations first, language and linguistic analysis

afterwards. Ms.

Linell, Per & Mertzlufft, Christine. 2014. Evidence for a Dialogical Grammar: Reactive constructions in

Swedish and German. Forthc. in: Günthner, S. (ed.), Grammar and Dialogism: Sequential, syntactic and

prosodic patterns between emergence and sedimentation. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Linell, Per & Norén, Kerstin. 2014. ”Nä inte från början ä dom inte de” – inte + XP som fundament i

satsformade yttranden. Forthc. in Festschrift for NN.

Lu, Jia. 2014. Modality and prosody of micro-feedback in relation to understanding in intercultural

communication: First encounters between Swedes and Chinese. Gothenburg, SE: Department of Applied

Information Technology.

MacNeilage, Peter. 2008. The Origin of Speech. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Marková, Ivana. 2003. Dialogicality and Social Representations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Maturana, H.R. & Varela, F.J. 1980. The Tree of Knowledge: The Biological Roots of Human Understanding.

Boston: New Science Library.

Mehrabian, Albert. 1972. Nonverbal Communication. Chicago: Aldine-Atherton.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. 1964. The Visible and the Invisible. Transl. by A. Lingis. Evanston: Northwestern

University Press.

Norén, Niklas & Linell, Per. 2013. Pivot constructions as everyday conversational phenomena within a

cross-linguistic perspective: An introduction. Journal of Linguistics, 54: 1-15.

Olson, David. 1994. The World on Paper: The conceptual and cognitive implications of writing and reading.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pickering, Martin & Garrod, Simon. 2004. Toward a mechanistic psychology of dialogue. Behavioral and

Brain Sciences, 27: 169-226.

Pickering, Martin & Garrod, Simon. 2013. How tightly are production and comprehension interwoven?

Frontiers in Psychology, 4: Article 238 (April 2013).

Putnam, Hilary. 1978. Meaning and the Moral Sciences. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Rączaszek-Leonardi, Joanna. 2011. Symbols as constraints: the structuring role of dynamics and selforganization in natural language. In Cowley (2011a): 161-184.

Raymond, Geoffrey. 2003. Grammar and social organization: Yes/no interrogatives and the structure of

responding. American Sociological Review, 68: 939-967.

Rieser, Hannes & Schlangen, David. 2011. Introduction to the Special Issue on Incremental Processing in

Dialogue. Dialogue & Discourse, 2: 1-10.

Rommetveit, Ragnar. 1974. On Message Structure. London: Wiley.

Rommetveit, Ragnar. 1991. On epistemic responsibility in human communication. In: Rönning, H. &

Lundby, K. (eds.), Media and Communication. Readings in Methodology, History and Culture. Oslo:

Norwegian University Press. 13-27.

Schegloff, Emanuel A. 1992. Repair after Next Turn: The last structurally provided defense of

intersubjectivity in conversation. American Journal of Sociology, 97: 1295-1345.

Schegloff, Emanuel A. 1997. Third Turn Repair. In: Guy, G., Feagin, C., Schiffrin, D. & Baugh, J. (eds.),

Towards a Social Scence of Language 2. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. 31-39.

Streeck, Jü rgen, Goodwin, Charles & LeBaron, Curtis. 2011. (eds.), Embodied Interaction. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Streeck, Jürgen & Jordan, Scott. 2009. Projection and Anticipation: The forward-looking nature of

embodied communication. Discourse Processes, 46: 93-102.

Thibault, Paul. 2011. First order languaging dynamics and second‐order language: the distributed

language view. Ecological Psychology, 23: 210‐245.

Thompson, Evan. 2007. Mind in Life: Biology, phenomenology, and the sciences of mind. Cambridge, MA:

Belknap Press.

Ward, N. & Tsukahara, W. 2000. Prosodic features which cue back-channel responses in English and

Japanese. Journal of Pragmatics, 32: 1177-1207.

Zlatev, Jordan, Racine, Timothy, Sinha, Chris & Itkonen, Esa. 2008a. (eds.). The Shared Mind: Perspectives

on intersubjectivity. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.