The Grammar of Storytelling ()

advertisement

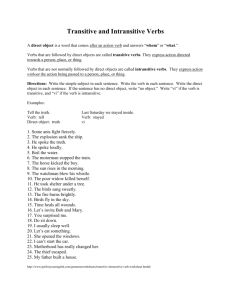

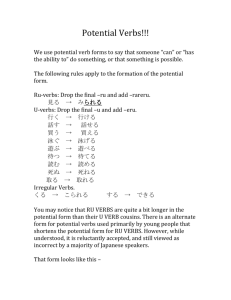

The Grammar of Storytelling David Hann uncovers the way we use grammar as a ‘dynamic and strategic weapon’, and analyses an extract from Cormac McCarthy’s The Crossing. We tell stories every day. I don’t mean by this that we sit around a winter’s fire as our ancestors must have done and recount tales of fantastical events and weird and wonderful happenings. But we all tell stories nonetheless. Just think of coming home from school, college or work. A member of the family enquires ‘How was your day?’ Maybe you just shrug your shoulders and say ‘OK’ or perhaps an amusing or annoying event comes to mind which you then recount. And so you tell a story. But, you might argue, the word story suggests something created rather than something about the real world. I would counter that your anecdote is created. I’m not accusing you of lying or fantasising. The event you recount is not a figment of your imagination. However, it would be impossible for you to relate it without adding your own creative input. Consciously or not, you inevitably present events and characters in a particular light, in such a way as to influence how they are received by your listening audience. This article seeks to explore the tools we use to do this. Of course, vocabulary, with the emotional baggage it can carry, is one means by which you might influence how events are seen. However, I am going to concentrate on an aspect of language which, on first sight, might simply seem to function as the cement that we use to put our words together – grammar, and more specifically on verbs, sometimes misleadingly called ‘doing words’. I am not going to look so much at the meanings they carry, although these are important. (Think, for example, of the different impressions created by the verbs swagger and walk.) I am simply going to look at their grammatical behaviour and how different grammatical verb-types (called processes in this article) influence perceptions of the events and characters that they describe. Using Grammar Strategically Imagine a simple scenario: you find yourself helping out at a child’s birthday party. The party’s entered its final stages and you are in the process of organising a little game to keep the children occupied till their parents arrive to pick them up. Suddenly, you hear an almighty crashing sound from another room. You rush towards the noise, expecting the worst. As you enter the room, you see before you a little boy, broken china at his feet. He colours with embarrassment but is otherwise unhurt. ‘What happened?’ you ask unnecessarily. ‘The plate broke’, he says sheepishly. Although it may not be the first thought that enters your head in a situation like this, what this episode illustrates is that, as soon as we start acquiring our native tongue, we also learn how to use its grammar strategically, especially when we tell stories about events. In this case, the little boy might have said, ‘I broke the plate’. You can probably understand why he decided against this. Nevertheless, it is worth exploring the options open to him in a bit more depth as this will throw some light on different process-types and how we exploit them. ‘I broke the plate’ is a sentence which is congruent with reality. It reflects what happened. Technically, it has an agent ‘I’, an action ‘broke’ and the object affected by the action, ‘the plate’. To give you another technical term which you may already know, the verb ‘broke’ here is transitive which means that it has a direct object. If you look in your dictionary, you will see that verbs can be transitive or intransitive. The latter do not have an object (for example, ‘he fell down’). For obvious reasons, the boy doesn’t want to present himself as the agent of the mishap. One option open to him would have been to use the passive voice ‘the plate has been broken’ which allows him to ditch the agent ‘by me’. Although linguistically impressive coming from a five-year-old, this could have invited the question ‘Who by?’ (or, if you are feeling pedantic, ‘By whom?’). However, fortunately for the little boy, the verb ‘break’ is quite nifty because it can be either transitive or intransitive (you could use the term ergative to describe such a verb if you want to impress your friends – or lose them!). You could argue that, regardless of his use of the ergative verb, the little boy is still in a difficult spot. It is obvious that the plate did not break itself (although, interestingly, this is exactly how the grammar presents it). If you imagined that only a naïve five-year-old can use such a strategy, a more grown-up scenario should dispel such an idea: the CEO of a company tells the waiting media at a press conference about the ‘rationalisations’ they are having to make. ‘Regretfully, the Birmingham factory will have to close’, he says. Again, if we think about this sentence, it is literally absurd (the factory doesn’t prepare to shut and padlock its own gates). Yet this sentence sounds unremarkable in this particular context. Before we investigate the strategic use of verbs further, we need some additional categories to help us with our analysis. Halliday’s Categories Michael Halliday, an influential British linguist, believes that our grammar is shaped by what we use it to do. It was he who came up with the categories I’m about to give you. A verb like ‘break’ is what he calls a material process, involving a physical activity. As we have already seen, this process can involve an agent (someone or something which performs the action) and an affected (someone or something which is affected by the action). You’ve probably already realised that not all verbs are physical/material processes. So, here are the other main categories: Mental processes are realised by verbs like know, want, love, understand. As you can see, these involve the verbs of head and heart (cognition and emotion). Here are a couple of examples: He likes her. He couldn’t grasp the gist of her message. Verbal processes are related to communication and can be realised by verbs such as ‘talk’, ‘speak’, ‘enquire’ but also ‘write’, ‘text’ and so on: I told him what to do. She texted the details to him. Finally, we have relational processes. These describe an attribute of something or someone, and actually don’t seem like processes at all. Because they involve an attribute, the verb is usually followed by an adjective: She is angry. He looks strange. The above doesn’t do justice to the complexity of Halliday’s analytical framework but it is enough for our present purposes. An Example Now, let us turn to an example of strategic language use from the recent past. If you follow politics, you may remember that in October 2011, Liam Fox, who was then Foreign Secretary, had to resign his post because it was deemed that he had allowed a personal friend political access and influence that was inappropriate. He stood up in the House of Commons and made a statement about what had happened and his reasons for resigning. In other words, he told a story. Here is a short but significant extract from that speech with the verbs I want to focus on in italics: The ministerial code had been found to be breached and for this I am sorry. I accept that it is not only the substance but perception that matters and that is why I chose to resign. I accept the consequences for me without bitterness or rancour. • Can you categorise the italicised verbs in terms of process types? • Which significant material process does Liam Fox decide not to make himself the agent of? • Does he apologise? Most of the verbs are material processes except for a couple (more on these below). Of course, the material process for which he doesn’t make himself the agent is the verb ‘breach’. Much as the little boy doesn’t say ‘I broke the plate’ or the CEO ‘We are closing the factory’, Fox doesn’t say ‘I breached the ministerial code’. He does, however, make himself the dynamic agent of choosing to resign and accepting the consequences. There are some other strategic uses of language beyond the verbs here which you may wish to reflect upon in your own time. Fox chooses the relational phrase ‘I am sorry’, rather than opting for the verbal ‘I apologise’. To me, the two feel quite different. The adjective sorry carries various possible meanings, including that of simply being sad. Apologise, on the other hand, is a dynamic verb of repentance. ‘Typical politician!’ you might think. However, we shouldn’t be too hard on Mr Fox as we are all strategic manipulators of the language. Analysing Literature Finally, I would like to look at a short extract of fiction with you to show that process types can be a useful tool in analysing literature. The following is from the novel The Crossing by the American writer, Cormac McCarthy. Most of his work is set in ‘cowboy’ country. This particular story centres on a teenager, Billy. He and his family attempt to catch a wolf which has been harassing and killing cattle in their area. They have laid various traps for the animal and, in this section, Billy comes across the trapped wolf for the first time. I have put in italics those verbs which primarily relate to him: He rode past the old dance platform in the woods, and two hours later when he left the road and crossed the pasture to the vaqueros’ noon fire the wolf stood up to meet him. The horse stopped and backed and stamped. He held the animal and patted it and watched the wolf. His heart was slamming inside his chest like something that wanted out. She was caught by the right forefoot. The drag had caught in a cholla less than a hundred feet from the fire and there she stood. He patted the horse and spoke to it and reached down and unfastened the buckle on the saddlescabbard and slid the rifle free and stepped down and dropped the reins. The wolf crouched slightly. As if she’d try to hide. Then she stood again and looked at him and looked off towards the mountains. • What is your first impression of the boy on first reading this? • Which process type predominates here? • Which process types might you expect to find in this extract which are not, in fact, present? • How do we know about the boy’s fear? What do you notice about how it is presented in terms of process types? On first reading the section, it struck me that young Billy demonstrates a cool presence of mind. This impression is created primarily by McCarthy’s choice of process types. Material action predominates, involving the use of primarily transitive verbs, as Billy takes control of the situation. We only learn of his fear through a description of his body’s reaction (notice how his heart is an agent for the material process of hammering). We have no relational or mental processes here as we might expect (think of how you would describe this event if it had happened to you!). It is as if Billy has divorced himself from his own emotions in order to act effectively. Notice too how the first mention of the wolf does not include a description of Billy’s reaction on first seeing her. This seems to be a world where, in order to survive, action is paramount and emotion must be held in check. I hope that this brief exploration of verbs has shown that grammar is not just a set of rules which we either abide by or not, but is, in fact, a dynamic and strategic weapon which we all employ. Whether we are creating a fictional world in a novel or recreating the happenings in our daily lives, we make grammatical choices which profoundly affect how characters and events are presented and perceived. David Hann is a Lecturer at the Open University in Literature and Linguistics. This article first appeared in emagazine 56, April 2012.